Author : Tamar Taralashvili

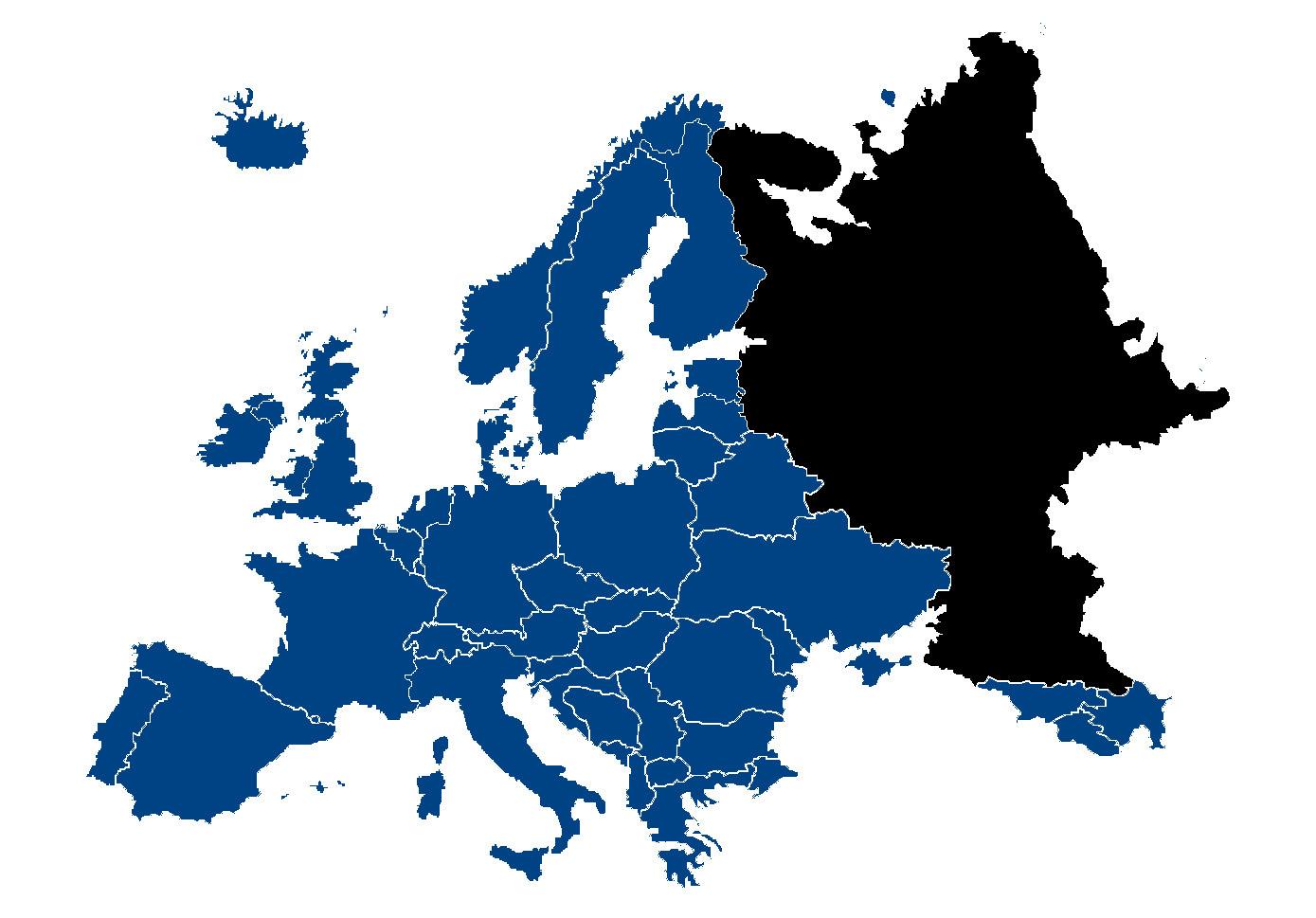

The rallies of March 2023 clearly demonstrated how important it is to involve young people in the country’s political processes. At the rallies against the ‘Russian Law’, young people expressed unprecedented unity and solidarity. The goal was one: Forward, towards Europe, and by no means towards Russia!

The cohesion, integrity, and capacity for self-mobilisation of young people came as a surprise to the country’s ruling authorities. The protest was also joined by Georgian citizens belonging to ethnic minorities from regions where political and civic activity and interest are typically low. It became clear that the Georgian Dream had overlooked the generation that grew up in freedom. Not just them, but also Putin. It became clear that the generation that grew up in a free Georgia would actively oppose pro-Russian policies and Russia’s growing influence in the country.

What happens if young people do not want to cooperate with you? The practice of Russian politics is to punish or to favour. Both cases are a great threat to the democratic present and future of the country. However, this did not become a hindrance factor for the ruling party and the Georgian Dream that is fused with the state. The State Security Service and other agencies began targeted arrests, political purges of the education system, and widespread disinformation through the pro-government media aimed at demonising young patriots.

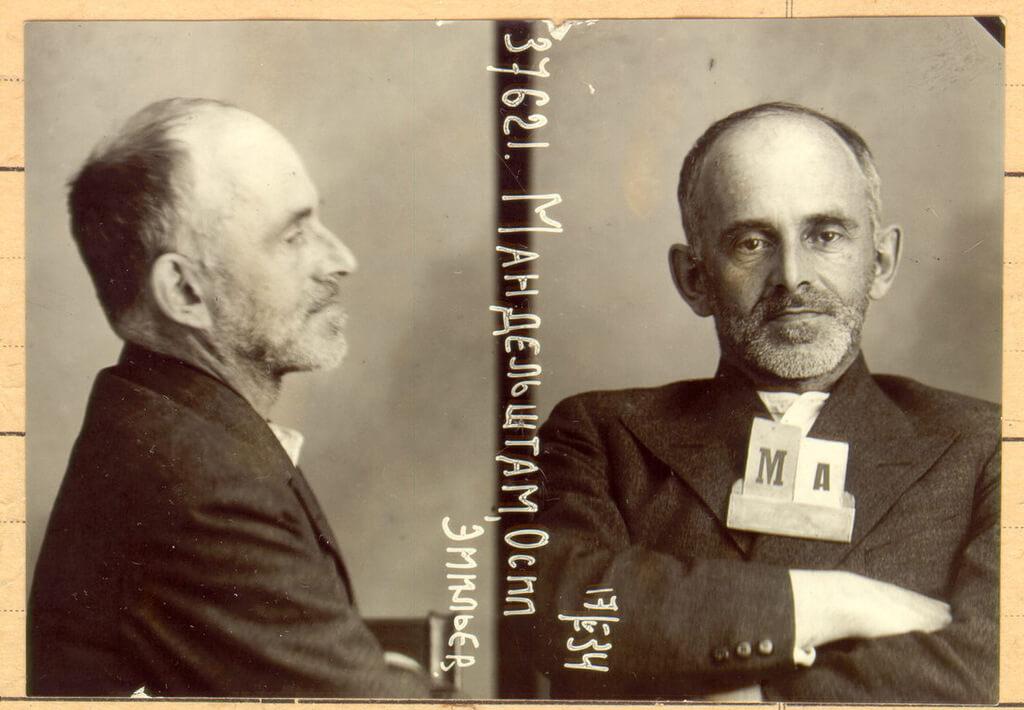

Here it would be interesting to recall how Russian youth was ‘tamed’ by Putin, who paid great attention to the political control of young people from the very first years of his presidency. The beginning of the 21st century was a time of profound changes for the young republics born in the post-Soviet space. It was a period of colour revolutions, the main driving force of which was determined by youth movements. In 2000, Serbia witnessed a wave of protests led by the Otpor movement, which led to the resignation of the incumbent president, Slobodan Milošević. In 2003, the Kmara movement in Georgia overthrew the Shevardnadze regime in the Rose Revolution. In 2004, the Pora movement led the Orange Revolution protests in Ukraine. In 2005, the KelKel youth movement took an active part in the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan. Less effective, but still important, were the continuing demonstrations in Azerbaijan involving the Yeni Fikir movement.

It was this chain of protests that made the West pay close attention to the events taking place in Russia and the formation of the Nashi (Ours) movement. By 2005, the Nashi movement already had over 120,000 active members, whose ages ranged from 17 to 25 years old. Suspicions quickly arose that the movement’s leader, Vasily Yakemenko, and the Nashi as a whole were under the patronage of Vladislav Surkov, a high-ranking official close to Putin. ‘A youth, democratic, anti-fascist, anti-oligarchic, anti-capitalist movement,’ reads the organisation’s description. It is registered as a ‘Government-organized Non-Governmental Organisation’ (GONGO).

By creating Nashi, Putin reduced the risk of a youth organisation gaining a foothold in Russia and threatening his regime with the colour revolution that many dreamt of. He publicly presented himself as a supporter of the youth. He actively met with them and took part in discussions to promote the ‘development’ of young people. The Western press soon gave the movement a name: Putin’s generation. During one of these meetings, Masha Drokova, a young commissar, demonstratively kissed Putin. Not many people can boast of having kissed Putin, that’s why this young woman went down in Russian history in a special way: Mashenka—the Girl Who Kissed Putin.

The movement was led by five thousand commissars, of course, on instructions from ‘above’. Correctly completed tasks were a prerequisite for the promotion and success of young people. Membership in the movement became a kind of business card for admission to universities or employment, even in private companies. After the difficult 90s, it was through this movement that young people were offered real opportunities, fun, and success. There was also an organised camp on Lake Seliger every summer, where young people received training, did military physical exercises, and met with high-ranking Duma officials to discuss their future plans.

The movement with the conspicuously red flag soon revealed links to the Leninist youth movement Komsomol, the only difference being that the red flags and T-shirts featured Putin’s face instead of Lenin’s. The symbolic load is easy to see: Putin’s desire to emphasise his ties to the Soviet Union and his fundamental role in the ‘New Russia’.

Putin’s strategy to attract young people in favour of his regime has been successful. In an interview with the BBC, Yakemenko proudly noted that ‘in recent years Putin has met with them more often than with all other youth movements taken together’.

Mass public speeches by Nashi were held precisely at the time and place where opposition movements were planning events. The demonstrations with racist, anti-liberal, and xenophobic content were well-funded, well-organised, and massive. They physically attacked anyone who publicly expressed an opinion against Putin, including journalist Oleg Kashin, who was physically attacked by skinheads.

The movement uses aggressive hate speech and acts against the United States and Western countries, not shying away from attacking diplomats. In 2005, protests were organised against the British ambassador to Russia, Tony Brenton, simply for attending a conference called ‘The Other Russia’ organised by the opposition. Cynical as it may have been, the movement later announced that its active members would be allowed to study in Britain because ‘after all’ British universities and education were among the best in the world.

Summer camps, luxury apartments, and hotels in the centre of Moscow, and free meals for protesters at McDonald’s, cost the Kremlin more than 200 million roubles (about $6.7 million at the time) in 2010 alone, according to Yakemenko. In 2019, the movement officially split into several independent groups, meaning that the ‘Putin generation’ continues to actively support the Kremlin’s interests in numerous ways.

Let’s turn back to Georgia. After the March 2023 protests, Georgian government leaders began actively ‘vilifying’ young people (GenZ). In addition to the punitive measures that began during the protests, they actively used so-called national and traditional narratives against them. Soon the youth organisation ‘Students for Justice’ started an active protest against the Ilyauni State University. Ilyauni, with its liberal values, is perceived by the government as an opposition university. It is significant that after the students’ demands were met, the government began to manipulate the personal tragedy of the university rector. It should also be noted that the students received support from the pro-government media (PosTV, Imedi, and Rustavi 2).

On the one hand, the government’s punitive measures are always followed by public solidarity. On the other hand, the government’s attempt to use the Russian-style tactic of favouritism along with punitive measures is obvious. How successful this attempt will be will become clear in the near future. But the fact is that the democratic future of the country will be threatened in case of the ‘taming’ of the youth.

P.S. Masha Drokova, the Girl Who Kissed Putin, soon left the ranks of the movement because of internal conflicts; she now lives in New York and runs her own company.