Author : Gia Jokhadze

The Soviet Union was a unique empire, with the dictatorship of the proletariat, total terror, the promise of a communist paradise... an empire that ruthlessly established its own clichés and so ruled the conquered peoples. They subjugated cultured Georgia with a cultural model. This justified the approach of the chief ruler Vorontsov: Not hard imperialism, but appeasement and recruitment, when imperial goals and objectives are achieved not by threats, intimidation, and violence, but by seduction, charm, and persuasion. At this time, they did not use the levers of coercion and influence, they offered you co-operation, they slowly pulled the reins of mass consciousness and gently pedalled the human value system.

However common it may seem, it all served a pragmatic purpose: To present Georgians as hero-conquerors of the highlanders of the Caucasus. Here is a possible reconstruction of the seductive phrase: ‘We Russians are a cultural nation, we consider you Georgians a cultural nation, let us together take on cultural oppression and turn uncultured savages into people!’...and together with severed heads and settlements turned into ashes general epaulettes, medals, and favours were distributed. General-poets got used to double standards: Their poetry was a longing for the Georgian kingdom and historical past, and their prose was dogged devotion to the Russian Empire! Who remembered (‘Let bygones be bygones’) that only yesterday their people and country had been turned into coveted prey by the same Russian culture triggers?

One of the seductive clichés that helped the Soviet empire win was the myth of the unbreakable friendship of Russian-Georgian cultural figures. Even then, they proclaimed the culture of ‘one faith’ as a symbol of common identity. For others (say, for the conversion of Central Asians) other models were used. To deceive themselves, i.e. to create the illusion that it was Constanza, they also put the pre-revolutionary past at their service: It is always better to use as an archetypal benchmark an authority who was killed—say, some Pushkin or Lermontov. The third murdered man, Griboyedov, was even married to a Georgian woman! None of them ever wrote (to tell the truth, they had no obligation whatsoever) that they loved Georgia and Georgian culture in general. They observed pictures of nature, got self-excited, remembered their Russian sweethearts, got jealous, and, to explain it, tried to transmute Georgian legends... And the myth (more at home than abroad) spread and took root, because nothing strengthens it as much as an unheard-of lie.

Who remembered that the Russian prisoners of ‘Warm Siberia’ sometimes attacked the Caucasus? If anything, it is an insult to psychology to expect a displaced person to love this place, much less demand it!

And along with unfulfilled hopes and false dreams, which usually become a refuge for the doomed, articles were written about the unbreakable friendship between Russian and Georgian cultural figures, academic degrees were awarded in advance, positions were offered as gifts, invitations to congresses and conferences were sent by post, and offers were made for publication in Russian.

Among the figures of this cliché, Russian poets Konstantin Balmont and Boris Pasternak were relatively sincere: They justified their emotions with deeds (one translated ‘The Knight in the Panther’s Skin’, the other translated almost all Georgian poetry). The Akhmadulina-Yevtushenko duo continued on their path. Akhmadulina even turned ‘Sakartvelo’, ‘Ia (violet)’, and ‘Kvevri’ into elements of Russian prosody. There were others. Perhaps there are still some now...

And together with latent mutual boredom and mental incompatibility grew the number of Russian and Georgian poetic volumes, Russisms without a soft sign and guttural and nasal Georgianisms, long and christomatic toasts and short and accidental sexual adventures...

* * *

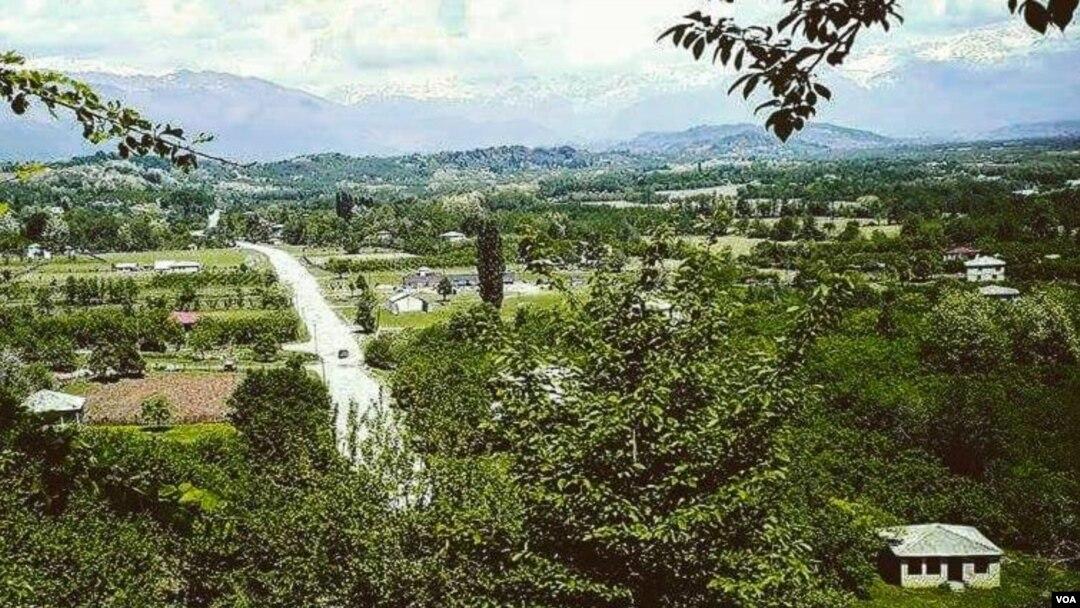

The great Russian poet, Osip Mandelstam, came to Georgia when he himself was not yet, and his country was no longer great. This epithet, ‘great’, was then soaked in great blood and was smeared with hunger, death, and uncertainty about the future. Like his great ancestors, Mandelstam was not attracted to the great Georgian culture. His forced pilgrimage was conditioned by politics, economy, and some other ‘-isms’.

1920. Poets living in independent Georgia received Mandelstam and others in the best possible way. Upon his return, Mandelstam published a letter in the Bolshevik press in which ‘“the Independent” (inverted commas belong to Mandelstam) criticised Georgia’s political and cultural strategy and declared its physically surviving poets from the Blue Horns movement to be incompetent epigones of French Symbolism.’ The prologue softens the aggressive and pro-Bolshevik pathos of the letter: There is a Georgian tradition in Russian poetry that when speaking of Georgia, the voice of Russian poets of the last century acquires a special feminine softness, and the poem itself seems to be immersed in a soft, moist atmosphere. In all Georgian poetry, there are perhaps no two stanzas so drunken and impregnated with Georgian flavour as Lermontov’s. There is a Georgian myth in Russian poetry, which was first expressed by Pushkin, and then Lermontov turned it into a whole mythology. Tamar is at the centre of this myth. Georgia charmed Russian poets with its special eroticism, the admiration peculiar to the national character, the innocent spirit of light intoxication, a kind of melancholic and solemn drunkenness in which both the soul and history of this nation are embedded.

The Georgian Eros is what attracted Russian poets. Russian culture never imposed its values on Georgia. Russification of this country never went beyond the forms of administration. There is no need to talk about the cultural Russification of Georgia. Therefore, the national and political self-determination of Georgia, which is clearly divided into two periods—before and after Sovietization —should become a test of the Georgians’ loyalty to themselves. Cultural Russia, which has watched Georgia with love for a whole century, now looks with concern at a country that is ready to betray its cultural vocation.

Almost every other statement made in this letter is stunningly false—shamelessly false—and poetically irresponsible. But considering that the coloniser usually writes not about living people and countries but about stereotypes he has created and uses his own sources as evidence, our hearts will be less likely to break. A stereotype is destined to be a stereotype—that’s the whole anatomy of this letter.

The author writes with the hand of the empire, on behalf of the empire and for the empire, and this audience is divided into two parts: political leaders and intellectuals. The first ones are advised in the letter to worry less and get to work, while the intellectuals are told not to think much, and improperly chosen quotations are a landmine, and this is what literature is responsible for.

Of course, these are all insinuations, but this is the ABC of postcolonial theory (E. Said et al.).

Now, about mines, the explosion of which indicates the skill of the creator no less than the reader’s discernment:

There is no Georgian creative tradition in Russian poetry, neither of the nineteenth nor of the twentieth century. And in Pushkin’s poem, which Mandelstam quotes inaccurately, it is not about Georgia, but about a satrap who remained in Russia (probably Natalia Goncharova*), Mandelstam-Pushkin’s ‘Georgia’ is only an entourage: Hills with a frowning night and a roaring stream. This, as it turns out, is what gives the voice of Russian poets a special feminine softness and what immerses the poem in a soft, humid atmosphere!

Mandelstam also incompletely quotes two of Lermontov’s lines, drunk in a Georgian way and imbued with Georgian flavour. In the poem ‘The Dispute’, the mountains—Kazbegi and Elbrus—argue with each other. Elbrus warns Kazbegi that if you submit to people, they will soon gut your impenetrable body, extract bronze and gold from your bosom, in short, beware of the East. The Orient will never harm me: Wine is spilling on the pants of a tipsy Georgian, ‘drugged with opium on his divan slumbers Teheran, Jerusalem is lying at his feet o’erthrown, and beyond the yellow Nile washes the royal tombs, In his tent, the hunt forgotten— Now the Bedouin lies, sings the old ancestral legends, scans the starry skies.’ In short, ‘the Orient can harm me not’, boasts Kazbegi. Don’t brag in advance, look to the north, says the ‘all-knowing’ Elbrus. The Russian army is approaching from the north. When Kazbegi, black with anger, cannot count the number of those approaching, he hides his head in the clouds, as if putting on a hat, and goes silent forever. So, the imperial stereotype of Georgia is a tipsy Georgian who spills his pride—his dignity—on his Oriental pants. Let him sleep before the Russian army wakes him up!

In connection with Mandelstam’s Georgian Eros, I recall the scheme of the poem ‘The Marriage of Georgia to the Russian Kingdom’ by the 19th-century Russian Decembrist poet Alexander Odoevsky (1802-1839), who was sent as a private to ‘warm Siberia’ (the Caucasus) in 1837 and was close to Lermontov: Georgia is a black-eyed maiden, a passionate daughter of dawn and fire. Many desire her, but she prefers a fair-haired, iron-armed giant, the ruler of the axis of the world. Near Kazbegi, in the Daryali Valley, near the foam-covered Tergi, the maiden embraces the broad chest of her beloved: ‘Quiet the pain of the past, inflame yourself with eternal love for Russia, merge with it like battle steel, purple like the dawn,’ says the poet, saying goodbye to metaphors and, as they say, calling everything by its name.

As we can see, since the nineteenth century there has been no Georgian tradition in Russian poetry, it is the tradition of Russian-Georgian flirtation or marriage with poetic-political sexuality, when Georgia is a woman, a wife, or a lover.

Mandelstam’s placement of Tamar at the centre of Lermontov’s Georgian mythology is in fact a desecration of Tamar, whom the Georgians consider a national sanctuary. Lermontov was told several legends about a beautiful woman characterised by a certain passion and cruelty: It was as if she lorded over the Darial. A huge toll was charged from every passerby; a man whom she liked, she detained to share the bed with her and those lovers whom she was dissatisfied with, she had killed and thrown into the Tergi. Georgian folklore has indeed preserved variants of such plots. The woman was sometimes referred to without a name, sometimes as Daria and sometimes as Tamar. Lermontov chose Tamar (this is the name of the protagonist of both his poem ‘Demon’ and his ballad (‘Tamar’). Mandelstam placed this Tamar at the centre of Lermontov’s Georgian mythology.

1921. Mandelstam, the author of the aforementioned letter, again came to Georgia, this time with his newly married wife. ‘Titsian Tabidze “blames” Paolo Iashvili: ‘His heart was touched by his tears, and his wife’s presence also affected him, so I forgave him.’ They hosted him again, accommodating him once more. And at the same time, they found a mercantile, ‘legal’, and decent way of living for him: In exchange for a fee, they commissioned the translation of some of Vazha’s works and poems of the ‘Blue Horners’. But Mandelstam soon reverted to his old self: That ungrateful and arrogant creature to whom all graces belong simply because he is who he is, not someone else. Mandelstam had no intention of repenting for what he had done (such a feeling was completely alien to him). The Blue Horns members said they forgave him. ‘Forgive me... what had I done to be forgiven by you?’ The inhospitable, and therefore, harsh, and hungry life began, which was especially felt in Georgia. He felt it too. The couple had to save money to return to Russia, and as soon as they could, they left.

A new letter by Mandelstam appeared in the Russian press: This time, he again recalled Menshevik Georgia, ironically and arrogantly, seeking to align with the prevailing circumstances. ‘...the small “independent” state, having grown at the expense of others’ blood, wished to remain bloodless. Harassed by hostile forces, it aspired to enter history untainted and peacefully, as if it were a new Switzerland—a territory neutral and “immaculate” from birth.’

One gets the impression that Mandelstam is attempting to convince some collective Bukharin that Georgia is an anti-Soviet creation, as if neither the revolution nor the First World War had occurred, implying a disregard for their consequences.

Household Mandelstamism: He took with him either a fur coat or a winter coat of Titsian Tabidze (this was also the ‘fault’ of Paolo Iashvili’s kindness!), a warm coat in Tbilisi, well, what a need!

1923. Titsian Tabidze responded to Mandelstam’s second letter—At home, in the literary annals, but with fury and political ruthlessness, explicitly criticizing him for defaming his homeland and implicitly condemning all his derogatory remarks. The expression ‘Jewish brat’, which was likely interpreted as ‘snake’, was singled out from the context of ‘anti-Semitism’ and associated with someone who frequently changes their place of residence or work to get by.

The letter, titled ‘Touring Brat’, was published in the newspaper The Rubikon, a revelatory and harsh letter, but Georgians soon forgot about it, and Mandelstam heard nothing more of it until the 1930s. Georgian writers probably no longer wanted to further humiliate the rejected, finally exiled, and oppressed Mandelstam:

Nor would protecting Menshevik Georgia have been a safe endeavour! In short, they forgot—not just the incident itself, but the letter as well. It remained, yet no one laid eyes on it, or perhaps the opposite was true. Once upon a time, three researchers (one Georgian, two Russian) recalled this incident with euphemistic shyness, but they chose not to shatter the cliché: That Georgian and Russian culturalists remained friends—henceforth and forever, or so it seemed, at least until 1930. It was then that the Mandelstams arrived for the third time in Georgia. However, none of his colleagues welcomed the poet’s presence there. Mandelstam had already resolved to craft a new myth—‘Journey to Armenia’.

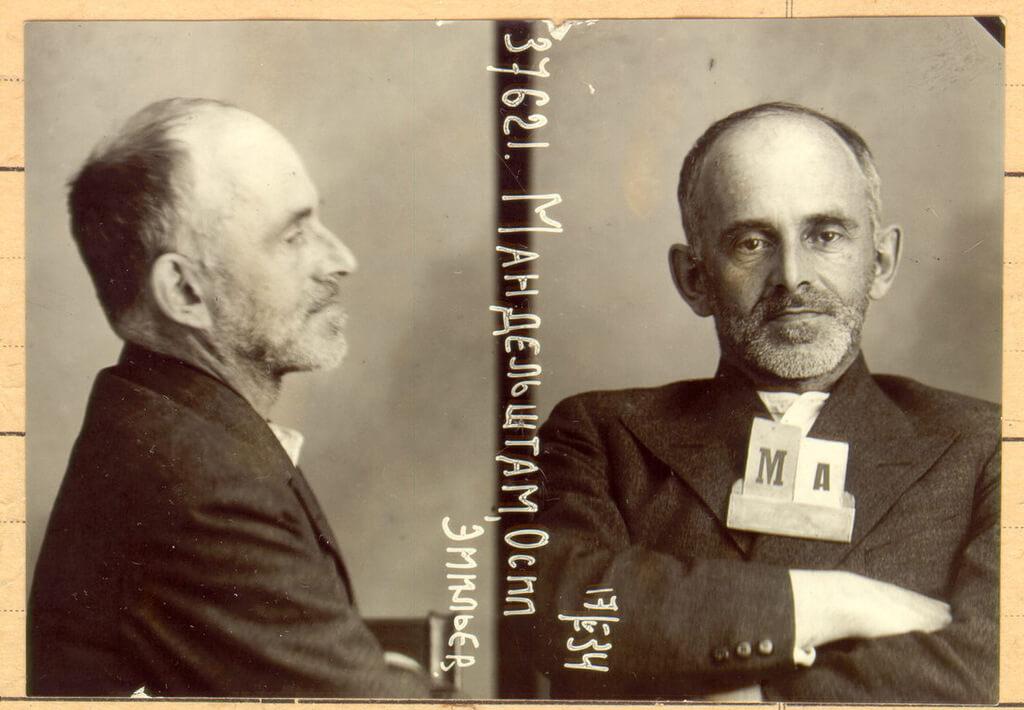

In November 1933, Mandelstam wrote a fateful untitled poem, first called ‘Epigram’ and then ‘Anti-Stalinist Epigram’. But even more fatal was the fact that the poet himself read the poem to his friends and acquaintances and warned them not to utter a word of it anywhere. Pasternak compared the writing of ‘Epigram’ to suicide: ‘You haven’t read anything, I haven’t heard anything, and please don’t let anyone else read it,’ he scolded Mandelstam, who was waiting for an evaluation. Nadezhda Mandelstam would have liked to establish her assessment of ‘Epigram’: ‘This poem was an act, a heroic act that logically derived from Mandelstam’s life and work.’

Someone, having heard this poem, denounced Mandelstam. In May 1934, the poet was arrested, sentenced to exile in the Urals for three years for anti-Soviet agitation, and then the sentence was replaced by ‘imprisonment’ in Voronezh. In May 1938, Mandelstam was arrested again on charges of anti-Soviet agitation, and this time he spent 5 years in a labour camp in the Far East. On December 27th, the exiled poet died of typhus.

As early as 1930, in another condemnation of his literary enemies, Mandelstam went as far as forbidding them from having children, hinting that three generations prior, they had made a pact with the devil, marked by smallpox scars (most commentators interpreted this as an allusion to Stalin, who had survived smallpox). Obviously, Mandelstam had no intention of printing this text, and referred to as ‘the fourth prose’. On the contrary, he carefully concealed it.

Four years passed. Mandelstam witnessed the agony of Ukraine, destroyed as a result of collectivization. It’s difficult to determine what creative delirium seized him, but whatever was born, was born.

‘We are living, but can’t feel the land where we stay,

More than ten steps away you can’t hear what we say.

But if people would talk on occasion,

They should mention the Kremlin Caucasian.

His thick fingers are bulky and fat like live-baits,

And his accurate words are as heavy as weights.

Cucaracha’s moustaches are screaming,

And his boot-tops are shining and gleaming.

But around him a crowd of thin-necked henchmen,

And he plays with the services of these half-men.

Some are whistling, some meowing, some sniffing,

He’s alone booming, poking, and whiffing.

He is forging his rules and decrees like horseshoes—

Into groins, into foreheads, in eyes, and eyebrows.

Every killing for him is delight,

And the Ossetian chest is wide.’

This suicidally defiant invective has an Achilles’ heel—the last line, which still elicits rebukes similar to those of the poem’s first listeners. ‘How could he write this poem—he’s a Jew!’ Pasternak was resentful. The hero of the contemporary Russian writer Leonid Zorin’s novel, Jupiter, an actor, was so inspired by the role of Stalin that he even kept a diary on his behalf, which contains this stream of consciousness: ‘Where did that last line come from? “The broad chest of an Ossetian”. What a disaster. He couldn’t find a rhyme? First, he discusses the death penalty, reaching a high note, so to speak. Then suddenly, like a tailor taking measurements, he recalls the broad chest. The death penalty—then swiftly transitioning to thoughts of a sweet life and the chest, particularly the chest of an Ossetian. It’s not the first time I’ve heard about my Ossetian ancestry. Some people even claimed I was a bastard. When I was young, it infuriated me; who knows what I might have done. Over time, I’ve grown more resilient. Those rumours no longer sting. However, it’s not a poet’s business to repeat and rhyme them in verse.’

Modern Russian and American philologists (Lada Panova and Alexander Zholkovsky) have drawn attention to the ideological ‘falseness’ or ‘political incorrectness’ of the last line:

‘It’s a sort of racist outburst. The meaning is approximately as follows: our Kremlin, and further on, our Russian language, have been seized and desecrated by barbarians, Tatars, and some “Chuchmeks”. By the way, Brodsky uses this nickname for non-Russians in his play “Democracy”: the great empire is collapsing and changing its face. A stereotypical Georgian has been appointed its Minister of Foreign Affairs: Chuchmekashvili!’

Some interpreters considered the line ‘broad chest of an Ossetian’ superfluous, false, ineffective, as it distorts the powerful ‘ode’ with one word (literally—one word). In the opinion of some, this word was ‘hanging in the air’ and was ‘perceived as biographical information, unnecessary specificity of the “Kremlin’s highlander”’: ‘Or what is so terrible about the word “Ossetian”?’ It was said that Mandelstam was going to drop this line... Did he not have time, or did he not want to?

Others prefer the more literary ‘Ossetian chest’ over the less refined but more expressive ‘Georgian’ version. The story in question is recounted by the Soviet and American literary historian Sofia Bernstein-Bogatyreva. According to the author, the only text that Nadezhda Mandelstam did not entrust to paper when copying or reprinting her husband’s so-called archive—various disparate poems—was ‘Epigram’. However, she granted Sophia the right to memorize it, along with not only the known version but also its variations. ‘I have always cherished this poem in my heart, but in a version that lacked the offensive word.’

What is meant here? Something that Sofia’s father—a writer and literary man, Ignatius Bernstein, would recite sometimes:

«Что ни казнь у него—то малина

И широкая жопа грузина».

(‘Every killing for him is delight,

And the Georgian arse is wide.’)

The ‘street word’ uttered by Sofia’s father in a house where strict rules reigned, and in the presence of a child, created such an unusual situation that the girl immediately memorised it. The father even shrugged his shoulders, ‘Georgians are narrow-hipped’.

As we can see, in this version, instead of ‘Ossetian’s broad chest’, ‘Georgian’s broad arse’ is mentioned!

Many Mandelstam scholars have attempted to elucidate the significance of the ‘Ossetian’ motif in the poem. Contemporary Russian researcher Yuri Borev, known for collecting rumours and anecdotes about the ‘father of the people’, suggests: ‘The line in Mandelstam’s poem, ‘And the broad breast of an Ossetian...’, hints at the existence of unofficial information about Stalin’s nationality in the 1930s. However, these reports are conflicting: Some claimed that Dzhugashvili was an Ossetian surname, while others mentioned Egnatashvili. According to a third account, Stalin’s mother was of half-Ossetian descent.

The American linguist Boris Unbegaun highlighted that the surname ‘Jughashvili’ originates from the Ossetian word ‘jukha’, which translates as ‘garbage’ or ‘waste’. I would like to add that the word ‘Jughi’ (and not ‘Jugha’!) remains unexplained in Sulkhan-Saba’s dictionary; the lexicographer only references a passage from the old Georgian translation of Isu Zirak’s biblical book. Additionally, the character in Grigol Robakidze’s novel Killed Soul suggests that ‘Jugha’ may be an old Georgian term, meaning ‘iron cinder’, referred to as slags by other peoples. In the notes to the poem, modern Russian researcher Alexander Metz provides intriguing information, suggesting that the surname ‘Dzhugashvili’ literally means ‘son of an Ossetian’. Vladimir Mikushevich and Andrei Voznesensky perceive the word ‘Ossetian’ as a concealed signature of Mandelstam—‘Osip’.

But why did Mandelstam need an Ossetian motif for this passionate invective? Professor at Princeton University, Slavist Ilya Vinitsky, tries to explain this. According to him, in Russian ethnographic iconography of the 19th and 20th centuries, Ossetians were indeed depicted as broad-chested. Vinitsky quotes a fragment from the dissertation dating back to 1890: ‘Ossetians for a whole century have belonged to the highland people, i.e. they live in conditions that especially prepare the chest for vigorous respiratory excursions; as a result of this the circumference of the chest gradually increases.’

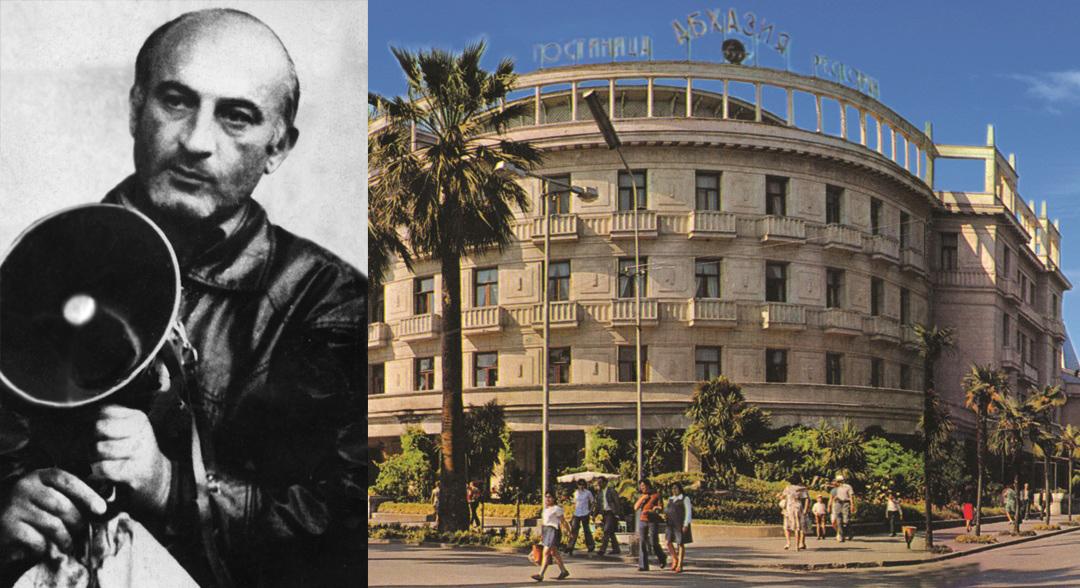

Meanwhile, Stalin, as we know, was not a man of large, athletic build. According to the researcher, Mandelstam’s associations with the ‘Ossetian theme’ stem from a common source: Mikheil Javakhishvili’s novel Jaqo’s Dispossessed, published in 1924-25. The researcher highlights that in 1924, authorities suppressed an anti-Soviet uprising. I would like to add that in 1929, the novel was first printed in Russian, initially in Tbilisi and then in Moscow. Indeed, the text contains markers whose echoes resonate in Mandelstam’s ‘Epigram’:

The brutal and opportunistic Jaqo Jivashvili and his relatives came down from the mountains—they are highlanders; Jaqo has a ‘face and hands constantly smeared with oil’, is ‘from head to toe greased’, with ‘thick fingers’, a ‘fatty paw’, ‘sweaty finger’, and a ‘broad chest… pushed up like a pillow’ or ‘chest like a pillow’, and so on.

Vinitsky recalls one passage of the novel Killed Soul as Grigol Robakidze’s Ossetian theory to explain Stalin’s biological mystery. Here’s what he means: ‘Lenin gave Stalin the unusual nickname “legendary Georgian”. Legendary traits abound in Stalin, but his Georgian identity is minimal. In Georgia, Stalin’s unique character is attributed to his ancestry: His father was Ossetian by birth. However, it’s possible that we’re dealing with another phenomenon. Deep within every nation, there arises a seed foreign to it, or even opposed to it. This appears to be a purely biological mystery. Perhaps the nation’s ability to birth something alien to itself is destined to supersede foreign nationality? Stalin is Georgian only to the extent that he embodies its antithesis.’

In 1978, rights defender and writer Faina Baazova published her memoir, Tanks Face-to-Face with Children in Israel, where she reflected on Georgian public opinion during the 1920s-30s:

‘Long after the suppression of the 1924 uprising, both among the people and the intelligentsia, the name “Soso Dzhugashvili” was uttered with contempt. This sentiment may have contributed to the popularity of one of the characters in writer Mikheil Javakhishvili’s novel—the Ossetian Jaqo—a crude, cunning, and ignorant opportunist and rapist, with whom many people found similarities to Stalin.’

Let us remember what Mikhail Javakhishvili said about one of the inspirers of the face of Jaqo:

‘Thirty years ago, I met a strange stranger in the Djava Gorge. He was large, hairy, cunning, greedy and at the same time agile and dexterous. I have forgotten his name. Ten years later, engineer Fido Kazbegi told us in a Georgian club such an anecdote: “A former serf brought his princess an offering: —Hello, Jaqo! —My humble bow to the princess! —What are you doing, how are you? —I live very well! —How is your family? —They’re all well! —How many children do you have, Jaqo? —Twelve, light of my eyes! —How did you manage to produce so many, Jaqo? —That’s it! That’s what Jaqo can do! replied the former serf. The last three words were even more strongly peppered. Generally, an anecdote is never kept in my memory for more than five minutes, but this obscenity somehow merged with the appearance of that Djava man, and the image was thoroughly lodged in one of the corners of my memory. About ten more years passed, and quite unexpectedly the image came to life, exposed before me. That’s how strangely a character is sometimes born.’

They also claimed that the so-called Ossetian myth was propagated by Trotsky.

It should be noted that his book on Stalin was written in 1938-40, i.e. much later than ‘Epigram’ was written. In 1935, Boris Souvarine, a French writer and political activist of Jewish origin and an anti-Stalinist Communist, published his seminal work Stalin: An Outline of the History of Bolshevism, although the author had begun work on the book in 1930.

A year before ‘Epigram’ was written, in 1932, the Georgian Menshevik Iosif Iremashvili, who had fled to Berlin and was a colleague of Stalin’s at both the Gori Theological School and the Tbilisi Theological Seminary, published a book in German entitled Stalin and the Georgian Tragedy. However, we learn all this from Trotsky’s book: ‘Georgian emigrants living in Paris assured Souvarine, the author of the French biography of Stalin, that Ioseb Dzhugashvili’s mother was not Georgian, but Ossetian, with Mongolian blood mingled in her veins. In contrast,’ Trotsky added, ‘a certain Iremashvili claims that his mother was a pure-blooded Georgian, and his father was an Ossetian, “a rough, uncouth figure, like all Ossetians living in the high Caucasus mountains.”’

Here is a translation of a passage by Iremashvili: ‘Beso-Besarion... was an ethnic Ossetian. On his head he wore a Russian hat and, like all Ossetians living in the Caucasus, had a heavy, inflexible character.’

Trotsky used Stalin’s Ossetian origin to explain the character of his main enemy: ‘Ossetians are known for their vindictiveness. They retained, at least during Stalin’s youth, the custom of blood feud from clan to clan. Stalin transferred this custom to the realms of high politics.’

Even earlier, Grigory Zinoviev had called Stalin ‘a bloody Ossetian who does not know what a conscience is’.

In the first half of the 1930s, the Ossetian motif reached the secret anti-Soviet poetry, in which the Stalin theme had already taken hold. Here is one example:

«А кто ж ведет страну к провалу,

Кто налагает карантин,

Детей толкает в пасть к Ваалу?

Почтенный Сталин—осетин…»

(‘And who is leading the country to failure,

Who imposes the quarantine,

Who pushes children into the mouth of Baal?

Honourable Stalin—an Ossetian...’)

It is still unknown what prompted the poet to write the ‘Anti-Stalin Epigram’ and, in particular, the last line. In general, Mandelstam, who did not take too kindly to non-Russians, wanted to point out the savagery and uncivilised nature of Stalin. The general pathos of the text and the presentation of him as a ‘highlander’ and a ‘broad-chested Ossetian’ should have served this purpose. The choice of an epigram as a form, that is, a satirical work intended to ridicule someone or something, provided more opportunities for this. Mandelstam’s intention is difficult to determine, but it should be clear that Stalin’s cruelty and treachery were largely to blame for his non-Russianness—his Caucasian origin, upbringing, or customs (and here it is not so important whether Stalin is declared an Ossetian or a Georgian). Certainly, as a poet, Mandelstam had the right to express himself, but as a human being, he displayed his typical biases. More broadly, this case highlights the stark separation between the methods, tools, and objectives of culture and politics: When culture attempts to subject politics to catharsis, it turns to state terror. This represents a universal constant: Mandelstam acted as a poet ought to act, yet the state treated him in the manner it treats poets—he was expelled.

However, in 1937 Mandelstam, locked in Voronezh and hearing the breath of death, wrote an ode to Stalin—mysterious, unusual, and mystical—but still an ode!

‘Into the distance stretch the mounds of people’s heads:

I become small up there, where no one will espy me;

But in kind-hearted books and children’s games, instead,

I’ll rise again to say the sun is shining.

The warrior’s frankness: There exists no truer truth.

For air and steel, for love and honour,

One glorious name takes shape on reader’s tongue and tooth,

And we have caught it and have heard its thunder.’

No one knows whether Stalin read this text or not. A year later, Mandelstam was exiled to Vladivostok... forever.

* * *

John Maxwell Coetzee dedicated an article to Mandelstam’s ‘Ode to Stalin’, in which he noted: ‘In the chess game of power that Stalin played not only with Mandelstam but with all those masters of the word to whom it would fall to pronounce the last word on him and his times—a game in which Stalin cannily sought to pre-empt their verdict by demanding their best last words there and then—we may think of Mandelstam, in his own ode, as playing for a draw. Not an equal draw (that would be too much of a provocation), not even a draw too actively played for: Rather, one of those technical draws that a weaker player can sometimes slip into without seeming to slip it over his opponent, emerging with a lucky half-point, outgunned but not disgraced.’

The final years of Mandelstam’s life were marked by a tacit strategy for avoiding disgrace, as well as serving as a vivid illustration of how the archetype of the martyr emerges from the soul of the empire—through irrational stubbornness, religious fortitude, and poetic madness.