Author : Guga Sulkhanishvili

On Mtatsminda, a young man met his tragic end not long ago. Multiple rounds were used to take his life. But does it really matter how many shots were fired? The conflict started in some entertainment establishments and so ended.

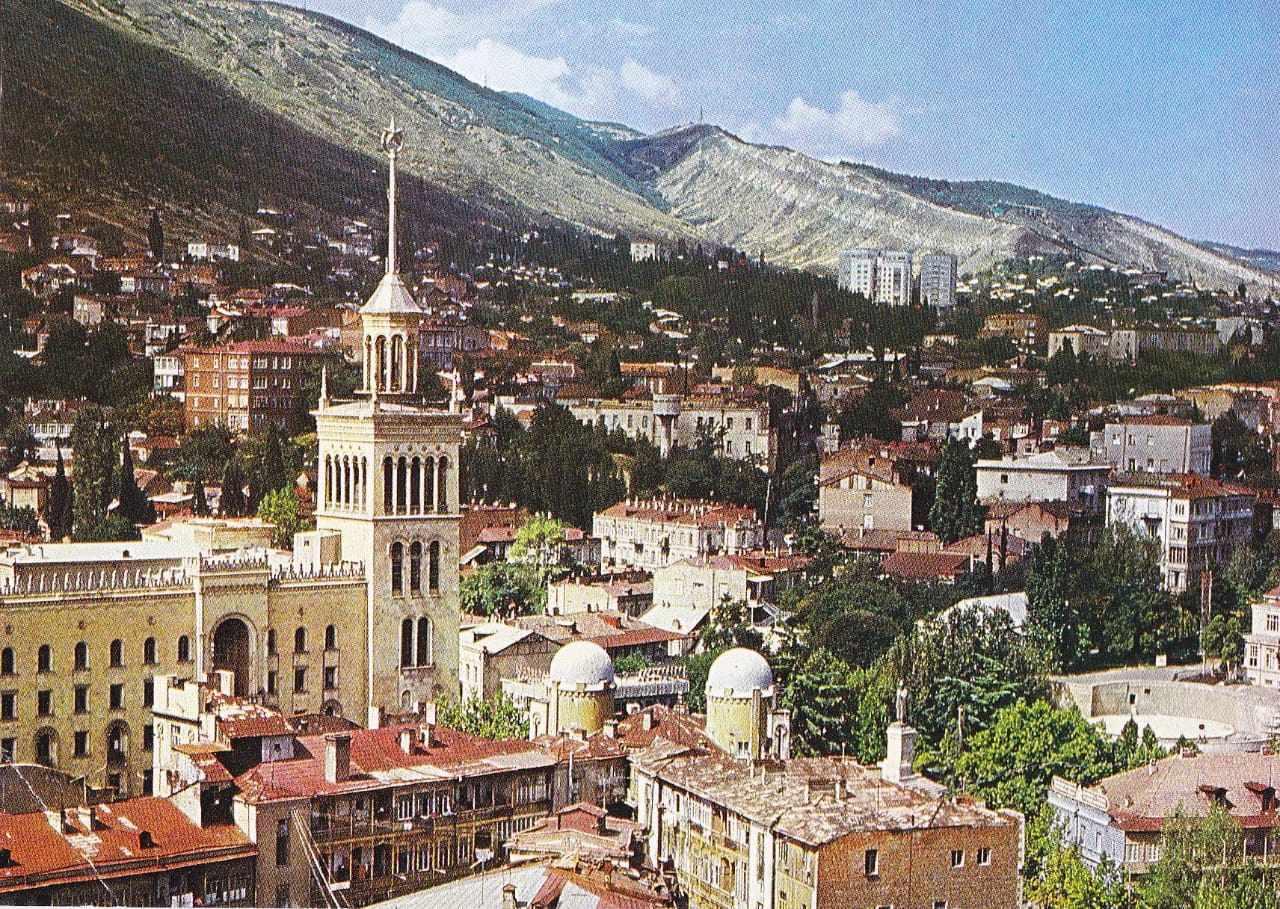

I was probably about 6-7 years old when I received permission from my family members to go to the schoolyard on my own. The school and its yard, where there was a football field, were about 50-60 meters from our house. The beautiful old red brick building of the Russian school was clearly visible from our windows, but the yard and the stadium were further away, and since they were out of sight, my parents were not very eager to let me go there.

Getting permission meant that my football passion and talent (I say this ironically, of course) went beyond the confines of our apartment and the Italian courtyard. Instead of playing one-on-one with my neighbour Vakho, I got the opportunity to participate in big, real football games. But that wasn’t even the main thing: Away from the insistent gaze of my parents, I could endlessly nibble sunflower seeds, chew gum, and after a football match, drink as much tarragon lemonade as I wanted; pull out of my subconscious a lot of accumulated four-letter words that were inappropriate for my age and use them up; shamelessly stare at the Russian-school girls with white bows and dresses that were unusually short for a Georgian school; and communicate with people. Because the schoolyard, the football field, was a meeting place for all kinds of people: neighbourhood boys of all ages, the superintendent in a dingy jacket with a folder and his assistants, plumbers and electricians who had finished their work, drunkards, taxi drivers who came in to pee. And, of course, street boys.

The term ‘old man’ became known to me around the age of 10 or 11, and ‘good boy’ even later. Before that, they were all known to me as ‘street boys’.

You would definitely recognize the street boy as a street boy. He wanted you to know his status, and that’s why. Apart from the fact that they swore the most, and threw their school bag the most carelessly, there was something unkind in their actions, some artificial manner. They even played football differently: During a yard game not for life, but for death, you didn’t remember anything else.

It was a World Cup final and a league final, but not for street boys. Their manner of play or pathos expressed that soccer is secondary, it was something else that mattered. And that something else was himself. Him—a street boy. For example, in the middle of a game, he might grab the ball, kick it with his foot, and throw it over the fence. Just to ruin the game, and he would laugh out loud about it, or he would start dribbling the ball pointlessly, or he would start a serious conversation with a guy standing on the sidelines, and when someone would tell him to get back in the game, he would yell angrily, ‘Don’t you see, I’m talking!!!!’

There was another nuance. Despite my great resistance, I was often put in the gate as the youngest. During the heated game, there were some tough hits from the adults and teenagers as well. The author of the ‘batted strike’ would definitely say to me: ‘Wow, Guga, I forgot it was you standing there’. Or ‘Did you hurt your arm, boy?’ It didn’t mean I wouldn’t get hit harder in a minute, but it was part of polite backyard football etiquette. And everyone did it, except the street boys. They lacked empathy.

After the game, we would all sit down either on the remains of old desks thrown out of school or right on the curbs. The street boy was sure to be in the centre. There the sermon would begin: what the right answer was, what to say in what cases, where you can kiss a woman and where not, how to respond to an insult, what harm masturbation does to a person, and most importantly, spitting. This amazing, unique, real Tbilisi spitting. Puffing up the cheeks and spitting like a shot from an air pistol. And the preacher sitting in the middle of this spit pond. Every man has spat in his life, but this amazing spitting show was arranged precisely to emphasize their uniqueness.

They would also tell criminal and semi-criminal stories. ‘I injured someone, took something from him, stole a battery from someone, broke into a store and took so much champagne.’ One day, I looked around and, despite my age, I had enough brains to realize: If so many people around us now knew these stories, how come the police didn’t know? I asked directly: ‘Do the police know?’ If they did, I would be in jail. ‘And if one of you tells them,’ he said, ‘I will kill you.’

They knew it, they knew it for sure. They knew it then and they know it now, in our time. And whoever they don’t know about in advance really ends up in prison. I would have been about 10-11 years old when I was finally convinced of my findings: There were some really outstanding old boys gathered in front of our school building. They were last graders. I crossed the street and headed home. I don’t know what exactly happened, but one of the old boys cursed at a passing taxi driver. I turned around at this swearing. The taxicab braked abruptly, the driver got out of the car and started calling the one who was cursing a rascal. The rascal slowly moved towards the driver, took a knife out of his pocket, and stabbed the driver. The driver ran away. The rascal’s friends didn’t even move, they were so sure of their friend’s success. The worst part of the whole story was that the school principal (I deliberately don’t want to write his name) was watching the scene from the balcony. ‘...What are you doing! Shame on you! Immediately enter the school!’. And what kind of principal was that, you know? If you didn’t have your pioneer tie tied properly, he would drag you into his office and scold you. He called the police because of a fight between fourth graders. And here a guy in broad daylight, in front of everyone, stabbed a man and this principal of ours calls him with tenderness in his voice, saying, ‘How are you not ashamed?’ And nothing else! He didn’t even call the police.

In a country like ours, criminals have a very hard time if they don’t cooperate with the government and have its support. Cooperating and turning a blind eye to petty criminals is a Soviet tradition. This tradition has spawned a sub-tradition of ‘old boys’, the legends and myths of street school and romance. But the thing is, no one runs up and kills a person directly (with very few exceptions). Murder is preceded by petty and medium crimes. No, we’re not experts, but you don’t have to be an expert. It’s the most basic logic.

‘Zero Tolerance! Everybody to jail!’ You can’t argue, it’s a terrible phrase. I don’t need to remind you who and what era it belongs to. But the author of this phrase, due to his fervour or emotional background, missed the main word: ‘All criminals to jail!’ Yes, if we want a Western-style liberal-democratic state, as they sometimes say, then all criminals, big and small, should serve their due punishment. And many lives will be saved.

And yet, why are there so many murders? The answer lies in our environment. The criminals who have taken the thorny path have become very successful people. I mean from a material point of view, of course. So that way is the way to success in this country. And murder is a way to enter that path, a way to open the door in that sphere. From what I’ve heard about murder, 99% of the time it’s not some unresolved problem where the only way to preserve your dignity is to kill somebody. Murder is a statement written in gold letters on the resume of the perpetrator. But what do you do when you graduate from Harvard or Yale and are looking for a job?

Solution? Let us first remember that before the 2003 elections, for years the government had been assuring the population that the energy crisis was a natural and insurmountable phenomenon in Georgia. We kind of got used to it. As if it should have been so. A few people were making tens of millions on energy scams, and we were sitting without electricity. You see the world illuminated and you are sitting in darkness. A new government came in and in 2-3 months the blackouts were over. It simply had the political will to solve the problems that had kept the country in darkness for years.

I cannot claim that the crime problem will be solved in 2-3 months, but addressing this issue also depends entirely on political will. However, what kind of political will we are talking about when a pro-Russian oligarch calls on us to treat the growth of crime with understanding, the mayor of the capital is the author of the quotation, ‘Eight thieves-in-law were sitting there’, and the thief of sneakers and the former chief prosecutor has risen to the level of an American-sanctioned FSB agent, who is protected by the entire state system... and I’m not even talking about the fact that crime is one of the driving forces behind Dream in every election.

What kind of political will are we talking about when the Ministry of Interior, State Security and the criminal world have formed a single conglomerate that feeds the government and keeps our country in darkness?