Author : Keti Kurdovanidze

A Story Told by a Friend

I was born in a seaside town. Anyone who is raised by the sea will know how spacious and immense that can feel. It seems particularly large when you are small when the kaleidoscope of other things and an unconscious longing for them has not yet been imprinted on your perception of life. Such things gradually fill your mind, eventually leaving no room for clarity or judgment. The contamination of this innocent seaside view with goods of different cultures and their costs creeps up on you so gradually and inexorably that you can only navigate through them, rather than appreciate them. Often, the perception of these goods exceeds their real value until one day fortune smiles upon you, and you discover the true price of such actual mediocrity. At that point, with a broken heart, you ponder how much emotion you have wasted on things you once considered valuable and exciting.

In my seaside town, where there were abundant exotic amusements, the most vivid and mysterious memory of my childhood is connected with the Soviet ethos, which was held an honorable place in the foyer of one of the polyclinics, reflecting the cultural heritage of that era, and somehow came to life despite being in stone form. I was very young then and did not even understand what the Soviet Union was and what its spirit or ideology meant. But my childish admiration for it touched my heart so much that when I saw the monument in the lobby, I thought that there could not be anything more beautiful in the world. So I thought anyway, and deep down I was proud that this apparently immortal masterpiece was right here, in my town, and not in Rome, Paris, or anywhere else.

As time passed, my life came to be filled with new impressions: Michelangelo Donatello, Bernini, Canova, Rodin, and Bourdelle slowly penetrated my thoughts, and that aforesaid childish admiration disappeared in the clouds of my memory like the setting sun in that seaside town, as if it had never existed.

Later, one day when I returned to visit my hometown, I found the same unworldly statue that had been etched in my memory on the floor of the polyclinic’s lobby, and now it appeared to me like a great and terrible monster - with a sickle and a hammer in its hands. A real Soviet ghoul, it now looked as pathetic as the dragon from Tolkien’s Hobbit and was a symbol of failed evil.

Osobtorg

You might be surprised, but my grandmother, who lived through the Soviet occupation of Georgia, repression, World War II, and even a coup d’état, never talked about anything as emotionally as she did about “Osobtorg,” - an economic system created in the 1940s, during the Stalinist era. It was supposed to ensure the welfare of the Soviet elite, while providing the proletariat with bread and other basic products through a voucher arrangement. Under “Osobtorg,” elite shops and restaurants were made available to Soviet generals and high-ranking officials who could access seemingly unlimited quantities of scarce products. Ordinary mortals were not even allowed to enter these stores, and could only look in wonder at the white bread and delicious cakes displayed in their windows, like they were museum exhibits. The specialness of these stores left a lasting and indelible impression on my grandmother, who had seen and experienced so much. However, in today’s reality, there was nothing in those stores that could compare to even a single shelf in modern markets. And yet the dreamy feeling stirred by their inaccessibility felt by my grandmother every time she passed by these stores back then, which she passed on to her grandchildren, was far more powerful and memorable than the thrill I later felt when experiencing a New York mall, where everything was accessible and all were free to enter. It is often the sense of inaccessibility that gives things and experiences a unique allure, especially in a closed, totalitarian system like that of the Stalinist era. In those times, the basic comforts enjoyed by much of the rest of humanity were available only to the regime’s loyal servants. Ordinary people, intimidated into silence, were left without them. They could only admire the “sweet life” of the ruling elite.

So many years have passed since the time of Stalinism and so much has been re-evaluated, yet some of its principles remain unchanged even in the post-Soviet era: “everything is fine, stay quiet, don’t question anything, just tolerate it.” After all, we should just accept that the chosen few political and artistic circles live carefree. These artists, athletes, and scientists earned your admiration and made you vote for the ruling party. Yet, they are the ones who consistently sold out and today sell out their homeland. It transpires that this so-called “elite” could neither withstand criticism nor face up to international competition. So, what’s left now for a tired, impoverished voter like my grandmother? Nothing. As she occasionally mutters at home: “There’s no government for the poor.”

The Dowry Suitcase

After the Stalinist era, when people finally felt able to breathe, a brown suitcase with iron corners and locks could be found in the pantry of nearly every middle-class family. Inside these suitcases were carefully stored bed linen, underwear, and towels, all of which had been acquired at great cost. These were often obtained through connections returning from Moscow, or purchased from speculators. Such items accumulated over the years became rare treasures, only to see the light of day if fate would smile upon their daughter for her to get married. Having such a suitcase allowed a housewife to sleep peacefully at night, knowing she was prepared for the future. During the day, she could enjoy the status of a caring parent, safe in the knowledge that the suitcase contained her most valuable possessions: lace nightgowns made in Germany, Chinese towels, kitchen towels with Polish designs, and a thousand other small prized possessions. In short, these were items that could only be bought “under the counter” in Soviet Georgia or after enduring long queues in the department stores of Russia.

All members of the family were forbidden to touch these suitcases (even elderly daughters, who remained spinsters), because the caring mother believed that she would never be able to have such a suitcase again, and that it could only be used for a special event such as marriage. In the minds of Soviet people, a daughter was only supposed to get married once, and that would last forever. Even though many things went out of fashion and faded, this particular tradition survived, and the fate of a Soviet bride was associated with that suitcase, even as it yellowed as it lay around for years unopened.

But the collapse of the USSR diminished the value of Czech crystal vases, once-expensive Arabic chandeliers that once held almost cult status, and even the alluring splendor of mass-produced jewelry from Russian factories. As time passed, it became clear that those vases were not worth anything, and nor were those chandeliers, while the Russian jewelry dwindled into nothing more than crude and tasteless accessories.

It was hard to come to terms with the crushing of the hopes these suitcases represented, but what could be done? At the very least, you could give them away and bring some happiness to those who had never tasted the alleged “sweetness” of Soviet prosperity. And so, homes gradually rid themselves of these unnecessary relics, with only mothball-filled German musical instruments and libraries of books, accumulated through coupons, remained.

Waste Paper

A Soviet person was not a “philistine” if they were not a book reader, as long as they were a book buyer. Books were hard to come by in the Soviet Union. There were three main reasons for that: censorship, limited resources, and a centralized bureaucratic publishing system. Book buyers tended to have a much better home library than readers, because in Soviet families such collections served not only an educational function, but also as an expression of the owner’s social status and an indicator of belonging to elite society. You might ask, what’s wrong with making a private library a marker of prestige? The answer is nothing at all. But in a country where books were scarce, a true reader would likely spend their time in a public library or go from door to door, asking to borrow books. Yet later, many books—never opened—ended up in the darkness of garbage bins. These were the books that Soviet people had acquired through connections, enriching resellers only to be displayed on shelves as a symbol of status. Most home libraries in Georgia back then were filled with books in Russian. In many households, you could find The Martyrdom of Saint Shushanik, The Life of Grigol Khandzteli, Aluda Ketelauri, and The Snake Eater—all published in Russian. If you asked the owner, they would have said that Georgian literature is enjoyable to read in any language. Yet, most of these books have been relegated to mere waste paper, unlikely to ever be read again.

Significant parts of such libraries were filled with bulky Russian-language multivolume works, which were a challenge not only to read, but also to store at home, especially in the cramped Khrushchev-era apartments. But a proud Georgian back then would rather sleep standing up and not buy a bed than deprive their bookshelf of the masterpieces of Seifulin, Fadeyev, or Ostrovsky. As a result, the homes of Soviet citizens were filled with what was essentially rubbish, all in the hope that their children would eventually read what they chose not to. However, it later became clear that not only did their children have no intention of reading these discolored books, but many of them couldn’t as they didn’t even know Russian.

The sadness of the useless dowry suitcases and the devaluation of the crystal vases et al. has nothing to do with what intellectual trauma inflicted on society. The legend of great Russian literature was shattered as the commonly used phrase ‘the literature of the enemy must be read in the language of the enemy” made way for the younger generation’s less compromising approach of “I will neither learn the language of the occupier nor embrace its culture.”

The general shame attributed to the ideologues who emerged from the artistic community during the Soviet era was felt acutely by Georgian society when the actors and artists they revered betrayed democratic principles recklessly and defended the interests of their occupiers. Whatever one might argue though, people still loved these figures, which made it difficult to come to terms with such a social failure. The admiration generated by the achievements of these talented artists, singers, writers, and sportsmen may seem unjustified in hindsight, but this is not easily erased from the heart.

The Sound and the Fury

Who would have thought that people disappointed by the Soviet reality—built on false values—and who had begun to embrace freedom would not learn and live by this lesson forever? Nevertheless, they failed to do so. Unfortunately, the collective memory of Georgians proved to be shorter than that of the Buendía family in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. The Georgians could not learn from their past mistakes or grasp their significance because the cultural and social failures of the Soviet era left their narrative fragmented and their emotions uncontrollable. Like the “idiot” in Macbeth’s monologue, or Benjy Compson, the mentally disabled character from William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, the country was left on the brink of reclaiming an alleged former glory while denying reality.

Thus, our lives became filled with sound and fury, especially as we once again face the danger of losing our independence. It took us a long time to see and recognize who and what we were really dealing with. And even when that became clear, we could not come together, understand the mistakes of the past, and develop a unified strategy for survival.

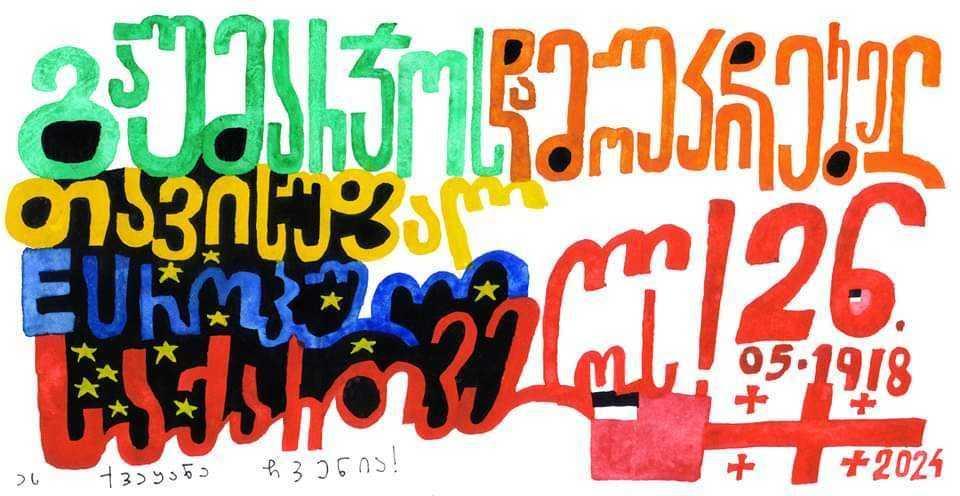

Despite the gloomy gravity of the situation, there is still a solution: on October 26, we must all take moral responsibility, show personal fortitude, and choose the path of change so that we never return to the era of dowry suitcases and never taste the bitterness of such disappointment again.