Authors : Dodo Chumburidze, Bejan Khorava

Abkhazians: Ethnic and Demographic Aspects

‘Abkhazia is an inseparable part of Georgia, and Abkhazians share a strong cultural bond with Georgians’—these words and the ideas behind them do not belong to us alone; they can be found in the works of many authors and are often heard. In fact, linguistic, toponymic, anthropological, and other types of data clearly confirm the close connection between Abkhazians and Georgians.

Some Georgian scholars see modern Abkhazians as a people made up of two distinct ethnic groups: the first is the Abkhaz, i.e. an ancient Georgian race, and the second is the Apsu, who are of Adyghe-Circassian origin. The term ‘Apsu’ itself is the self-identification of this people, dating back to the 18th century.

Archival materials and various studies indicate that the historical populace of Abkhazia has primarily been Georgian. Until the 19th century, all material cultural monuments in Abkhazia were Georgian, apart from the Sukhumi castle constructed by the Turks. Since the 8th century, Abkhazia has been governed not only by rulers with Georgian affiliations but also by representatives of Georgian families, originating either from the Bagrationi dynastic circle of Tao-Klarjeti or from local lineages such as Marushiani, Shavliani, Dadiani, and Sharvashidze. The Hymn Book of Bichvinta attests that the population of Abkhazia was predominantly Georgian before 1621. Presently, a sizeable portion of Abkhazia’s population bears Georgian surnames, with only a small minority possessing North Caucasian surnames.

All this is evidence of what we started with: Abkhazians are part of the Georgian political and cultural world, and Abkhazia has always been an integral part of Georgia.

Abkhazians. From the collection of D. Ermakov.

The Essence of the Abkhazian Problem

What is the origin of the conflict between two brotherly peoples? The fact that the Russian-Georgian war took place in Abkhazia in 1992-1993 needs no proof. However, the roots of the conflict between Georgians and Abkhazians go back to the end of the 19th century. During this period, the Russian Empire sought to isolate the Abkhazians from the Georgian ethno-cultural world to pave the way for their assimilation and the annexation of this naturally rich region of Kolkhita (which it eventually achieved). Anti-Georgian sentiments were artificially instilled among the Abkhazians, and a merciless struggle was declared against the cultural-historical unity of Georgians and Abkhazians.

The transition of worship in Abkhazian churches from Georgian to Church Slavonic and the introduction of Abkhazian writing based on the Russian alphabet served this purpose.

The process of alienation of Abkhazians continued even during the years of Soviet rule. In 1921, after occupation and annexation of Georgia by Bolshevik Russia, isolationist policy became active again. For Abkhazians, Russian became the language of education, culture, and communication. They gradually broke away from the cultural and historical traditions that had inspired their previous generations.

In the 70-80s of the last century, Abkhazian separatism opposed the national liberation movement of Georgia, the main goal of which was the restoration of the state independence of Georgia.

Who Broke the Unique Georgian-Abkhazian Unity and When

After the total occupation of Georgia by the Russian Empire in the 19th century, separatist aspirations began to emerge among the multi-ethnic population of Georgia, including both Georgians and Abkhazians. Russian imperial chauvinist circles tried to strip the Abkhazians of their identity and foster discord between them and the Georgians.

As in the previous century, during the Soviet period, Russian scientists organized special expeditions to Abkhazia, wrote books that falsified Abkhazia’s past, downplayed the cultural and historical role of Georgians in the region, and laid the foundation for the colonization project aimed at complete denationalization and russification of the region. At the beginning of the 20th century, 35 Russian settlements were founded here. Churches, schools, and cultural institutions served only to instil Russian identity. Separatist propaganda destroyed the unique unity that had existed between the two peoples. Scientific expeditions organized by the Russian Academy of Sciences in Abkhazia had political rather than scientific goals.

It is significant that when Georgia managed to regain its independent statehood, it was able to normalize relations with the Abkhazian people. This was the case in the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) and the independent Georgian state restored in 1991.

The Abkhazian Issue in the First Democratic Republic of Georgia

During the First World War, the liberation movement of the Georgian people intensified. At the same time, to separate Abkhazia from Georgia, Russian authorities were discussing the question of joining Sukhumi district to the Black Sea Governorate and separating the Sukhumi diocese from the Georgian exarchate, which caused great concern in the advanced Abkhazian circles. Then, in April 1916, a deputation of Abkhazians arrived in Tbilisi and met with the tsar’s viceroy, Grand Tsarevich Nikolai Romanov, and the exarch of Georgia Metropolitan Platon (Rozhdestvensky). As a sign that the deputation expressed the will of the entire Abkhazian people, it included representatives of the Abkhazian nobility and peasantry.

On behalf of the Abkhazian people, the deputation made demands to the viceroy and the exarch: the Sukhumi district should not be annexed to the Black Sea governorate, the Sukhumi diocese should not be separated from the Georgian exarchate, and the Georgian language should be taught in Abkhazian parochial schools. The tsarist regime was forced to comply with the wishes of Abkhazian society.

On November 8, 1917, the Abkhaz People’s Council was established. On February 9, 1918, a delegation of the Abkhaz People’s Council arrived in Tbilisi and met with members of the Georgian National Council. They agreed that Abkhazia would have broad autonomy within independent Georgia.

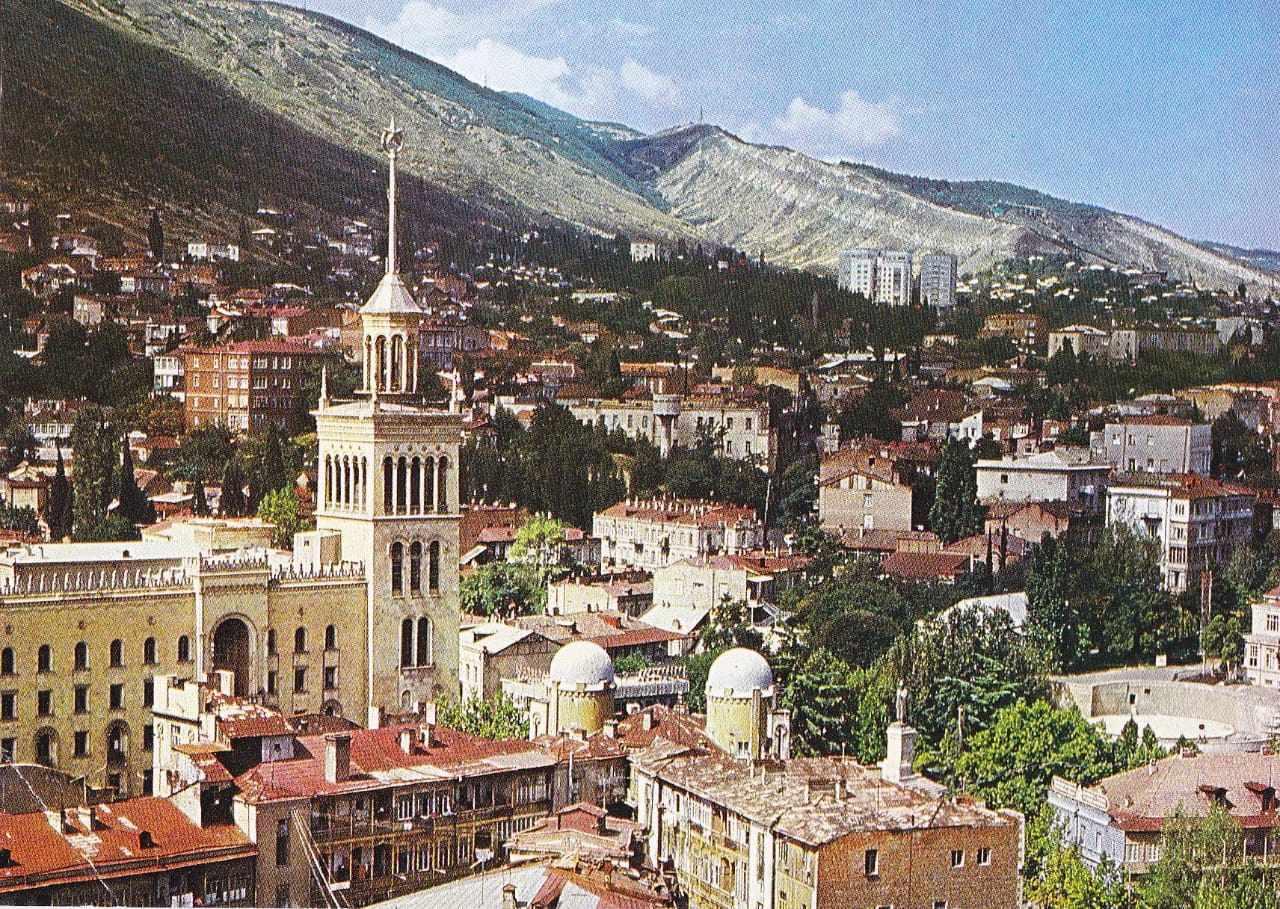

Members of Abkhazia’s deputation in Tbilisi, 1916.

Members of Abkhazia’s deputation in Tbilisi, 1916.

After the June 1918 proclamation of Georgia’s independence, and so in June 8, an agreement was signed in Tbilisi with a delegation of the Abkhaz People’s Council making the autonomy official. Meanwhile, in 1918-1919, Russian Bolsheviks and monarchists separately tried to conquer Abkhazia. The Georgian army, together with Abkhazian military units, repeatedly saved this territory from occupation. These military and political actions were determined by the demand and support of the local population.

Akaki Chkhenkeli, a member of the Georgian government and a renowned diplomat who grew up in Abkhazia, was deeply committed to addressing the issues faced by the Abkhazian people. Together with his childhood friend, Arzakan Emukhvari, an Abkhazian politician and member of the founding assembly of Georgia, as well as chair of the government of Abkhazia’s autonomy, Chkhenkeli dedicated much effort to building a state where both Abkhazians and Georgians would have equal opportunities for democratic development.

A clear example of the concern of the authorities of the Democratic Republic of Georgia for the plight of the Abkhaz population was the issue of the return of Abkhaz Muhajirs (exiled persons) to their homeland. In February 1920, Abkhaz Muhajirs Marshania and Margania congratulated Grigol Rtskhiladze, the head of the Georgian mission in the Ottoman Empire, on the de facto recognition of Georgia’s independence by the Entente countries. On behalf of the entire Abkhazian diaspora, they appealed for assistance in returning to their homeland. Grigol Rtskhiladze forwarded this request to the head of the Georgian delegation, Nikoloz (Karlo) Chkheidze, at the peace conference held in Paris after the First World War. The Georgian delegation in Paris took specific diplomatic steps to prepare the international legal grounds for the return of Abkhaz Muhajirs to their homeland.

On April 7, 1920, Karlo Chkheidze sent a letter to the Supreme Council of Entente countries, requesting their support for the Georgian government in facilitating the return of Abkhazians who had been exiled to the Ottoman Empire by Russian tsarism. However, the occupation of Georgia by Soviet Russia ultimately thwarted this initiative.

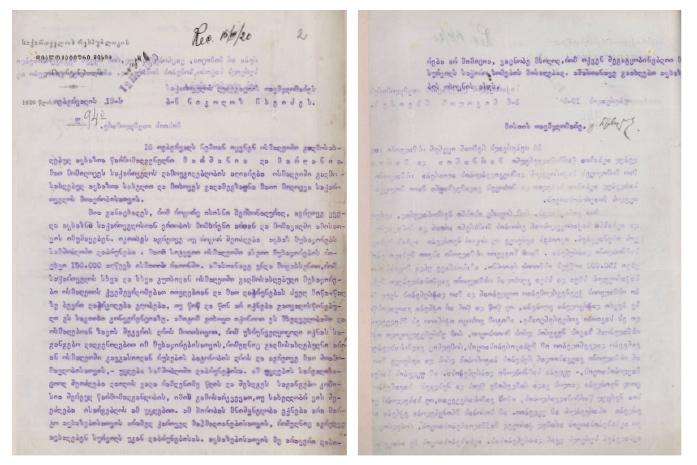

Grigol Rtskhiladze’s letter to Nikoloz Chkheidze

Grigol Rtskhiladze’s letter to Nikoloz Chkheidze

The Draft Constitution Adopted by the People’s Council of Abkhazia in 1920

In the first chapter of the draft constitution of the autonomy of Abkhazia, adopted by the People’s Council of Abkhazia in October 1920, it was stated: ‘Abkhazia is a part of the Democratic Republic of Georgia as an autonomous unit. Abkhazia shall remain independent as long as its independence is not limited by the current constitution.’ In Article 8 of the draft constitution, it was further outlined that the following aspects were common for Abkhazia and Georgia: a. Foreign policy; b. Monetary system; c. Customs; d. Post and telegraph; e. Army. However, the military formation was recruited by the Commissariat of Abkhazia according to the principle of territorial recruitment and consistently served Abkhazia, except for exceptional cases when the state was at war. In peacetime, the presence of other military units in Abkhazia, aside from the territorial army, was to be permitted only with the permission of the Abkhaz People’s Council. The extensive autonomous status of Abkhazia was enshrined in the constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, which was approved by the constituent assembly on February 21, 1921.

Arzakan Emukhvari

Arzakan Emukhvari

Perestroika and the Issue of Abkhazia

During Gorbachev’s rule, Abkhazian and Ossetian separatism took on a very specific purpose, as determined by the imperial centre: To contain the Georgian national liberation movement and its sovereignty. The leaders of the national movement, Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava, recognized the importance of preserving the unity of Georgia and the importance of Abkhazia in this context. Therefore, they also addressed the issue of Abkhazia, exposing the Kremlin’s treachery and proposing solutions to overcome the artificially intensified confrontation in Abkhazia.

The central political party of the Abkhazian ethnocracy and the institutional core of separatism was the People’s Forum Aidgylara, founded on December 13, 1988. ‘Aidgylara demanded the abolition of the four-tier structure of the Soviet Union’s national-state organization (union republic, autonomous republic, autonomous district, autonomous okrug) and the establishment of a federation based on the horizontal principle. In the case of Georgia, this meant upgrading the status of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia and the Autonomous District of South Ossetia to that of a union republic with direct subordination to Moscow.

Sukhumi, Hotel ‘Abkhazia’, 1968.

Sukhumi, Hotel ‘Abkhazia’, 1968.

At the initiative of Aidgylara on March 18th, 1989, in the village of Likhni of the Gudauta district, a gathering was held. The so-called appeal of Likhni to the governing bodies of the Soviet Union on the secession of Abkhazia from Georgia and its incorporation into the Soviet Union with the status of a union republic was adopted. This fact further aggravated the ethno-political crisis in Abkhazia, which escalated into an armed conflict in July 1989.

The Assembly of the Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus and Societies Established on an Ethnopolitical Basis in Abkhazia

After the July 1989 conflict, the separatists intensified the situation in the autonomous republic. They placed certain hopes on nationalist and extremist groups of the North Caucasians who initiated a significant ideological attack against Georgians. On August 25-26, 1989, the first congress of the ‘Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus’ took place in Sukhumi, during which the decision to establish the Assembly of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus was made. The goal of the new movement was declared at the congress: To create a republic for the mountain peoples of the Caucasus with Sukhumi as its capital.

სოხუმი. 1989 წელი

სოხუმი. 1989 წელი

Associations forming to unite non-Georgian-non-Abkhazian communities residing in Abkhazia played a significant role in shaping the separatist political landscape. On January 27th, 1990, based on ethnopolitical motives and Russian-imperial interests, the Armenian ‘Cultural-Charitable’ society, Krunk, was established. Initially, an organization with the same name was illegally founded in December 1987 in Karabakh. Similarly, the Slavic House, or the Society of Russian Culture in Abkhazia, was established on April 23, 1991, serving a similar role. Slavic House was a purely ideological political organization, the function of which was to carry out Russia’s imperial policy in Abkhazia. It performed this function through direct links with the Soviet security services, consolidating all non-Abkhazian groups operating in Abkhazia on an anti-Georgian platform.

The Policy of Zviad Gamsakhurdia’s Government in Abkhazia

On March 9, 1990, under the positive pressure of the Georgian National Movement, the Supreme Council of the Georgian SSR, during the rule of the Communist Party, passed a resolution that considered the invasion of Soviet troops in February 1921 as an intervention and occupation. In addition, all legal acts that had been adopted since February 1921, including the treaty of December 30, 1922, which established the Soviet Union, were declared null and void.

In order to stop the ongoing processes of disintegration within the Soviet Union, on April 3, 1990, the ‘Law on the Rules of Secession of the Union Republics from the USSR’ was published under the signature of the President of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev. According to the law, the decision on secession of a union republic from the USSR was to be made by referendum, and in a union republic that included autonomous republics and autonomous oblasts, the referendum was to be held ‘separately in each autonomy’. For Georgia, which had two autonomies, leaving the Soviet Union would have been a challenge because the Kremlin could have manipulated the autonomies to its advantage.

In this situation, multi-party parliamentary elections were held in Georgia on October 28, 1990. The elections were won by the Round Table—Free Georgia bloc led by Zviad Gamsakhurdia.

During Gamsakhurdia’s rule, the Georgian government’s policy in Abkhazia was based on the principle of territorial integrity of the country. Given the situation in Abkhazia and its neighbourhood, especially given the Kremlin’s support for Abkhazian separatism and the real prospect of fomenting an ethnic crisis, this policy was characterized by a tendency to use tactics of forced compromise with the Abkhazian ethnocracy.

Tactics of compromise based on ensuring special political rights of Abkhazians within the Georgian state was not an end in itself of the political game of the Gamsakhurdia government: The issues of territorial integrity of Georgia, territorial-administrative unitarism, and inviolability of the space of sovereignty were not subject to compromise.

Referendum of March 17, 1991 in Abkhazia

On December 4, 1990, Vladislav Ardzinba became Chair of the Supreme Council of the Abkhazian SSR. In the context of a strong national-state position and mass support for the Gamsakhurdia government, Ardzinba and his entourage, despite their anti-Georgian orientation, were forced to accept the existing rules of the game and refrain from active separatist political actions, with the exception of the Kremlin-mandated referendum of March 17, 1991, on the preservation of the USSR Union on the territory of Abkhazia.

On February 28, 1991, the Supreme Council of Abkhazia decided to participate in the referendum to preserve the Union of the USSR. In this regard, on March 12, 1991, an address from the Chair of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, to the Abkhazian people was publicized. In his address, Gamsakhurdia emphasized the common Kolkhetian origin of the Georgian and Abkhaz peoples, genetic kinship, cultural, and historical ties, and the treacherous goals of the empire. He called on the population of Abkhazia to boycott the referendum on the preservation of the Union of the USSR and to support the referendum on the restoration of Georgia’s independence. ‘Independent Georgia will offer you much more,’ Gamsakhurdia stated, ‘than the modernized Soviet empire, which aims to assimilate and russify all small peoples. A truly independent Abkhazia will coexist autonomously within Georgia, with genuine self-government, just as it did for centuries during the existence of the United Kingdom of Abkhazians and Georgians.’

Vladislav Arzinba responded to Gamsakhurdia’s appeal. In the reply letter dated March 14, 1991, he agreed with the part of it where the centuries-old relations of the Abkhazian and Georgian peoples, the close connection of their independent cultures, and the closeness of national traditions were discussed. However, he pointed out that if Abkhazia remained a part of the USSR, then the participation of Abkhazian citizens in the decision of the future of the Soviet Union was their full right.

On March 17, 1991, a referendum was held in Abkhazia. Although the separatists managed to gain the necessary number of votes for a simple majority, 50.3%, by excluding the Gali district, where more than 50 thousand voters resided, the reaction of the national government of Georgia was legitimate and prompt. On March 22, the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia recognized the results of the referendum as illegal and null and void.

Referendum on the Independence of Georgia

Just a few days after the Soviet referendum, on March 31, Georgia held a referendum on independence. Despite the boycott announced by Ardzinba and Aidgylara and other separatist organizations, which caused the referendum to fail in the Gudauta district and Tkvarcheli, 61.27% of the total number of voters took part in the referendum. Of these, 97.73%, or 60% of the total number of voters, voted in favour of Georgian independence.

On April 9, 1991, based on the results of the March 31 referendum, the Supreme Council of Georgia adopted the Act on Restoration of Independence. On April 14, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia introduced the position of the President of the Republic and made appropriate amendments and additions to the existing Constitution. On the same day, the Supreme Council elected Zviad Gamsakhurdia as President of the Republic.

Georgia’s quest for independence worried the Kremlin. In early April 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev and Zviad Gamsakhurdia had a telephone conversation. Gorbachev warned Gamsakhurdia that Abkhazia and South Ossetia would be lost to him if Georgia declared independence and withdrew from the USSR. This was not a warning, but a threat that was later realized by Russia.

Compromise Tactics of the Georgian Government in Abkhazia

The referendum on the independence of Georgia, the declaration of independence, and presidential elections dealt a serious blow to the separatist movement in Abkhazia. At the same time, with Russia’s military presence in Georgia and the imperial centre having real leverage to foment ethnic conflict in Abkhazia, Gamsakhurdia continued his compromise tactics. In his inaugural speech on June 7, 1991, he touched upon the issue of the creation of an independent state of Georgia and the future political status of Abkhazia in this state. He reaffirmed once again the unwavering will of independent Georgia to protect the inviolability of the national rights of the Abkhaz based on constitutional guarantees of political autonomy:

‘The establishment of the state should be based on such political principles of governance and self-government that exclude the conflict between the state and its constituent parts, protect the unity of the state, and contribute to the protection of the interests of the structural units of the Republic. One of the necessary foundations of the national-state arrangement should be the recognition of the political rights of the Abkhazians as an indigenous nation of Georgia and traditional Georgian-Abkhazian friendship. Abkhazia is an integral part of Georgia. It is the homeland of both Georgians and Abkhazians. The political autonomy of Abkhazia and the inviolability of Abkhazian national rights are constitutionally guaranteed by the Republic of Georgia. Along with the real restoration of Georgia’s independence, traditional relations between Abkhazians and Georgians should be restored,’ stated the President.

Thus, Gamsakhurdia focused on the broad political autonomy of Abkhazia within Georgia. In his opinion, the Abkhazian question could be resolved only within the framework of a constitutional state. A serious step in this direction was the new electoral law of the Abkhazian Supreme Council agreeing with the Georgian authorities and the elections to the Supreme Council held on the basis of this law.

The Idea of Caucasian Unity and its Political Context

It is indicative that throughout 1991, Ardzinba did not pass any separatist legal acts. At the same time, starting from 1991, Gamsakhurdia put forward the idea of ‘The Caucasian House and Unity of Caucasians’, which even became the state ideology of the government of that time. He perceived the idea of Caucasian unity as a necessary ideological basis for Georgia’s leading role in the Caucasus.

The idea was based on the theory of unity of ‘Iberian-Caucasian languages’ of Georgian linguist Arnold Chikobava, according to which Georgian, Abkhaz–Adyghean, Vainakh (Chechen-Ingush), and Dagestanian languages originated from the same root and therefore these peoples are also related. Gamsakhurdia was interested in this concept primarily as a political doctrine, and he began promoting it in 1988-1989. By advancing the idea of the ‘Caucasian House’, he aimed to isolate Abkhazian separatism gradually, presenting it to the Caucasian mountaineers as not only anti-Georgian but also an anti-Caucasian movement orchestrated by the Kremlin.

.jpg) Port of Sukhumi

Port of Sukhumi

Compromise Version of the New Election Code of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia

In June-July 1991, intensive consultations took place between Tbilisi and Ardzinba’s entourage. A bundle of compromise constitutional accords was developed, consisting of a new electoral code and a set of constitutional amendments. The legislation came into effect in July-August 1991.

On July 9, the session of the Supreme Soviet of Abkhazia adopted a new electoral code, the law ‘On the Election of Members of the Supreme Council of the Abkhaz SSR’. The law provided for the division of single-mandate constituencies into ethnic zones and the staffing of the autonomous parliament according to the principle of ethnic quotas, while observing the basic principles of an equal number of voters. The Abkhazian ethnic zone was represented by 28 single-mandate constituencies, representing 17.3% of the total population; Georgian constituencies numbered 26, representing 47.7% of the total population, and other nationalities had 11 constituencies. Therefore, out of the 65 members of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia, 28 parliamentary mandates were allocated to Abkhazians, 26 to Georgians, and 11 to representatives of other nationalities.

On August 27, a package of constitutional amendments was adopted. According to the Law ‘On Amendments to the Constitution of the Abkhazian SSR’, Article 98 of the Constitution was formulated as follows: ‘Laws and other acts on the issues of the legal status of the Abkhazian SSR shall be adopted by two-thirds of the total number of members of the Supreme Council of the Abkhazian SSR’. On the same day, the law ‘On the Abkhazia SSR Universal-People’s Voting (Referendum)’ (new edition) was adopted, in the fifth article of which it was stated that the consent of two-thirds of the total number of members was required to appoint a referendum on constitutional changes.

Was the model of ethnic quotas unprecedented?

The opinion that the ethnic quotas model was unprecedented is erroneous. Of 40 members of the Abkhaz People’s Council elected on February 13th, 1919, 17 were ethnic Abkhazians, 15 were Georgians and 8 were representatives of other nationalities. The Supreme Council of Abkhazia of 1986-1991 convocation had the following ethnic composition: out of 140 members—57 Abkhazians, 54 Georgians, and 29 representatives of other nationalities. So, the principle of representative preference of ethnic Abkhazians with purely quantitative indicators existed practically at all stages of the history of autonomous parliamentarianism. The fact that ethnic quotas were de facto rather than legally authorized does not change anything in this case, of course.

In international practice, the principle of political-ethnic or political-confessional quotas underlies the constitutional order of some states as a means of post-conflict settlement or conflict prevention. There are many examples of the realization of the principle of ethno-political quotas, including the political system of Cyprus before the 1974 crisis and the administrative structure of some Swiss cantons.

The main goal of the 1991 compromise was to neutralize the Russian orientation of the Abkhazian ethnocracy and begin its reintegration into the Georgian space. The 28+26+11 formula introduced the concept of indigenous (28+26) and non-indigenous (11) ethnic groups in Abkhazia. The Abkhazian ethnocracy recognized Georgians as indigenous ethnic groups of Abkhazia with appropriate state and legal guarantees, and vice versa. The constitution of Abkhazia was amended: Instead of ‘Georgian SSR’ it was written ‘Republic of Georgia’, by which the Abkhaz side recognized the fact of liquidation of Soviet symbols in Georgia, and the Abkhazian SSR was mentioned as part of the independent Republic of Georgia.

‘The Law on the Political and Legal Status of Abkhazia’ entered into force only after its adoption by the central and autonomous parliaments of Georgia. This effectively ruled out the legal possibility of a unilateral decision on the status. The main point was that the Abkhazian ethnocracy recognized the territorial integrity of Georgia. Without any facilitation missions or mediation, it entered into a political agreement to remain within a unified state, without demanding federalization or confederation of Georgia. In doing so, the Abkhaz ethnocracy recognized the independent Georgian national government as the source and subject of both its own political rights and the entire political process in Abkhazia. Directly or indirectly, the Abkhaz recognized that the basis of their autonomy status was not due to the self-determination of the Abkhaz nation or any allied-imperial act, but the political will of the Georgian government and its agreement with it.

Ritsi Lake

Ritsi Lake

Was the Electoral Compromise Package Sufficient for the Adoption of Abkhazia’s Constitutional Amendments?

The compromise constitutional package encompassed the entire spectrum of Georgian interests in Abkhazia. A decision on Abkhazia’s legal status required a qualified majority, which could not be achieved by Abkhaz MPs alone, nor by members of other nationalities allied with them. Thus, the slim majority of ethnic Abkhazians in the Abkhaz parliament, along with any coalition that did not include a Georgian delegation, could not make up a constitutional majority, since the consent of the Georgian faction was required to pass constitutional amendments. From a political standpoint, this meant that the Georgian president had the ability to override any illegal decision to secede Abkhazia from Georgia or prevent the implementation of such an act. The mechanism for blocking the breakdown of Georgia’s territorial integrity and the president’s de facto and de jure veto over the possible secession of Abkhazia are the main features of the 1991 compromise. As part of the compromise package, a qualified majority was required not only for resolving constitutional issues but also in the event of government formation.

The nomenclature preference of the Georgian side was guaranteed by the Georgian ethnicity of the First Vice-Speaker of the Parliament and the Chair of the Council of Ministers. All of this compelled the parties to actively cooperate with each other, meaning constructive collaboration between the two main ethnic (Georgian-Abkhaz) segments of the population was necessary for any significant decision-making. Thus, the compromise constitutional package aimed to reduce tension in Abkhazia, avoid military conflict, and confine the purported confrontation within the parliamentary-constitutional framework. Such a tendency was noted in the fall of 1991, when Gamsakhurdia declared null and void some anti-constitutional acts of the Supreme Council and the Government of Abkhazia concerning the creation of the Customs Service of Abkhazia, etc.

Thus, within a short period, complex political processes in Abkhazia were managed, separatism was restrained through peaceful means, and legal, political, and international mechanisms were established to prevent Kremlin provocations. These included a compromise election law, changes in the constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, and the concept of the Caucasian House. However, the work initiated could not be completed. The process of establishing a political balance system based on a compromise constitutional package was interrupted by the 1991-1992 coup d’état.

.jpg) გაგრა

გაგრა

Elections of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia on September 29, 1991

t is indicative that the elections of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia were held on September 29th, 1991, on the basis of the new electoral code. In the prevailing situation, when every vote in the Supreme Council of Abkhazia would have been decisive, in the conditions of the boycott declared by the opposition, the Georgian side was unable to elect even 26 MPs, while the Abkhazians elected all 28.

In addition, although 6 of the 11 candidates of other nationalities were elected with the support of the Georgian side, four MPs elected by the Georgian side (V. Vasiliev, M. Jaloviani, A. Gomtskiani, A. Zebeliani) defected to the Abkhazian side at the first session in January 1992. According to the agreement with the Abkhazian side, the chairman of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia was supposed to be an Abkhazian and his first deputy a Georgian; also, the chairman of the Council of Ministers was supposed to be a Georgian and his first deputy an Abkhazian. In addition, to avoid misunderstandings, the candidacies of the Chair of the Supreme Council and the Chair of the Council of Ministers were to be submitted in one package. Vladislav Ardzinba was unanimously elected as the Chair of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia, with Tamaz Nadareishvili as his first deputy. However, the Georgian side could not agree on the candidacy for the Chair of the Council of Ministers. Eventually, Ardzinba broke the agreement and persuaded the majority of the Supreme Council to appoint the Chair of the Council of Ministers. Additionally, it is noteworthy that Ardzinba avoided open confrontation with the Georgian side by appointing not an Abkhazian but his loyal, yet still Georgian, Vazha Zarandia as the Chair of the Council of Ministers. This indicated that not all was lost.

Bzipi Valley

Bzipi Valley

What the Coup d’État in Tbilisi Changed

The December 1991–January 1992 coup d’état overthrew the Gamsakhurdia government. The coup d’état was followed by the dissolution of the Supreme Council of Georgia and the suspension of the Constitution. The coup d’état created a qualitatively new situation in the political space of Abkhazia. The compromise model of 1991 collapsed, and the balanced party-political system built upon it collapsed as well. The political clan of Ardzinba set itself the goal of separating Abkhazia from Georgia and ensuring the provision of military and legal grounds for this. On December 29, 1991, the Supreme Council of Abkhazia adopted a resolution on the transfer of military units and state institutions stationed on the territory of Abkhazia to the authority of the Chair of the Supreme Council. According to the decree, a so-called provisional military council was established under the Chair of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia, which by its structure and purpose was a coordinating body of the future military system of the separatist regime.

The coup undermined the main political axis blocking the secession of Abkhazia—the institution of the President of Georgia, who had the constitutional prerogative of veto in this matter; as well as the constitutional and legal mechanism for preventing the secession of Abkhazia. On January 2, 1992, the Military Council of Georgia suspended the Constitution of the State, and on February 21, 1992, it formally restored the 1921 Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. The resulting legal situation gave Ardzinba the opportunity to activate actions against the state under this pretext.

The following two meetings of Boris Yeltsin with the Georgian and Abkhazian leaders show how Russia’s new imperial policy worked in such a situation: On June 24, 1992, a working meeting of the Head of State of Georgia and the President of the Russian Federation was held in Dagomis, where Eduard Shevardnadze received from Boris Yeltsin the ‘sanction’ to conduct an emergency operation on the territory of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, apparently with a guarantee of neutrality from the Russian Federation. Meanwhile, on July 18, 1992, an unofficial confidential meeting of Yeltsin with Ardzinba and other Abkhaz separatists took place in Sochi. At this confidential meeting, the separatists received the sanction to start the war with the guarantee of Russian military intervention. Russia supported both sides and controlled the development of events.

On July 23, 1992, the Abkhazian faction of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia, in violation of procedural norms and rules, adopted a resolution on the abolition of the 1978 Constitution of the Georgian SSR and the restoration of the 1925 Constitution of Abkhazia, which, in effect, constituted a declaration of the secession of Abkhazia from Georgia.

The War in Abkhazia and the Failure of Peace Initiatives

On August 14, 1992, hostilities began in Abkhazia. The junta and Abkhazian separatists tried to provoke war in every possible way, contributing to its outbreak. They were blind executors of the plan developed in Moscow.

On August 21st, the exiled president sent an appeal to Ardzinba and proposed to reinstate the status of an autonomous republic and the 1978 constitution in order to restore peace in Abkhazia. The exiled president took practical steps to stop the war in Abkhazia. On his initiative and with Chechen mediation, peace talks were organized between representatives of the legitimate authorities and Abkhaz separatists.

On May 4, 1993, Gamsakhurdia addressed the Abkhazian people and declared: ‘The bloody military coup in Georgia and the establishment of an illegal criminal regime are the main reasons for this fratricidal war... Justice demands the recognition of certain mistakes made by the leadership of Abkhazia, in particular by the Supreme Council, which changed the current constitution without the consent of the qualified majority and thus contributed to the situation. Future generations will not forgive us if, following the example of our wise ancestors, we do not sit down at the negotiating table to peacefully and politically resolve all disputed issues. Only the restoration of the legitimate government in Georgia will immediately end the conflict and create a basis for peace talks. I believe that we should agree on the issues of state structure’.

The peace initiatives of the exiled president remained unrealized. On July 27, 1993, a peace treaty was signed in Sochi, which in fact foreshadowed the loss of Abkhazia. On September 16, the Abkhazians broke the agreement and resumed hostilities. In this situation, Gamsakhurdia refused to travel to England at the invitation of Margaret Thatcher, for which he was seriously preparing, and returned to Georgia on September 24. He tried to unite the pro-Shevardnadze armed forces and subordinate units of the National Guard to fight against the enemy, but the government thwarted this plan.

On September 27, 1993, Sukhumi fell; in the following days, the Abkhaz separatists occupied the territories of Gulripshi, Ochamchira, and Gali districts without a fight, and on September 30, 1993, they hoisted the separatist flag on the Enguri Bridge, on the administrative border of Abkhazia. Shortly after the end of the war in Abkhazia, on December 31, 1993, Gamsakhurdia died under unknown circumstances.

Bedia Cathedral

Bedia Cathedral

What Georgian-Abkhazian Relations Should Be in the Future

Akaki Bakradze wrote: ‘A Georgian should know that he cannot expel Abkhazians from Abkhazia; an Abkhazian should also know that he cannot expel Georgians from Abkhazia; Georgians and Abkhazians have lived together in Abkhazia since the day this part of the land appeared and began to exist. This will be the case in the future. Since God has destined us to live together, no matter how much we hate each other, we must find ways and methods of living together and we must use our minds in this search.’

We, both Abkhazians and Georgians, should remember the words of the founder of Abkhazian literature, Dmitri Gulia (1874-1960): ‘We have built our culture under one sky, on one land, together we will protect our national identity and our land. It is not enough to say that we are fraternal nations. We are people of the same psyche, the same customs, the same rules, the same psychology. I do not think that Georgians have a closer brother than Abkhazians, Abkhazians also consider Georgians the same, and we have been protected by this brotherhood, whoever destroys this brotherhood, in the words of Rustaveli, “is his own enemy”.’

Indeed, the historical experience of Georgian-Abkhazian relations allows us to see the future of these relations: When Georgia will be not only sovereign, but also a politically, socio-economically, and legally strong country, Abkhazians will also realize that their development and preservation of their ethno-cultural identity is possible only through coexistence with Georgians. Then there will be no more Abkhazian-Georgian problem as it used to be in the past.