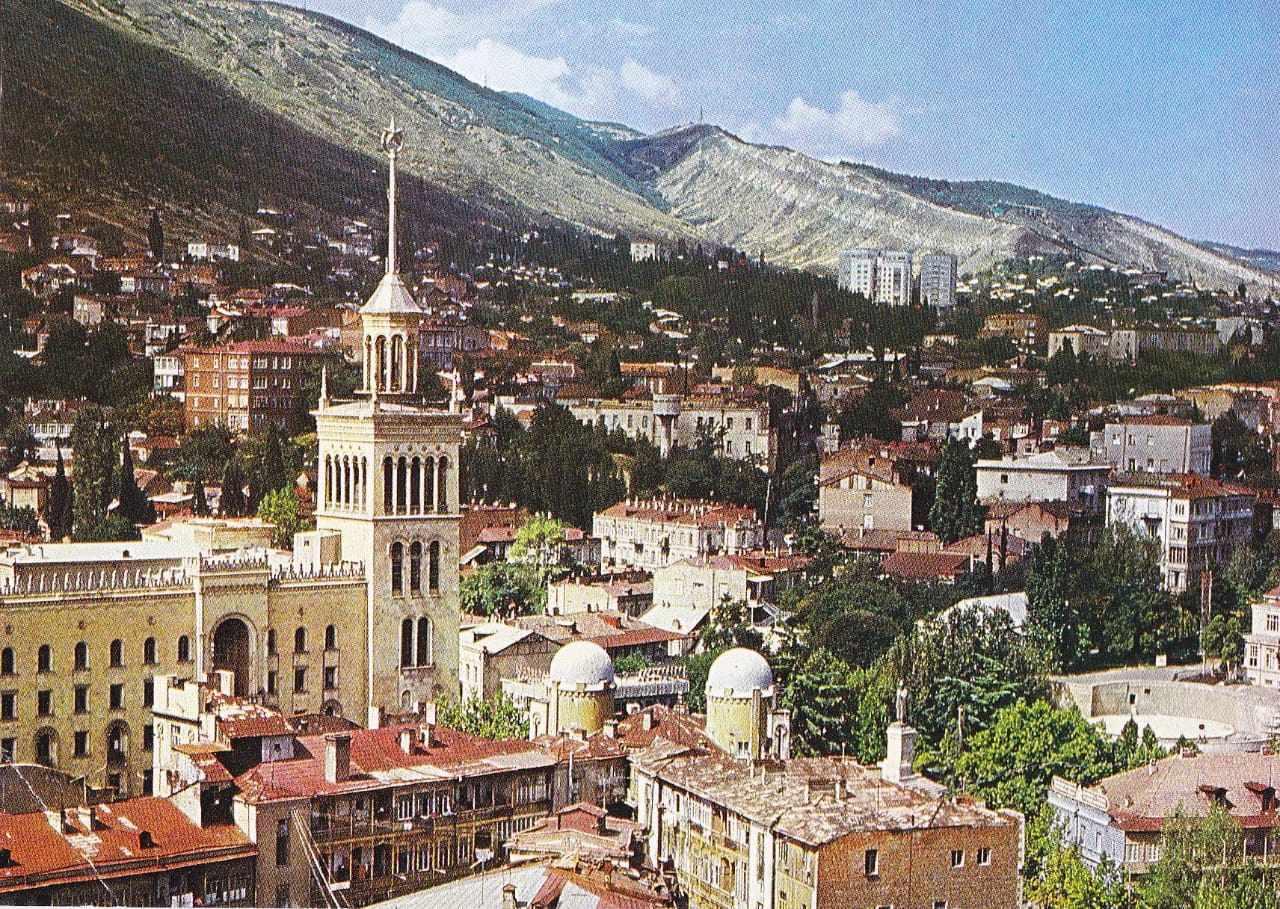

Author : Buba Kudava

Among the countless rulers who have had power in this world, whether they ruled a state or people, there have been very few women. In most countries there have been no such examples at all. They simply did not exist, nor could they have been imagined.

Most ruling women came to the arena as consorts or regents—the wife of a pharaoh, mother of an emperor, sister of a king, stepmother, mistress, co-ruler of the ruling man... A woman might have found herself at the helm of the country because of her own talent, ability, and charm, incomparable beauty or extraordinary attractiveness; sometimes because of the stupidity of a young male ruler; and other times—due to the weakness of the stronger sex’s nature—a woman might have temporarily taken the reins of power into her own hands. Not most, but almost all women have been such rulers, and of those very few cases there are even fewer exceptions where a woman became a legitimate, supreme, equal ruler to other male monarchs—by rule, order, status, title, recognition by the royal court, and the approval of subordinates. Most of these crowned ladies were self-proclaimed—having deposed their husbands, children, or parents, they seized the throne and then gained legitimacy.

But what happened in Georgia was something very unique and finding exact analogues in the past is not an easy task. King George III of the united Kingdom of Georgia, grandson of the great David Aghmashenebeli and one of the most important figures of the Middle East, had no son. What he intended could only have been found in faraway lands or in other centuries, both in the past and afterwards. And, as we have said, very, very rarely. And somewhat differently, like the pharaoh-ship of Hatshepsut or the reign of Cleopatra in ancient Egypt, the reign of Irene in eighth-century Byzantium, Wu Zetian in China, Catherine the Empress in Russia, or more recently, the monarchy of Elizabeth in England.

In short, today everyone knows it very well from early childhood, we know it from history and from Rustaveli that the king had no son and wanted his daughter to reign. We know the end, it is already very familiar and very famous today, but look at it through the eyes of a nobleman, a bishop, a warrior, a servant, or a peasant who lived in that era and in that region, and you will be bewildered. You may not belong to that era but imagine what would have happened to them when they heard about this incredible intention.

What? A woman rule? The story was unspeakable, unheard of, extremely disturbing and outrageous not only to our tradition but to the world around us. There had been many childless kings in the history of the world, including in our former kingdoms, but at such times the king would either crown a family member—a brother, cousin, or what-have-you—or choose an adopted son. Or, if he had a daughter and decided to do so, he would bring in a son-in-law—sometimes to reign, sometimes to father a future king, and sometimes he would marry his daughter to the heir of a neighbouring country, thus laying the foundation for the unification of the two states.

King Giorgi behaves differently. He does not seek a son-in-law to crown as king, nor does he seek a man of royal blood to pass on his crown. ‘The king had no other son, only a daughter,’ we learn from the story, as if the only solution was to make his daughter king, as if he were the only one with that destiny and everyone else had sons to continue the royal line. It seems that Giorgi III decided to make Tamara queen regnant when he was sure that he would not have another son.

Yet, there are two huge, seemingly insurmountable obstacles standing in the way: one obstacle, as I have said, is the revolutionary nature and unacceptability of the idea, and the other is called Demna Uplistusuli. As long as there is a young man in the royal family—such as the son of a previous king or the eponymous grandson of a previous king, as well as the representative of the senior male line and the only direct heir of the Bagrationi family—it is very difficult for Giorgi III to explain to the people and the monks, the Church and the nobility why there is a woman on the royal throne.

In short, to put it bluntly, as long as Demna is alive and well, Giorgi cannot enthrone his daughter, and if Demna has not committed an unworthy act, he could not be easily removed.

Giorgi intertwines the two problems and intends to solve them at once. He gets rid of Demna—first by meeting with Ivane Orbeli (the king’s hand must also be involved in this story), then by incitement, then by rebellion—by provoking a rebellion or pretending not to notice the preparation process, then by enraging the public, and finally by suppressing the rebellion. He gets rid of him so that no one could object to anything—what and why are you doing this and that. And no one can find fault in his actions; on the contrary, he saved the country from turmoil! This was also calculated: Demna is castrated rather than executed (‘he got mercy!’). Soon he dies (guess now—by himself or with the help of others?), but let him blame himself, they would say.

The victory over the camp of those who sewed treason and alarm, the punishment and destruction of the torturers and the silencing of the traitors will be followed by the great strengthening of Giorgi, and it is there that the long-awaited day will come when the revolutionary plan must be presented to the public, excited by his victory, enraged by the uprising of the rebels, or intimidated by the defeat of Demna-Orbeli.

Probably, they expected from Giorgi what we have mentioned above—a written or unwritten rule in the world community of God’s anointed ones—to choose a son-in-law, to enthrone him or to declare his son-grandson as his successor. And he immediately brought Tamar to the forefront, first as co-regent, and, in the near future, as sole ruler! Already victoriously, already openly, already with her head held high. He introduces her immediately, ‘the next day’, when the situation is still topical, and the story has not had time to cool down.

The source puts it this way: ‘No sooner had the historian finished his discourse on the suppression of the rebellion than he presented his daughter to the people and made Tamar his co-regent, his right hand.’ This is how it is written in the Chronicles, and this will be the crowning move of the triumphant king. When else would he have found such a precise time for it?

Finally, let’s also pose the following questions:

Why didn’t his uncle take steps to ensure his nephew became king once he became convinced he had no son, before the rebellion matured? After all, had Demna-Demetri been aware of his uncle’s decision upon reaching adulthood, he might not have entertained thoughts of rebellion. Perhaps there was nothing personal at play, but rather the political-clan unacceptability of his brother (David V) and his followers, who were murdered or accidentally killed, which was the primary reason for Demna’s rejection.

From time to time, you will hear this opinion: What would have happened if Demna and Tamar had married? It would have been beneficial for the country. However, at that time and in that kingdom, such marriages were not permitted due to the prevailing traditions and beliefs of the people. Such unions were considered to be too closely related, a taboo that still holds true today. Unlike Western or Eastern monarchies, where such ties were sometimes accepted, in our culture, they were perceived as sacrilege. However, one might ponder: Would a woman’s coronation appear more unconventional than the marriage of cousins?

And again, when King Giorgi rejected the project of making his son-in-law king, was he driven by paternal instinct or special feelings for his daughter? Did he trust his intuition or did he, as usual, calculate everything down to the last detail? Did he go all-in, or did he see something in Tamar’s abilities that convinced him of the rightness of his decision? Or did all his anger over the absence of a son turn into hope for Tamar, leading him to such a radical new solution?

What more can be said here? Let’s leave it for separate reflections.