Author : Iulon Gagoshidze

Andrei Sakharov once said that Georgia is a small empire. Why he said this is another matter, but he based it on the fact that there are many other ethnic groups living in Georgia besides the Georgians. This is indeed true and has always been so, for several millennia of the existence of the Georgian state, as evidenced by ancient Georgian and non-Georgian written sources.

Georgia has always been a multinational country. An old Georgian chronicle tells us that even in ancient times the rulers of Kartli sheltered and settled near Mtskheti Turks persecuted by the Persians and then the Urians (Jews) expelled from Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar, who over time spoke Georgian and differed from ethnic Georgians only in their religion. The same is true of the Armenians: It is difficult to say whether the Georgian-speaking Armenians living in the villages of Kartli, Kakheti, Racha, and Lechkhumi are Georgianised Armenians or Georgians who have adopted the Armenian-Gregorian (Monophysite) faith (the Armenians living in Javakheti were resettled from Turkey by the Russian authorities in the 19th century; thousands of Armenians arrived in Georgia in 1915-16).

The list of members of the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of Georgia from 1918 to 1921 is noteworthy in terms of ethnicity and religion. This list includes Georgian Orthodox, Georgian Catholics, Georgian Gregorians, Georgian Israelis (Jews) and Georgian Muslims, as well as, in addition to them, Abkhazians, Greeks, Germans, Tatars (Azeris), Ossetians, and Russians.

In Georgia, Armenians and Persians lived side by side with Georgians since ancient times, especially in the cities, while Arabs lived there (in Tbilisi) from the eighth century. Thus, the unified Georgian state, which in the process of its formation included other, not specifically Georgian lands, was from the very beginning a multiethnic formation (state), which was reflected in the titles of the medieval kings of Georgia: ‘The King of the Abkhazians, Kartvels, Rans, Kakhs and Armenians, Shirvan-sha and Shahan-sha‘, in which, of course, Georgians were also mentioned, but not in the first place. The reason for this is that in the 10th century, the initiator of the process of unification of the states in the Caucasus after the Arab campaigns was the King of the Abkhazians, Bagrat III, who became the King of the Georgians after the death of his father, the King of the Kartvels, Gurgen. The process of unification of the country, which lasted more than a century, was completed by Davit IV the Builder in 1122 with the capture of Tbilisi and its proclamation as the capital of the country. Before that, for 33 years, Davit the Builder ruled the country from the capital of the Kingdom of Abkhazia, Kutaisi. For a long time, even before Queen Tamar (1184-1210), the kings of Georgia were referred to for short as Abkhazian kings, and Georgia was Abkhazia for foreigners. Fascinated by the beauty of the noble lady of Tbilisi, the great Persian poet of the 12th century Khakani wrote in a poem dedicated to her: ‘The beauty of the Abkhazian woman made me learn the Georgian language‘.

In the Middle Ages, the rights and duties of a resident of the Kingdom of Georgia were determined only by his social status, not by his ethnic or religious affiliation. Let’s remember that during the reign of Tamar, the brothers, Zakare and Ivane Mkhargrdzeli, Kurds by ethnicity and Monophysites by faith, held the highest official positions. One was Amirspasalar (Commander-in-chief), and the other was Atabag (Ruler of Samtskhe) and Msakhurtukhutsesi (Chancellor).

This tradition continued until the late Middle Ages, when the Loris-Melikishvilis, Korganashvilis, Tumanishvilis, Bebutashvilis, Argutashvilis, followers of the Armenian-Gregorian (Monophysite) faith and/or of Armenian origin were enrolled in the ranks of the Georgian nobility and actively participated in the administration and defence of the country. The Muslim population of Qajar (Azerbaijan) and Borchalo (Marneuli) remembered until recently that their ancestors served in the personal guard of King Erekle.

Tbilisi’s Christian churches of various denominations (Orthodox, Catholic, Monophysite, Protestant), synagogues, Sunni and Shiite mosques and the Zoroastrian Temple of Fire—the Ateshgah—are symbols and documentary evidence of the multi-ethnic and multi-religious character of the citizens of the old Georgian state.

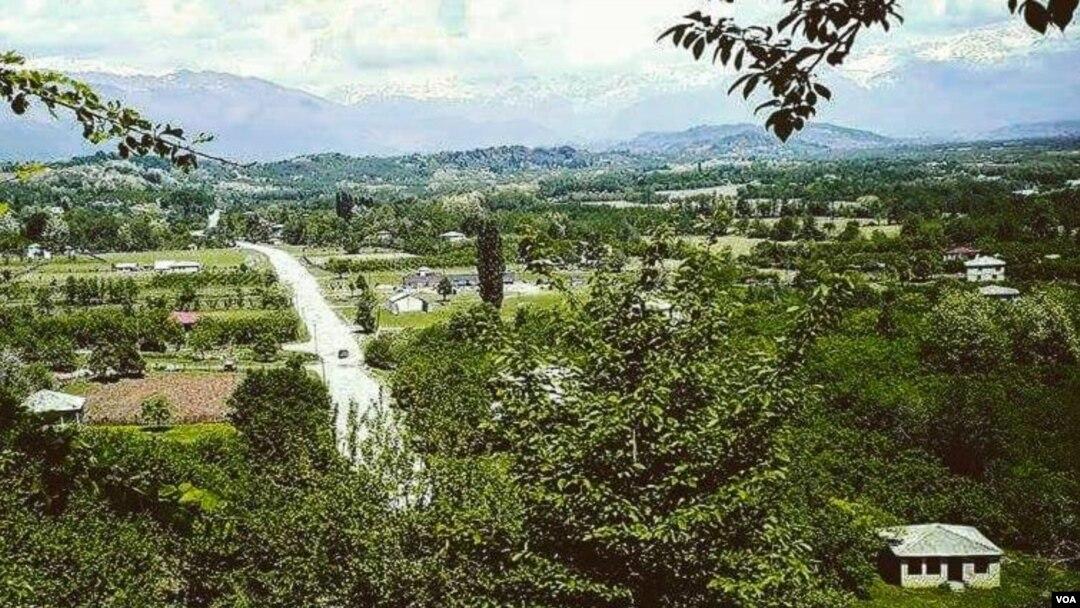

The Abkhazians are the only exception among the non-Georgian citizens of Georgia who have no homeland other than Georgia. An analysis of ancient written sources, which for the first time mention the ancestors of today’s Abkhazians, allows us to say that at the beginning of the Christian era they lived south of the main Caucasian range, on the shores of the Black Sea. Any earlier period can only be judged based on archaeological data. It is archaeology that shows that in the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age there is no trace of any movement of ethnic groups from north to south (unless we count the Iranian-speaking Cimmerians and Scythians, who from time-to-time organised raiding expeditions across the Caucasus to the Middle East, but usually returned to their native Eurasia). Therefore, we can conclude that the Abkhazians did not come from nowhere, they have lived here since ancient times and will hopefully continue to live here in the future if they manage to survive under the Russians.

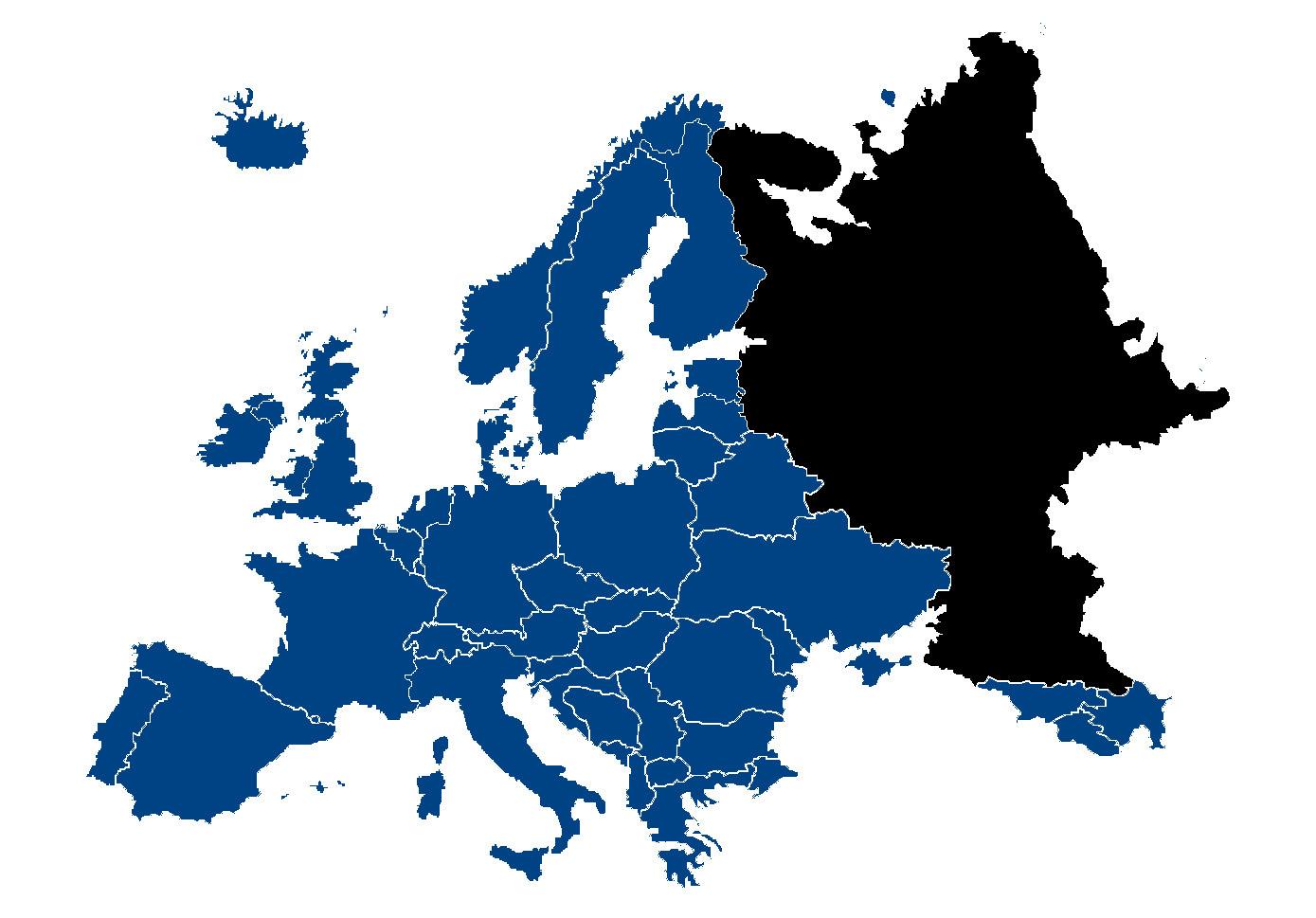

The names Abkhazia and Abkhazians entered Russian and European languages from Georgian (it is even more obvious that the names Ossetians and Ossetia also entered Russian and European languages from Georgian, with the Georgian suffix, -eti, having been retained). And those whom we call Abkhazians call themselves Apsu. Abkhazia is called Apsni in the Apsu language.

It is believed that the ancestors of the Apsu were Abasgians and Apsils, who are mentioned in Greco-Roman written sources of the 1-2nd centuries, but this question is not so simple. The Abasgians and Apsils were probably related, but still different tribes, since both appear separately in the same list of tribes. The difference between these two ethnic groups remained even in the Middle Ages.

The Life of Kartli, however, distinguishes Abkhazians and Abkhazia from Apshils (Apsaris) and Apshileti (Apsileti). It is emphatically written there that Tskhumi (Sukhumi) is in Apshileti and Anakophia is in Abkhazia; it is also known that on the territory of present-day Abkhazia the first king of the Kingdom of Abkhazia, Leon II, created two chiefdoms: the chiefdoms of Tskhumi and Abkhazia. The existence of two surnames, Apshilava and Abkhazava, confirms the difference of these two ethnic groups. The term Apshili must be a Maghrian pronunciation of Apsila, and Apshili is remarkably similar to the self-name of the present-day Abkhazians, Apsua.

In addition, in the note of one of the manuscripts of Life of Kartli, it is explained that the nickname Lasha of Queen Tamar’s son Giorgi, ‘the Enlightener of the World‘, was translated from the Apsarian language. The identity of Apsari, Apsil, Apsua is unquestionable for linguistics, and this identity is also confirmed by the fact that, according to the research of the famous linguist Ketevan Lomtatidze, the word ‘Lasha‘ means ‘lamp’ in the Apsu language. It is assumed that the Abasgoi, mentioned by the Romans as living in the Black Sea region, crossed the Caucasus in search of summer pastures for cattle and found fertile lands on the northern slope of the ridge, and part of the inhabitants of Abazginia settled there, and their descendants still live there under the name of Abazgi. The Abazginian language is very close to the Apsu language.

The Abazgs gained hegemony in the region in the early Middle Ages, and it is not surprising that their name has survived in the Georgian language as Abkhazia and Abkhazians to refer to the land and people of the Abazgs and Apsils.

The fact that Georgia is a multi-ethnic state is not a sign of its weakness, on the contrary, it is a sign of its strength. For centuries, all the ethnic groups living here have used the Georgian language to communicate with each other.

This was the case from the very beginning of the Kingdom of Kartli, as Leontius Mroveli confirms when he writes about the first King of Kartli: ‘Thus Parnavaz spread the Georgian language, and he did not want any other language to be used by the humble Georgians of Kartli‘. Even in the 19th century, when Georgia was part of the Russian Empire, Georgian remained the language of communication for the multi-ethnic population of Tbilisi.

If not the majority, until recently many Georgians considered Abkhazians to be Georgians. For the average Georgian, the fact that Abkhazians spoke a different language, which they did not understand, was no reason to alienate an Abkhazian or declare him a non-Georgian (after all, many Georgians do not understand the Megrelian-Laz, Svan, or Tsova-Tushetian languages). Abkhazians, at least the Abkhazian elite, also considered themselves to be Georgians. Giorgi Shervashidze (1846-1918), a member of a family of Abkhazian leaders, an associate of Ilia Chavchavadze, is widely known for his contribution to the development of the country. Here we cannot but remember the prototype of Tarash Emkhvari, the protagonist of Konstantin Gamsakhurdia’s ‘The Stealing of the Moon‘, Arzakan Emkhvari, Chairman of the Assembly of Abkhazia and participant in the Constituent Assembly of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, who led the democratic movement in Abkhazia with the slogan: ‘Let us unite not with the North Caucasus, but with Georgia!’

The ethno-cultural unity of Georgians and Abkhazians is reflected in the Georgian literature. Grigol Orbeliani in his poem ‘Toast‘ also mentions Abkhazians, known for their archery, as part of the army gathered in Didube under the flag of Tamar, along with Megrelians, Gurians, Imeretians, and Meskhs. Niko Lortkipanidze presented an impressive picture of the ethno-cultural unity of Georgians (Gurians, Imeretians, Megrelians) and Abkhazians in his story ‘Knights‘, which describes the war of the King of Imereti with renegade Abkhazians. It is noteworthy that in the story Agiashvili speaks to the Abkhazian boy in the Maghreb language. A Turkish figure of the 17th century, Evliya Celebi, who held a high position at the court of the Ottoman Sultan, was Abkhazian on his mother’s side and when describing his journey to his mother’s homeland, he noted that people living beyond the Enguri also spoke the Megrelian language. Evliya Celeb knew the Abkhazian language and therefore this information of his is absolutely reliable. Here one cannot but recall a wonderful poem by Akaki Tsereteli, ‘Gamzredeli‘ (Tutor), in which the Abkhazian Batu is madly in love with a Maghreb girl, Nazibrola, and marries her. While the girl considers the Abkhazian young man as a mediator between the heaven and the homeland. The poem clearly shows the communal and spiritual unity of Megrelians and Abkhazians, creating a common culture, which once again confirms the ethnographic and ethno-cultural unity of the Abkhazians and Georgians.

According to the latest anthropological research, the Apsu people do not differ from the Georgians, which is the result of centuries of co-existence between the two. This has been reflected in the ethnography of the Apsu-Abkhaz and culture in general, which Abkhazians and Georgians share.

Starting from the 4th century, Abkhazia became part of the Kingdom of Lazica. In the 6th century, during the Greco-Persian war, the Apsilians and Misimians apostate the Laz people. In the 7th century, Lazica and Abazgia were subordinated to the Byzantine emperor independently of each other. The Arabs then conquered Georgia in the 8th century. Together with the Kings of Kartli and Egrisi, the leader of the Abkhazians Leon I fought the Arabs at Anakophia with a 2,000-strong army. After the departure of the Arabs from Western Georgia, in the middle of the 8th century, the mission of reunification of the country was undertaken by the Abkhazian nobility. In the 80s of the same century, Abkhazian nobleman Leon II occupied the whole of Western Georgia, declared Kutaisi a throne city and received the title of king. Leon divided his kingdom into 8 principalities. Two of them were on the territory of present-day Abkhazia—the principality of Tskhumi in the south-east and the Abkhazian principality in the north-west, subordinated to Dzhiketi (Sochi-Tuapse district), where the Ubykhs, related to the Abkhazians, resided.

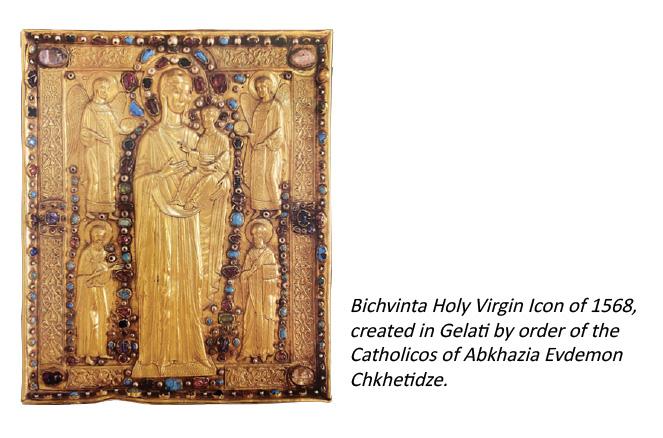

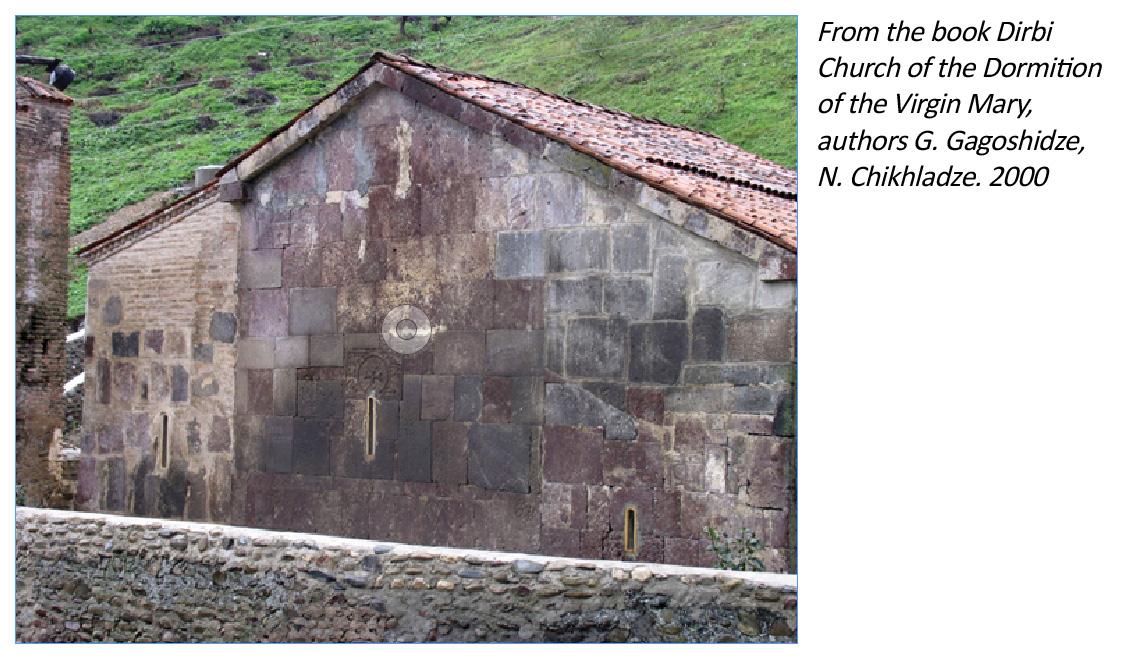

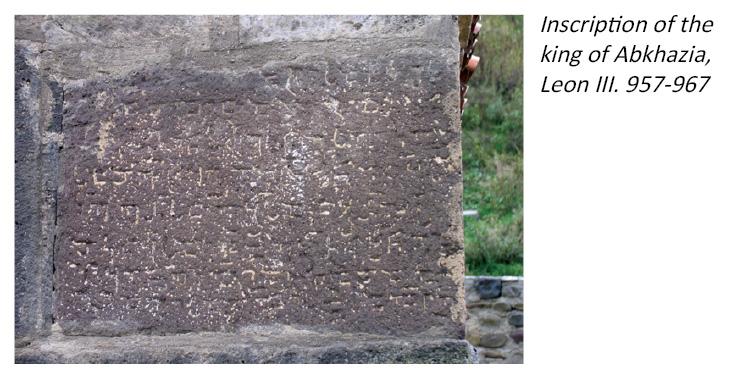

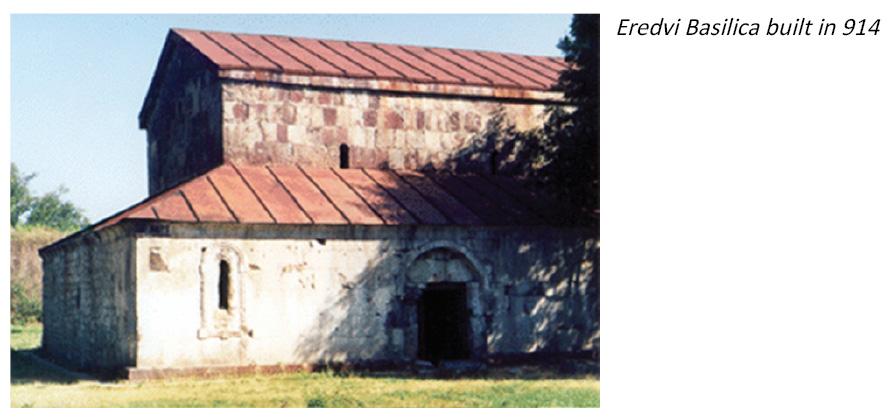

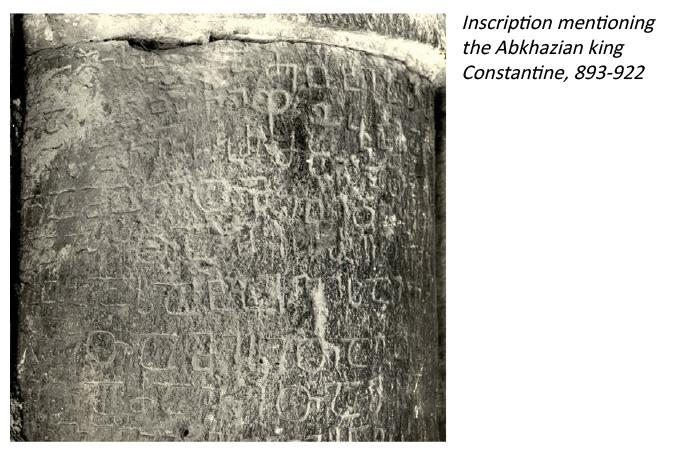

Abkhazian kings, if not ethnically, then at least culturally and politically, were as Georgian as the Kings of Tao-Klarjeti and Kakheti-Hereti, and together with them they were involved in the common struggle for the unification of their own country, Georgia. All the inscriptions made in the name of the Abkhazian kings and at their behest are Georgian without exception. Moreover, the oldest Georgian inscriptions have been preserved in western Georgia, in Gudauta, the hometown of the Apsua-Abkhazians.

All this shows how deeply integrated the Apsua-Abkhazians were with the Georgians. The fact that the language of culture, communication, writing, and prayer of the Abkhazians was already Georgian in the early Middle Ages is proven by the fact of how easily and painlessly the Abkhazian Church, which had escaped the control of Constantinople, merged with the Kartli Patriarchate in the 10th century and replaced worship in the Greek language with Georgian.

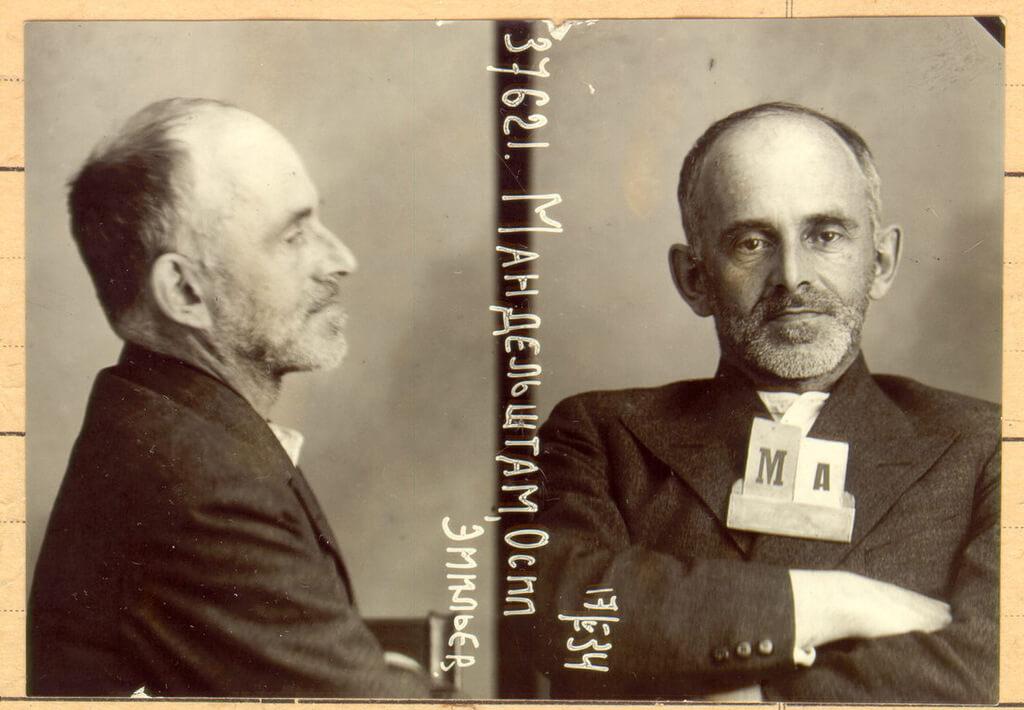

Even the disintegration of Georgia into kingdoms and principalities in the late Middle Ages could not break up the Abkhaz-Georgian unity. Despite hostilities and strife among themselves, all these political entities, including Abkhazia, considered themselves part of Georgia. But in the second half of the 19th century, Abkhazia was dealt a catastrophic blow, the consequences of which we are still reminded of today. In particular, in 1859, after the capture of Shamil, Russia began to conquer the Western Caucasus. Even worse, the Russian emperor decided to oust the local population from the Black Sea coast. In the spring of 1867, after the anti-Russian uprising of 1866, the Russians, in agreement with the Ottomans, deported the population of Tsabal, Dal, and Pitsunda, totalling 19,342 people, to Ottoman lands. Among the deportees were Georgians. The second stage of forced emigration of Abkhazians to Türkiye (known as the Mukhadzir) took place in 1877. The coast of Abkhazia, from which the Russians expelled 31,964 inhabitants, was almost completely depopulated, and the freed lands were distributed among Russians, Germans, and Greeks who had been transferred from Turkey. The Abkhaz people were saved from total annihilation by Georgian priests who baptised Abkhaz Muslims en masse, but the deportation caused irreparable damage to Abkhazia and the Abkhaz. The Mukhadzir mainly affected the lowland Abkhazian population, who were more civilised and integrated with Georgians than the highlanders. With their departure from Abkhazia, the thread of historical development was broken. The process of erasing the memory of the past among the Abkhazians, begun by Tsarist Russia, was successfully completed by the Soviet Union, which completely exterminated the surviving Abkhazian nobility that had preserved historical memory. People who have lost their historical memory are easy to manipulate, and Russia does it well.

In March 1921, the occupation of Georgia by Bolshevik Russia ended. The conquered country was divided into new units, and previously non-existent toponyms and autonomies appeared. Abkhazia was declared a socialist republic, but later returned to Georgia as an autonomous republic. Abkhazia was the only territorial entity on the territory of the former Soviet Union where the people who gave a name to this entity were a national minority, and the representatives of this minority had the highest right to occupy leading positions in the party and bureaucratic machine. This distorted social relations and disrupted social communication, contributing to the alienation between Abkhazians and Georgians. Many call this a kind of apartheid; in many ways ethnic privilege became the basis for the formation of a new society in Abkhazia, where being Georgian was not beneficial. This led to the hatred of Georgians by Abkhazians, which made possible the Russian-Georgian war of 1992-1993 in Abkhazia and unprecedented atrocities against Georgians on ethnic grounds, with genocide in Gagra and Sukhumi and the temporary expulsion of the indigenous Georgian population from Abkhazia. But that is another story, and we will return to it another time.