Author : Zaza Bibilashvili

I turned 50 in August - a no-nonsense age, as people often say. Those five decades I have lived might as well represent several 50-year lives, each radically different from the other. My mind hasn’t fully absorbed the weight of this number, but from an outsider’s perspective, the only event in which someone my age is still called “young” is death: if he were to pass away at 50, people would say: “What a shame, he was so young.” So you have to cultivate a youthful disposition, in the hope that it remains at least somewhat compatible with the reality of time.

More than anything, it’s the age of my children that reminds me I’m no longer 30 or 35. I say this as if 35 years weren’t already a substantial stretch. After all, God took even younger souls—Mozart, Schubert, Baratashvili, Alexander the Great, a whole cohort of rock stars, and even His only son. When their time came, each had already made their mark. Yet here in Georgia, many 35-year-olds are still regarded as “talented, promising youth.”

Indeed, some release the cosmic energy invested in them early on, while others journey into old age before bringing to light the “ore” they’ve mined in their life’s travels. What youthful passion of Werther could rival the profound eroticism in Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs, composed at age 84? Goethe completed Faust at 82. Before that, at 72, he fell head over heels for 17-year-old Ulrike von Levetzow (he would have married her, had it not been for her mother’s firm position). Mark Twain and Charles Darwin were both in their fifties when they published their defining works.

But sometimes a late death can be as tragic as an early one. Imagine an elderly Don Giovanni, who settled down, stopped womanizing, and got married. Or Isolde, who, after mourning Tristan, surrendered to fate and wed King Marke, or an aged Amadeus, despite having long ago mourned himself with the first bars of Lacrimosa, still composing popular pieces for the emperor’s praise simply to make a living. What would Christ’s life have meant if he hadn’t been crucified? Can you picture an elderly Nazarene, weary from wandering and preaching, handing over his mission to his disciples and retiring to tend cattle and raise grandchildren? Rossini, sensing he had nothing left to say, retired at 37 and lived another 40 years without writing another piece…

A few years ago, sitting at a Georgian supra, I confessed to a new friend made through wine, that I felt as though I’d accomplished nothing in my life. Perhaps my father was to be blamed for this unreasonable standard. When I turned 16, he asked me: “What are you doing? At your age, David Agmashenebeli was already a king.” Years later, I found my moment to retort. When he turned 69, I said: “Now don’t tell me, ‘I’ve done my job’ and ‘the future is yours’—Reagan was elected president for the first time at your age.”

So, as I was telling you, I opened my heart to someone beside me at the table – “I’m 30 years old and I haven’t left any mark on this world”. He chuckled, seemingly satisfied with his own achievements, and gave me an arrogant look. Or maybe he did nothing of the sort, and it only seemed that way to me, thanks to the wine. One way or another, what I meant to say is that we each have something to accomplish in this world. “Success” and “happiness” can’t be the real goals. There is something else — something far greater — than mere “success” and “happiness”.

* * *

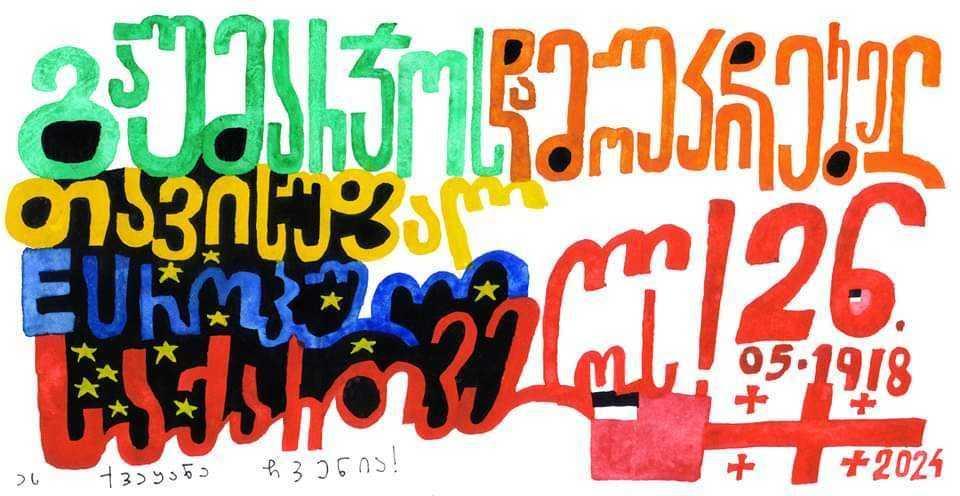

It was back when the Iron Curtain still split the European continent, and the Berlin Wall stood guarded by Russian occupiers, that fate sent me and a group of Georgian students to study in the US. Like Sacha Baron Cohen’s character Borat, we were scarcely prepared to meet the free world. Even the English I thought I knew (gleaned from the finest Soviet textbooks) turned out not to be of any use, and I had to start from scratch. Just when I was supposed to be entering the “street academy,” the Lord dropped me into the heart of “rotten capitalism,” exposing me to every social extreme in a short time: I lived in abject poverty in a Black ghetto and learned the decadent luxuries of the wealthy (indeed, I learned and embraced them so naturally, you’d think my grandfather had died from swallowing snails on Avenue Montaigne). I internalized the harsh rules of a public school that felt like a prison for repeat offenders, and in a liberal private school reminiscent of Platonic Academy I made invaluable friends, most of whom were second-generation immigrants. Recalling these stories and capturing the real, unvarnished Soviet Union, and what we imagined America to be versus the reality we encountered, as well as the emotional and tectonic civilizational shifts that unfolded against the backdrop of the final years of the Cold War, will soon be crystallized in a published book. But before that, I’d like to share three key lessons that three ordinary Americans taught me in that almost immemorial past.

1. Tom Kent, Sr.

Tom Kent was born in 1923 in a remote village of a remote county in Mississippi, America’s Deep South. His childhood and adolescence coincided with the years of the Great Depression. Little Tom’s life was a never-ending labor: he would wake up and be on his feet at five in the morning. First he delivered newspapers, and then he’d go to school. Then he would help his father pick potatoes, followed by homework. At the end of the day, he would fall asleep exhausted, only to repeat the same routine the next morning.

Tom Kent grew up in extreme poverty. He had no “patron” or well-wisher to lend him a hand. To his family, he was more of a laborer than a child to care for. This went on for years, decades, and even whole eras until, one fine day, he became the chairman of the board of a large insurance company. By the time I met him, he was already retired. Almost by chance, he took me along one day to his former company, perhaps wanting to show off some of his past glories.

We would jog together in the park on Saturdays. Even though he was half a century older than me, he never lagged behind or stopped. He’d run three miles without breaking stride, and occasionally he’d mutter: “Don’t talk while running; breathe smoothly!”.

I hadn’t known anything about his childhood when, after one of our runs, I sat beside him on a bench, clutching a water bottle, and told him that Georgia had always been a country surrounded by enemies, poor but inhabited by kind and hospitable people—a country that seemed forever unlucky, never graced by fortune. Luck, I explained, had no mercy, and so freedom and prosperity remained an unattainable dream, generation after generation.

Tom wiped his forehead with his cuff, put the cap on his water bottle and said:

“Remember, son, poorness is a state of mind - you may not have a cent in your pocket, your shoes may be tattered, you may even be hungry, but you are ‘poor’ only if you come to terms with the situation, accept it as a given and stop fighting to win.”

This was my first American lesson: that both victory and defeat are born in our minds.

2. Michael Moore

Carrie was a beautiful Irish-American girl, from an exemplary Catholic family with five children. She was so stunning that for a long time I didn’t dare approach her. Instead, I’d tease her during classes, like a third grader, unable to express my admiration in any other way. Later, much to my delight, she admitted to me: “I used to complain to my mother every day: there’s a boy in my class who won’t leave me alone; he keeps needling me.”

When Carrie agreed to go on a date, I was at a loss and did not know how to react. I had expected a rejection and was preparing for sadness, accompanied by my favorite love poems “The farther you are - the sweeter this gets!,” “You Were Married That Night, Mary!” and so on. Carrie turned out to be an ordinary girl. More earthy than ordinary, she was visibly tired of being held captive by her own beauty.

Soon after, like a true Catholic, she invited me to a family dinner and took me to her house, where she introduced me to her four brothers, her mother and her father. The brothers immediately began testing me and setting me up. Carrie’s father did not pick on me. He was a big, loud man. Michael Moore began by telling me his family history - he knew who they were before they had left Ireland. Then, he went into uninteresting detail and told me briefly about himself: “I sell life insurance”.

What he said left me cold; it didn’t inspire me. I couldn’t keep the conversation going, not even out of politeness. I had nothing to add to his story—neither surprise nor admiration. So, with my then Georgian idealism, I said: “I can’t sell anything, and I don’t want to. I want a life or career where that’s not necessary.” I looked down at him from the same mental pedestal from which the rather tipsy man sitting next to me at the table was looking down at me when he said: “I’ve already achieved a lot in my life.”

Mike gave me a paternal smile and remarked: “Listen, son, in a free country we all sell something: an idea, knowledge, a skill, a craft, a thing, or a service. So get off your pedestal. My wife has cooked a great meal, and it’s getting cold. I’ll tell you the rest at the table.”

It was then that I realized for the first time that selling something – a disgrace according to a retrograde Georgia tradition – is not a shameful at all, despite what we were taught at school and are still being taught today, and that craftsmanship is not a niche for ‘foreigners,’ which is deemed beneath the dignity of the average Georgian. After all, in the modern world we are all constantly selling something. It was trade and craftsmanship that made the West what it is, bringing wealth and prosperity. However, trade is still looked down upon in Georgia. We trade and sell “with two diplomas” – implying that we have to, not because we choose to. If luck were on our side, we would be princes (not even mere nobles!), sitting with our legs crossed, as would befit a dignified nation with three thousand years of cultural heritage. And though fortune has not smiled on us, this desire to sit back remains the root of our quiet existence, marked by a deep-seated fear and a desire to fit in.

That night, I couldn’t shake this thought, which gradually turned into a lesson: in reality, we are constantly selling something. Once one internalizes this notion, many things change. “I’ll sell ideas,” I thought to myself, still sitting on my pedestal. Over time, I became convinced that nothing brings greater pleasure than when your words travel far and wide, crossing “nine mountains and nine seas” only to return to you from someone else.

3. Bob Stafford

Bob Stafford was an old-fashioned Southern man, who had married the much younger Vicki as his second wife. A small business he’d started years ago was well organized did not take up much of his time. The family had two dogs: Bubba, a big, sweet, chubby black Labrador; and Pete, a scrappy mixed breed rescued from a dump with his tail perpetually sticking up. Pete was known for his rude behavior and utter disrespect for Bob’s guests with no trace of gratitude for being salvaged and welcomed into a paradise, where he even shared food from their plates instead of scraps.

Bob had a cozy house with a large, beautiful estate, scattered bushes, and flowers along the lakeshore. He enjoyed lying in his hammock, cracking open beer cans, chasing the dogs out of the lake and back to the yard, and barbecuing on Sundays. He also loved to hunt and had several hunting rifles. Once a month, he would put Pete and Bubba in the trunk of his old pickup truck and go hunting. He usually came back empty handed, but that didn’t matter, because it was more of a ritual of walking the dogs and male bonding with his son than a real hobby. His son, Scott, was much older than me and a somewhat unstable of a guy – always looking for work, but not too actively, like a true Georgian.

We often visited Bob and Vicki as the latter was our study coordinator and took on many mothering and mentoring roles.

I had just learned to play pool. Well, saying I had “learned” was a bit of a stretch. I’d say I knew the basics and played now and then. My favorite moment here was when the balls lined up in front of the pocket. I would aim carefully, strike with all my strength, and, often, even a well-aimed shot would bounce off the pocket walls and roll back. Watching this struggle, Bob eventually couldn’t hold back. He took off his glasses, which had already slid halfway down his nose, and slowly, with a heavy Southern drawl, addressed me (fortunately, there were only two of us there at that moment):

“Son, I hope you’re not like that in bed!”

I thought to myself, had Uncle Bob forgotten my age? Not only “not like that” – I was not like anything in bed yet, but thanks for the advice, I thought, I’ll definitely keep it in mind for the future. Since then, his words have stayed with me, surfacing in all kinds of contexts, formulating as a third lesson:

“Don’t be in a rush! Take your time and measure carefully! For every victory is victory is born in one’s mind.”