Author : Gia Japaridze

Diplomacy, at first glance, is a routine activity; one realises one’s abilities only within the context of the tasks set by the Foreign Ministry. It means living within a framework of bureaucracy and etiquette, and this life does not leave much room for freedom. Georgia aside, in the rest of the world, only people interested in politics and international issues go into the diplomatic service.

But even routine activities can leave special feelings, thoughts, experiences, and memories. My interaction with the diplomatic service for about ten years was exactly like that—it was a short journey through history, time, myself, the past, words, stories, where it is difficult for you to define the border between truth and fiction, and you don’t even want to.

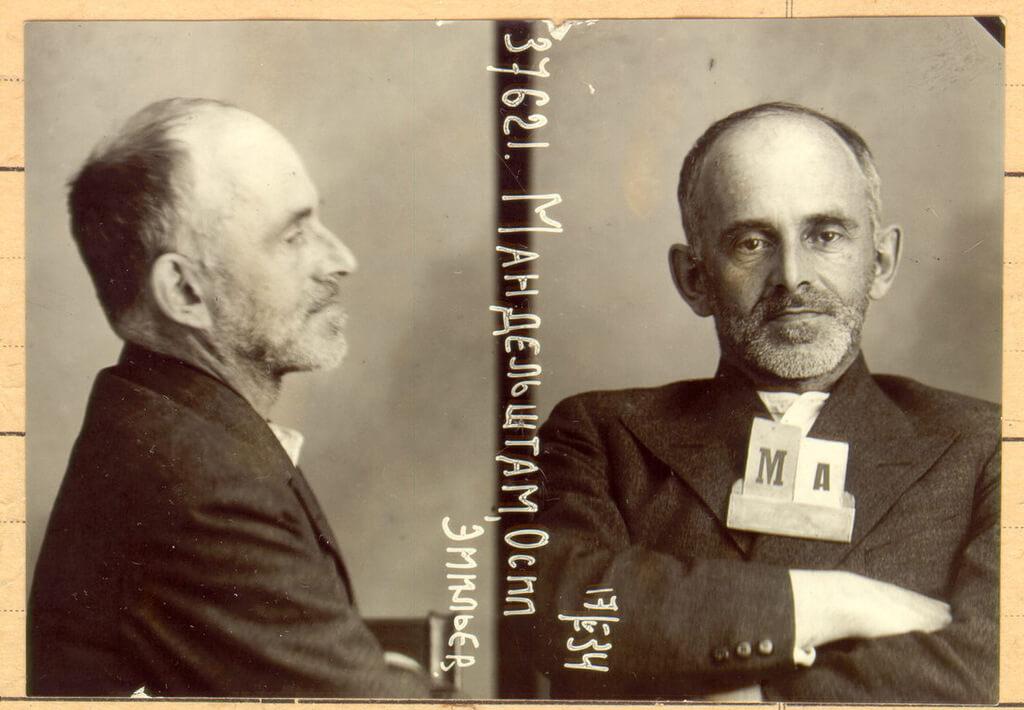

It was a journey into an old profession—philology, a love of words, sometimes accompanied by a sense of the historicity of the moment and the ineffable emotion associated with it. Someday I will try to write it down, but before that, I will tell you about it.

One episode of this journey that stands out among the others is my first visit to Mount Athos, the Holy Mountain. I do not know exactly what brought me there—destiny, which I do not believe in as a matter of course, or philology, an old profession that taught me a lot about ‘man’s word’, or the then profession of diplomacy, within which a very delicate task had to be carried out.

This journey connected me to invisible threads, not only to the people with whom I visited the Holy Mountain and saw two of the monasteries—the Iviron Monastery and Xyropotamou Monastery—but also with the people who used to live here many centuries ago who were preaching, writing, translating, and shaping the future of Georgia. This journey restored my connection with my ancestors; the connection between Georgia’s past, present, and future.

Many have heard and many have read about the unique centre of Georgian culture, the greatest representatives of the Georgian literary school of the Middle Ages, but few have realised that the Georgian monks scattered in various monasteries on the Holy Mountain, in the Iviron Monastery of Athos itself, the brilliant philologists, theologians, and translators who worked there, shaped our cultural identity and participated in laying the foundations of the absolute monarchy of medieval Georgia.

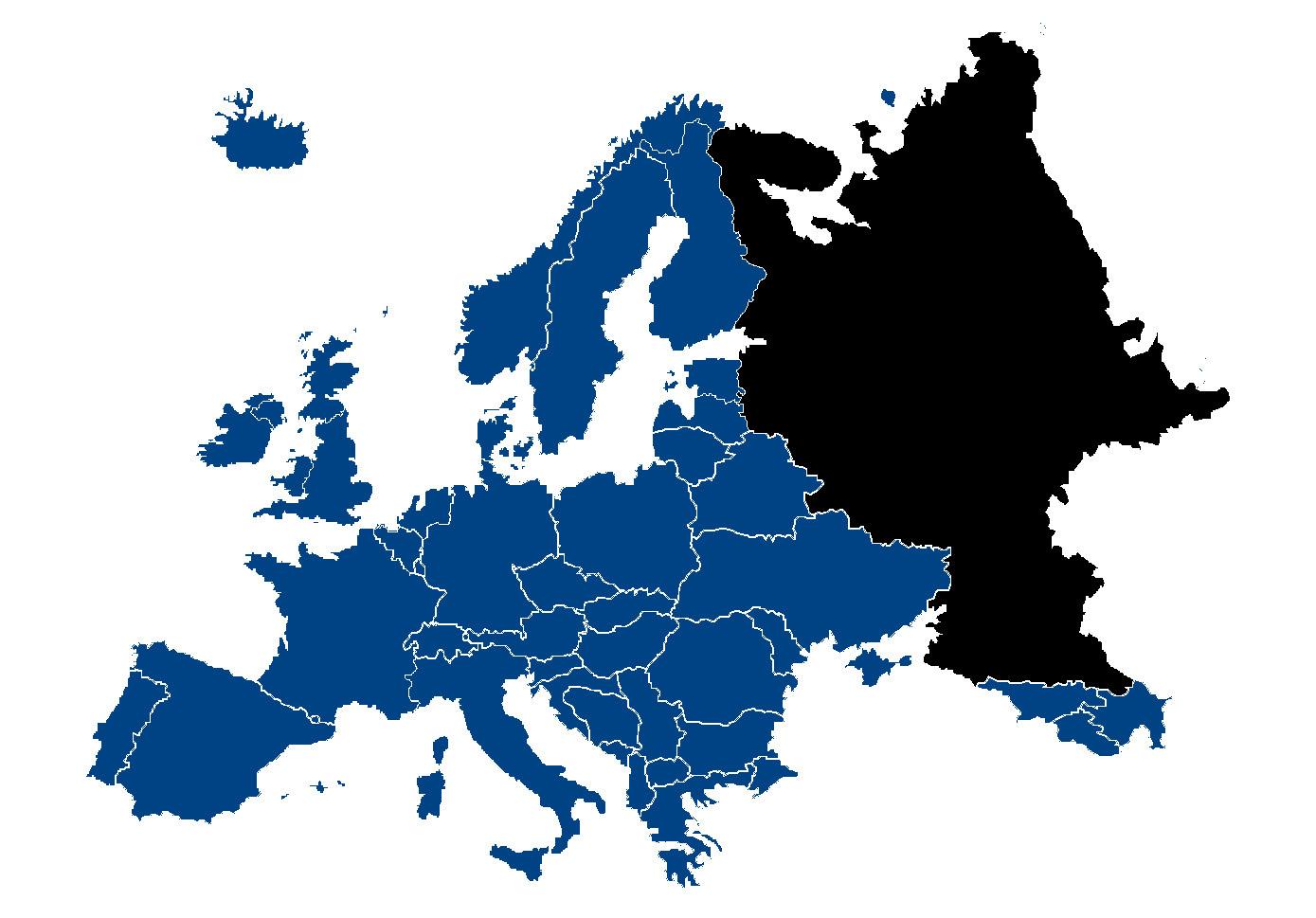

Few have grasped the political history of Georgia critically, without mythopoetics, scientifically and academically, without narcissistic heroism, dryly, in a broad geopolitical context, considering historical transitions. However, this understanding further enhances the role of the Georgian philologists of the Holy Mountain of Athos in Georgian political history. The armour of Tornikios, preserved in the Iviron Monastery, seems to convey the tragic history of our relations with the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. Mount Athos is a living testimony of Georgian-Byzantine relations. Four Chapters translated by Ekvtime of Mt. Athos indicate our European identity and value choice, belonging to the space of Western civilisation.

At the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries, the geopolitical situation changed in such a way that the creation of a powerful absolute monarchy in the South Caucasus, united under the Georgian ethnic sign, became possible. Davit Aghmashenebeli is the crown and main creator of this process, but reaching this stage was conditioned by many factors, including the activity of the Georgian party at the Byzantine imperial court and the presence of Georgian cultural-religious centres scattered in different parts of the Greek-Orthodox Empire of Eastern Rome.

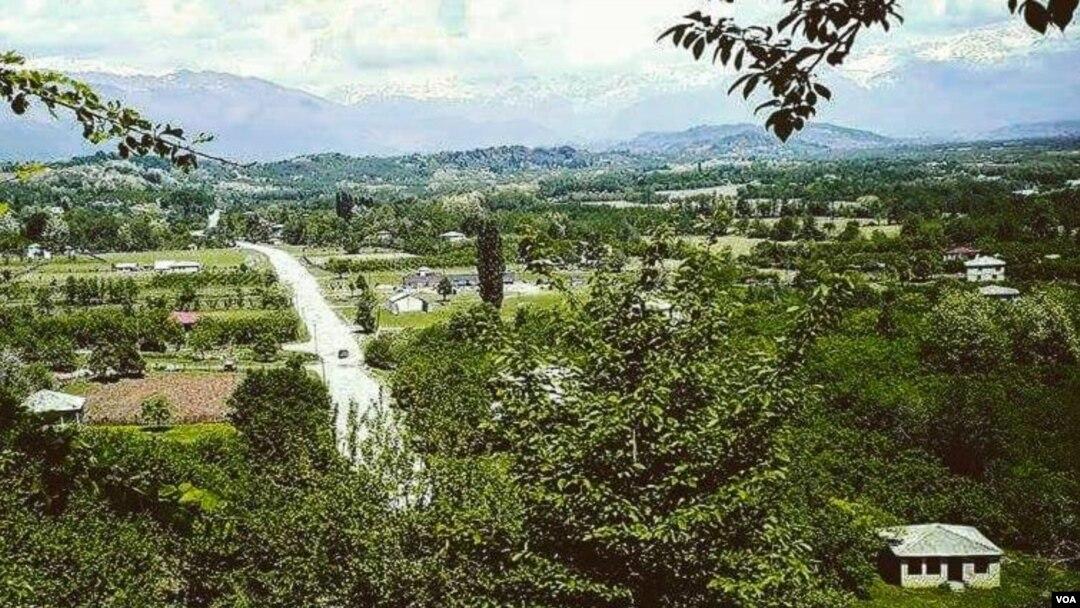

I went to Athos with the Georgian ambassador to the Hellenic Republic, Sandro Chumburidze, and his son Tega, a schoolboy at the time. The trip started from Athens. We drove to Uranopolis, a small town on the peninsula of Halkidiki (Chalcedon). Uranos (ουρανός) means sky/heaven in Greek, and polis (πόλις/πόλη) means city. The celestial city is the gateway into Athos; from here only ships can go to the monasteries; here, at the Pilgrims Service Centre (Γραφέιο Προσκιντών), we obtained the document for the right to stay on Athos for a limited time. This is a kind of visa that allows you to enter the monastic community of the Holy Mountain and stay there for a certain number of days.

For an ordinary pilgrim, this is permission to enter the Holy Mountain, but for a pilgrim of Georgian culture, it is a ‘visa’ to our history, the right to approach and touch our ancestors.

There are many stories and emotions to be told from a few days’ visit. The Iviron monastery is quite a large complex. In a small church to the left of the gate, the icon known in Orthodox Christianity as Portaitis (Παναγία Πορταϊτισσα), the icon of Our Lady of the Gate, is enshrined. In Georgia, this icon is thought to be Georgian, but in reality, it is Byzantine, and it is connected with the name of the Georgians who worked on Mount Athos with a beautiful history.

Portaitis easily impresses the faithful with its history and beauty, as evidenced by the jewellery, gold, silver, and other valuables that adorn the icon, left behind by pilgrims, probably in religious ecstasy.

The door of this small church is usually locked, the key being kept by a monk who opens the door briefly several times a day.

The door of the book depository of the monastery is always locked and the key is given to one monk, who opens the door on a special occasion—this special occasion is the blessing of the abbot. The book depository preserves a part of Georgian history, most of the manuscripts kept there are Georgian, some of them written by Ekvtime and Giorgi Mtatsmindali, as well as other Georgian monks who worked on Mount Athos. Manuscripts require special storage conditions, and the manuscripts are kept in the library of the Iviron Monastery along with documents of the Georgian kings, flags, and other objects. The European Union is responsible for the maintenance of the Iviron Monastery and the entire Athonite monastic complex. Everywhere I went I saw a banner stating which EU fund was financing the restoration and conservation of this or that monastery, who was responsible for the work and when it would be completed. This is how the European Union takes care of the Byzantine cultural heritage.

It is impossible to describe the anticipation and mood a philologist feels before visiting a book depository. What I had heard from my childhood, what I had read and then studied as a student, what my professors had talked about for countless hours, what seemed like an unattainable dream of seeing in Tbilisi, was about to come true. I was frightened by the rapid beating of my heart, with each new beat I thought it would be the last, and the anticipation was killing me. Bad suspicions grow in a man who is close to his goal, and I also was thinking, what if the abbot of the monastery had not given us his blessing? Sandro was worried too, and we told each other that we both experienced similar pessimistic thoughts.

From the first moment we met the Hegumen, our doubts were dispelled. He was a highly educated young Greek man, well versed in history, theology, philosophy, and politics, who showed amazing kindness to his guests, to Georgia, to the Georgian Church and to Georgian culture. During the meeting I often thought: I wish that at least a small percentage of the Georgian population understood Georgian statehood and Georgian history as well as this man on Mount Athos. The Hegumen’s face, cleared of worldly worries and passions, radiated an amazing serenity.

We received the blessing, and after a sleepless night in Xenon, the morning service (which begins at four o’clock) and the meal, the three of us stood at the door of the library at the appointed time. Before the arrival of the librarian monk, time seemed like a century; this distance of time separated me from the past and at the same time brought me closer to it.

When the door opened, the Gospel in the translation of Ekvtime of Athos appeared first, while Georgian flags and Tornike’s armour could be seen at the end of the hall. When I remember that moment, I always get goose bumps, my consciousness enters another dimension, and I am overwhelmed by indescribable emotions. The history of Georgia comes alive before my eyes; people awaken, as if I could witness their movements and actions. I see what I have studied for years, what I have read before—what existed for me only as a myth, something with which my time in the halls of Tbilisi State University had been an unattainable dream. I touched history with my own hand; the past took on flesh.

I am often asked—will the Iviron Monastery be returned to Georgia? According to Church legislation, the Iviron Monastery is not under the jurisdiction of the Georgian Church. Geographically it is located on the territory of the Republic of Greece and has the status of an autonomous monastic community. What does this mean in general, will we get it back? Who took it away from us? Over time, the Georgians abandoned the monastery, and during the Byzantine Empire, the monastery passed to other ‘fellow believers’. Then there was the conquest of the Georgian kingdoms by Russia and the cancellation of the autocephaly of the Georgian Church, Bolshevism and Soviet occupation. We could not maintain the Georgian monastery, the ‘fellow believers’ of the Russian Empire did not want to, while other ‘fellow believers’ could not. Georgian monks were on Mount Athos even in the twentieth century. The Georgian traces on the Holy Mountain have never disappeared from the walls of the Iviron Monastery, and other monasteries as well. From the dining room frescoes, Ekvtime, the great clergyman and philologist of Athos, looks down upon us.

We will ‘bring back’ the monastery when a group of people with the education, morals, and thinking of Ioane, Ekvtime, Giorgi Mtatsmindeli, and Tornike Eristavi work there; when the Georgian state has the political will and economic capacity to take care of historical and cultural centres outside the country; when Georgia returns to European Christian values, which are not measured by church attendance and hypocritical beliefs; when we realise that the word ‘coreligionist’ is an artificial term created by the Muscovite Empire to insidiously deceive Georgians, which the Empire has successfully used for two centuries to confuse us and as a weapon of soft power in hybrid warfare and which we find no analogue in other languages and peoples of other faiths; when we realise the importance and contribution of Athos to the existence of the freedom, statehood, and independent Georgia; when we return to the heart of Europe; when we internalise the values, history, and politics of Europe; when we understand that we are creators and part of these values and history.