Author : Giorgi Astamadze

Russia’s imperialist expansion in Ukraine in 2022 had a significant impact on Georgia, exposing the hybrid regime which had ruled the country under the guise of pro-Westernism since 2012. Although the deeply anti-Western nature of the regime’s figurehead, oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, was apparent to keen observers from the start, it took a full decade—and the Russian invasion of Ukraine—for the façade of he and his entourage (encouraged by pro-European parties gathered around him) to crumble, and for Ivanishvili’s true stance to be revealed.

Since 2022, the Ivanishvili regime has entered into open confrontation with the civilized world, accusing the West of trying to drag Georgia into war and of using all possible means - rhetoric and action - to isolate Georgia from the West. Representatives of the regime, whose political past is so insignificant that it may often be easier to remember their serial number on the electoral list than their name, berate Western diplomatic missions in Georgia on a daily basis. In reality, the fact that Georgia is an independent country and its claims to be part of the democratic world are largely attributable to the existence of these missions and their friendly policies.

Reflecting on these developments, I asked myself if there had ever been a moment in Georgia’s recent history when the Georgian government had so blatantly offended Western missions. Even during the Cold War during the Soviet era, there wasn’t such vulgar anti-Western sentiment as we see today emanating from Putin’s Russia and its satellite regimes, including the Ivanishvili government, with its controlled TV stations and factories of trolls and bots. In terms of historic parallels, the Ivanishvili regime bears a striking resemblance to the first generation of Georgian Bolsheviks, who, in 1921-1922, launched a campaign against foreign missions in Georgia, as examined in sequence here.

In 1921, following the occupation of Georgia, a difficult period began for diplomatic missions. Most of them left Georgia along with the Zhordania government, while those who stayed or returned later, to serve the economic interests of their countries, had to cooperate with the Bolshevik regime in Georgia, which, strangely enough, was considered the government of a sovereign country until December 1922 (before the official establishment of the Soviet Union).

In the first few months, the Georgian Bolsheviks—with figures like Budu Mdivani, Filipe Makharadze, and Alyosha Svanidze—maintained relatively normal relations with foreign representatives, as they needed these connections to bolster the authority of their nascent regime. Moscow even issued a special directive to treat the German representative, Ulrich Rauscher—the only high-ranking diplomat who remained in Georgia after the Bolshevik takeover—with respect. However, as the regime consolidated power, relations with Western missions deteriorated sharply.

The Georgian RevCom was irked by the activities of the Zhordania government-in-exile and the policy of non-recognition of the Bolshevik regime in Georgia. In the summer and autumn of 1921, members of the exiled government held meetings with German officials and demanded the withdrawal of Rauscher’s diplomatic mission from occupied Georgia, after which Rauscher and the Italian representative Franzoni were summoned to the residence of Svanidze, Commissar of Foreign Affairs of Georgia, who threatened to create problems if the Zhordania government stopped being perceived as the legitimate government of Georgia, and if relations with the Bolsheviks did not become formalized. Soon after, Svanidze’s deputy, Toroshelidze, publicly labeled Germany a hostile country and soon Rauscher had to leave Georgia for good.

From 1922 onwards, the Bolshevik regime’s punitive policies against foreign diplomatic missions escalated significantly. By targeting these foreign representations, the government sought to achieve multiple objectives. Primary among those was to secure international recognition of Georgia’s Soviet occupation, thereby undermining and delegitimizing the Zhordania government-in-exile. Simultaneously, the gradual reduction and eventual disappearance of foreign missions in Georgia was intended to weaken Georgian sovereignty further.

The Bolsheviks began to openly hunt down European diplomatic missions when their countries refused to recognize the Bolshevik regime in Georgia. On his return from Azerbaijan, the German ambassador Rauscher had his carriage forcibly removed from a train by members of the Extraordinary Commission (Cheka) on the pretext that he had no proper official documents.

The Bolsheviks also targeted Rauscher’s wife, preventing her from leaving Georgia by not allowing her to cross the border. Her luggage was humiliatingly discarded, and she was only allowed to depart three months later. German Consul Karl Cornelsen was expelled from Batumi, as was Danish Acting Consul Heinrich Warnecke, who, despite having lived in Batumi for 35 years and owning businesses, had his properties confiscated by the state. Representatives from the Netherlands, Belgium, Finland, Sweden, and Norway were all forced to leave Georgia. The Estonian representative was arrested in Baku along with his wife, transferred to Georgia, and expelled on charges of espionage. Meanwhile, the buildings of the Swiss and Dutch consulates were sealed, and the Cheka entered them to seize materials. Rauscher’s successor, Max Hesse, remarked in correspondence that his own arrest was quite predictable. After this wave of expulsions, the European diplomatic presence in Georgia comprised only the German and Italian missions.

The psychological terror inflicted by the Bolsheviks proved effective. The persecution of German mission in Georgia became a valuable tool through which Russian pressure was exerted during negotiations with the German government. Ultimately, in April 1922, Germany and Soviet Russia recognized each other under the Treaty of Rapallo, which helped Russia to break through from its international isolation.

In coordination with Moscow, the Georgian Bolsheviks eased the pressure on the German representation in Georgia immediately after the signing of the Rapallo Treaty. However, as the treaty did not extend to Georgia, the Georgian Bolshevik government remained unrecognized and still technically illegitimate.

In the summer of 1922, on instructions from Moscow, the Georgian Bolsheviks carried out another attack on the German mission. In July that year, the building of the German mission in Tbilisi was robbed and some documents were stolen. The robbery was orchestrated by the Cheka and executed by a former employee of the German mission, who had been recruited after his arrest for a separate crime in Moscow a few months earlier. According to his testimony, the Cheka had detained the German mission’s translator, von Norman, accusing him of anti-Soviet agitation, collaboration with the Zhordania government-in-exile, and espionage.

Deputy Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Toroshelidze, told Hesse that if the consulate had been official, the Cheka would not have dared to arrest von Norman, which was a direct indication of their demand to extend the Rapallo Treaty to include Georgia. The occupying authorities were trying to achieve this result via radical means. Hesse wrote that the orders to the Georgian Bolsheviks came directly from Russia, whose aim was to exclude foreign representations in Georgia as bodies bearing signs of Georgian independence, although it was meant to look as though this policy was that of the Georgians themselves.

In order to normalize the working situation, the German mission itself asked Berlin to speed up the extension of the Rapallo Treaty to encompass Georgia, as otherwise the mission would have to close down.

In September 2022, meetings between Hesse and Toroshelidze took place, culminating in von Norman’s release. However, he was soon expelled from Georgia. In return, the Bolsheviks achieved a significant success on 5 November 5 1922, when Germany officially extended the Treaty of Rapallo to include Russia’s satellite states, among them the Bolshevik regime in Tbilisi. This effectively stripped the exiled government in Berlin of its legal foundation. Shortly afterward, the Soviet Union was formally established, and the German representation in Georgia was transformed into the Consulate General in Tbilisi, which remained until the late 1930s.

A century later, modern Georgia has a government that mirrors the first-generation Bolsheviks in its disdain for Western representation, expressed both through hostile rhetoric and concrete actions. Like the early Bolsheviks, Ivanishvili’s regime directs its aggression toward missions from Western democratic states. Similarly, back in 1921-1922, the Bolsheviks allowed Turkish and Persian representatives to operate undisturbed in Tbilisi, while targeting European missions. This historic parallel can be linked to a shared authoritarian alignment, as Ivanishvili’s regime, much like the Bolsheviks, views law-based, civilized states as threats.

Furthermore, the Ivanishvili regime mirrors the first-generation Bolsheviks in its methods of dealing with the West. The former has repeatedly used a familiar Bolshevik tactic—first escalating tensions and then achieving its goals through minor concessions. A clear example of that is how the regime, with Western assistance, managed to bring the opposition into parliament following the latter’s boycott in the wake of an allegedly manipulated parliamentary election in 2020. This ultimately strengthened the anti-Western Ivanishvili regime, somewhat ironically courtesy of the participation of Western actors.

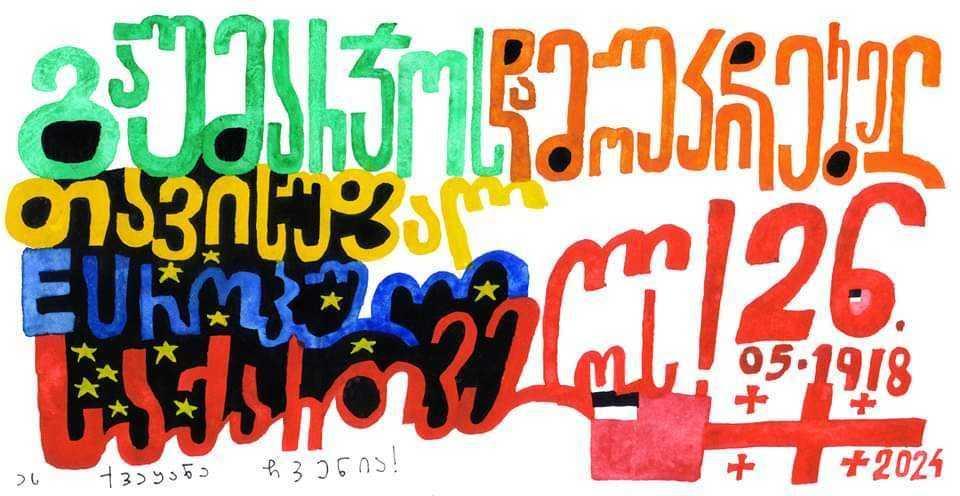

The management style and rhetoric of Ivanishvili, Irakli Kobakhidze, Shalva Papuashvili, Kakha Kaladze, and others is strikingly similar to the propaganda of the Bolshevik leaders Makharadze, Mdivani, Orakhelashvili, Toroshelidze, and others, who persistently claimed that a coup d’état was being plotted in Georgia with Western involvement. In 1922, the Bolsheviks even accused the German representation in Tbilisi of assisting the government-in-exile of planning a coup. In 2024, Ivanishvili’s cohort and their propaganda instruments/media similarly claim that a fictitious “Global War Party,” supposedly backed by the United States and the European Union, is attempting to orchestrate a revolution in Georgia to drag the country into war. The enemy image created by the Bolsheviks against the Zhordania government—which refused to surrender Georgia’s independence to Russia—has thus been rebranded in Ivanishvili’s propaganda as the so-called “collective national movement.” This term now targets not one specific party but rather all who oppose the establishment of a Russian-style dictatorship and the Russification of the country, which Ivanishvili formally announced on 29 April 2024.

In the eyes of the Ivanishvili regime, anyone who thinks differently is branded part of the “collective national movement” and labeled an agent of the West. Despite so many parallels, however, it’s worth noting one critical difference. In 1922, the Bolsheviks succeeded in expelling the West from Georgia, surrendering the country to Russian control for decades. This must not—and will not—be repeated in our time. The chance to prevent it is coming soon on 26 October 2024, when everyone who considers themselves a Georgian, a European, and/or simply a civilized person should affirm a resounding “Yes” to the democratic West and an unequivocal “No” to authoritarian Russia.