Author : Giorgi Antadze

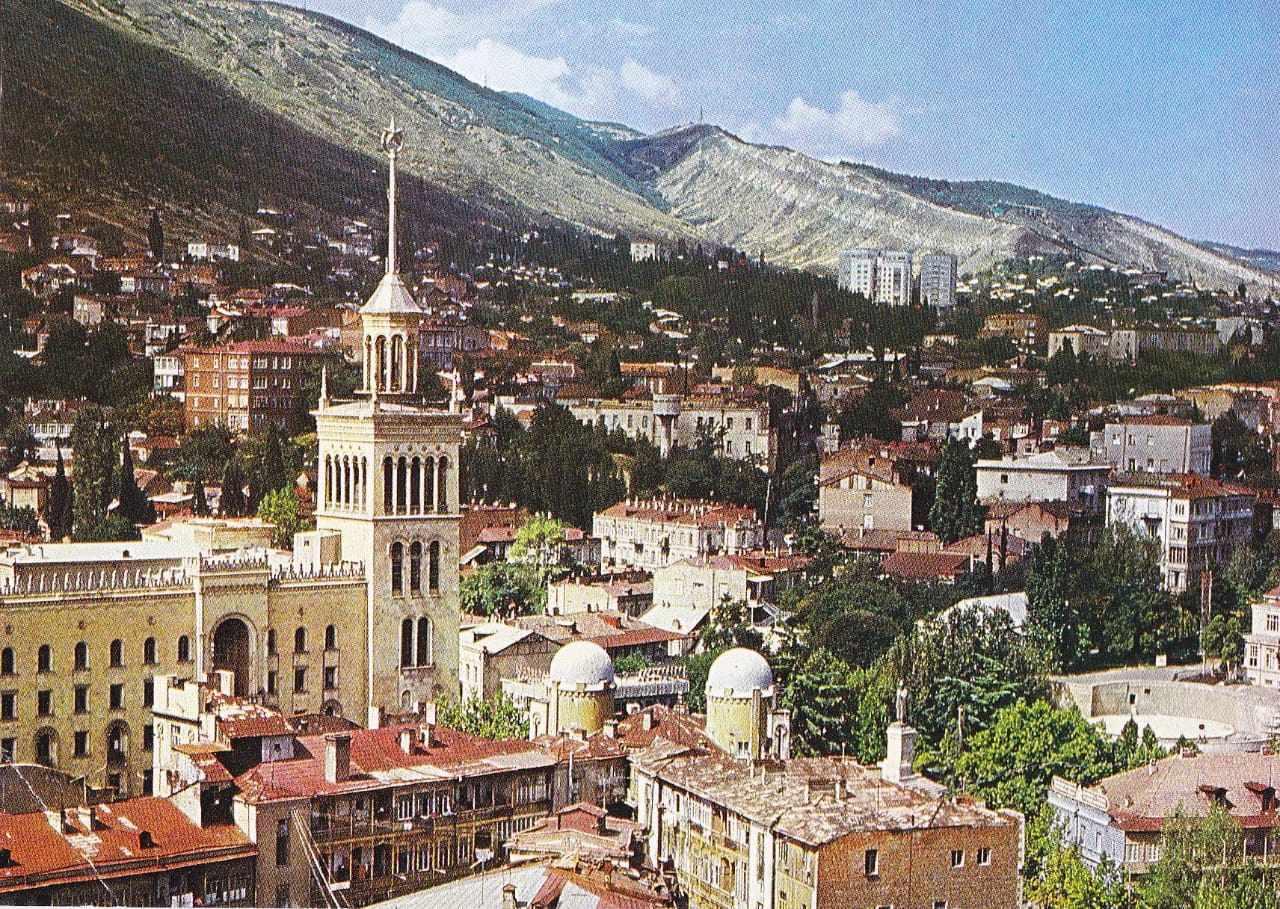

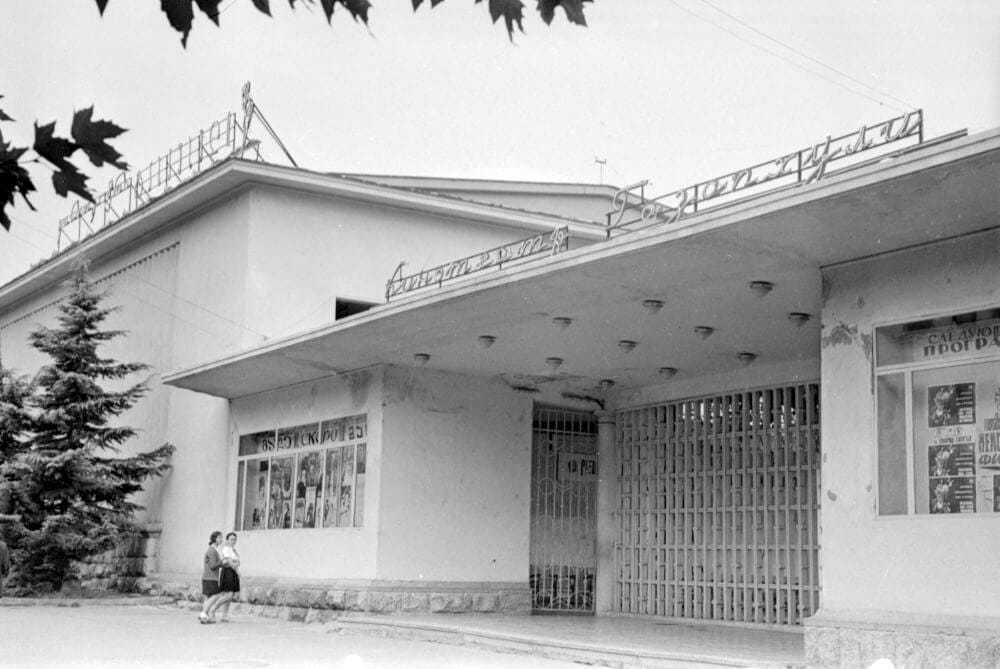

In the Soviet Union, we were familiar with Western cinematography only to the extent that the strict hand of censorship allowed us. To this day, I don’t know how Gazapkhuli Cinema located on Anagi Street managed to do this, but it is a fact that it was the only place in Tbilisi where films, whether banned or not approved by Soviet censorship, were constantly shown. In other theatres, masterpieces of European and American cinema were shown only based on political expediency. The main principle behind the greenlighting of Western films was to highlight the negative aspects of capitalism and demonstrate class struggle. In this vein, real movie masterpieces would sometimes appear, albeit cut by the censors, altering their essence and sometimes even their titles.

There was yet another ‘sacred’ place where one could watch Western movies, bypassing censorship. However, the ‘House of Cinema’, or DomKino in the slang of the time, was not accessible to everyone, and only a select few could attend movie screenings. However, it was not just a place to watch movies. It could safely be called a fashion show of clothes brought by dancers on tour, a spraying of perfume fragrances bought from black marketeers, or simply a place where talking about Federico Fellini in Russian was considered a good tone. Modern technology and globalization have put an end to these privileges, otherwise only members of a special caste could enjoy these benefits of Western civilization.

It was technology that dealt the first blow to the privileges of the Soviet elite. The VCR invaded the Soviet cities of the 1980s like Godzilla invaded Tokyo. The videomagnitofon, that is, the Soviet VCR, was the real detonator of the Iron Curtain. Despite the ‘dedicated’ work of Soviet customs officers, forbidden movie productions recorded on videotapes kept appearing. A new business developed: video rentals. They brought about a wonderful form of entertainment: locking oneself in one’s apartment for a few days and watching foreign movies with friends for hours on end.

Dubbing banned movies into Russian was an underground business. To make it difficult for the Soviet secret services to recognize the voice of the interpreter, the latter often pinned a clothespin to his nose and thus recorded his voice. In addition to pornography, westerns, kung fu, and thrillers, real movie masterpieces became available. For some reason, we pronounced the titles of the movies only in Russian: ‘Adnazda v Amerike’ (‘Once Upon a Time in America’), ‘Paslednoe tango v Parizhe’ (‘Last Tango in Paris’), ‘Kharoshi, Plakhoi, Zloi’ (‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’), and so on.

The result of this social explosion was that even ordinary people talked freely about Fellini, we began to distinguish between pornography and erotica, we also learned a little about the history of the rest of the world and one day we discovered that the comedy-drama La Dolce Vita (sweet life) was not as sweet as the dreamers trapped in the ‘cage of the peoples’ had assumed.

The Iron Curtain was slowly opening. Music, movies, sports, and Pepsi-Cola appeared in the first glimpses. The victory of Dinamo Tbilisi in a European tournament, in addition to the vicissitudes of Western soccer, taught us that cheering in the stadium is not just a matter of swearing, but sometimes singing too. We learned in no time and created our own original innovation: we lit Soviet newspapers as torches in the stadium. The newspapers Pravda, Kommunisti, and Zarya Vostoka burned and turned to ashes in the hands of the victorious Georgian fans, and no one realized the symbolism of this scene.

Everything was ahead of us, including our Dolce Vita.

La Dolce Vita is the slogan of Italy. Fellini, Mastroianni, Sophia Loren, Zeffireli, Pavarotti, Celentano, the Great Toto and another Toto who years later joked from the stage in Tbilisi: Georgians, do you know what ‘katso’ means in Italian (he was not aware of the meaning of his surname in Georgian).

Italian soccer, Italian pop music, Italian opera, Italian fashion, Italian cinema, Italian sunglasses... They weren’t pink, but even in those dark glasses you could discern the colours of that earthly paradise. It turns out that there exists not only love at first sight, but also love with no sight at all: we all loved Italy, which we had not seen with our own eyes.

It was a different story though that had sparked my love for Italy. A few months after the military putsch, an Italian ‘investor’ and ‘patron of the arts’, accompanied by his Calabrian and Sicilian entourage, suddenly arrived in Georgia, which was devastated by Mkhedrioni and flooded with crime. He rented the top floor of the Hotel Adjara for housing and there… formed a queue, but what a queue it was! Anyone with a business idea in Georgia spent hours in the reception room of this Italian ‘investor’. Business projects ranged from bee poison extraction to a garbage recycling plant.

The projects approved by the Italian Angel Investor were considered on the sidelines of the military junta government. Some projects were financed from the state budget, some were financed by banks with a state guarantee, and some projects were shelved due to insufficient resources. For example, the garbage processing plant project could not be realized because it turned out that there was not enough garbage in the country (even with garbage, Georgians were unlucky).

In the end, the story ended like this: This Italian ‘investor’ embezzled the money he received from the budget or from the banks and disappeared one day, so that no one could find any trace of him. The only project that was really financed by Italians and worked was a Georgian-Italian pharmaceutical enterprise. I’m not sure how an honest pharmacist from Milan, Andrea Legori, who invested a significant amount of money in this project by Georgian standards at the time, ended up in the company of those swindlers, but the fact remains that it was this honest man who laid the groundwork for the modern Georgian pharmaceutical industry. This aristocratic pharmacist, who lived in the centre of Milan, in the former apartments of Giacomo Puccini, an admirer of opera and painting, an educated man with very refined manners, became for me a source of inspiration and a symbol of the true Italian, even though the one who brought him to Georgia was from a completely different ‘opera’.

During the period of cooperation with the Italians, I never managed to visit Italy. It was only five years later that fate smiled upon me, and I, unafraid of road difficulties, travelled from Tbilisi to Italy by bus. I boarded the bus rented for the participants of the Georgian Dance and Song Ensemble of the Medical Institute as a veteran dancer (although I had no idea about dancing, let alone singing). The ensemble was heading to a summer festival, and we had to travel all over Italy from south to north.

Not on Red Square in Moscow, not in St. Isaac’s Cathedral in Leningrad, not in Echmiadzin in Armenia, but I can say with full confidence that I received the first cultural shock of my life in Rome. (‘Rome is such that even a person who has seen much will never cease to be amazed and to admire it’ —Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, Journey to Europe). Later, while reading Sulkhan-Saba’s works, I imagined how this great Georgian had to hide his surprise, his ‘culture shock’, because of the diplomatic etiquette. I imagined how a person who came from then Georgia to Italy and France at the beginning of the XVIII century would feel, even though he was very educated, but still came from another world. I imagined and even experienced the same in the city to which all roads lead.

Another story related to ‘culture shock’ comes to mind. A few years after that story, representatives of the former Soviet republics were hosted in the United States under an American government program. After a month of internship, when saying goodbye to my American hosts, I made a pathetic Georgian toast about how I had fallen in love with America, with what impressions I was leaving this country and how I would miss everyone I met here.

When I started to get carried away, the American program director interrupted me and said: ‘Calm down George, don’t worry, you’re having a typical culture shock right now, try to calm down, and when you get back home it will pass in a few weeks, don’t be afraid.’ But I know for a fact that I didn’t have any ‘shock’ at that time, I was just making a toast in a very Georgian way.

Here in Italy, I was not expecting any shock at all—I was sure that I was ready to meet the ‘boot’ of the Apennines in every way. Every traveller goes through this stage: When you think you know everything about the country you’re going to, but with each passing day that ‘knowledge’ and stereotype is shattered and from those shards a whole new country is born that you would never have known from the stories of others.

We have been loaded with stereotypes about Italy and Italians. Today, Italy is one of the main tourist destinations for Georgians. Unfortunately, many Georgian immigrant women workday and night in Italian cities to fulfil the Georgian dream of doing nothing and ‘eating for free’ for their Georgian husbands. As we Georgians already know Italy well, I will not describe the sights of Italy, just offer you some sketches from the ocean of impressions.

Verona: There is also a village with this name on Gombori Road. But there is one difference: The central square of the Italian Verona is adorned by the main attraction of the city, the Arena di Verona. Every summer the Verona Opera Festival is held here. The Arena is a Roman amphitheatre, better preserved than the Colosseum. The acoustics of the Arena are further proof that no civilization greater than the Roman Empire has yet been created on this planet.

In Verona, tourists are first taken to the house of Juliet. Both the house and the balcony are fake, created by a certain American with an eye for marketing. He chose an old house in the centre of the city, brought a sarcophagus from the cemetery, sawed it and attached it to the wall of the house so that it looked like a balcony, on the entrance wall he attached a board with letters to be sent to Juliet, and since then, the line of tourists has not stopped. The real attraction of this house is the room where the costumes from the time of Franco Zeffireli’s masterpiece are exhibited.

Bologna: Italians call this city La Dotta, La Grassa, La Rossa—smart, fat, red.

Smart, because it is home to the Alma Mater Studiorum, the oldest university in the world, which has never stopped functioning since its foundation in 1088 and still educates thousands of students. Fat, because Bologna is the capital of the Emilia Romana region. This region is a gastronomic paradise on earth. Red, because most of the buildings in this city are made of red bricks.

Bologna is characterized by another attraction: Much earlier than Tbilisi, still in the era of the Renaissance, a campaign to build loggias was launched here. Due to the large influx of students, renting apartments in Bologna has always been a lucrative business, but demand has always exceeded supply. Therefore, the Bolognese began to massively increase the living space by building loggias. Unlike Tbilisi, Bologna’s loggias do not violate the architectural integrity and rest on beautiful arched supports instead of concrete girders. The arches are so interconnected that even when it rains in Bologna, you can walk around the entire city without getting wet.

Naples was also well known in the Soviet Union for the brilliant movie ‘Operation St. Januarius’. Even half a century after the filming of this comedy, Naples has not changed, it is still under the patronage of St. Januarius and the famous treasure is still placed there. Thanks to football today, this city has gained a special meaning for Georgians. If you get into a taxi at Naples airport and mention Khvicha Kvaratskhelia, you are guaranteed a 40-minute rapturous monologue by an Italian taxi driver on the way to the city centre.

At the time of my first visit, Neapolitans had not heard much about Georgia and Georgians. At that time, we were ‘perceived’ as Russian tourists and we were a huge source of income for our hosts, because the flexible and skilful Italians had already created the entire infrastructure for selling Italian shoes and leather goods. It was then that I first encountered the peculiarities of ‘capitalist’ marketing: You go into a store to buy a toothbrush and come out with a leather jacket.

In Naples we had our first taste of pizza, or as we called it: Italian khachapuri. Indeed, it is one of the attractions of Naples, but the crown jewel of Italian cuisine is not necessarily pizza. Pizza as we know it is believed to have been created in the 19th century, although there are ancient Roman frescoes depicting a similar dish. Pizza was considered the food of the poor because it was usually made with leftovers from other dishes. The popularity of pizza in Europe and especially in America was facilitated by a large wave of Italian emigration in the early 20th century. Is pizza related to khachapuri? Of course not. There are more differences than similarities between these two dishes. Only when khachapuri occupies the same place in world gastronomy as pizza does today will Georgians be able to say that khachapuri is something like pizza.

One of the greatest discoveries of the Soviet tourist during his first visit to Italy was ice cream. Italian ice cream, or gelato, was much better than Moscow ice cream, even that Eskimo ice cream sold in ГУМ and ЦУМ (famous department stores in Moscow)!

Pasta is the identity of Italians, as khinkali is the identity of Georgians. In the Soviet Union, for some reason, pasta was called ‘macaroni’, and all forms of pasta were called macaroni. Actually, Macaroni is only one kind of pasta. Italians have more than four hundred kinds of pasta.

The main question I was looking for an answer to during my first visit to Italy was the following: Are Georgians similar to Italians?

There are many similar dishes in Georgian and Italian cuisine. For example, mozzarella is very similar to sulguni, pizza is similar to khachapuri, ravioli is similar to khinkali, polenta is similar to ghomi. Italian grappa is our chacha. But this similarity says only one thing: We were once part of the Mediterranean culture and civilization. Then, cut off from this part of the world, we drifted for centuries in Asian mud and Russian swamp until we discovered again that our place and our Dolce Vita is in Europe, which is geographically not much farther away than St. Petersburg or Moscow.

As the bus headed toward the centre of European civilization under the cover of night, I thought it would be no problem to cover the distance. A quarter of a century has passed since then, and the road between us and civilized Europe is still travelled only by buses and airplanes.

And when we will overcome this distance mentally—no one knows.