Author : Gigi Gigineishvili

The year 1993 began in Abkhazia with an unusual and blood-soaked coldness. After the slaughter of Georgians in Gagra in October 1992, the public learned every day about the horrifying details of the crimes committed in Gagra, Gantiadi, Leselidze, and other settlements by the Russians and separatists acting with their support. At that time, there were constant disputes and conflicts among the population of Abkhazia, but no one expected there would be such cruelty from their neighbors. A commission was set up in Tbilisi to investigate the fall of Gagra, although it was immediately clear that this would not bring any real results. After the Gagra genocide, there was substantial evidence that the Russian Federation was involved in the process, but the Georgian Investigative Commission, as well as numerous people in power in general, were not yet ready to call Russia an enemy or an occupier. This led to an unprecedented wave of anti-Chechen propaganda in the Georgian media, shifting the focus away from the Russian Federation’s actions. For context, during the entire war in Abkhazia, only around 350 Chechens sided with GRU agent Shamil Basayev. The majority of Chechen fighters refused to join the Russian army to fight against Georgia in Abkhazia (barely one-third of the number of Adyghe who joined the fight). However, the Georgian political elite, unwilling to criticize Russia and keen to discredit Zviad Gamsakhurdia (who was in exile in Grozny at the time), directed blame toward the Chechens. Absurd claims circulated, alleging that “the Chechens declared a holy war—jihad—against Georgia” or that “5,000 Chechens were sent into Abkhazia,” and so forth.

In December 1992, a Russian Defense Ministry helicopter was shot down in the vicinity of Tkvarcheli, near the village of Lata, in Georgian-controlled territory. A great tragedy ensued, in which innocent women and children, including those from mixed Georgian-Abkhazian families, lost their lives. According to an agreement, the Russian helicopter flying from Tkvarcheli to Gudauta had to pass through Georgian-controlled territory in Sukhumi and then continue to Gudauta. The Russian crew of the helicopter deliberately violated the agreement, taking on board 12 armed militants and promising to “sneak” them through the Kodori Gorge to Gudauta. As a result, the Russian military helicopter - a legitimate target - was shot down near the village of Lata by people whose identity is still unknown.

The Abkhazians called this flight a “humanitarian flight,” and along with the women and children lost, they also wept bitterly for the Russian and Abkhazian fighters killed in the same helicopter. This incident has never been fully investigated, giving the Russian-Abkhazian side an opportunity to use the issue to propagate hatred against Georgians.

Albert Topolyan

Albert Topolyan

The Gagra genocide and the Lata tragedy brought an unprecedented level of cruelty to the clashes in Abkhazia. On New Year’s Day in 1993, Abkhazian forces twice attempted to invade Sukhumi, but were thwarted, losing about a hundred fighters. Desperate for reinforcements, the Abkhazians appealed to Russian forces. In late January 1993, Russian generals began preparations for an attack on Sukhumi. On February 9, a battalion named after Bagramyan was formed in Abkhazia, led by Albert Topolyan, an agent of the Russian special services.

The battalion comprised a total of 1,500 men and was financed by a group of businessmen of Armenian origin working in Russia. In addition to Armenians living in Abkhazia, the battalion’s ranks included both Karabakh and Armenian fighters. It fought mainly under the Armenian national flag and was particularly brutal against the peaceful Georgian population.

Warriors of Bagramyan Battalion

Warriors of Bagramyan Battalion

In September 1992, the Russian Federation had issued its final verdict on Georgia regarding Abkhazia. As a result, Russian bases and generals stationed throughout Georgia and the entire Caucasus, especially Viktor Sorokin and Alexander Chindarov (who were in the inner circle of Russian Defense Minister Pavel Grachev), had already openly engaged in punitive measures against Georgia.

Specifically, for this operation, the Russian-Abkhazian units fighting in Abkhazia received an additional four units of “Grad” equipment, 15 units of infantry fighting vehicles, up to ten D-44 cannons, and a large quantity of 120mm and 82mm grenade launchers, machine guns, large quantities of automatic fire weapons, communications equipment, special means for forcing the river, and equipped medical vehicles.

Colonel-General Alexander Chindarov (Deputy Commander of the Airborne Forces of the Russian Federation, awarded the title of “Hero of Abkhazia”;

according to the official Russian version, he was engaged in peacekeeping activities in Abkhazia) and Vladislav Ardzinba.

The active involvement of the Russian Federation and the harsh measures against Georgia were personally led by the Secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation, Yuri Skokov, about whom the Georgian public had less information. He was the main initiator of a multi-stage plan to wrest Abkhazia from Georgia. Apart from Skokov, separatist leaders were in active personal telephone contact with the President of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin, and had several personal audiences with him during the year-long war.

By order of the Russian general Chindarov, the development of a plan of attack on Sukhumi was entrusted to the headquarters of the Russian base in Gudauta and to Sultan Sosnaliev (a colonel of the Russian Federation, who was appointed the so-called Minister of Defense of Abkhazia on the recommendation of the GRU). The plan was devised by Russian officers and then presented to the Abkhazians, who formally approved the plan and agreed to everything. In addition to the transfer of weapons, officers of the Russian Parachute Regiment N345 from Gudauta trained the Abkhazian fighters on the Bzyb River, in the vicinity of the Gagra zone.

Pavel Grachov, Yuri Skokov, and Yevgeny Primakov

Pavel Grachov, Yuri Skokov, and Yevgeny Primakov

On 13 March 1993, the whole of Sukhumi was gripped by the news that a major attack on Georgian positions was being prepared from the right bank of the Gumista River. In response, Eduard Shevardnadze and most of the Cabinet of Ministers became personally involved in organizing the defensive line.

At dawn on 14 March, the Russian Air Force dropped 49 units of 500-kg bombs along the entire perimeter of the Gumista River frontline, close to the Georgian defensive line, all timed to detonate at 00:05 on 16 March to signal the beginning of the attack on Sukhumi. However, for unknown reasons, not a single bomb exploded at the appointed time, causing some confusion in the enemy camp. The start of the assault was postponed because the separatists, who were supposed to go on the offensive, worried they could be killed by their own bombs. The Russian generals said that the bombs would be deliberately set off, but that failed too, leading to disagreements between the Russian and Abkhazian fighters. The so-called Chief of the Abkhaz General Staff, Sergei Dbari, refused to launch an attack, supported by other Abkhaz commanders. Russian generals were able to convince the Abkhazian fighters that this was the ideal moment for a successful assault and that they would not be given such a chance again. They also promised that the Russian Ministry of Defense would compensate for the unexploded bombs with massive air strikes and that additional artillery would be especially powerful. Ultimately, the Abkhazians agreed. At 03:00 in the morning, a furious attack on the Georgian positions began, starting from the Black Sea side and ending at the upper road bridge over the Gumista River (in the direction of Achadar), covering a total stretch of 10 kilometers.

March 1993, Bzyb River.

March 1993, Bzyb River.

The Russian Air Force attacked with unprecedented intensity and for the first time used so-called “military garlands,” which illuminated the Georgian positions in the middle of the night. This was also a novelty and a surprise for the Georgian defensive line, as most of the Georgian fighters were not professionally trained.

At 04:00, intense artillery bombardment of Georgian positions and residential neighborhoods began, carried out by the Pskov Division. The scale of this assault was unprecedented: around 20 pieces of artillery equipment of various types fired continuously for about an hour. This battle, one of the largest in modern Georgian history, contained an element of tragicomedy. Officers from the Russian Airborne Combat Battalion No. 901, stationed in Sukhumi’s Shukur district, were officially there to ensure the city’s security. Yet, quietly, they assisted in adjusting artillery fire on Georgian positions across the Gumista River, relaying information to the Pskov artillerymen. These same officers, who had fostered friendly relations with the local Georgian population ultimately facilitated the destruction of Georgian lives.

Gumista Bridge and the railway bridge

Gumista Bridge and the railway bridge

In addition, the Tbilisi base of the Transcaucasian Military District (ZAKVO) provided logistical support to this conflict in Abkhazia, naturally against Georgian forces, even though they were reputed “supporters” of the region.

The plan of attack also included the landing of fighters from the sea, in the area of the Kelasuri River in the Bay of Sukhumi. To this end, at 03:00, five small boats left the port of Gudauti, heading towards the rear of the Georgian positions.

At 05:00, it was the turn of the Russian-Abkhazian infantry units, composed of Russian regular army officers, including fighters from the Russian Army’s Airborne Combat Regiment No. 365, the “Tapir” group, the Cossack group, the Slavic battalion, the newly formed “Bagramyan” Battalion, the Chechen group, the Confederate battalion, and units named “Katran,” “Berkut,” “Eucalypt,” “Grad,” as well as Russian riot police from Riga.

Although the Georgian armed forces were on alert for an attack, the sheer scale of the assault allowed was overwhelming. Hundreds of fighters penetrated the Georgian frontline, advancing in the north near Gumista Bridge, close to the village of Achadar (previously demined by Russian special forces), and in the center, where they crossed the river at a railway bridge and two other locations.

Hand-to-hand combat erupted in the trenches in several areas, and the enemy appeared in another section of Sukhumi. Amid the ensuing chaos, Georgian fighters wrapped white bandages around their left arms to distinguish themselves from their foes.

March 16, 1993, Gumisti Line

March 16, 1993, Gumisti Line

Aviation chandelier

Aviation chandelier

According to the overall plan, five boats departing from Gudauta Port entered the Bay of Sukhumi undetected by 06:00 and proceeded toward Kelasuri River. By sheer chance, artillerymen from the “White Eagle” battalion stationed in Agudzera—specifically Officer Aleksandre Papashvili and his team—spotted them. Without formal orders and acting on their own initiative, Papashvili’s unit, which had been sent to the rear for artillery maintenance, opened fire using partially disassembled artillery installations. Within minutes, the Georgian artillerymen managed to sink two boats and damage a third, forcing the remaining two to change course and return to Gudauta. The Russians’ plan to land forces behind Georgian lines failed on this occasion, though they would successfully execute a similar maneuver months later during the so-called Tamish landing.

The most intense fighting took place on the Gumista front, where Russian and Abkhazian units advancing on Georgian positions were met by Georgian artillery under the command of Colonel Temur Lomtatidze and Colonel Emzar Chochua. From early morning, they launched strikes across the Gumista River toward enemy reserves and firing points on the right bank. Within hours, they had destroyed seven trucks loaded with fighters and weaponry, five armored vehicles, and multiple artillery positions. With several precise shots, they eliminated Russian fighters who, in a panic, attempted to find new cover—only to be effectively targeted by Georgian artillery, even in their new positions. By March 16 at around 02:00, the separatist formations on the right bank of the Gumista (under Russian control) were in a far more difficult position than those attacking on the left bank.

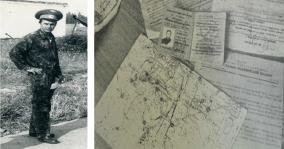

Russian Federation’s Major V. Shipko and his identity documents

Russian Federation’s Major V. Shipko and his identity documents

As a result, the enemy’s assault groups were left without a rear, halting their advance. This development ultimately determined the outcome of the battle. Facing heavy losses and with reinforcements failing to arrive, the Russian-Abkhazian forces decided to retreat by the afternoon. By that time, Georgian units had consolidated their positions, stabilized the frontline, and obtained precise information about enemy locations. As the retreating forces came under intense Georgian fire, they suffered devastating losses—the heaviest during the entire conflict. Significantly, the separatist forces sustained their greatest casualties while attempting their own offensive. Chaos abounded among the enemy ranks.

The Russian-Abkhazian artillery fired erratically, and many Abkhazian fighters reported being struck multiple times by their own artillery bombardment on the left bank of the Gumista. By the evening of March 16, the fighting had subsided, though small skirmishes with isolated enemy groups on the left bank of the Gumista continued until March 18. Active hostilities came to a halt on March 19, when Georgian military forces shot down Russian Air Force SU-27 fighter jet, serial number #11, near Sukhumi. The aircraft, piloted by Major Vatslav Shipko, had been targeting both combat positions and populated areas using typical Russian bombardment tactics.

Russian SU-27 in the sky over Sukhumi

Russian SU-27 in the sky over Sukhumi

The officer had various documents with him and was found dead in the plane’s cockpit by Georgian law enforcement personnel, who handed his body over to the Russian side after completing investigative procedures. This incident provided the first indisputable and historic evidence of Russian involvement that the Georgian side had obtained since the start of the conflict. For much of the Georgian political elite of that time, this evidence posed a profound moral and psychological dilemma. Despite opposition from his team, Shevardnadze visited the crash site in the high mountains near Sukhumi, accompanied by Georgian and foreign journalists, and ordered that the incident be publicly reported.

Within days, photos and videos of the downed Russian military plane spread worldwide. As a result, from 19 March 1993, the so-called “brothers in faith” once again became, in the eyes of many previously hesitant Georgians, the embodiment of a bloodthirsty and ruthless enemy.

This battle clarified three key points for the Russians and Abkhazians. First, from a purely tactical standpoint, a direct assault on Sukhumi from the Gumista was unfeasible. Second, despite chaos and resource shortages, the Georgians had shown the ability to unite and concentrate their forces during critical moments. This meant that for the separatists to succeed, mere arms deliveries would be insufficient; they would need to replicate a strategy similar to the seizure of Gagra—signing a peace agreement only to break it at a strategically opportune moment, following a well-worn Russian approach.

Historically, the Russian-Abkhazian side used this method repeatedly. They seized the Gagra zone by violating the peace agreement of 3 September 1992, occupied the northern heights of Sukhumi, Shroma, and Kamani, breaching the agreement of 14 May 1993, and finally captured Sukhumi, Ochamchire, and Gali, disregarding the 27 July 1993 agreement.

The third revelation here was the exceptional accuracy of the Georgian artillery, which consistently won duels despite the adversary’s superior and more numerous weaponry. This effectiveness likely influenced the terms of the 27 July 1993 peace agreement, under which Georgian artillery installations were to be stationed in the Gulripsh district. Yet, for reasons still unknown, Russian generals moved these artillery units far from Abkhazia—to Poti—using their own ships. This relocation warrants thorough investigation by the Georgian state.

In recent years, more than a hundred Russian-Abkhazian books have been published describing the triumphant military actions of the so-called Abkhazian army. For example, there are tales of how an Abkhazian group of 250 men defeated a 5,000-strong Georgian unit in Gagra, and how 1,200 Abkhazian fighters defeated 25,000 Georgian soldiers in Sukhumi. However, these works ignore the fact that Georgian combat-ready units and artillery were withdrawn from Abkhazia at that time due to the peace agreement, and their “congenial” attacks ended before the peace agreement was signed, as can be seen from this article and other sources of information available in abundance.

In the end, the Russian-Abkhazian side lost about 500 fighters in the battles near the Gumista on 16-19 March, and about a hundred fighters were captured by the Georgian side. In order to quell the panic caused by the heavy losses, the separatist propaganda media officially announced an easy-to-remember and reduced/falsified figure of 222 casualties, and to this day the number 222 is mentioned and disseminated in their articles and documents. However, the Abkhazians themselves are well aware that this figure does not correspond to the real losses. Unfortunately, the March 1993 clashes also resulted in heavy losses on the Georgian side: 135 fighters and about 40 civilians were killed in the treacherous attack on Sukhumi. Many buildings were damaged and destroyed during the conflict; today, Abkhazian tourist guides often showcase these ruins to tourists as examples of supposed Georgian brutality. The military operation bears resemblance to the Battle of Aspindza, led by Erekle II, who was betrayed by the Russians. In that battle, Erekle allowed half of the Ottoman army to cross the Mtkvari River before blockading and damaging the bridge, ultimately destroying the forces that had crossed first, and then slaughtering those that remained on the opposite bank.

On 19 March 1993, the enemy fled the battlefield. The excitement of the Georgians in Sukhumi knew no bounds, but the danger was still truly great. Volunteers from all over Georgia gathered in Sukhumi, and a big counterattack was planned. There was hope that it would all be over soon, but Gudauta was gripped by extreme sadness and hopelessness. Vladislav Ardzinba was so depressed that he almost committed suicide. The situation proved a turning point, but despite the expectations and categorical demands of the Georgian fighters, for unknown reasons a counterattack on Gudauti was not carried out. This decision naturally led to significant dissatisfaction, prompting plans for military operations aimed not at Gudauta, but at Tkvarcheli. Preparations were underway, with artillery units navigating challenging terrain to occupy the area surrounding Tkvarcheli. However, on 20 March 1993, at 07:40, they received orders to turn back. The Georgian fighters were taken aback, as the instruction was unequivocal: “There will be no more attacks!” This development remains cloaked in mystery. Some assert that the counterattack was called off due to threats from high-ranking Russian officials, while others attribute the decision to the army’s lack of preparedness. Regardless of the reasons, it is undeniable that during that critical period, Georgia lost its most significant opportunity to bring the ongoing military campaign in Abkhazia to a victorious conclusion. Choosing not to go on the offensive at that time was both a grave mistake and a crime, the consequences of which became apparent just six months later, in September 1993.