Author : Leila Changelia-Gegechkori

‘We live with the sadness of these memories.’

— Antoine Saint-Exupéry

I am in Anaklia, on the seashore, where the Enguri flows into the sea. There is an infinite expanse of space before my eyes. The sea is shimmering blue, so clear and calm that it reminds me of Titsian Tabidze’s* lines: ‘The sea was so calm and peaceful that I didn’t even remember if it had existed...’

In the distance, at the horizon line, hangs a huge ball, about to plunge into the sea... I have seldom seen the Enguri so clear, so transparent. It is flowing swiftly and clinging to the infinite spread out before it. It looks tired, probably it is carrying bitter news, news brought from Abkhazia, not across the bridge built over it, but across its own heart by those who came from there...

There is a sense of stillness, and I want to stay there for a while, to enjoy the mysteries of the river, the sky, and the earth.

The red ball has long since disappeared into the sea. At the mouth of the Enguri, on the bridge that stretched like a rainbow, the lanterns were already blazing, and the stars were blooming in the sky.

The full moon was floating above me, and I thought that all this looked like a temple, and the evening like a chant, but you couldn’t hear it with an ordinary ear, you had to listen to it with your heart.

This silence and mystery of the evening awakens the thoughts. The sea breeze is lingering on my face and hair—it is blowing from Abkhazia, and it seems to me that it is blowing from there especially for me... Perhaps nature understands us better than we think.

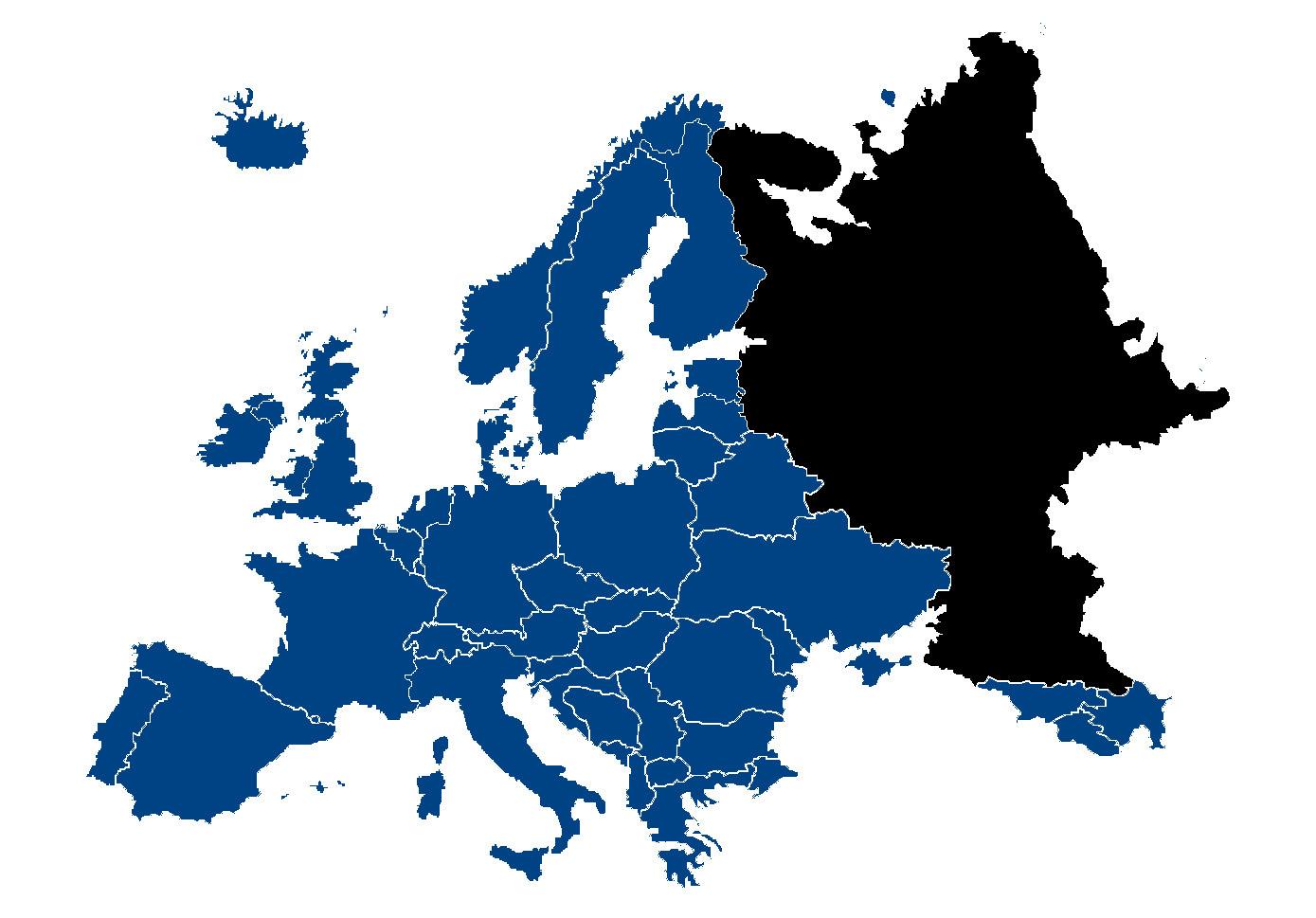

Once you cross this bridge, you are in Ganmukhuri... a few more steps and you are in Abkhazia! If you want, walk along the river and after a few kilometres, you will come to the Enguri bridge. How many tragedies, tears, and fears, how much despair and pain does it carry in itself? It connects the parts of the world separated from us and fixes the bitter reality: here and there! This side and the other side! In this and that Georgia... yes, in Georgia, we have divided it into this side of the bridge and that side of the bridge.

These words have a strange power, I feel an invisible thread linking me to my corner, town, village, sea, mountains, river, and so on. This thread flutters, and I too am trying with all my being to perceive the smell of that land, the breath of that land, the sound of that land, the land that belongs to me, it is so close and at the same time unattainable. ‘Just for a little while, just for a little while, just for a little while...’—my inner voice is screaming, but I don’t believe it anymore, because we have been patiently listening to this for 30 years, patiently wearing the terrible labels of IDP and refugee... and we do nothing, we try nothing... there are only words without actions, and we come to terms with it. And what is more—in recent years we have not heard even these empty words, Abkhazia is not mentioned anymore. Unfortunately, we have come to terms with it, we have forgiven.

My heart is beating strangely. The Abkhazian breeze makes me think. I feel as if I am drowning in a sea of memories, and I don’t want to, I don’t want to, because it is painful, difficult, even unbearable. I want to get away from it, to look at the beauty unfolding before my eyes, to just think about it, to savour it, but something drags me in like a swamp and I want to think about the past.

Despite 30 years that stand between us, what will make me forget my native places, what force will make my love disappear, but why so many years were not enough for me to forget the blood spilled in Abkhazia, the tragedy that happened there, those terrible events, why these unbearable feelings are forever imprinted in my heart? I am silently appealing to the heavens, and I do not know whether this is a reproach or just a question.

I want to evoke only warm, joyful, happy memories, but someone or something invisible controls my mind, and sad, painful stories replace each other like frames... Sometimes I think that these painful memories have settled somewhere deep in my heart, but even a light touch is enough to bring them to life.

***

Gali was not territorially affected by the fire of the first big war, but what did it matter? Terrible news came from the front, women, children, old people fleeing the war found shelter in our town. The war destroyed everything. Honest, pure-hearted boys who sacrificed their lives for love. of This tragedy is the fault of those ‘statesmen’ who loved their position more than the Motherland and acted on the instructions of the main enemy—their neighbour of the ‘same faith’. Burdened by this eternal sin, they thought neither of the country nor of the people. Their actions set the stage for this catastrophe. So many things had to be considered, thought over in their decisions and actions, since the most basic mistake could have had the most serious consequences. They did not take into account or think, but made mistakes similar to crimes... Unprofessional commanders!—What could a couple of exceptions have done?! The Right didn’t know what the Left was doing... and the result was immediate: The normalization of terrible news... strategic heights taken by selfless boys, battles won and the order of ‘superiors’ to retreat... and finally: Gagra fell... and then Gantiadi was captured. Then, Gumista, Sukhumi... battles at Kindghi... Terrible news from Kochari, Gulripshi... Blood, death, failures, displaced people, suffering, miserable people...

As I write this, it seems to me that not 30 years ago, but right now, we are standing at the end of our street, along the Tbilisi-Sukhumi motorway, watching with a strange silence, helplessness, astonishment and despair, the huge stream of displaced people flowing before us. They were fleeing with everything that could move: cars, horses, carriages, carts, wagons, on foot... I will never forget the face of a boy of 13-14 who was dragging a frail old woman, probably his grandmother, in a cart...

Can you imagine such a huge flow of miserable people on the road and still a strange, unbearable silence?! And it was obviously not the result of consent, but of unbearable helplessness. And we stood there and probably couldn’t think of anything—there were no thoughts, no ideas, just silent despair.

Looking back 30 years ago, I wonder what we were waiting for, why we did not follow, why we did not join this stream, what were we hoping for? Perhaps we didn’t want to believe in the intentions of external or internal enemies. We did not want to believe in the intentional or unintentional treason of the heads of our state. Yes, treason, because the development of events looked that way, and made us think that way. I am only conveying the emotions that people felt at that time, and people cannot be fooled… or can they?!

God, why 30 years were not enough to forget all this?—I call to the sky again and want to dive out of this sea of horrible memories, I want to merge with this river, this sea, and have only pleasant memories and images of happy days following me from there...

***

The other day, who knows how many times already, I was telling my grandchildren about Abkhazia. They are now adults in their early adolescence. The boys are from Gali, the girls from Sukhumi, but none of them has ever seen their own hometown. My children left their native places when they were 12-13 years old, Abkhazia will never be erased from their memory, but what of my grandchildren? Their generation? They have not seen this place, and if something from my narration means something, I do not know. I still repeat, tell; I want to plant a seed of love for this place in their souls... and I go on:

And then I share what I have kept in my heart and continue the pleasant story of their parents’ childhood, our house in Gali, the small garden of feijoa, barberry, and roses, our estate in Gudavi, great-grandparents, other family members, the beautiful courtyard which is 3 kilometres from the sea..., the river that flowed in front of our house, the huge garden of fruit trees, the fig alley, the walnut grove, the many pets and poultry, the melon and watermelon garden, the neighbours... I tell it for the tenth time, and they are still listening attentively, ‘We know, grandma, we know,’ they assure me, and I look at this ‘we know’ with suspicion, maybe they are listening out of politeness, maybe they don’t quite understand what I want to say. Once I read a poem by my poet friend Lali Gulisashvili and asked them to reflect upon it:

‘My son has grown up, he has already seen Rome and Nice,

He hasn’t seen Abkhazia; he hasn’t seen the blue lake of Ritsa,

Prisoners of the Motherland, Pitsunda and Agudzera,

If he has not seen Sukhumi, why does his heart beat?!

If you’ve lost even a handful of earth in your homeland,

If you haven’t seen Sukhumi, if you haven’t seen Blue Ritsa.

Then beseech the heavens,

My son, you must see Abkhazia...‘

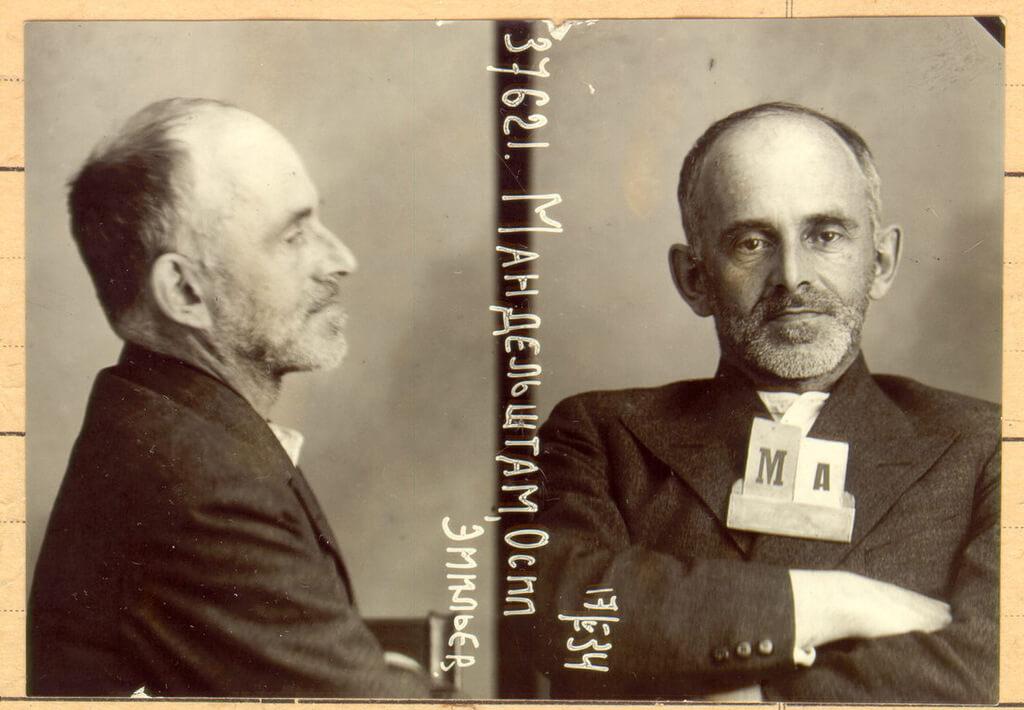

I couldn’t help but read these lines in a trembling voice, barely holding back my tears. I read in their eyes some sadness, and it touched my heart, and I also felt sorry for myself and these children, because ‘like a river, I was turned off course by the cruel and brutal epoch. My life was counterfeited, and it flowed into another channel past the other. I never got to know my native shores’—these lines of Anna Akhmatova* wonderfully correspond to our reality. I have been thinking for a long time about Georgians living abroad, about their children and grandchildren, including those who left for foreign countries and other shores as immigrants. I fill the title page of the Georgian books I brought to them as a gift with inscriptions, and it ends with these lines: ‘Who gave our homeland so many children as to doom them for staying abroad!’

***

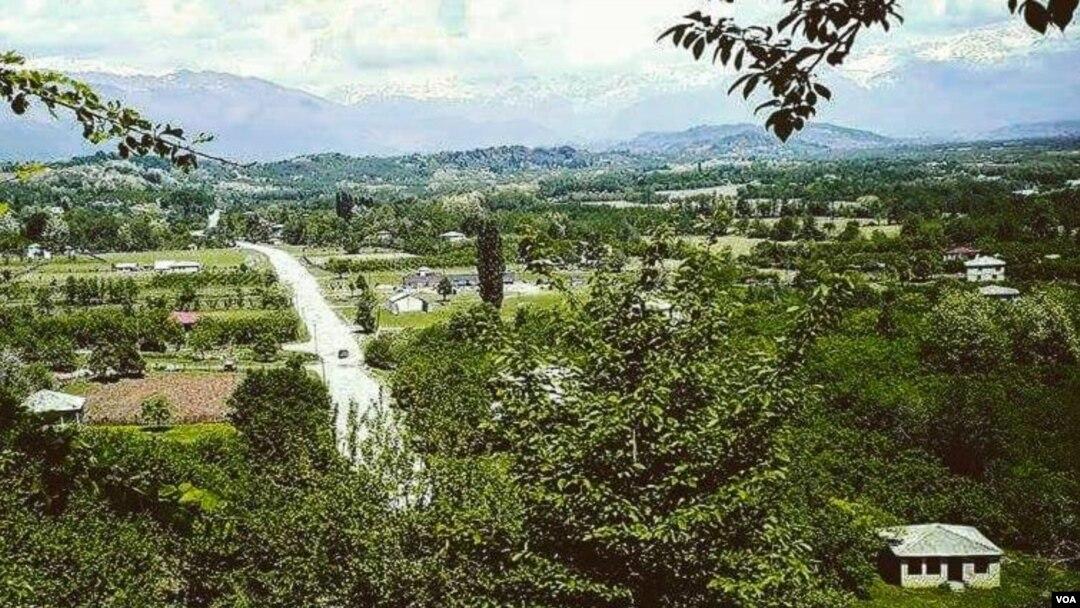

One day, a former neighbour from Gudavi came to visit me. I had been sneaking through the forests and I had snuck into our village, I couldn’t resist, she told me. The roads of the village had turned into a forest of thorns, I could hardly reach home. Without us, without our voices and noise, the fruit trees have become degenerated, wild. Your Gulabi pears look like forest pears, your select apples like wild apples. Your peaches and figs are shrivelled, their colour faded. She also showed me pictures taken on her phone—Look here. They are waiting for us; everything is waiting for us. My heart sank, it was hard for me to look at these pictures. So, I wrote in my diary:

Navigating the thicket, the path to our river eludes,

Only lizards, nimble, dart among the thorned barricades.

A spider, diligent, weaves its web outside my window pane,

While fruit trees, once vibrant, now withered, lost to time’s refrain.

The trees stood with their wings clipped, lonely, looking sadly at the fallen, degraded rotten fruit, and thinking of those children who should have filled the place with life and joy, and their footsteps should have prevented the weeds from growing... the weeds! How comfortable they felt, how they had taken over the place.

Having lost its course, our river has dried up, its banks overgrown with thorns. The silhouette of the burnt house showed the head of a fireplace and a tkemali tree leaning against it. It has grown so much that it almost reaches the sky. Perhaps it grew from a bone dropped by a bird; how much hope it had before it became a tree. From there it overlooks the courtyard, trying not to miss anything, waiting for us, the hope of our return giving it the strength to live. The water well looks pitiful, the top has disappeared into the weeds, it has covered itself with grass to hide its pain, it has become inaccessible... the silence is broken only by the screams of jackals... Eh, I guess the sun doesn’t shine there like it used to.

Meanwhile, the moon becomes even fuller, the starry sky is looking down at me like the dome of a cathedral, and I want to ask it to tell me today’s news of Abkhazia, because it is looking at those places now too, isn’t it? It keeps silent, and the moon floats away, as if hiding behind a white cloud.

I couldn’t dive out of the sea of unwanted memories. I remember the September 25th, our last meeting in the teachers’ room of my home school, No. 1. None of us looked like ourselves, as if we were at a funeral. There was an unbearable silence; uncertainty, fear and despair were the central features of that meeting. It looks like treason—why did they return the population and the students to Sukhumi? Why did they send our army away from there; when we were promised that it was over, what was that! Did they really send people back there to be slaughtered?—someone asked, but the question was rhetorical, no one had an answer. The silence became more unbearable than the whistling of the bullets...

It looks like a treason—why did they return the population and the students to Sukhumi? Why did they send our army away from there; when we were promised that it was over, what was that! Did they really send people back there to be slaughtered?—someone asked, but the question was rhetorical, no one had an answer. The silence became more unbearable than the whistling of the bullets...

Sukhumi fell in two days. In the next two days Gali was abandoned. Can you imagine—our army was moving ahead, and the population was following it! Abkhazians celebrated on the Enguri bridge...

***

I took refuge with my parents’ family in Tsalenjikha. My mother was from Gali, and all her relatives, the families of her four siblings, my sister’s family and mine, plus the closest relatives, found shelter there under the status of ‘displaced persons’. In addition to our hosts, there were 37 of us, sometimes more. We tried to take the joy of surviving, of getting out of the impending disaster, of moving forward, not thinking about the lost corner, the native hearth...

It was difficult, very difficult! Our situation was complicated by the fact that the Mkhedrioni* detachments were camped in the centre of the village, in the House of Culture. They were just a stone’s throw away from our house. How they terrorised the village is a separate question. They did not spare us either, often coming to us with ‘requests’ for food. Who would dare refuse? Did the family that readily accepted so many displaced people have time and energy for them? Power decides everything. They ‘did not remember’ about Tsalenjikha, Anaklia, Darcheli, Kakhati, and Samegrelo in general, which they had burnt down earlier, because they were there by order of the government, they would sometimes ‘explain’ to us. I remember how we would gather in front of the TV in the evenings, eagerly waiting for the news, but... there was no hope, no responsibility towards the displaced people, and we still clung to hope. The news would come from somewhere: we are returning in two months, no—in three days, before the New Year. So, whether it was true or false, this clinging to hope saved the displaced population. Otherwise, if we knew for sure that 30 years would pass and still nothing would change, would we have been able to bear it?!

However, our evenings in front of the television went on, followed by ‘political debates’. Men took it more painfully than women and children. After yet another hopeless news item, they would wave their hands in frustration, shrouding themselves in clouds of tobacco smoke, running away from themselves.

Soon the murder of President Gamsakhurdia finally collapsed the tower of hopes connected with Abkhazia.

It is not a civil war, but a plague, an incurable disease, our men once concluded. If you’re the head of state and you can’t manage the country, if you can’t stop the bandit groups, if you can’t do anything for the good of the country, then you’re not a politician—our men rendered the final verdict on Shevardnadze and decided that from now on they would no longer watch parliamentary sessions or hold domestic ‘political debates’.

On the Zugdidi-Tsalenjikha Road, near the village of Chkaduashi, there is an elevated hill from which the villages of Samurzakano along the banks of the Enguri River can be seen as if in the palm of your hand. I remember how our men used to say: ‘When we were travelling from Zugdidi, we would stop the car there, stand and look towards our homeland for a long time... May those who brought us to this be cursed.’ The women would sigh, trying but failing to stop their tears.

Two years passed. Life went on in its own way, demanding its own course. In our large family (with whom, as I have already mentioned, 37 IDPs were living in addition to the hosts), the oldest grandmother was 82 years old. One day she told us: ‘Don’t even try to talk me out of it, I am nearing the end of my life, I have to go back to the house I built, I have to die there. I have thought a lot about it, I can’t change anything... how can I let my mother go alone,’ said the elder uncle, his brother also supported him. No one tried to stop them, it was pointless. Before leaving, the uncles told us: ‘We will protect our house and property, we will not let the hearth get cold in spite of the enemy, even if it costs us our lives. Now we are strong, not through physical strength, but through the strength of our spirit,’ they added, and returned to Gali.

In the evenings we would traditionally gather in the big room and often talk about them. One day I was asked: ‘We know that you have something written about them, so read it to us.’ I still remember how attentively and with saddened faces they listened to the passage from my diary: ‘...When they returned home, they found the house and estate looted and devastated. “The main thing is that it isn’t burnt down,” they must have thought, and quickly walked round the estate and the endless mandarin and orange orchards. April had taken possession of the orchards, the citrus trees, peaches, tkemali and apple trees were adorned with fragrant blossoms. Drunken bees were buzzing... Cyclamens, violets, and snowdrops were blooming at the foot of the fence. The weeds wanted to choke them out, but in vain. There was spring and life all around, and that was encouraging. Soon they ploughed the field with the help of a horse and plough they had somehow found. They felt surprisingly brave... From the garden came the smell of fresh earth. The corn kernels scattered across the ground like pearls, laughingly hiding among the furrows. Encouraged, they exposed their heated foreheads to the fragrant breeze.’

Soon, the aunts announced to us: Our men are there, not only the house, they also need to be looked after (this was presented as a special argument), and the time for our return has come. It was pointless to resist this time either. They happily returned home, leaving their children and grandchildren on this side of Georgia...

In 2001, the eldest member of our large family, my grandmother, died. Back then it was still possible to go to Abkhazia, at the cost of risk, of course, but still. Back then, only Abkhazians stood on the bridge at the checkpoint. You could talk to them. It would happen when someone wanted to go to the funeral of a relative or to transport a deceased person.

I will leave tomorrow morning—my mother announced. We are also going—my father responded and looked at us. By chance my arrival coincided with this news, I left the children in Tbilisi. I decided not to tell them anything, but I wasn’t worried about the risk either. They were already orphans, what was the point of worrying (my husband had died in the war in Abkhazia).

Let’s go to the Enguri Bridge and see what happens, if anything, I’ll cross alone, said Mum. It was our first (and last) return in 8 years. Of course we were scared, but we couldn’t do without mourning our grandmother.

We crossed the Enguri Bridge peacefully. They took away our passports, you can stay until the evening—they explained to us. If you take anything with you, you will have to pay a customs duty, —they added. The taxi driver turned out to be Abkhazian. A wave of fear passed through us, as we looked at each other. Do not be afraid, I do not hate Georgians, I am not your enemy—I could not believe my ears, he spoke in Megrelian. I know Georgian too, I graduated from a college in Tbilisi. You and we, ordinary people, have nothing to do with it, governments deceived us, it is their fault, and we have to do something about this disaster—he said. He had an Abkhazian accent. Our eyes met in the interior mirror of the car. In his eyes there was sincerity, in mine, fear. Don’t be afraid, sister, calm down—he said, turning to me. Tears came to my eyes.

The car was heading on the road towards Gali. I was heartbroken by the empty roadside villages, and the burnt houses that seemed like an unhealed wound on the earth. I still had a few hours left until evening. I said—I need to go to my house if only for a few minutes, I need to walk down my street. A few people could be met along the way. There no longer existed the town I knew. The emptiness was depressing. Burned down, and destroyed was my secondary school No. 1. I stood by it for a while. I mourned the happy years of my youth there, the childhood of my children, their friends, and my former students. I walked down our empty street, with its burnt-out houses, and yet I was filled with some kind of feeling as if I had just finished my lessons and was rushing home.

My house was ransacked. All the furniture was taken, it seemed they didn’t need books for anything; they were scattered all over the house, lying on the floor. I found a table lamp in the children’s room, I remembered what my daughter had said—I wish I had been given some item from the house, it would bring back the warmth and wonderful memories of the place.

From the books I took The Land of Men and The Little Prince by Exupéry. I remember my children were very fond of this writer. I also took a tablecloth and my mother-in-law’s little old sewing machine. ‘These things decorated the house and were full of memories’. I remembered the line from the book....

Back at the checkpoint, we had to wait. The person who was supposed to return our passports had gone somewhere. People with automatic rifles moved around us. There were many of us waiting for our passports. I don’t know how I dared, but on the pretext of the passports, I talked to one of the guys with an automatic rifle. He was about 18. I looked at the rifle, the questions seemed to be written on my face, I think he understood and explained that he had been drafted into the army. There was timidity and even regret in his voice. Can you kill a man?—I asked. No, how could I?—he replied in surprise. The answer was at odds with the reality of the situation, but I couldn’t question his sincerity. You seem like a good person—I said, holding out my hand. We walked a few steps. I said—I have children just like you, they were born here, and they miss this place very much. I was surprised, he looked at me as if he were the only one to be blamed. Let’s shake hands, we’re not enemies—I said, holding out my hand. My name is Bekir—he replied (we were speaking in Megrelian). I don’t hate anyone; I have just been drafted into the army—he added. Maybe we can do something and reconcile. My grandfather thinks so too—he replied. I wanted to hug him, but I was afraid of the men with guns. Meanwhile, our passports had been returned to us. I only looked back once. He was standing there watching us. I waved my hand, and he waved back.

22 years have passed since this story, I don’t know what Bekir and his grandfather are thinking now, but it is obvious that the ice between us has not broken.

I often think about my relatives who left their children beyond the border in Georgia and came back. Now no one lives in their houses! And time is playing into the hands of the main enemy, and the gulf between the divided parts of our world is gradually deepening.

Homeland is not just beautiful mountains and hills, people give it life, breath, thoughts... and it is ‘a knot of connections, and only connections matter most’, so it is not lost yet, the path that connects this Georgia and that Georgia still intersects, the path that goes through people’s hearts, and although it is covered with moss, it is still a path, it still exists, it is still visible.

Georgia on the other side is silent. It does not say anything about Abkhazia. Only here and there on the Tbilisi-Sukhumi Road, there is a stencilled inscription: ‘Remember Abkhazia!’

Remember Abkhazia and nothing more?!

* * *

Meanwhile, the moon had slipped out of the clouds and was now hovering over the bridge, growing brighter and shedding more light on the place. ‘The moon was like the sun,’ a poetic image from a folk poem came to life. The Abkhazian breeze was still with me. How much time had passed, I thought. My favourite writer helped me to soothe the heartache brought by memories: ‘The main thing is that everything that was in the past still exists somewhere, customs, family holidays and a house that keeps memories... the main thing is to live for the return!’

Leila Changelia-Gegechkori

Teacher of the Georgian language and literature at Gali secondary school No. 1 ‘Shota Rustaveli’ (I can’t ‘squeeze’ the word ‘former’ somewhere here).