Author : David Zedelashvili

In the indefinite future, a masterpiece of fiction in the Georgian language may be created that critically describes Georgian society in 2012 and the subsequent period of the democratic transfer of power to the Georgian Dream, strengthening of its political regime, and consolidation of social order. However, even if such a text is never written, its place will be boldly taken by the novel Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming by the famous contemporary Hungarian author László Krasznahorkai published just a few years ago (translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet, 2019).

“Baron”, as the author refers to the book, is the third part of a trilogy; the previous two books, Satantango (translated from the Hungarian by George Szirtes) and The Melancholy of Resistance (translated from the Hungarian by George Szirtes) had already received international acclaim by the end of the 20th century. According to the author himself, he wanted to write only one book, which eventually became a trilogy, in the final part of which he fully conveyed what he had to say.

We cannot and will not engage in an in-depth analysis of Krasznahorkai’s still-in-progress literary legacy, but the trilogy culminating in Baron includes, along with many literary virtues (the analysis of which literary scholars will be engaged in for a long time to come), outstanding examples of political and social commentary.

Krasznahorkai’s trilogy takes place in fictional towns of Hungary, places forgotten by both God and man, where more than just material destruction, but also the destruction and collapse of society, is noticeable. Whereas in the first two novels of the trilogy, Satantango and The Melancholy of Resistance, the almost surreal characters of a crumbling social fabric diluted by the acidic shroud of Krasznahorkai’s black irony miraculously find themselves in a new order, the finale changes form in The Return of the Baron where a catastrophe occurs and a morally degraded society is physically destroyed.

The first two novels of the trilogy, especially The Melancholy of Resistance, feature an apocalyptic aura of the end times. The reader gradually realizes the complete absurdity and comicality of this feeling. The announced end times will never materialize. Even the characters, who entertain the reader with their chaotic fuss and are sometimes deserving of empathy, unwittingly find themselves in a new social order, a new “normality” into which they suddenly fit organically.

The Melancholy of Resistance can be read as a radical critique of recent religious, secular, and, in particular, political uses of different versions of the philosophy of history. The end of times is endlessly postponed, and the closer it seems, the faster it slips away. Krasznahorkai’s characters, who perceive the chaos of a collapsed social fabric as the last times, struggle with history and time. In this struggle they do not take history into their own hands, but neither do they become puppets in the hands of it.

Accordingly, in The Melancholy of Resistance, Krasznahorkai shows the possibility of human freedom. Despite the fragility of the social order, which has to be created and maintained over and over again, an individual can create and maintain this order without becoming a puppet of history and can transform himself into the subject by his own action.

The Melancholy of Resistance shows the possibility of freedom for “little men” in a society constantly under the threat of collapse. This is an important development since Satantango, where the people trapped on the collective farms of communist Hungary are tempted to choose a messiah from their ranks and attach to him the hope of establishing a new society. This hope turns out to be false, the Messiah turns out to be a fraud, although the revelation of this still does not cause a collapse.

Accordingly, The Melancholy of Resistance brings a kind of spark of hope to the “little men” disillusioned with the Messiah, showing that even the “little men” can become subjects, fight against history, and find freedom in the social order that is inevitably created, if they decide to take responsibility for their subjectivity and actions and to show initiative.

Baron’s Homecoming returns the motif of the Messiah to the disintegrating society of a provincial Hungarian border town. As in the previous two novels of the trilogy, the disintegration of society is shown here by strange events: a famous professor goes insane, sells everything, and builds a hut not far from the town, in an area overrun by thorn bushes. His unacknowledged son visits the professor in the hut, accompanied by journalists, and asks his father to acknowledge him as his son. To get rid of the uninvited guests, the professor fires a shotgun into the air.

After the incident with the gun, the story of the professor’s disorder spreads through the town. The professor’s former housekeeper, Aunt Ibolika, becomes upset and comes to the old master’s hut, serving her famous pie. Aunt Ibolika tells the professor that she will never leave him, because in her family it has always been the rule: if you serve someone, you serve him for all your life.

However, Aunt Ibolika has an important story to tell the professor. She informs the former landlord that things will soon be different, that Baron Wenkheim, from an aristocratic family that once ruled the town, is returning home from Argentina. Aunt Ibolika remembers the Baron and his family, she and her family served them long ago, during “the old good times”.

But now that the Baron is on his way, Aunt Ibolika also believes what the whole town is already saying: that things will be different with the Baron’s return. The fever of the Baron’s return, the new lord of old, is gripping the whole town.

Residents of this small town are not the only one feeling nostalgic for their old overlords. On the train to Budapest, Baron Béla Wenckheim, the novel’s protagonist, must listen to the conductor expressing his longing for the Hungarian communist dictator János Kádár:

“Things were different in Kádár’s time. Kádár provided everyone with work, bread, and housing.”

No, the conductor doesn’t want to go back to Kádár’s time, he just wants to continue the life he had. A life where everything was always in short supply and somehow everyone got by.

In anticipation of the Baron, his little town is gripped by a general fever. Everyone is waiting for the appearance of the Baron’s unheard-of wealth in this forgotten town whose only function is to receive tourists and those tourists have long abandoned it. The employees of the travel agency, who are out of work, are the clearest example of the disintegration of the town’s society.

However, only one of these employees, young Dora, who is caring for her ailing father, has retained any sanity. The flabbergasted Dora tells her father that the townspeople are so confident in the Baron’s abilities that they are already spending the Baron’s money – the large pile of money they think the Baron will bring. At the dinner table, Dora breaks into bitter laughter, “Do you believe that, Father?” They have already spent the Baron’s money before he has even arrived.”

No one in the town even questions what the Baron will do with his countless wealth – of course, he will give it away! Why else would he come back? Believing that the Baron is about to distribute his wealth, everyone prepares to become the chief vizier at the Baron’s court, so that the Baron will spend his vast fortune according to their plan. The Mayor and the Chief of Police, the nominal and real rulers of the city, are all waiting for this.

The Mayor is preparing the entire town to welcome the Baron. The Baron’s arrival will put an end to both the failed experiment with democracy and the chaos it has created, at least that’s what the town head, himself a democratically elected official, thinks. The Mayor develops a programme to welcome the Baron – he evicts the orphans from the Wenkheim family château, now an orphanage, in order to beautify it for the Baron’s arrival. Moreover, in agreement with the chief of police, the only business operating in the town – a chain of slot machines run by the town management – is temporarily shut down.

The reason for this is that the Baron’s penchant for gambling is known even in his hometown. However, they do not know the true reasons for the Baron’s return. The town does not know that the Baron sacrificed his entire family fortune for his love of casinos and almost lost his freedom. Béla Wenckheim’s wealthy Austrian relatives bail him out of his debts in Argentina and set strict conditions that he should live in such a way that his Argentine adventures would never tarnish the Wenkheim name.

The Baron agreed to his relatives’ terms and travelled to his hometown in Hungary with a train ticket bought by them. Baron Wenckheim, whose bags of money the whole town is waiting for, has nothing but a few hundred euros given by his relatives for the trip and a wardrobe made by them distributed throughout several suitcases.

Bela Wenckheim’s only reason for returning to his hometown is to see his childhood love Marika and renew his relationship with her. He even sends her a touching letter from the road, turning Marika’s dreary old age upside down. The Baron doesn’t understand what the owner of a temporarily closed slot business, who has imposed himself on him as his train companion and offers himself as his personal secretary, wants from him. Even more puzzling is the pompous ceremony at the station where the whole town gathers to welcome him.

The Baron loses his meaning of life when he meets Marika, and instead of the image of his childhood sweetheart that he imagined in his fantasies, he sees a dying old pensioner just like himself. The distraught Baron decides to commit suicide and runs to the railway tracks, but on the tracks, he changes his mind and decides to return. Due to the force of the black irony inherent to Krasznahorkai, the Baron is hit by a belated locomotive in need of repair and killed.

The shock of the Baron’s death is followed by the realisation of those waiting to spend his fortune that his wealth had never existed. Moreover, they do not even find the few hundred euros that the Baron’s relatives gave him as travelling money.

The death of the Baron brings the process of the town’s collapse into an irreversible phase. Suddenly an apocalyptic situation arises. The editor of the town’s main newspaper receives an anonymous letter that claims to be a kind of moral mirror not only for the town’s society, but also for the entire Hungarian nation. The letter, whose style is reminiscent of that of Thomas Bernhard, pours out a torrent of perpetual rebuke, showing the moral degradation of the city and Hungarian society as a whole.

The author of the letter calls the Hungarians the most hated nation in the world and asks the Hungarian gene to cease existing and reproducing. From this continuous stream of curses comes the most scandalous sentence of the novel: “Being Hungarian is not belonging to a nation, but a disease, an incurable, terrible disease, a calamity of epidemic proportions.

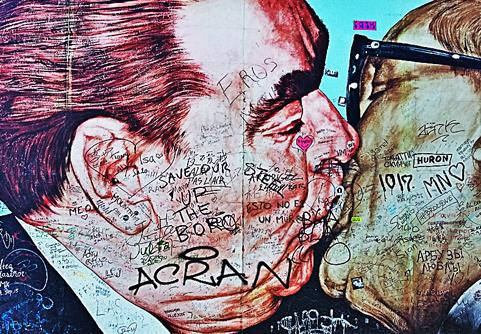

“They are all slaves to some extent, for slavish obedience is one of the deepest elements of the vile Hungarian soul,” writes the anonymous author, leaving open no question as to why the town should be destroyed, just as it is in the book finale.

The counterbalance to slavish submission is contempt for all that is genuinely great and a desire to destroy the truly great at the first opportunity. The manifestation of contempt for truth is also the pillar of the submissive spirit – the lies and deceit. The author of the letter considers these two to be the only “values” of the Hungarians: “They know how to lie in two directions at the same time, on the one hand, outwardly, to others, and on the other hand, inwardly, to themselves.”

Present-day Hungary, like Georgia, is an illiberal socio-political regime for this very reason. Their people do not adapt to systemic lying but consider it organic and natural. Everyone lies, both those in power and their servants. Everyone deceives each other and themselves – they lie and deceive themselves that they elect authorities democratically; they lie and deceive themselves that they are free and their rights are protected; they lie and deceive themselves that the authorities are bound by law and safeguard the rule of law.

Moreover, this systemic lie machine is a self-sufficient and self-reproducing regime that basks in its own bubble. The regime has this quality because self-deception works well in another respect as well – it is not entirely indifferent to the joys and sufferings of others.

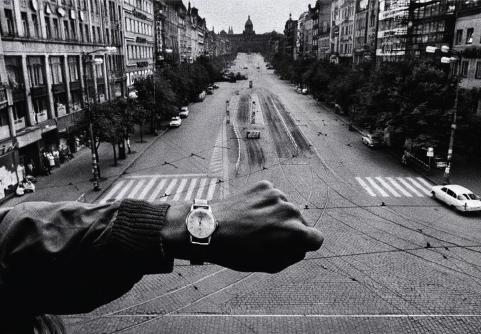

Now, against the background of the immoral policy of the illiberal regimes of Hungary and Georgia, tolerated by their own people, the words of the anonymous author of the letter sound alarming: “...it is impossible to imagine a more indifferent people than the Hungarians. It so happened that next to them, 20-30 kilometres from the border, a terrible war was going on and they continued to live happily...”

Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming shows the moral decay of society, preparing to kneel to its master. As unacceptable as it may be to the liberal mind, a slave spirit can be formed voluntarily. Illiberal regimes cannot exist without such social footing. Their fodder is the people’s choice to live in a systemic lie, and they will exist until the people topple down the tower of lies they themselves have created.