Author : Keti Kurdovanidze

Exactly a century separates us from the time when Mikheil Javakhishvili published his landmark novel “Jaqo’s Khiznebi”, which, like Ilya’s Is This a Man?, has come to symbolize its era. What happened to us, how we got sick, and how we were to recover – this is what both writers pointed out to us. One was killed by Georgian Bolsheviks in the service of the Soviet Empire, the other was tortured and shot by them. Such a cruel verdict was passed precisely because of the epochal significance of these texts. Both writers attributed the cause of our ills to cultural and anthropological degradation. Indeed, the social marginalisation of personalities, the loss of traditional, practical, and cultural ways of life led to a crisis of social cohesion and ultimately to its disintegration, as an individual’s culture is closely linked to their sense of identity and belonging to society. This is why Ilya said: “I write about the social plague.”

In the novel, neither Luarsab Tatkaridze nor Teimuraz Khevistavi are able to adapt to the times, they are disconnected from the socio-cultural system of the past and have difficulty understanding the present. Despite this, the cultural anthropology of these two characters is quite different: Luarsab lacks self-reflection, which is due to his illiteracy, mythological thinking, and social irresponsibility. That is why only anthropological rubbish remains of him. With great suffering Teimuraz still manages to self-identify, understand the past, and return to faith. A new man is born in him, for his problem is not his upbringing or social irresponsibility, it is simply that Teimuraz must learn to revive and use this knowledge.

It is the reflection of the combination of these two characters that is the public capital of post-Soviet Georgia, the 90s, when the new political and cultural reality became a similar challenge for everyone. Who chose to be Luarsab and who chose to be Teimuraz became clear in just one year. Who felt social responsibility and who joined the imposed cultural genocide of the occupying country, which led to despair, nihilism, polarisation, frustration, and, finally, collapse.

The collapse and degradation of values became the basis for the new challenges of the new century. And while the whole of the civilised world was taking important steps towards technological progress, the people of Georgia, like the Neanderthals of the Palaeolithic era, were warming themselves around a fire lit in the street.

Who is to be blamed for this – the Luarsabs or the Teimurazes? Undoubtedly, both simultaneously, given that totalitarian regimes’ allies extend beyond the Jaqos to include the Luarsabs and the Teimurazes. The Luarsabs represent cultural stagnation, while the Teimurazes symbolize cultural degradation. The Jaqos gain an arena by adapting to this scene.

This nourishes, fortifies, and reinforces the system, whose mechanism operates effectively and sustainably under such favourable circumstances. The existence of the Jaqos is determined by the living dead Luarsabs and Teimurazes. Something must be viable, and unfortunately this viability is determined by collaborationism and mediocrity, when one part of society enjoys itself and the other part declares capitulation.

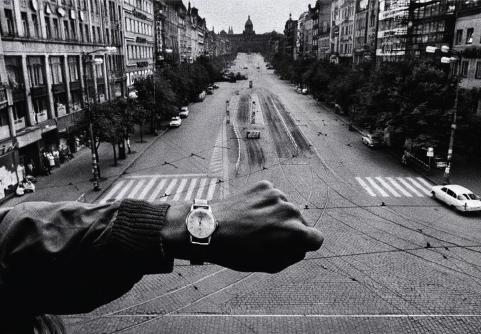

Time flies and waits for no one, which is why it is so important to understand what it requires of us. Knowing the needs of time was considered by Ilya to be the secret for the survival of this small nation with a difficult history, because the failure to understand these needs is what gives rise to the problems of the Luarsabs and the Teimurazes.

When does the crisis of Luarsab begin? Just when his diminished skills, limited mind and infantilism cannot cope with reality – the big lies and betrayal when an ugly wife is slipped to him instead of a beauty. After this social failure, he, like the Georgian voter, tries to find a friend and admirer in the very person who first disappointed his adolescent hopes. Hence begins conformism and accommodation, moreover, the accommodation of one’s own dreams to a forcibly imposed situation. And then he gets so accustomed to it that he becomes contented and even happy. And although this fact still imposes a fatal imprint on his life, he refuses to fulfil his social functions in the interests of the society that cheated him. He chooses a different path – to consume his possessions in his own pleasure, in the way he understands this pleasure, to define the existential dangers that now threat the idyll created with his own efforts. These are: education, books, schools, the advent of the new age, the wrath of God, a brother having his eye on the property of the heirless Luarsab, who becomes the image of an enemy.

How does Luarsab cope with the pain and fear, how does he try to get out of this crisis? He talks to Darejan about these fears and threats, has a discussion with her, shares with her like his equal, shares the actual cause of his misfortune. And each time he hears from her comforting words and a cherished promise that they will soon have a child to spite David, the same David who has become the dilemma of their lives. It is these promises and consolations, the blunt self-deception and illusions that legitimise the nothingness created by Luarsab, and Darejan is the narrator and inspirer of all this bestial existence. Darejan dies, and Luarsab dies too, because the purpose of his existence has disappeared. With Darejan’s death, being “Luarsab” loses its basis.

The adventure of Teimuraz develops in an altogether different way. His identity crisis emerges in the process of adapting to the times. Having once been a prince, a lawyer, a man, a married man, destitute, and sheltered in Nashindari, Teimuraz is cut off from the context of a past, cultural memory. He has no basis for the starting point of his identification, and the environment he lives in is unstable and prone to decay and deconstruction, with the disappearance of ideas, meanings, morals, and values. The depersonalization of Teimuraz begins when he can no longer perceive the objectivity of the real world and his own status in this reality. He no longer has a clear self-awareness or a clear ability for self-analysis; in some ways he resembles a fictitious subject of the postmodernist narrative – a moth whose vital integrity, organisation, and consistency are broken, and whose context of personal, everyday life is dysfunctional.

In his everyday life, he is in a state of fundamental, absolute alienation, because he meets the new times unprepared. He lacks neither knowledge, education, nor social activism, but he lacks the skills to cope with the challenges of the time, he is unable to create a new narrative, and his lack of eloquence testifies to this. Besides, there are objective circumstances – his historical estate is occupied, and his personal space is getting more and more narrow, so that he finds himself in the same room with his only friend – his wife – and his honour, which, together with his knowledge, has long since ceased to function. All this makes impossible the personalisation of Khevistavi in the environment that Jaqo offers. Not only is the material culture occupied, but also Teimuraz’s personal space – cultural affiliation, consciousness, self-awareness, and even values. And Teimuraz, with his blind eyes, cannot see the threat to his honour, estate and inheritance posed by the preferences granted to Jaqo.

The contradictory nature of the new reality, the fracture of cultural constructs and, moreover, the anthropological crisis determine Teimuraz’s disappearance as a human image. Why does he give up his abilities, why does he succumb to apathy, why does he lose faith, why does he try to commit suicide – because it is this sense of particularity that prevents him from integrating into reality. He refuses to work at school, but he does not shy away from working in Jaqo’s canteen, because he believes that he cannot teach a child what he does not believe in himself, and he is right. This is why Teimuraz’s Odyssey is so chaotic and fragmented.

Amidst profound despair, anguish, and extreme decline, the “dispossessed of Jaqo” gradually comes to the understanding that he is guilty before Margo for the creation of this feral being endowed with his property, conscience, past, and future. He is held accountable for handing Margo over to Jaqo, and Margo attempts to elevate Jaqo by instructing him in literacy, writing, sewing, as well as personal hygiene and grooming, in order to imbue this creature with a cultural framework and thereby rationalize her cohabitation with her.

Teimuraz’s self-reflection and self-immersion begins with the realisation that he as a person and Margo as his cultural belonging are in danger, a danger brought about by revolution, a revolution that opposes the dialectical laws of development and is a consequence of inevitable necessity. That is why, where revolution occurs, culture has no place, it goes into decline or passes into passive memory, because, according to cultural relativism, cultures develop according to historical circumstances and not in a linear progression from the “primitive”.

Teimuraz realises that to facilitate communication, he must activate the passive memory. By focusing on Margo’s return, engaging in social activities, refining knowledge and memory, the “destitute” experiences that he has got rid of the smell of the dog’s corpse forever. Now he is alive and waiting for the return of what he has voluntarily given to his wild offspring, whose viability is determined only by circumstances, because Jaqo does not exist on his own, and therefore cannot create anything and become a culture. This is why Jivashvili is so keen to give his son the surname Khevistavi. Jaqo is a dormant essence that is immediately awakened when the personal culture begins to fade away. Therefore, his existence depends on our vitality, and it can only be achieved through action, struggle, and endurance.

So, it is today, in the most challenging time for our country, with the only difference being that our wait time is over.