Author : Zaza Bibilashvili

Cramped conditions are a Georgian disease. Nowhere is there such an insatiable, systematic, collective craving for cramped and artificially created discomfort as here in this country. Perhaps I’m exaggerating because of my bias towards Georgia, and this is the case everywhere—for example, in the dusty markets of East Asia or the colourful cities of Bengal where all castes and parallel realities converge, but.... we are ‘Georgians, so we are Europeans’! There is no such thing in Europe!

One is cramped everywhere in Georgia:

I graduated from school without ever being able to leave the school building after classes (because of the half-open double door) without enduring a long stampede.

I graduated from the university without ever witnessing the main entrance door of building No. 1 opened (except for the day when the Temple of Knowledge was visited by Shevardnadze, who had just arrived from Moscow to see the burnt and scorched Tbilisi). Instead, we were all ushered in through the lower ‘side’, the partially opened emergency entrance.

‘Stadium? Wherever I have been to a football game: in advanced—at the expense of the intelligent population—England, in famously straightforward Germany, in bohemian Spain, and even in the days of my Soviet childhood, in hateful Russia! That’s where you’ll find crazy fans—and just crazy people—that you won’t find here. But only in Georgia is entering the stadium associated with a lot of stress. If you don’t leave some of your dignity at the entrance, you won’t be able to get in. It’s a rule. Or rather, a tradition that has become a way of life, devoid of any meaning or understanding.

Well, the stadium is, after all, the realm of sports, and to complain about the slight physical strain associated with it is even kind of embarrassing... Take the theatre! Or the opera house. Okay, they open only one wing of the door when entering to check tickets, but what’s the problem about exiting? Why don’t they open both wings?! Have they come up with some secret idea that can’t be disclosed?

No matter how wide the street is, a Georgian street vendor is bound to lay out his merchandise so that a passerby can barely walk through. I understand—in a narrow space you move slower and there are more chances that the goods on the counter will attract attention, but if, God forbid, you want to buy something? Then you’ll have to block the road and stop those behind you...

That’s okay. What can we do? Maybe that’s the way it’s supposed to be. Or, as we said, it’s the rule. We’re used to living like this and don’t realize that maybe things could be arranged differently, much better and more conveniently.

However, let’s not focus on the street vendors... Have you seen ‘trendy’, ‘prestigious’—or ‘elite’—neighbourhoods with million-dollar villas or ‘exclusive’ settlements built for the chosen few in an ‘ecologically clean environment’ in which pedestrians and cars can move freely? Probably not. On the contrary, you will remember many of them, where the owners of residential palaces, surrounded by huge fences, left a passage for one car only. They don’t care about trespassers, you’ll say. But aren’t they bothered themselves?! Or don’t they have guests? Or haven’t they heard that a man can’t live by square meters alone?

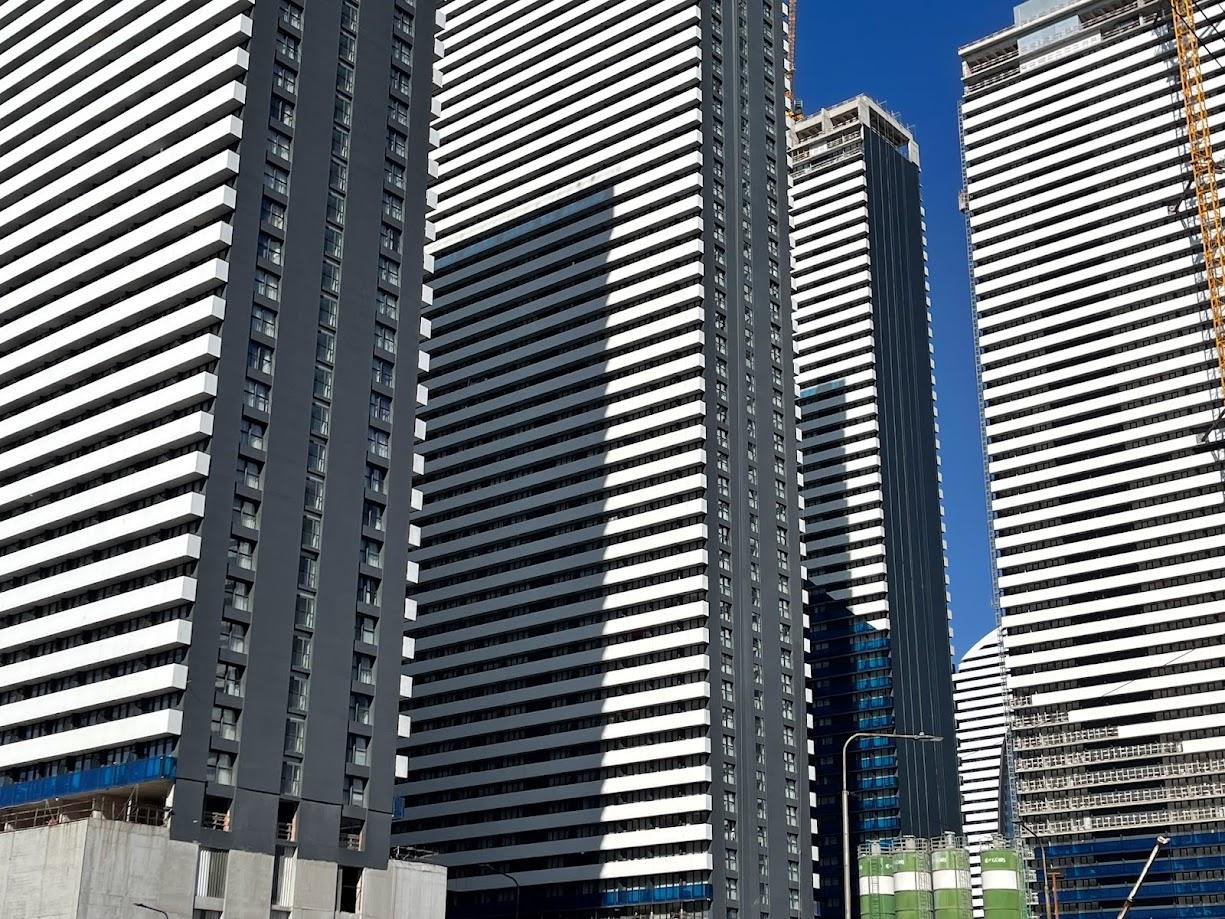

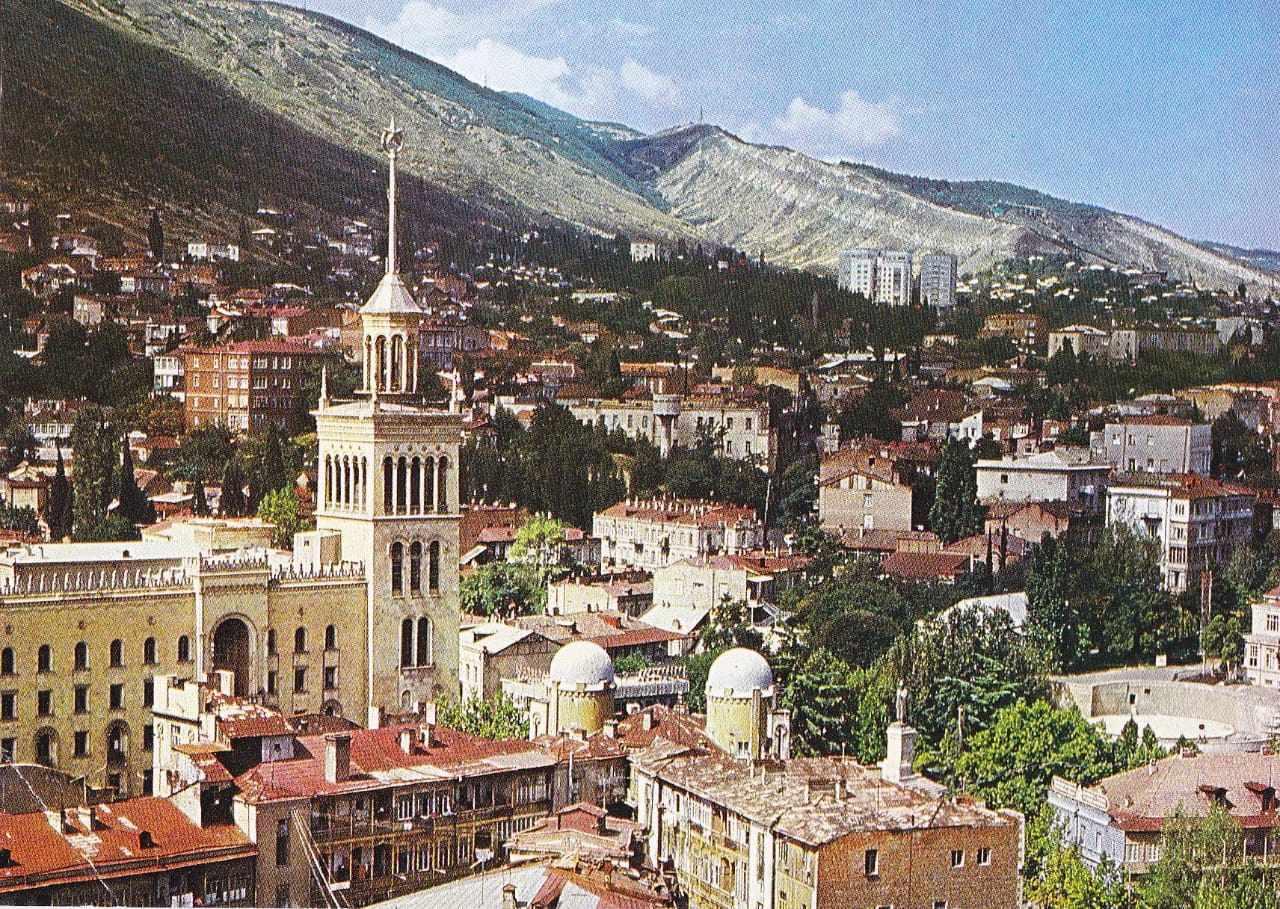

We should also mention apartment buildings (Tbilisi is a city of apartment buildings; meanwhile, Batumi and other urban centres are also becoming so): on the site of a dilapidated shed or in an open field—even if the house is designed from scratch—a Georgian developer will plan everything so that both the client and the passerby suffer from the same cramped conditions. The new $10 million sports palace on Saburtalo has been extended to the edge of the road like a dagger to Zviadauri’s1 throat... and the old sports palace is surrounded by buildings of eclectic style and taste so densely that one can barely squeeze around this architectural landmark of Tbilisi, even on foot, let alone in a car. In Zugdidi, the houses for IDPs were built on a vacant lot so close together that they look like branches growing from one trunk.

New Gldani was being born before our eyes in Gudauri and Bakuriani, and in Gldani itself and the former ‘Akademgorod’—New Giza, if you like, Gaza. Batumi, which 10 years ago was a coastal city, became a victim of thoughtless development and a sad monument of human greed. The most tragic thing is that these wounds do not heal, and the damage is irreversible.

Whether it is a building or a new shopping centre, it is located on the street in such a way that it not only blocks the sidewalk (and where there are still sidewalks left, they are replaced by grey buildings, commercial objects, or gas stations), but also the driveway. And inside, inside the building—if you get inside—you’ll be greeted by the splendour of the luxurious, nouveau Gruzin2 world and hugged around your waist... but, uh… will you get in? And at what cost? That is the question!

And parking? As if it is not difficult to plan indoor and outdoor parking lots so that the joy from the increase of the coefficient and conversion of square meters into dollars would be crowned with some good deed, and the additional suffering of drivers who survived on narrow avenues and in the hellish traffic jams of the capital would not be aggravated by the senseless waste of time. But no! Let the drivers suffer! After all, time has no value here.

Cramped conditions among us are the fate not only of a person, but also of a feast. The queen of Georgian sadness, Guliko Kereselidze from ‘Shanghai’, said for good reason that a table is valued for its crampedness. A plate with already cooled shashlik should be elegantly placed on a plate with salad Olivier and a plate with assorted pkhali, so that, while taking a piece of cream pastry from the third tier, you do not drop it into a greasy bowl of stew and accidentally wipe your sleeve dipped in chakhokhbili on the innocent person sitting next to you...

In Georgia, where there are so many vacant and undeveloped places both in spiritual and material space, crampedness, or tightness or narrowness has become our national brand. Tightness in old Georgian means scarcity, poverty, or limitation, and even a Georgian, who is not bound by a sense of public good, makes a choice for it every day. Sometimes consciously, and more often without thinking, as if instinctively striving to remain in self-imposed discomfort. Could it be that, as is the case with some whimsical people, we are driven not by a motivation to solve problems, but by a subconscious desire to keep lamenting?

Let it rip where it is narrow, Georgians said carelessly and turned this saying into a belief. ‘Let it rip where it is narrow,’ we say without thinking, and with our own hands we narrow, uglify, make our living space impassable and uninhabitable year after year, gnawing aggressive ugliness into the virgin landscape of Iberia, raising generations into aesthetic cripples, and mutilating our own psyche.

I don’t know whether it’s masochism turned into a national sport, civic myopia, lack of common sense, or the spiral of self-harm characteristic of a backward society? Maybe all of them together... Either way, the fact remains that this road has already narrowed like the blood vessels of a long-term drunkard before a heart attack.

If it rips, it will be too late.