Author : Zaza Bibilashvili

Congratulations! Georgia is a candidate country for EU membership!

As I write this, I realize that congratulations seem to belittle this great event, because it is not just a fact to be congratulated on. It is an epochal, tectonic shift in our living history.

So many generations have been born and died in a Georgia conquered by empires. A Georgia that hardly anyone outside its region knew about.

So many generations have dreamed that the world would simply become aware of the existence of Georgia, and that those who knew about it would not regard this ‘fairytale country‘—as the great Knut Hamsun called Iberia—merely as an exotic province of Russia. How can you achieve real success when even your dream is so modest? When your ambition is only to have your existence recognized!

In this context, the idea of the West accepting Georgia as part of Europe was beyond our wildest dreams. That is why we adopted the term ‘Caucasian‘ to define our identity, to distinguish ourselves from the regions of the Middle East and Central Asia, which felt completely alien to us. How could we have imagined being considered European when, only 85 years ago, even Czechoslovakia, in the heart of Europe, was to an Englishman ‘a distant country about which we know nothing‘ (and therefore ceding it to Hitler was no problem).

But the evil greed of another Russian tsar and the heroism of our fellow Ukrainians turned everything upside down and made our dream come true.

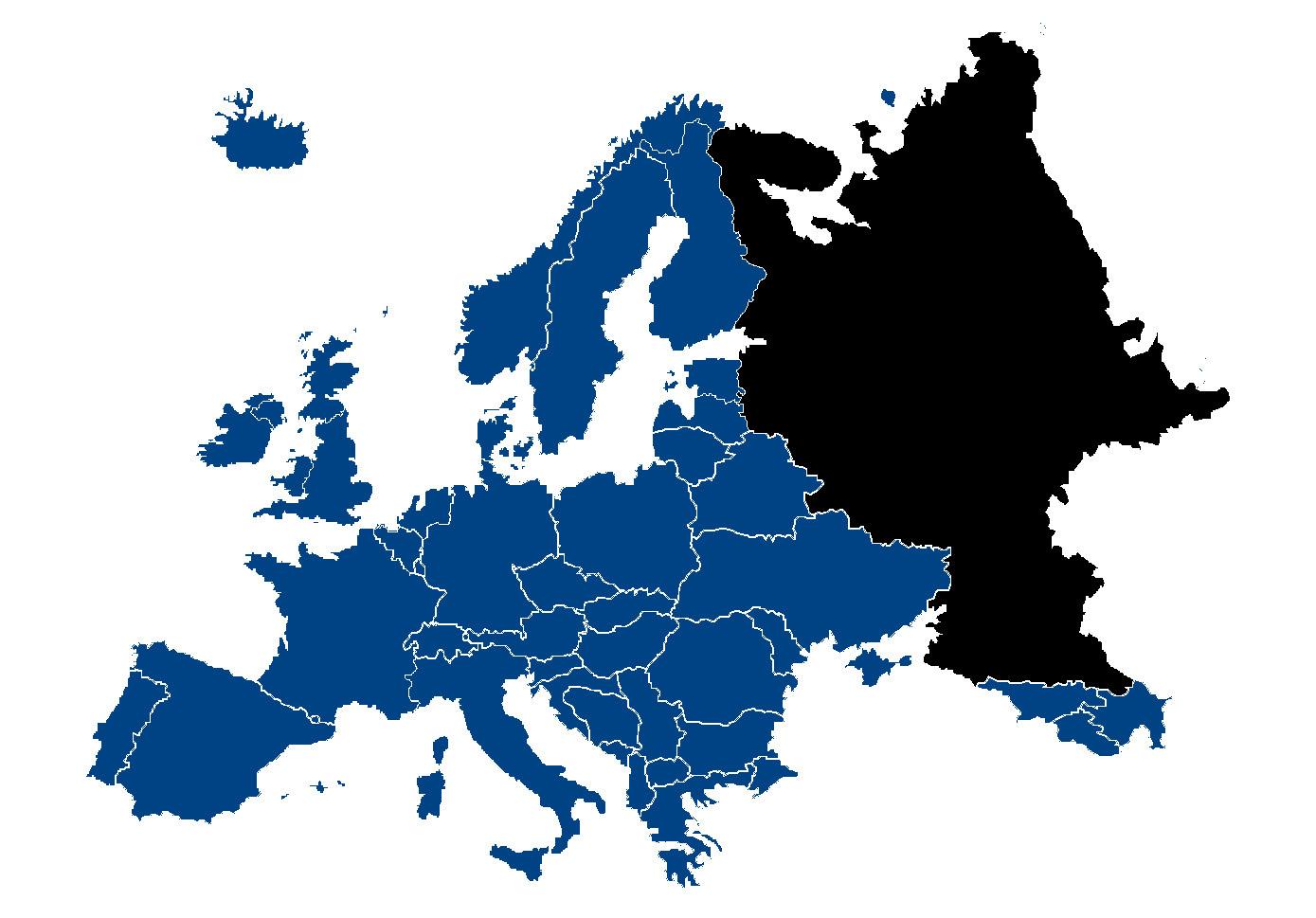

That momentous day came on December 14th, 2023, when Europe officially declared that its borders would now extend from Lisbon to Tbilisi.

The Ivanishvili government has spared no effort to prevent this from happening. What haven’t we witnessed in these two years?

• Allegations that bringing up the Candidate Status issue was a deliberate provocation aimed at ousting Dream from power;

• Unceasingly berating Georgia’s European allies in an undignified manner, coupled with an even more undignified content;

• Endless flow of anti-Western propaganda, directly tied to government strat-com;

• Promulgation of conspiracy theories at the highest official level;

• Establishment of aggressive groups intended to attack journalists and minorities;

• A treacherous and, fortunately, unsuccessful attempt to introduce Russian law;

• The resumption of direct flights with Russia against the advice of the West;

• Demonstrative alignment with figures like Orban and authoritarian China.

Indeed, Dream intentionally orchestrated these actions to sabotage the status.

However, there was one notable exception—a conspicuous absence of an outright rejection of Georgia’s European future. This omission appears to be solely driven by self-preservation. Let us not forget the repercussions faced by Viktor Yanukovych when he ventured down a similar path in a country far less pro-European than Georgia.

And when Dream could no longer resist the inexorable tide of history, the determined will of the Georgian people and an awakened Europe, it decided to lead the jubilant population like Kvarkvare, pretending that it was its celebration as well.

However, to understand the true mood of the country’s leadership towards European integration, it is necessary to listen to the voices of the so-called People’s Power—a blatant and frighteningly dark faction that has been singled out as a separate brand in the official Dream Syndicate.

And if we listen carefully, it is clear that the Dream has much darker plans for the near future.

Therefore, no matter how epochal Candidate Status may be, it is by and large only a recognition of our existence, of our Europeanness. We have a long way to go before we become Europe. Gaining the status was merely the first step. Unless there is a profound change in the country, this step will remain just that, a step: We will still have a sanctioned court, a state machine that shields high-ranking Russian agents, and a clan-based oligarchic government, under which deep and comprehensive corruption has become the norm again, almost as it was before the Rose Revolution.

‘Almost‘ because thanks to the previous government, we moved from the lower levels of Maslow’s pyramid to the upper levels, and now corruption has a more civilised form (‘cops‘ no longer rob us directly on the roads, pensions are issued on time). ‘Almost‘ because the scale of corruption before the Rose Revolution, compared to today, seems like child’s play....

Life in Georgia in the 1990s was akin to hell on earth. It was a kind of mixture of Somalia and Afghanistan, a failed state, a lawless, uncontrolled territory where the law of the jungle reigned, and the modest goal for a decent person was simply survival. A pension of 14 GEL, which was not given for years, crime, corruption, no light, no gas, no roads, hopelessness, kidnapping for ransom (a business run jointly by banditry and law enforcement agencies)—this was our daily reality.

Then, one beautiful day, this hell came to an end and Georgia began to rise. That day was November 23rd, 2003, when the Rose Revolution gave birth to a new Georgia and whose 20th anniversary was celebrated in November.

By all objective and measurable criteria, the Rose Revolution was followed by one of the most successful periods in Georgia’s documented history—a remarkable nine years of progress.

Later, however, we allowed Russia to retaliate (I won’t go into the details, but I will echo Dugin’s words: ‘If we had entered Tbilisi with tanks in 2008, we could not have installed a better government’). There has been a lot of discussion about this, and no doubt there will be more (if Russian-style ‘sovereign democracy‘ gives us the opportunity). This current issue of the magazine will focus mainly on Abkhazia.

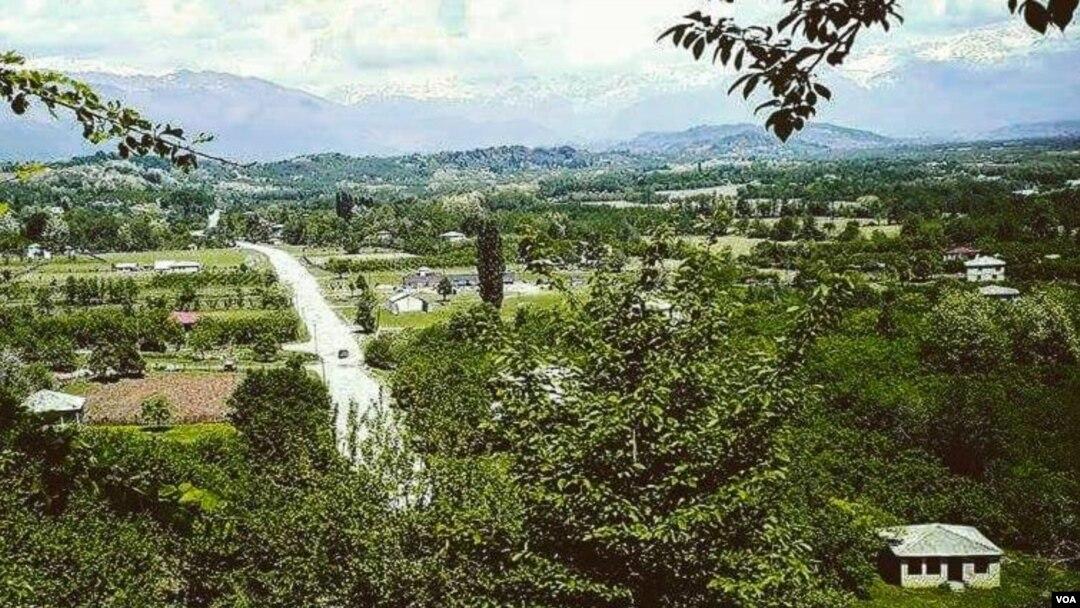

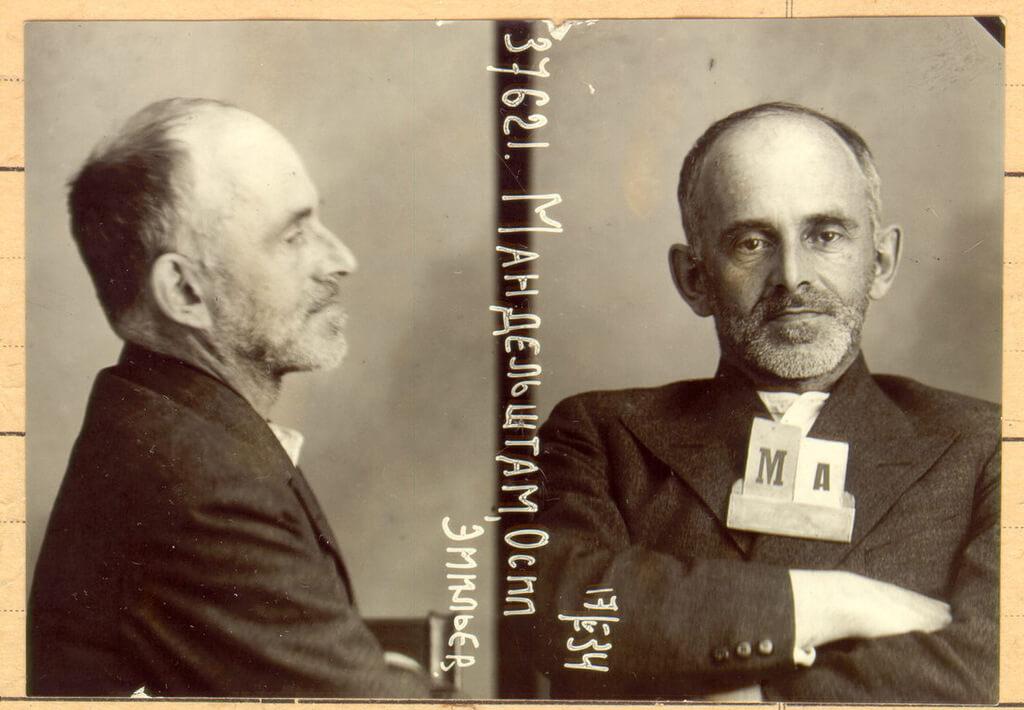

In September 2023 there was another anniversary. This time it was a tragic one. September 27th was the 30th anniversary of the fall of Sukhumi and the temporary occupation of Abkhazia (even here we are lied to when they say that the occupation of Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region began in 2008—that was simply when it was labelled as an occupation).

In this issue you will find memories, thoughts, questions related to Abkhazia... read them, feel them, believe them as your personal memories... and I will offer some theses for your consideration. No one has ever explicitly stated these theses in the context of conflict resolution. Accordingly, we blindly follow ‘planted‘ narratives about Abkhazian brothers whom the Russians made kill us and with whom we should make peace. Brothers who see us as enemies (which we do not realise) and who do not seek reconciliation with us. Nor do they care about the realisation of their own deeds.

Therefore, we have to say:

During the war in Abkhazia, three peace agreements were signed, and all three were used by the Abkhazian side to exterminate Georgians en masse. Yes, the barbaric, internationally recognised ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia (genocide according to some estimates) was planned by the Russians, but the perpetrators were mostly Abkhazians. The hatred that turned ordinary people into cold-blooded killers and made genocide possible was also one-sided. It remains one-sided today.

You will say that Russia ruled on both sides there. To some extent it did. The crime of the Abkhazians is all the more serious because the Georgian side did not kill Abkhazian civilians on ethnic grounds, but the Abkhazians are collectively responsible for organised, planned massacres of civilians on ethnic grounds in Gagra and Sukhumi (from where heavy weapons were withdrawn in connection with the peace agreement).

According to the Russian propaganda version often found in foreign-language sources, the atrocities were committed mainly by those Abkhazians who had experienced something similar themselves. It should be said that this is a lie. In fact, by 1 October 1992, when the Gagra genocide took place, only a few dozen people had died in the war, almost all of them military personnel.

What happened in Abkhazia was far worse than Bucha (if such a thing can exist in nature), because if the Bucha genocide took place during active hostilities, the mass slaughter of peaceful Georgians in Abkhazia under ceasefire conditions was a cold-bloodedly planned and methodically executed act of genocide.

And now the most important matter:

We often hear that if you want the Abkhazians to trust you, you should create a state—with democratic institutions and a free judiciary—in which they would want to live. But no one asks: Perhaps the Abkhazians, who represented 18% of the region’s population before the war, are not afraid of ‘bad‘ democracy, but of democracy as such, a system in which every person has one vote? Perhaps for those who have lived under de facto apartheid for decades, and for whom ethnicity has meant guaranteed privileges, giving up privileges is unacceptable?

We may be told not to bring up old traumas. But old traumas don’t go away. Traumas should be studied, not forgotten. Understanding history is the only way to building a common future. It is not so difficult to walk this path. Today it is blocked by Russian bayonets, which for 30 years have divided Georgia into territories on opposite sides of the Enguri River, preventing the catharsis of the Abkhazians and the return of the displaced to their homes.

And since memory is the key to a victorious peace, let us always remember Sukhumi. And until we return, let us repeat it, calmly and with faith:

Next year in Sukhumi!