Author : Teo Khatiashvili

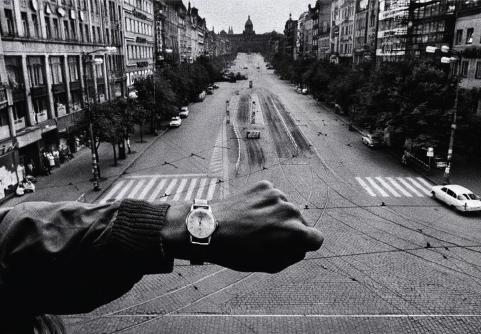

sind das für Zeiten, wo Ein Gespräch

über Bäume fast ein Verbrechen ist

Weil es ein Schweigen über so viele

Untaten einschließt!

What times are these, when

A conversation about trees is almost a crime

Because it entails a silence about so many misdeeds!

Bertol Brecht

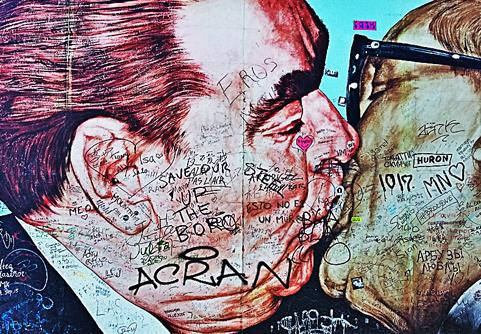

As early as the 1930s, Walter Benjamin, arguing about the essential transformation of art in an entirely new technological era, believing that the final departure from the sacred would radically alter its social function and establish it in place of ritual and religion in another practice, politics.

A little later, one of the main slogans of second-wave feminists – the personal is political – would transcend the texts and rhetoric of feminist theorists and authors alike.

“Ultimately, all films are political,” the most overtly personal filmmaker in the history of cinema, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, whose personal experience becomes a poignant tool for exposing the hidden traumas of post-Nazi Germany and the Nazi legacy of his own era, said in an interview.

How is it possible for a person – I would add, even more so for an artist – to be apolitical in an era so radically different from the previous, pre-modern era? This question is the subject of judgement for many philosophers. For Hannah Arendt totalitarianism is formed and revived not only and not so much by one tyrant (leader/führer) and the political elite close to him, but his existence requires an apolitical crowd characterised by indifference to political processes. Both the National Socialists and the Communists would address this faceless mass of the population, standing apart from politics, and would feed them with appeals and populist slogans.

I believe that an apolitical artist and the art is a kind of oxymoron, if only because the artist’s freedom is a political issue.

This is my editorial column from the last (fifth) issue of Kin-O magazine, which is no longer in print, and so I offer it in its entirety. I think it will give you an idea of the content and main theme of the issue, as well as shed some light on why the film centre that funded the magazine had refused to print it.

To be precise, they didn’t refuse me – it was just that according to the standards established in the cultural sphere during the tenure of Tea Tsulukiani, there was a completely non-transparent and closed system. I hadn’t received an answer for months: First, in December, the tender prepared to determine the contractor printing house was cancelled and postponed until the new year. Then they were waiting for the approval of a new budget, and without the approval of the budget the fate of the magazine couldn’t be decided, so I offered to find the money for the printing myself, which was rejected. In the end, they didn’t agree to the simplest solution – to upload the electronic version on the website of the Film Centre. Or rather, the answer (I’d rather call it mumbling) was still unclear, “We don’t know, we’ll see, we’ll ask the director”.

The new director of the Film Centre, aka Deputy of Minister of Culture Tea Tsulukiani, is almost a Godot character (in general, Beckett is very appropriate for describing this institution), whom the staff do not even know, and with whom it is almost impossible to communicate even virtually, for all apart from 1-2 confidants.

This unhealthy atmosphere is also mentioned in a harsh letter of the magazine, in which the author (Basti Mgaloblishvili) analyses cinema from a historical point of view as a means of propaganda and, on the contrary, as a means of provoking resistance and protest movement.

Overall, the theme of the last issue, the relationship between art and politics, is an issue that Georgian Dream propaganda has been trying to fight against since its first days in power. The war between Ukraine and Russia has highlighted the hypocrisy of attempts to separate art (sports, business, etc. or any citizen) from politics. The cultivation of apolitical artists (successfully used in election campaigns) in the context of the war that is vital for us has finally led to the idea of an apolitical or neutral state, while the entire world is involved in the anticipation and establishment of a new order.

Therefore, despite – or perhaps because of – the confused, unclear answers and the time delay, I can already say with certainty that the magazine was banned and, according to the old and, as it turns out, unforgotten practice, “put on the shelf”. As Mako Chilashvili, Deputy Director of the Film Centre, said in a television commentary, this issue “expired, fell out, it happens”. Incidentally, the amount spent on the preparation of this expired magazine (editorial staff and authors’ fees) is almost four times more than the amount allocated for its publication. It seems that it is more reasonable for the Ministry of Culture to waste the state budget than to reproduce unwanted thoughts.

“There is no such thing as uncommitted criticism, any more than there is such a thing as insignificant art. It is merely a question of the openness with which our commitments are stated. I do not believe that we should keep quiet about them.” —This quote from Lindsay Anderson’s polemical article, “Stand up! Stand up!” (1956), which became a manifesto of the “angry generation” of English cinema, turned out to be symbolic. Indeed, “these are the times when talking about trees is a crime because it involves a silence about so many misdeeds!”

.