Author : Giorgi Antadze

The public know Giorgi Antadze as a successful Georgian pharmacist and entrepreneur. He is also an unrivalled connoisseur of classical music, especially Italian opera. But Giorgi Antadze’s true passion is travelling. Few Georgians have travelled the world like him. But Giorgi’s travels are not so much about crossing latitudes and longitudes as they are about visiting known and unknown places, constantly striving for discovery and savouring the pleasure of knowledge. Each of Giorgi Antadze’s journeys are like an adventure book, full of funny and sad stories, lyrical journeys through time, reflections on the collective self and the future, driven by an innate, stubborn optimism. And since one of the main missions of New Iberia is to promote the importance of civic memory in Georgian society, to understand or rethink the ancient and modern history of Georgia, we present a new column by Giorgi Antadze: ‘Notes of a Traveller’, which should be of particular interest to our young readers.

Zaza Bibilashvili

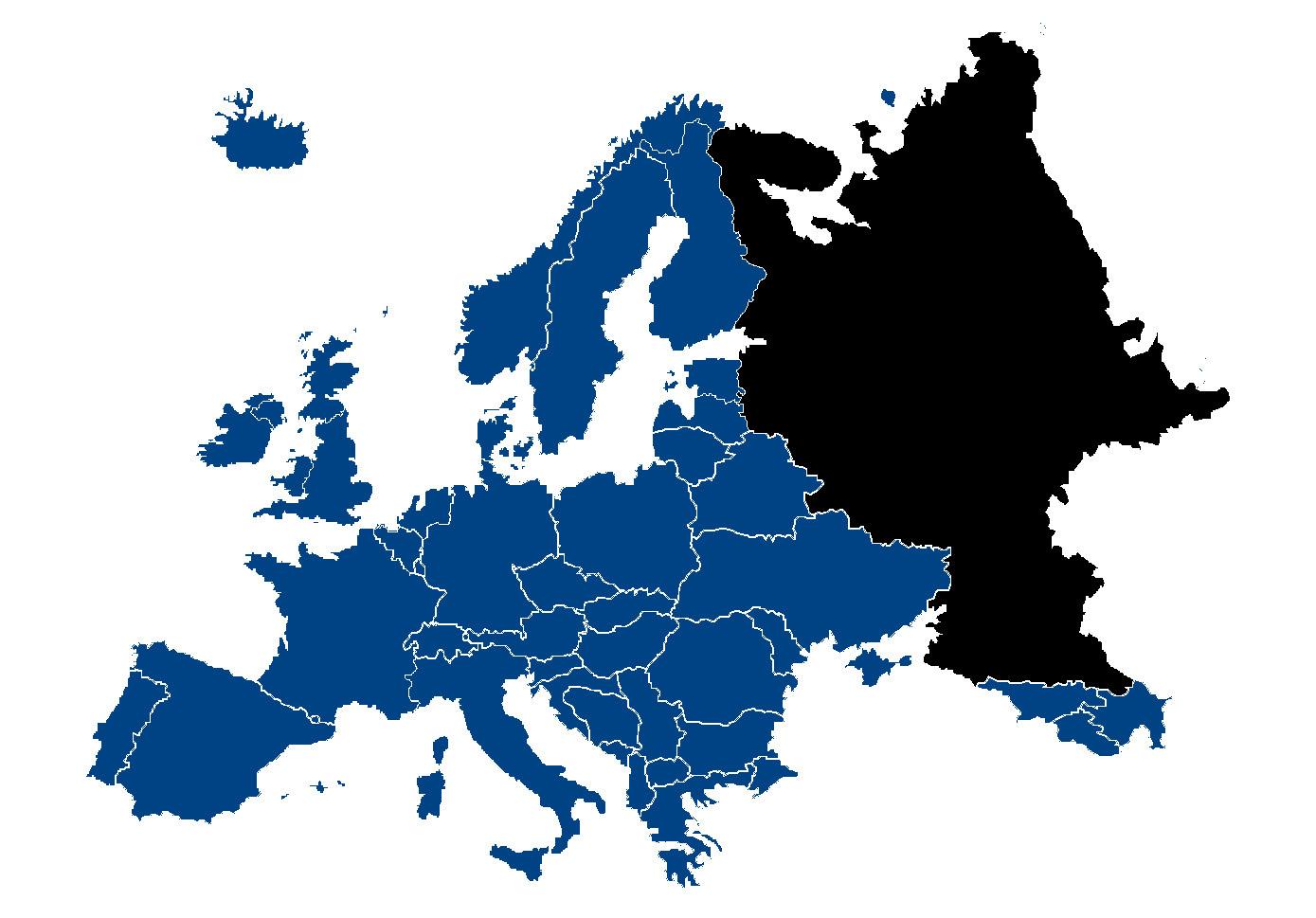

There was a time when those stuck behind the Iron Curtain watched only one TV programme where a reputable explorer-traveller shared his impressions of the odyssey of Thor Heyerdahl or Jacques-Yves Cousteau. In those days, only party members, dancers, and athletes travelled to ‘capitalist’ countries accompanied by agents of the KGB, the Committee for State Security. And we, representatives of the lower class of a classless society, unlike party members of the same society, for trips to ‘Kislovodsk’, bothered our relatives, acquaintances, and friends cosily ensconced in trade unions.

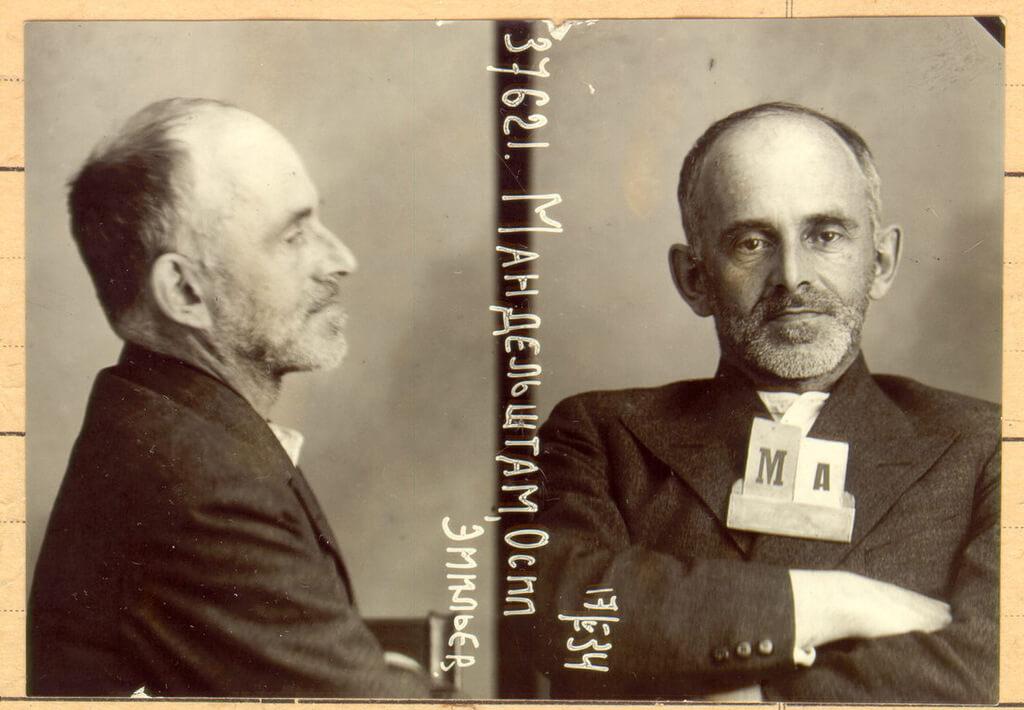

I will refer to Tolkien’s world and make this comparison for a generation to whom the Soviet Union is an unfamiliar fruit: Behind the Iron Curtain was Mordor, beyond it was the Shire, the domain of the hobbits, and far, far away, across the ocean, was the kingdom of the elves, Valinor, with its magical American dream. This dream was fuelled by my grandfather’s old radio, which every evening, at one o’clock in the afternoon, with its deafening hiss and crackle, told us marvellous stories about the kingdom of the elves. I remember my grandfather’s attempts to somehow catch the desired wave that carried the flavour of freedom. I remember the joy that followed the coveted phrase: ‘This is the Voice of America from Washington, D.C., with Khuta Poteli at the microphone’. Our elf-like pointed ears would strain up, and I remember my grandfather’s response, which he repeated every night: ‘I know Khuta Poteli, I know his real name, but I can’t tell you that secret.’ The phrase was full of conspiracy as if he really possessed the Isengard secret. As if he didn’t know that the KGB had long since deciphered ‘Khuta Poteli’ and ‘Leo Lechkhumeli’, and that a senior KGB officer living behind a plastered wall had even recorded information about the column we had managed to listen to, despite the forest of radio-jamming towers that had grown up around Lake Bazaleti, resembling Fangorn Forest.

The Lord of the Rings was on the list of forbidden books in that Mordor, and naturally I knew nothing about it. Only now, many years later, when I have visited Tolkien’s fairytale world, I see one thing in those distant memories: Grandfather was the real Gandalf, first grey and then white. It was he who shared with me the knowledge that there was once an independent Georgia, that the Soviet Union was one big prison, and that outside that prison there was a world where people felt happier. This world was out of his reach, and it was then that I felt an insatiable craving to break out of this prison. At that time, no one could have imagined that in a few years, the castle would collapse and we, like bats startled by the light, would fly out into the rest of the world, which was sleeping peacefully, unaware of the cave in which a part of the human race, living on one-sixth of the planet, had spent 70 years.

Ceaușescu and the Football World Cup

I learned that the train is a comfortable mode of transport only when I first travelled by rail from one German city to another. Before that, I had considered the rustle of green carriages and the unbearable metallic creaking to be an indispensable attribute of a train journey. The rhythmic clattering of the wheels had its own romance; I still love the strong smell of railway stations and never felt uncomfortable about having to spend a night on the top third shelf of a platzcart carriage.

The longest for me was a several-day trip when I crossed the USSR border for the first time and visited socialist Romania with a group of students excited by a special Komsomol trip voucher. At the border they were changing wagon wheels, and the leaders of the Avaz football club noted with trepidation that the difference in gauge was an ingenious decision by Stalin to prevent military echelons from quickly invading the USSR in the event of an enemy attack. I don’t know the real history of this technical ‘find’, but in that era, perhaps the West should have been more grateful that Soviet armoured trains would have been delayed at the border in the event of hostilities.

The political climate of the time was saturated with the smell of nuclear ‘gunpowder’ and the fear of a war of extermination. From this perspective, it is understandable that we were much further away from world war than we are today, although crossing the border was more like breaking through the front line. The world had split in two, and our train rumbled along as if it were actually drilling through the Iron Curtain with a Soviet-made bit. No one in the group was as ‘poisoned’ by Western propaganda as I was, but no doubt everyone subconsciously felt that we were about to experience something completely new, and we were preparing for it inwardly.

It was as if the colours of Bucharest created this impression. Then we saw for the first time the automatic street scales on which everyone could individually measure the force of gravity for coins, and here for the first time the Georgians outsmarted the European scales and managed to weigh the whole group for just one coin. Our ‘ingenious’ finding was that before the first Georgian to be weighed came down from the scales, the second one climbed on, then the first one went down, and the scales recorded the weight of the second person and so on. One coin was enough to make us feel like real heroes and giggle heartily over our share of violations of the European order.

That year the FIFA World Cup was held in Mexico. Group tournaments were not broadcast in the Soviet Union, and we could only watch the championship from 1/8 finals onwards (except for games involving the Soviet Union national team). At that time, travelling abroad and watching matches throughout the tournament would have been a great blessing, if not for one unexpected detail: We soon learned that in Romania, which was poorer than the Soviet Union, in order to save electricity, the TV was switched on only from eight o’clock in the evening and only for four hours, most of that time being taken up by news and propaganda. As for football matches, we could not even watch the finals on television, let alone the group tournaments. The God who helped Diego Maradona score a goal with his hand in the match against England was clearly not favouring us. And what was God supposed to do where Nicolae Ceaușescu was the boss?

However, an interesting story happened to us near the Cathedral of God: The parishioners gathered in the courtyard of the cathedral, when they heard of our origins, with great honour invited us to a set up table and with sincere affection told us the story of Antimoz Iverieli (Anthim the Iberian). We were told of his service to the Romanian Church and State, the latter account being laden with a sense of great repentance, and it was revealed to us evasively that, as Wikipedia informs us today, ‘the assembly of bishops condemned Antimoz and excommunicated him’, having declared all the clergy ‘devoid of decency’. But it was not enough for the king to depose Antimoz Iverieli as the Hungarian-Wallachian Metropolitan, he managed to finally exile Saint Antimoz to Mount Sinai. The faithful and loving Metropolitan of the Romanian people was taken out of the city in the middle of the night, for fear of unrest among the people, but Antimoz of Iberia did not reach Mount Sinai. Not far from Gallipoli, on the bank of the river Dulcea, which passes through Adrianople, Turkish soldiers captured him, killed him by cutting him into pieces, and threw his holy relics into the river.

What kind of Georgians would we be if we were surprised at such an end for the father of the nation, but we were overwhelmed with a sense of pride. It seemed to us at the time that we were all ‘Iverians’... all except one member of our group, who later probably discussed in detail with his KGB handlers who Antimoz Iverieli was—an emigre dissident or counter-revolutionary.

I realised I was being ungrateful when I complained about God’s grace. True, we did not see the ‘Hand of God’ Maradona, but what did that have to do with the fact that we overcame and survived: That spring there was an accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. For a long time, Soviet propaganda carefully concealed the scale of the disaster, which claimed the lives and health of thousands of people. Our train also travelled through areas saturated with radioactive clouds from the east coast of the Black Sea through Kyiv to the west coast. Particle physics is not without its paradoxes, but one of the paradoxes could be that, despite such a dangerous route and the enjoyment of the sea waves close to the epicentre of the disaster, none of us received a significant dose of radiation and the journey did not affect our health (apart from a few limbs we injured playing football in the sand).

Now that so much is known about Chernobyl and an excellent series has been made for Netflix, it is no longer difficult to understand the scale of the disaster. In 1986, though, when I first broke through the Iron Curtain and travelled to a poor but still foreign country, I was thinking about something more than those invisible and deadly rays: How to organise my life so that, like gamma rays, I could pass through any Iron Curtain unhindered. It would take only three years and a quantum leap in history to make my dream a reality. Exactly three years later, I would also see images on television of the hand of the revolution executing Nicolae Ceaușescu against the wall. In Romania in 1989, many people, perhaps motivated by revenge, celebrated the execution of the dictator, and to tell the truth, somewhere deep in my heart I was moved by the sincere surprise of the tyrant and especially of his wife, and the question stuck in their open eyes: ‘What for? We have done so much for you?’ After all, dictators sincerely believe in their own mission, and surprise freezes on their faces when they see the bullet fired by ‘ingratitude’.

You are the Vineyard

The impressions of European travellers when they had to communicate with the aborigine tribes of distant lands are often described. There are not many stories of civilised people being surprised by a visit from barbarians. I can think of King Kong only. But this clash of civilisations—seen from both sides—is quite interesting. The Soviets’ visit to Europe caused as much of a stir as if a group of cannibalistic tribespeople from Papua New Guinea had come to dine at the Café de Flore. In their eyes, we were still exotic—aliens infiltrating through the Iron Curtain. Exotic is good, but we didn’t really realise or care that everything in Western civilisation has its limits.

The chronicler has not preserved this detail, but I am sure that wherever Vakhtang VI’s entourage stopped on their way to Astrakhan, be it a tavern or an inn, they would start singing Georgian songs. This tradition, which has turned into an instinct, can often be observed today in various airports around the world. There are many videos on YouTube where proud Georgians standing at the piano in the departure lounge surprise transit passengers with polyphonic folk songs. I am more amused by the bewildered faces of the latter: They are at a loss as to whether this is a flash mob, a film shoot, or a performance by street musicians for which they have to pay?

In short, although I do not sing, I also became a participant of one such performance at the early stage of introduction of European civilisation to Georgians.

In the 1980s, Poland was already seen as the vanguard of freedom-fighting Eastern Europe. Solidarity had become an invincible force, and Lech Wałęsa was the leader of the anti-Soviet movement. ‘Oh God, God, that sweet voice...’ It rang in my ears like a bell and, of course, going to Poland at such a time was a doubly happy event. But freedom is freedom, and a traveller needs currency to be happy. To obtain local currency, only one thing could be used from the Soviet wealth that can be counted on the fingers. Just like now, the economy of Russia at that time (the same USSR) was based on the export of four resources: oil, gas, minerals, and... caviar (to be fair, it should be noted that during the Soviet period this was not the case, and then a fifth element was added—export of prostitution). Of these four resources, we, Soviet tourists, could get hold of only caviar, and we stuffed our suitcases with canned red caviar, for which polite Polish maître d’hôtel would eagerly pay 10 US dollars apiece.

The Georgian students, thus enriched, naturally went to the best restaurant in Krakow. Having exchanged the caviar for a European dinner, we walked through the quiet night streets on our way to the hotel. It was very late, and we were incredibly surprised to see several bars open on the way, so we decided to continue our drinking in one of these semi-basement bars.

As I wasn’t singing, my eyes were open and I was the first to look around the hall. The small round stage in the middle of the hall and the shiny metal pole towering above it looked suspicious, but how could I have imagined that we ended up in a place we had never been before? And indeed, we entered during a break when the performers were relaxing backstage. This is what European delicacy is all about: We were not interrupted while singing, we sang until the end, and only then loud music started to play, and the ladies started to dance around a metal pole.

After all, it was our first time and I’m sure the guests sitting at the other tables were also for the first time in a strip club where Georgian chants were being sung.