Author : Levan Gurielidze

Bela Akhmadulina

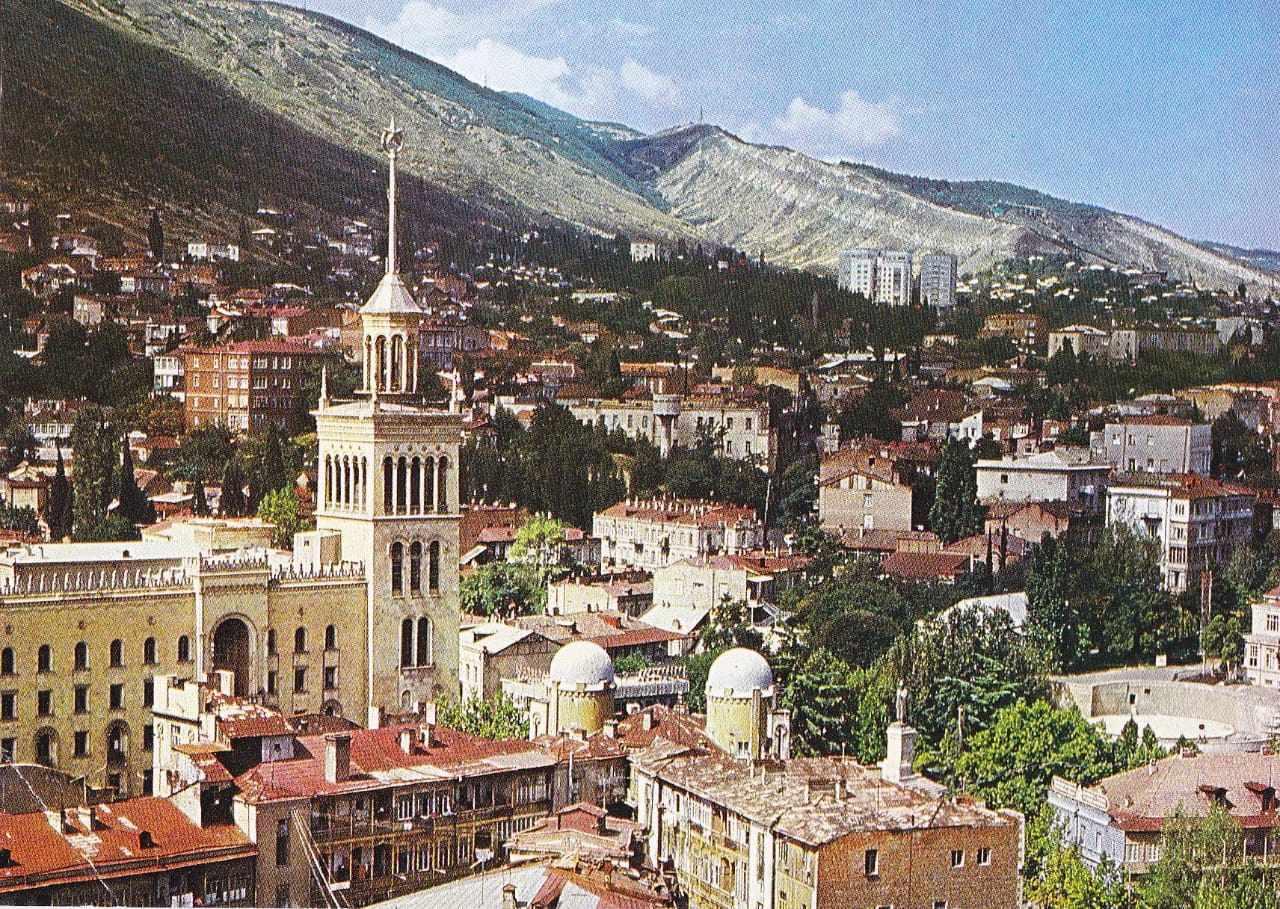

It was the late 70s or early 80s. I was sent from the institute on placement to a small, cozy town in Abkhazia. It’s summer, and a classmate is visiting me—the kind of classmate who isn’t just a friend but is like a brother, with whom I had shared a desk since the first grade. This classmate of mine loves to drink, and during the day, he asks me to take him somewhere where he can have something to drink that doesn’t look too much like a cafeteria.

I take him to the Litfond Bar. It’s called a bar, although it’s actually a buffet, and instead of a bartender, it’s served by the invariable hero of the satirical newspaper Krokodil—a waiter in a white gown. This bar has one advantage: it’s located on the seashore.

My classmate is drinking cognac, and his eyes are already shining before he takes a sip. We sit at a table—he pours small shots and looks at the sun, smiling at his angels, like a child in a dream. By the second shot, I suddenly notice a woman’s outstretched hand at my side—she reaches for my classmate sitting across from me and says in Russian, ‘Give me a light, please.’ My classmate knows what to do: He pours her a shot of brandy and smiles broadly.

I turned to the woman, and in my hands, I had a living Bela Akhmadulina! How could I not take advantage of the company of the poet who seemed to have fallen from the sky and, as they say, captured my heart, engaging in conversation with her? From that conversation, little remains with me to this day, but I remember distinctly how she mentioned Simon Chikovani (‘Simon? Well, yes—Simon—in Russian or in Georgian?’) in her own melodious way, and how affectionately and melodiously she pronounced the names of Paolo and Titian.

Meanwhile, my classmate poured cognac again, and Bela reached for it again. Of course, she drank another shot, after which Bela completely switched to Galaktion—she hadn’t forgotten her own translation, and recited ‘Mary’ with half-closed eyes:

Венчалась Мери в ночь дождей,

И в ночь дождей я проклял Мери.

Не мог я отворить дверей,

Восставших между мной и ей,

И я поцеловал те двери’...

‘Meri was crowned on a rainy night,

And on the night of the rains, I cursed Meri.

I could not open the doors

Rebels between me and her

And I kissed those doors’….

The only thing memorable on my part was that I wanted to introduce a little dissonance and asked her if she knew that Terenty Granelli had called Galaktion a ‘demon’. Bela was suddenly confused and asked me who Terenty Granelli was—apparently the Georgian friends of her circle did not waste time with Bela to reveal Terenty Granelli’s identity.

Meanwhile, my classmate poured again, and when Bela held out her hand again, he poured again, but this time my classmate suddenly exploded—it seems that he was tired of looking at the sun and he was upset by my behaviour—of course, by the woman’s clothes, her appearance, and age (Bela was wearing a simple sundress and her Mongoloid appearance with sunken cheeks matched the sundress perfectly) he realized that I wasn’t trying to seduce her and couldn’t understand who the woman was, that I preferred talking to her to toasting with a friend:

—What are you doing, man? How can you condescend to this cheapskate? She’s emptied the whole bottle... You traded me for her, my brother?

I jumped to my feet and rushed towards my classmate, trying to intercept the swear word coming from him, but the word had already been spoken, and unfortunately for me, it sounded like a swear word in Russian—but how could I intercept it!

When I landed in my seat, Bela was gone—I don’t know if her companions called her or if she had gone to the sea to swim. All the days I was out of sorts, I worried about whether Bela had heard the hurtful word or not. After a few days, when my visiting classmate left for Tbilisi, I visited the Litfond Bar again one evening.

I searched in vain for Bela with my eyes, but instead, my eyes came across the Tbilisi beau monde in the bar, who favoured Litfond in Gagra in the summer. During their conversation, I heard a phrase about how Bela Akhmadulina had wet her pants a few days ago. But it was said so tenderly and delicately—as if it were a praise of Ludovic by Sulkhan-Saba1—that everyone would want to wet themselves as poetically as Bela Akhmadulina!

They didn’t care—but I had a new worry—I had forgotten all about having insulted Bela, I was worried about whether our cognac was to be to be blamed for the incident with the poetess.

The Discreet Charm of the French Pronunciation

The Gagra Litfond Resort was a kind of mecca for the elite vacationers who came from the high circles in the Soviet period of Brezhnev. But regardless of the name, instead of engineers of human souls, it was more often their family members and relatives who came there, and besides them, employees of the Soviet party apparatus—that’s a given!

The number of women was particularly visible in the summer, and among them were some who, due to their age, did not participate in the romantic-intimate adventures of the summer sea, but instead met in the Litfond Bar after supper to sip coffee.

Along with the coffee, there were heated conversations about high matters—the problems of cinema and theatre, art, and literature in general, as well as news that was available only to them —the ladies of high society. Although they may not have been directly involved in the creative literary processes, they still fed on the byproducts of their fathers’ or husbands’ creative endeavours, as well as on the various high society gatherings from which thousands of rumours and false news emerged.

Let us not forget that they had access to news and events that were completely hidden from ordinary Soviet people and at the same time represented that privileged world for whom the doors of the foreign currency store ‘Beryozka’ were open for buying clothes and jewellery of foreign origin. Their children were also educated in special prestigious schools and travelled freely in Western countries, while for the rest of the citizens, Bulgaria represented the pinnacle of all foreign countries!

And so, one day it happened so that I became an unwilling participant in such a gathering because I was sitting near their table. They were discussing an article published in the Izvestia newspaper, authored by the newspaper’s columnist Melor Sturua. Our elderly compatriots remember that there was such a Russian-speaking journalist of Georgian origin who cooperated with Izvestia and supplied it with materials from the USA and Great Britain.

Today’s women’s talk was devoted to a discussion of Melor Sturua’s latest article, which depicted a polemic with politicians in the Western world. The discussion was led by a moderately overweight elderly lady who appeared to be trying to distinguish herself from the others not only by her role as a talk host but also by her provocative clothing: Her red-and-yellow top was tucked into green shorts, and on her head, she wore a headband with multi-coloured feathers. From today’s point of view, she looked like an oligarch’s parrot. Apparently, she had brought the newspaper and, impressed by the article, she often and savoringly mentioned the name and surname of the author, which in her pronunciation sounded like this: ‘Mellooor Sturuaaah’, with a sharp emphasis on the last vowel, revealing the author’s desire to sound French.

It is true that Russians try not to Frenchify their journalists, but to Russify all non-Russians, and for them both Dostoevsky and Tolstoy are indigenous Russians, but Sturua could not claim the heights of Dostoevsky, and seeing herself in the status of a French journalist as a defender of the interests of the Russian Soviet state flattered the lady’s ambition very much. Besides, it was not some revolutionary like Marat. ‘Mellooor Sturuaah’ sounded like ‘Charles Leroy’! Her companions readily agreed with her and praised the journalist between themselves—how skilfully Sturua interrupted the Western politician, what strong arguments he used to defend the superiority of the Soviet system and what diplomatic digressions he was able to use for this purpose.

The others, of course, also imitated the pronunciation of the main lady, repeating ‘meloor’ and ‘sturuaah’ in the French manner—one could hear the smacking of lips and clicking of tongues! And when she gave another example of the journalistic courage of the ‘French author’, unfortunately for her, the lady suddenly turned to me and, eager for approval, asked me to confirm some of her assertions—‘Isn’t that right?’

—Of course, it is the way you wish, I agreed, but with one small note: in Georgian surnames the emphasis should be placed not on the last vowel, but on the first vowel: that is, not on ‘Sturuaah’. but ‘Stuurua’.

I will not be able to describe the expression on this lady’s face, and I will have to turn to Ilia Chavchavadze’s Letters of a Traveler, when Ilia tells the Russian officer that he is working as a salesman for an Armenian merchant: Do you remember from Letters of a Traveler what expression the officer had when he heard this? This lady of mine had exactly the same expression, the only thing she didn’t say was: ‘At any rate, the Georgians are better than these,’ but she directly retorted: ‘How can you prove that he is a Georgian?

—What proof do you need, I replied calmly. What you think is the name of the author, is not a name, it is an abbreviation, and it means: ‘Marx-Engels-Lenin-October Revolution’—his father was a party worker and that’s why he called his son ‘Melor’!

No, they really liked and were proud of the achievements of their Soviet motherland, but mentioning the October Revolution was still not a good idea in those circles.

—October Revolution? The lady’s face flashed and turned red, and she immediately shouted to the other ladies:

—Why are we wasting time drinking coffee and chatting; won’t we have time for that in Moscow? We are wasting golden minutes. Well, get up and let’s go to the beach!

They all jumped up at once and followed her.

At the table, I was left with the newspaper Izvestia, on which one of the ladies in a hurry spilled the coffee which smeared brown the picture of the author of the article.