Author : Irina Mamulashvili

The European Council took a historic decision on 24 June 2022. It granted Ukraine and Moldova European Union Candidate Status and Georgia the European Perspective. This means that the country will receive candidate status only after it fulfils 12 recommendations set by the EU. Among these priorities are the elimination of polarisation, improvement of the electoral system, judicial reform, fight against corruption, de-oligarchisation, fight against organised crime, ensuring media freedom, protection of the rights of vulnerable groups, promotion of gender equality, enhancing civil society participation, protection of human rights, and election of an independent public defender.

The year of 2023 will be a turning point in the EU-Georgia relationship, as a decision will be made at the end of this year on whether the country will be granted EU Candidate Status. Such a window of opportunity is rare, as it usually opens only because of significant geopolitical shifts. It was Russia’s large-scale attack on Ukraine and the terrible consequences that followed that forced a rethinking of security issues in the EU and made the issue of its eastward enlargement relevant. For Georgia, this is a crucial opportunity for becoming part of the EU enlargement process, a goal it has waited for so long and travelled such a long way to achieve.

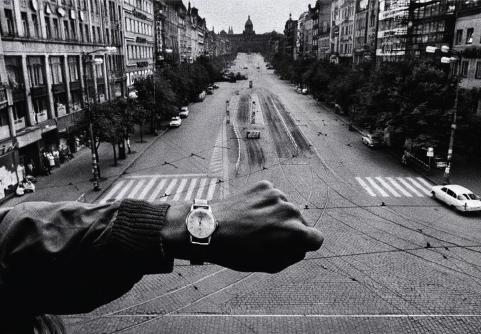

For hundreds of years, Georgia has been an arena for clashes and conflicts between empires and cultures. This was largely due to its geographical location at the crossroads of two worlds – East and West – which gave it cultural richness, a strategic position for trade and unique opportunities for transit. Its location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia made it a battleground for the influence of various states. However, European values were so deeply rooted in Georgia that this identity and sense of belonging to the Western world never faded.

Christianity played a significant role in the formation of Georgia’s European identity. However, at the same time, it was Orthodoxy that proved to be the decisive factor, which, against the background of the attacks of Islamic countries, showed the then rulers of the country a need to strengthen Georgia’s ties with Russia, thus alienating it from Europe. During Georgia’s brief period of independence in 1917-1921, the notion of a “return to Europe” emerged. However, Russia’s conquest of Georgia isolated the country and separated it from Europe for many decades.

Since the restoration of independence, despite foreign policy fluctuations and internal turmoil, Georgia has expressed its desire to join Euro-Atlantic structures. This process became evident when Georgia joined the Council of Europe in 1999. It was here that Zurab Zhvania made his historic speech: “I am a Georgian, therefore I am a European”.

The process of Georgia’s integration into Euro-Atlantic institutions intensified further after the 2003 Rose Revolution, when a period of economic and political reforms began and the country’s accession to the European Union and NATO was named among the main priorities of its foreign policy. In addition to intensified efforts towards European integration, attention was paid to the dissemination of EU symbols throughout the country, such as the use of EU flags, which were often placed next to the Georgian flag, aimed at strengthening the sense of belonging to Europe in Georgian society.

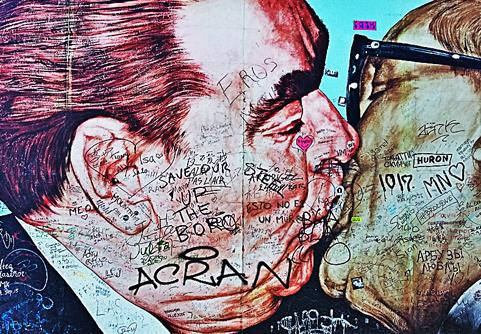

Shortly after the Rose Revolution, significant changes took place on the European continent. The European Union began to expand on its eastern flank in 2004 and 2007, reducing the borders between Georgia and the EU countries and extending the EU to the Black Sea. These developments had a significant impact on Georgia-EU relations, as the country became part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP). Although this framework of relations did not involve ambitious proposals to Georgia, the issue was important in terms of recognition of the country. In particular, ENP membership gave Georgia, which had previously been perceived as a ‘post-Soviet’ country, the status of being a European neighbour.

In 2008, during Russia’s military attack on Georgia, Europe’s role in the negotiations became distinct. The then French President Nicolas Sarkozy brokered a ceasefire between the two countries. The August War caused a major stir in the European Union over security and Russia’s enhanced role. It was after the war, in 2009, that the foundation was laid for the creation of the Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative, aimed at deepening co-operation in various fields between the European Union and six countries – Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

The following years proved to be even more important for the development of Georgia-EU relations. In 2014, Georgia signed the Association Agreement (AA), which included a component of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) bringing the co-operation between the parties to a completely new level. This had both symbolic, political, and economic significance. The agreement is a roadmap for the modernization of the economy, with extensive commitments to EU regulatory norms and standards, while creating broad institutional links in the economic, intergovernmental, social, information, and civil society sectors. The year 2017 was particularly significant in terms of co-operation between the European Union and Georgia, as Georgian citizens were granted the opportunity to visit the EU Member States visa-free.

Despite considerable progress in relations between Georgia and the European Union, democratic backsliding in the country and a delay in the process of integration into Euro-Atlantic structures have become clearly visible in recent years. Western partners have recently pointed to the actions of the ruling party and the decline of democracy in the country. One of the main subjects of criticism directed at the Georgian government is the independence of the judiciary. In addition to this problem, the disruption by the ruling party of the 19 April Agreement by European Council President Charles Michel aimed at overcoming the country’s political crisis and implementing reforms was alarming. These challenges include pressure on the media and restrictions on freedom, attempts to discredit civil society, deterioration of the human rights situation, and other critical issues directly affecting the country’s democracy index. These factors led to the fact that the country was given a “perspective” rather than the status of a Candidate.

It should be noted that despite the deteriorating democracy, in the long history of integration with Europe, Georgia has never been as close to the goal as it is now. However, on the part of the country’s government, instead of actively working on the 12 priorities, we see actions that deliberately hinder the democratic development of the country. A vivid example of such actions is the “Law on Agents of Foreign Influence” initiated by the members of the parliamentary majority. The attempt to pass the draft as a law has once again clearly demonstrated that the Georgian Dream government is deliberately taking such destructive steps to suppress critical voices, discredit the civil and media sectors, and prevent their activities. The country’s democratic backsliding, delayed integration with Europe, and the activation of anti-Western narratives will lead the country to dangerous consequences, because if Georgia misses the chance to be part of this wave of the EU enlargement, Russian influence will increase, the transition to autocratic rails will become inevitable, and the country will find itself in isolation.

In addition, the unity of Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova in the process of integration with the European Union has been fundamentally important for each country for many years. The three countries are regarded as the “Associated Trio”, which have progressed more or less equally in terms of rapprochement with European structures. Taking this into account, if the Georgian government fails to fulfil the 12 criteria properly and misses the opportunity to become a candidate state to the European Union, we will see the collapse of the trio format. This will force Georgia to distance itself from Ukraine and Moldova, and most importantly, it will indefinitely postpone the consideration of the country’s membership in the EU.

History and the staunch support of the Georgian people made it clear that for Georgia, integration with Europe was never just a question of security and economic prosperity, but most importantly a question of cultural norms and values that aligned the country with the European states. This common identity was the foundation that kept the country on the European path despite multicultural influences. Georgia now has a historic and unique opportunity to realise its European identity, to bring to a logical conclusion the centuries-long efforts and path, and to become part of the European Union.