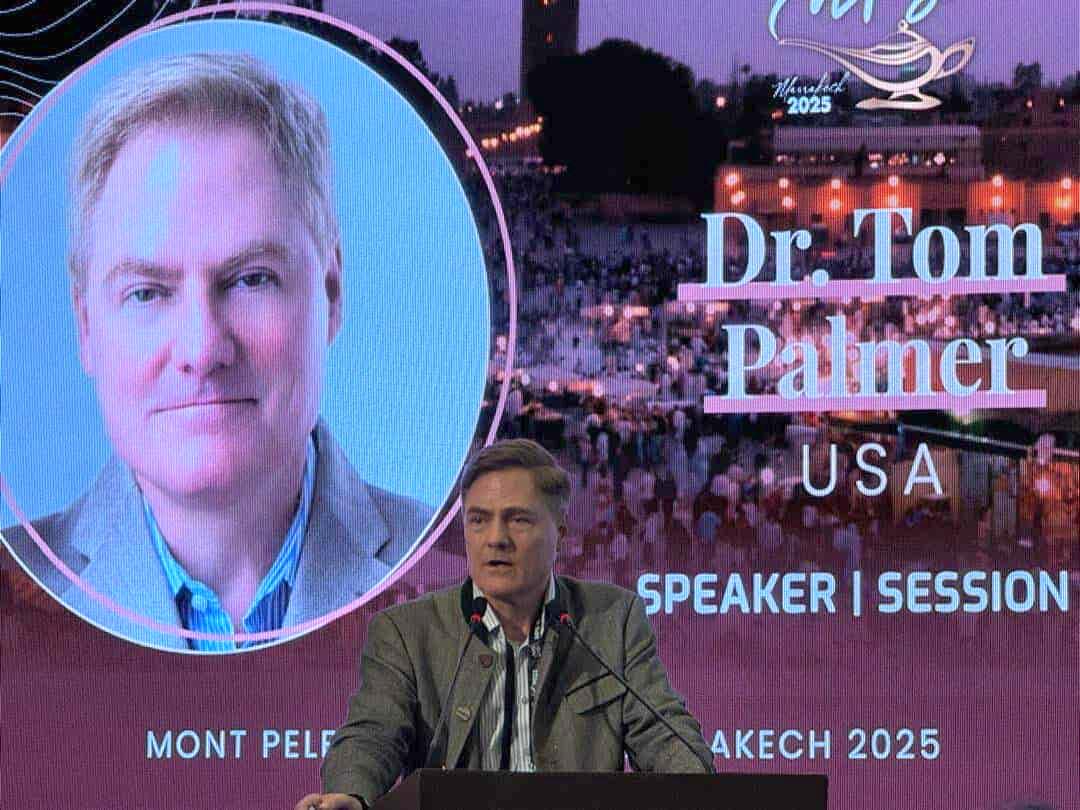

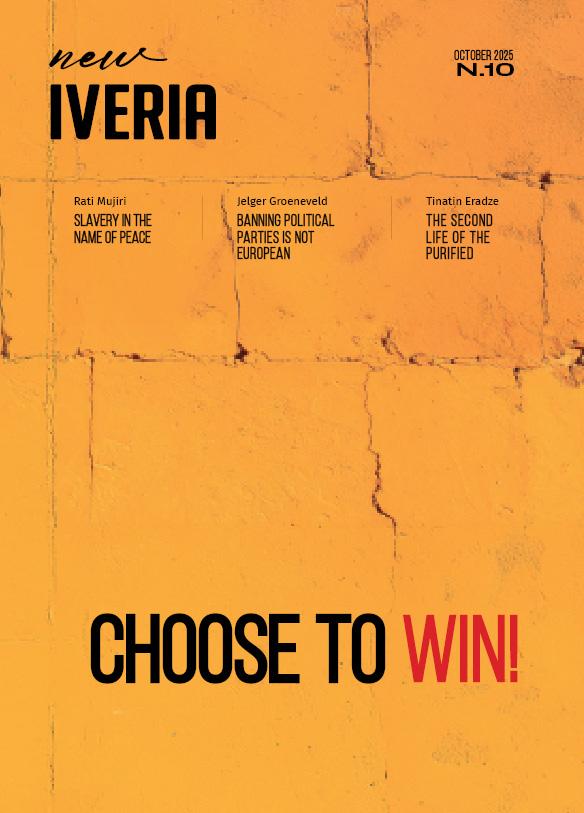

Interview with Tom Palmer

Author : Tom G. Palmer

The New Iveria spoke with Tom G. Palmer, a social theorist, political scientist (Oxford D.Phil.), and long-time activist for liberal principles. Tom smuggled forbidden literature, photocopiers, and other tools into Communist countries in the 1980s and has worked globally with classical liberal think tanks. He is affiliated with many organizations, including the Fundación para el Avance de la Libertad in Madrid, the Cato Institute, Atlas Network, and IES-Europe. The views expressed are his own.

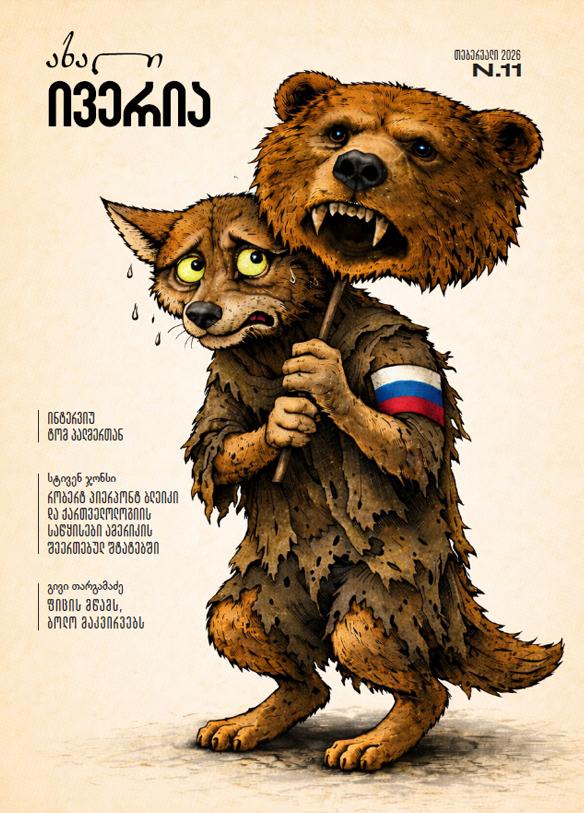

2022 წლის 24 თებერვალს რუსეთის მიერ უკრაინაზე განხორციელებული სრულმასშტაბიანი აგრესია შეუქცევადი გეოპოლიტიკური ძვრების დასაწყისი გახდა. თებერვლის იმ მძიმე დღეებში ალბათ ვერავინ წარმოიდგენდა, რომ ომი 1400 დღეზე მეტხანს გაგრძელდებოდა და ხანგრძლივობით „დიდ სამამულო ომსაც“ გადაუსწრებდა, თან ისე, რომ ომის მეოთხე წელს რუსეთის გლობალური გავლენები შესამჩნევად შესუსტებული იქნებოდა.

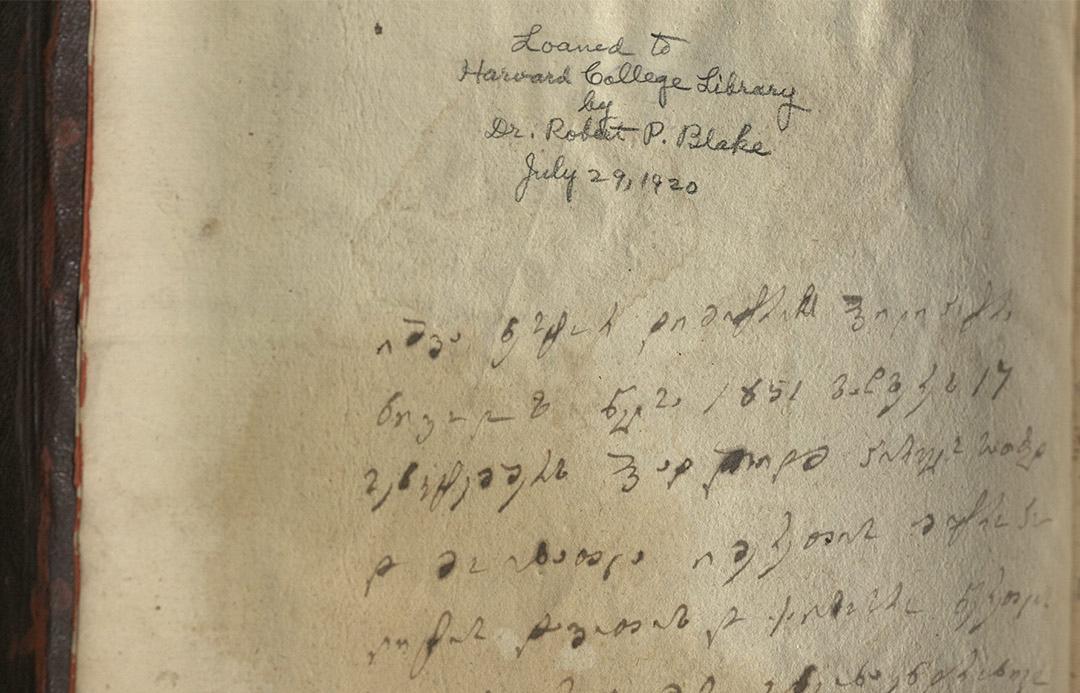

საქართველოს შესახებ ცოდნამ ამერიკის შეერთებულ შტატებამდე გვიან მიაღწია. ევროპელ მოგზაურებს, ვაჭრებსა და მისიონერებს საქართველოსა და კავკასიასთან გაცილებით ადრე ჰქონდათ შეხება. შავი ზღვა და აბრეშუმის გზა უხსოვარი დროიდან იზიდავდა როგორც ევროპის სავაჭრო იმპერიებს, ისე სახარების მქადაგებელ მისიონერებს, განსაკუთრებით ვატიკანიდან. ამის ნათელი მაგალითებია კათოლიკე მისიონერები - არქანჯელო ლამბერტი და დონ კრისტოფორო დე კასტელი, რომლებიც XVII საუკუნეში ქართული კულტურისა და ადათ-წესების გულმოდგინე მკვლევრებად ჩამოყალიბდნენ.

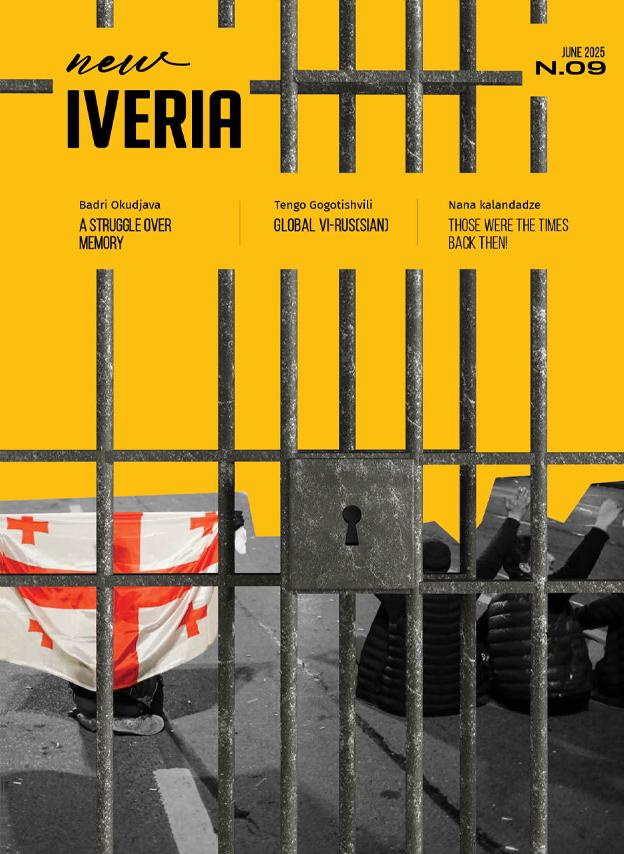

სიმართლე თავის გზას ყოველთვის გაიკვლევს და სიმართლე უზრუნველყოფს რეჟიმის გასამართლებას. გასამართლებას არა მხოლოდ აქ, დანაშაულის ჩადენის ადგილზე, არამედ საერთაშორისო თანამეგობრობის წინაშეც. შესაბამისად, პასუხისმგებლობაც მრავალგვარი იქნება - როგორც სისხლის სამართლებლივი, საპატიმრო, ისე ფინანსური, მათთვის ყველაზე მტკივნეული და მორალურიც, რაც ალბათ, ყველაზე ნაკლებად ადარდებთ, მაგრამ მაინც.

იმ დღეს ჩემს თავზე რაღაც გასკდა. ზუსტად თავს ზემოთ. ნაცნობი ხმებიდან ეს ხმა ყველაზე მეტად აფეთქებისას ჰგავდა. ჭურვის აფეთქებისას. მაგრამ არ მოჰყოლია დარტყმის ტალღა. არავინ მომკვდარა, ცეცხლი და ბუღი არსად ავარდნილა.

პეტრეს დილემა

Author : Keti Kurdovanidze

„გულში დიდი ეჭვი ჩაუვარდა. ეხლა მარტო იმის დარდი ჰქონდა, შეეტყო — რაში ტყუვდება: იმაში, რომ ეს მართალი თვალთმაქცობაა და ტყუილი ჩამორჩობა, თუ მართალი ჩამორჩობაა. სწორედ გითხრათ, პირველში მოტყუებას, უფრო ჰთაკილობდა მისი გული: აბა თვალთმაქცობამ ტყუილი მართლად როგორ უნდა მაჩვენოს ამ დროულ კაცსაო. და მართალი-კი რომ ტყუილი გამომდგარიყო, ეგ არაფერი; მაგას როგორღაც უფრო ადვილად ჰყაბულდებოდა ჩვენი პეტრე.“

2007 წელს მშვიდობის, დემოკრატიისა და განვითარების კავკასიურმა ინსტიტუტმა, ფონდ კორდეიდის (ჰოლანდია) და საზოგადოების ინსტიტუტის კვლევითი ცენტრების ფონდის (უნგრეთი) მხარდაჭერით, გამოსცა სერია „საზოგადოება და პოლიტიკის“ მეექვსე წიგნი, რომელშიც სხვა სტატიებთან ერთად დაიბეჭდა ქართველი მეცნიერებისა და მკვლევრების წერილები „10 შეკითხვა საქართველოს დამოუკიდებლობის 15 წლისთავზე“. ათვლის წერტილად აღებული იყო დამოუკიდებლობის საერთაშორისოდ აღიარება, ანუ 1992 წელი.

ბოლო წლებში კვლავ აქტუალური გახდა ქართული კულტურულ-პოლიტიკური იდენტობის საკითხი. ლიბერალურ ვექტორს კონსერვატიული ცვლის. იმისთვის, რომ ცვლილება ქმედითი იყოს, იგი სიმბოლურ დონეზე უნდა მანიფესტირდეს. ამიტომ ეროვნული ჰაბიტუსის სიმბოლური მანიფესტაცია პოლიტიკური საკითხი გახდა.

მორჩილების ფსიქოლოგია

Author : Ioane Tetiashvili

- ლევ ტროცკი ხომ თქვენი ფანი იყო. თქვენც თანაუგრძნობდით.

- სანახევროდ. ეგ ამბობდა, რომ რევოლუციას თავიდან სისხლი და გვემა მოჰყვება, ცოტა ხნის მერე კი ხალხი მიიღებს საყოველთაო ბედნიერებასო. ამაში სანახევროდ ვიყავი და ვარ დარწმუნებული, იმიტომ რომ ამ აზრის მხოლოდ პირველი ნაწილის მჯეროდა. - ირონიული ღიმილით უპასუხა ინტელიგენტური გარეგნობის ხმელმა მოხუცმა.

თბილისი ჩემებურად...

Author : Nana Kalandadze

თბილისზე მინდა დავწერო, მე რომ გავიზარდე, იმ დროის თბილისზე! უამრავი ფაქტი, სურათი, მოგონება მეხვევა თავს, მაგრამ არ ვიცი, საიდან დავიწყო... ახლა ისეთი რამ დამემართა სკოლაში ქართულის საკონტროლო წერის დროს, „თემის“ დაწყება რომ გიჭირდა და შეიძლება რვეულის ფურცელიც ამოგეხია საკუთარი პრიმიტიულობით შეწუხებულს.

აფხაზეთში საომარი მოქმედებების დაწყებიდან ორ დღეში, 1992 წლის 16 აგვისტოს, ქართულმა საჯარისო ნაწილებმა განახორციელეს საზღვაო დესანტირება გაგრის ზონაში. იმ პერიოდში საქართველოს სამხედრო დანიშნულების მცურავი საშუალებები არ გააჩნდა, ამიტომ შევარდნაძის ხელისუფლებას „მეგობრული დახმარება“ რუსულმა არმიამ გაუწია. სეპარატისტული პროპაგანდა რუსეთის ამ ნაბიჯს დღემდე ისე ფუთავს, თითქოს აფხაზთა რიგებში დაბნეულობის შესატანად, დესანტირებისას ქართულმა სამხედრო კატარღებმა რუსული დროშები აღმართეს გემებზე.

დისტოპიური რეალობა

Author : Irakli Laitadze

ერთმა ძალიან ჭკვიანმა კაცმა თქვა - რაც არ გვკლავს, გვაძლიერებს. მე ასე არ ვფიქრობ. თუ უნივერსალურ გამოთქმას (ან ფორმულას ან მოვლენას) აქვს გამონაკლის(ებ)ი, მაშინ ის ვერ იქნება უნივერსალური. სიტუაციამ, მდგომარეობამ შეიძლება არ მოკლას ადამიანი, მაგრამ, ამავე დროს, შეუძლია დიდი ხნით დაუზიანოს ფსიქიკა. ჩემი აზრით, თუ ადამიანი განსაცდელის მერე ისევ ძლიერია - ასე ხდება არა გადატანილი გასაჭირის გამო, არამედ ამ გასაჭირის მიუხედავად. განსაცდელი მხოლოდ აშიშვლებს იმას, რაც უკვე ჩვენშია.