Author : Dodona Kiziria

A couple of years ago, while in Tbilisi, I had a conversation with a young man that made me very sad. Not because we were talking about some unpleasant topic, or, as Georgians are used to, because we harshly clashed with each other over opposing viewpoints on some political issue. But because I found myself in the same situation that I was in more than half a century ago when I was talking to my American students.

My debut lecture and, to put it mildly, inadequate English are described in my memoirs. But now I want to talk about something else. Every day when I entered the auditorium and began to speak, I felt like Martians were sitting in front of me. I knew absolutely nothing about them; I didn’t know who they were, what they were, what they knew, what they loved, what might make them happy or, on the contrary, which topic they might be uncomfortable discussing. I didn’t even know what examples I could give to illustrate what I was talking about. I didn’t know what books they had read, what films they had seen, what social or political events had made an impression on them. In short, each of them was for me a kind of tabula rasa, a blank board on which nothing was written, and therefore the possibility of reading anything was nil.

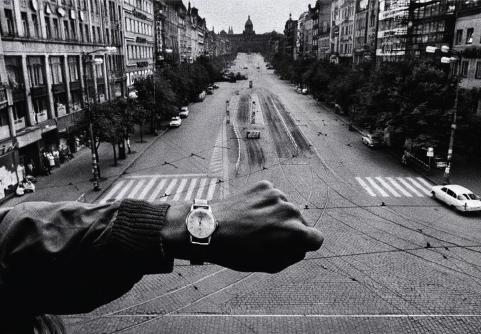

Today, a person travelling abroad for the first time would probably not have such a feeling of alienation. Television, the Internet, mobile phones, and many other sources of information have made it much easier to orientate oneself in a foreign environment. But for a person who lived in the Soviet Union at my time, abroad was an impossibly distant, galactic reality. Therefore, when arriving there, the most difficult problem was not only not knowing the language of the locals, but also the perception of human and material connections in everyday life.

My English improved day by day, albeit frustratingly slowly, but still. But for a long time, I felt how flat, empty, completely devoid of connotative layers of meaning my every word was. When you speak a language that both you and your interlocuter have known since childhood, when you speak in the country where you were born and raised, every word you utter, whether we realise it or not, is loaded with a multitude of meanings that do not require explanation. The simplest, most elementary words, such as the name of a street, the title of a book, a reference to a famous person or even a joke, contain much more information than their purely lexical expression. Each of them is accompanied by a number of meanings that the speakers know, memories associated with them, and their connotations easily taken for granted. Moreover, when you first communicate with one of your compatriots, you get an idea of this person in five minutes. What words he uses, what facts he mentions, even his manner of speaking – all this is a source of information that you perceive quite unconsciously, you receive certain information and draw a corresponding conclusion.

I certainly had no such experience of receiving or transmitting information during my first days in the United States. My students’ words, like my own, were as one-dimensional and lacking in depth as sentences illustrating some grammatical rule in a foreign language textbook. Here, for example: “Libreville is the capital of Gabon”, “The children are playing in the yard”, “Robert has two brothers and a sister”. Here, each word, devoid of any connotation, is the bare denotation. I’m sure that a significant part of my readers have no idea and don’t really care where the city of Libreville is and what it looks like, what kind of children’s game we’re talking about (football, basketball, ball, dodge ball, whatever) and, of course, it doesn’t matter who Robert is and what the names of his brothers and sisters are. The key is to learn how to put words together, use the verb in the right person, and so on. That was my main task – to make a grammatically correct sentence. How precisely the words were chosen, how well their connotations matched what I was trying to convey – it was hard for me to even think about it.

Half a century has passed since then. During those years, my “Martian” students have turned into quite ordinary, normal people. I have long since retired, but many of them still remember me and write to me their stories, recall my lectures, tell me about their activities. When I send them a reply, I am no longer flipping through a dictionary with trembling fingers, no longer looking for the right words to express this or that thought. We understand each other perfectly, regardless of whether we agree with each other on this or that issue.

The problem is that, for me, part of the Georgian youth today is like a tribe of Martians. We speak the same language, more so in the country where we were born and raised, though of course several decades apart. We have a lot in common. But I listen to them, or look at them, and feel that my words to them are as empty and meaningless as “Libreville is the capital of Gabon”. I do not know who they are, what they care about, what they worry about, what they dream about. How do they perceive the Georgian language – as a mother tongue or simply as a means of communication? In general, is this word, “native”, acceptable to them, or is it a sentimental, time-consuming, and lexical unit devoid of inner meaning?

Obviously, a certain alienation between generations is a common thing, old people don’t always find a common language with the young. But for me this alienation is deeper, more insurmountable, and more painful. I wish I knew who they are, what they are, what they want, what they care about, and what they lack. Is Georgia a homeland for them or just a place to live that is different from other countries only in that life is less comfortable here?

How I wish I knew...

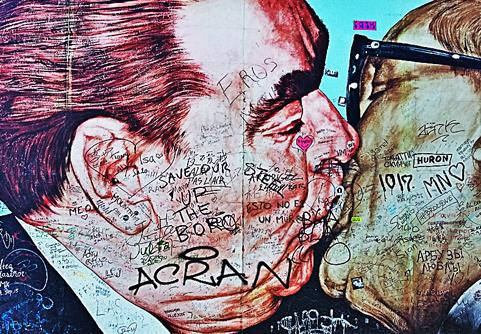

P.S. This article was written in the last days of February. Looking at the events of 7-9 March, the author wrote these words in a social network: “These last days have responded to my thoughts. I was dead and came back to life! Thank you, my good, my favourite, beautiful, intelligent boys and girls, my friends, acquaintances, and strangers. Georgia belongs to you; you must defend it from barbarians and the Kremlin’s henchmen. You must win!