Author : Keti Kurdovanidze

When you lose something very precious, you can no longer find peace—you keep worrying, you get nervous, you search for it, you wait... and you hope you’ll find it and get it back. Then the emotion gradually fades, the contours become pale, it turns into a passive memory in which only a few details are alive. However, the emotional gradation associated with this phenomenon is accompanied by one strange thing: What you have lost becomes even more valuable. At such a moment, it is not the mere presence of the phenomenon, thing, or object that takes on significance, but the pain caused by its loss. Hence Hamlet’s question: What gives value to human existence—to be or not to be? Or even Vazha’s: ‘Dear death, life is valued by you!‘

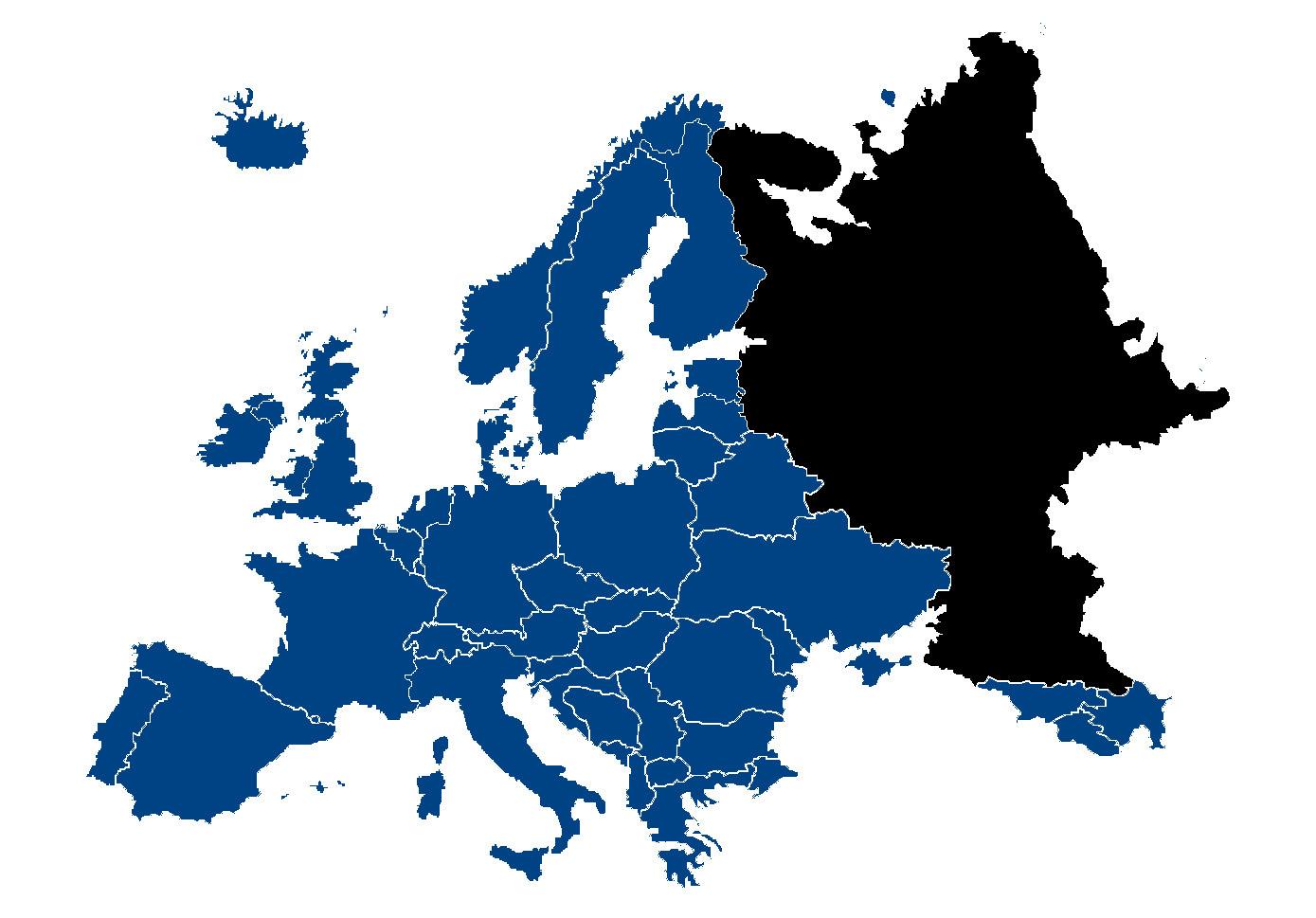

Thus, a special value was assigned to Abkhazia, which in our childhood was perceived as a place of fun, nonchalance, happiness, enjoyment of beauty, and peaceful rest for ‘native Tbilisians‘—a place in the ‘big house‘ where everything is there for your comfort, convenience and rest, which you love and cannot imagine that one day everything here will be damaged, destroyed, and alienated.

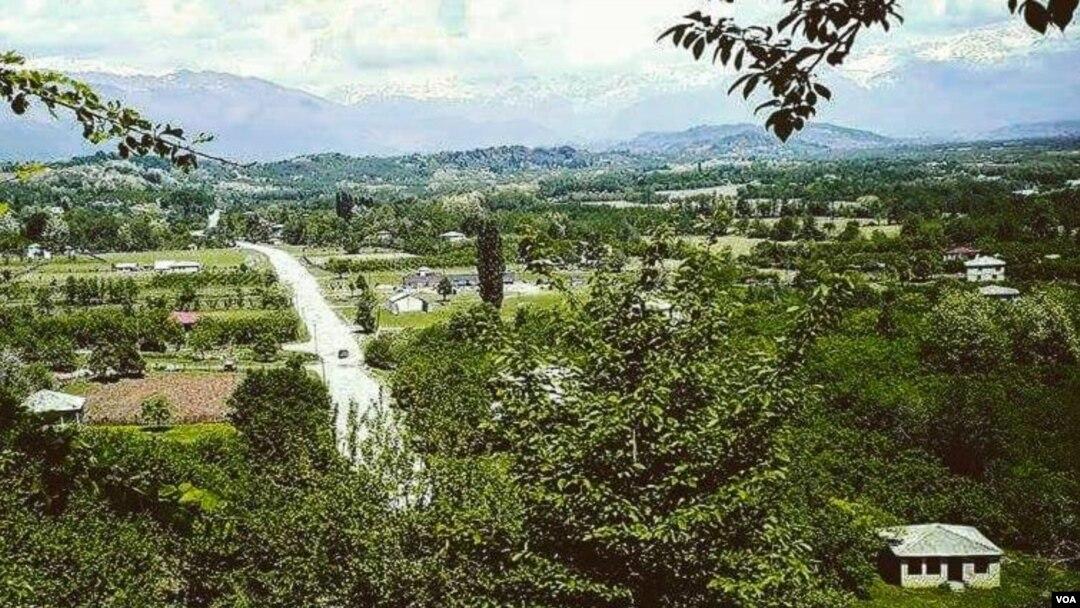

This is also what happened to us, ‘native Tbilisi residents‘, who, every summer, with a sense of social superiority, visited the shores of Pitsunda. Some stayed in the Literary Fund holiday home, some in the Creativity House, or Dom Tvorchestvo, and others in a multi-storey holiday home. We proudly embarked on two-week, and sometimes 24-day, trips, asserting our privilege, staying in ‘suites‘ located on the seashore.

Then the unpacking of suitcases, demonstration of clothes bought for fabulous money from black traders, a queue to the manicurist, a game of billiards and preference, and in the evenings parties and fortune-telling on coffee in the bar of the Russian Valya, who learnt from us that in Russian coffee is of masculine gender, and that chocolate, which was part of the Russian menu, is spelt with an ‘o‘ instead of an ‘i‘; completely pointless and meaningless small talk—who was whose lover, whose child was better than the other, and who had been to which capitalist country (because everyone went to socialist countries anyway).

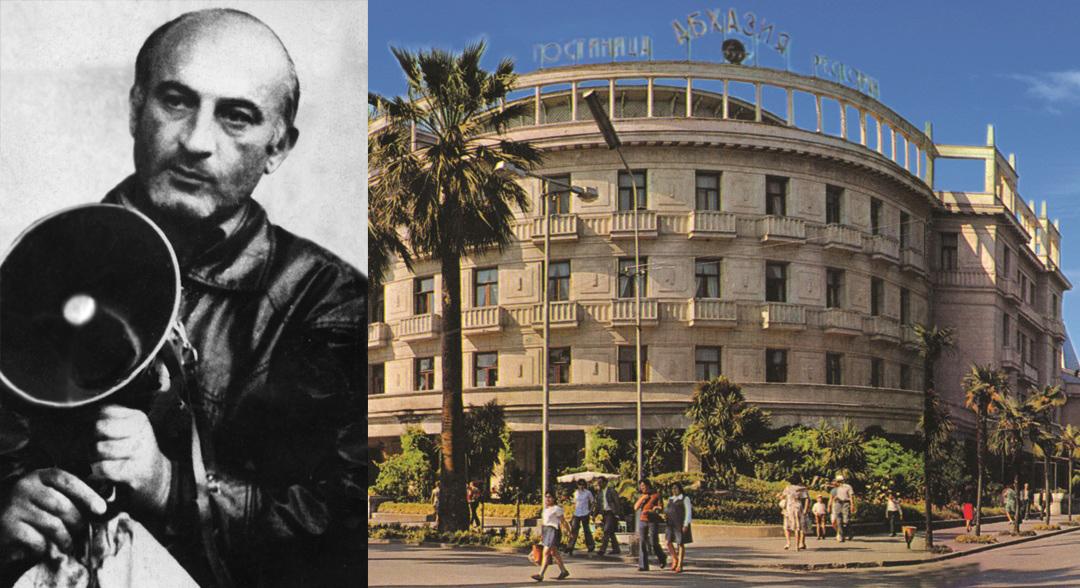

This is how Georgian Soviet culture was created in the Dom Tvorchestvo in Pitsunda, and this culture was nurtured, enriched, and supplemented by the unrestricted access of Russian artists to such holiday homes. Who only could not be seen here: Kostalevsky and Smoktunovsky, Gritsenko and Etush, Telichkina and Muravyeva, Gurchenko and Gogoleva with their children, grandchildren, husbands, lovers, and friends. Relationships and identification with Russians further increased the self-esteem and superiority of Georgian ‘cultural workers‘, especially if a Russian ‘cultural worker‘ praised you, or you took part in a Russian romance, or liked the odjakhuri floating in oil (because at that time the Georgian elite was not yet privy to the sophistication of French and Italian dishes). Here, the proud Georgian artists’ eyes would light up with a completely different joy. Then there were endless conversations, full of self-admiration and flirtation. Then came the recollection of last summer’s news, and then the senseless worry that Yakovlev had not been able to come to Pitsunda this year. This anxiety was crowned by a story, with a touch of worry, from some Georgian theatre actor about a prostate inflammation or the family peripeteia of this or that Russian actor. Lower-class artists would listen to this and then, on their return to Tbilisi, tell it to the first person of an even lower-class audience. Well, this is how the arts and the people developed.

It should also be noted that the ingrained habit of ridiculing and judging others had never left Georgian artists. Perhaps we should thank them for their ability to ‘think critically‘, otherwise what other force could have made the Georgian Soviet intelligentsia speak ill of the descendants of Pushkin and Lermontov? They would gather in the lobby—one who played the role of Shorena Kolonkelidze, essentially the minister’s wife, another who played Bechuni Pertia, the spouse of the creator of the ‘Book of Oaths‘; one more as the wife of the Oedipus star, who in reality was just an honourable citizen of Poti. Together, they’d embark on lengthy diatribes about Smoktunovsky’s son, the wrinkles on Gogoleva’s face, Gurchenko’s youthful paramour, or Telechkina’s short dresses.

What was remarkable about these conversations? It was interesting from a linguistic point of view as such discussions were conducted in the Georgian language (so that the guests would not understand or take offence), though the rest of the time the language of communication was Russian, so you could hear incredible Russian here. There were, of course, also the people proficient in Russian, but they were so few that it was hardly worth the effort to convey information about how they saw the world and what they wanted from it. Interestingly, they even made fun of those who made mistakes in the Russian language, often segueing into discussions by invoking the names of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky.

Russians stayed away from Georgians. After they had had their fill of drinks in the room, they would say goodbye to the grateful host and with a specially made ‘ukladka‘ (hairdo) they would go to the ‘tantsplashadka‘ (dance floor). The excited hosts would kill the sadness of parting with them in the restaurants, then everyone would return, and that’s when the fights and quarrels began. The gates of Tvorchestvo were closed at 12 o’clock, and after that, according to the internal rules, no one was allowed in. This rule did not apply to Russians, it was a convention. But the Georgians were severely punished: Two late arrivals meant expulsion from ‘paradise‘ with a wolf’s ticket. However, a considerable number of Georgians managed to come to an agreement with Guguli Nikalaevna, the director of Tvorchestvo. Her punishing hand sometimes struck young and not well-off couples who went for a walk. Guguli Nikalaevna did not like lack for attention and gifts. Yes, it was like that.

And yet morning would come as usual, the beach would gradually fill up with hungover vacationers who had had too much gossip and fun, and this vapour of vodka and fatigue was completely overridden by the calm sea and bright sun—picturesque Abkhazia, neither ambitious in its beauty nor proud in its purity. This fact has always existed and created the counterbalance that gave patience to endure the creative discourse of the Georgian artists described above.

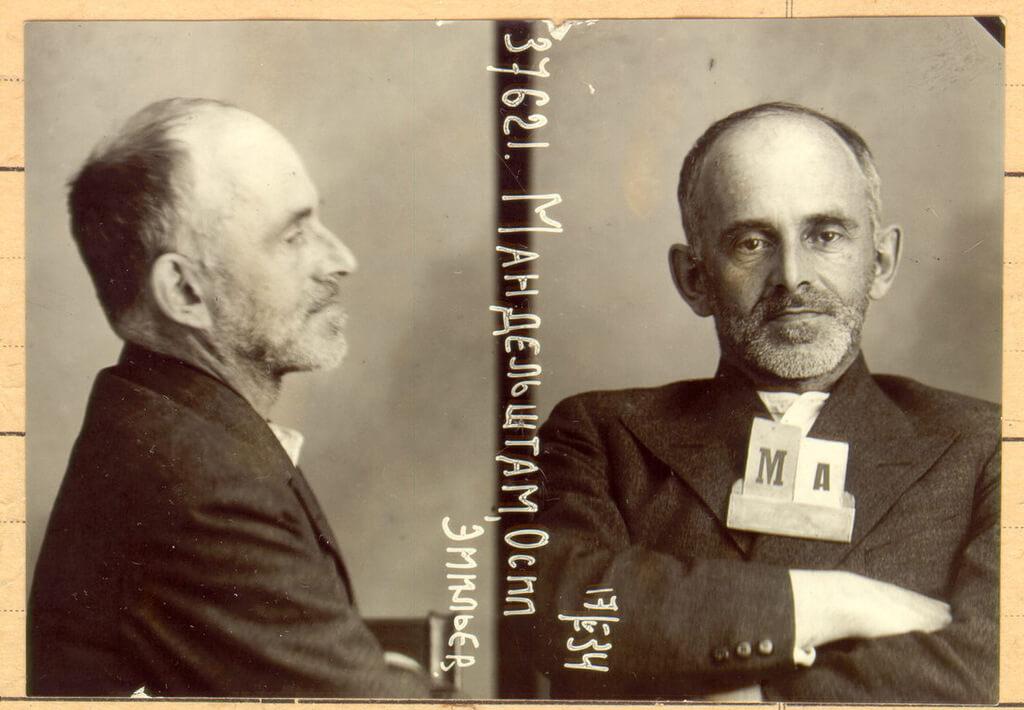

This Soviet cosiness, which was allowed here to please the artists, was sometimes disturbed by news such as the story of the aeroplane boys. Neither our society nor individual artists were prepared for moral dilemmas, so the decision to shoot an innocent priest and some rebellious youths hung over them like the sword of Damocles. I am talking about a moral dilemma, otherwise this morality would not have worked at all if, instead of the children of famous people, there had been girls and boys from Tsalendzhikha or Zestaponi on that plane. Well, our artists were out of luck—it would have been ugly to say no to the pardon of the children of colleagues and friends, but they would have had to pay dearly for the signature. In short, they found themselves between Scylla and Charybdis. And yet some signed, others withdrew their signatures and then justified it by saying that they would be shot anyway. Yes, they were like that.

The verdict was handed down on August 23rd, 1984, at the height of the Pitsunda season. A live broadcast of the trial was announced. Everyone gathered in the lobby of the Creativity House. The Russians were there too, watching Vremya (a Russian news programme), they had the Moscow channel on, and they were completely uninterested in the anxiety of the people fussing around them. It took a lot of effort to switch the TV to the Georgian channel (at that time there were only three channels to choose from). The Russians switched off the television and sat down in front of the now extinguished screen, making sure that no one took their seats. They sat in silence, and this silence said that the place belonged to them. We switched on the television anyway. The sentence was announced. There were sobs and loud cries, but nothing to indicate that the five men were to be executed. Then, one by one, the people began to disperse: Some went to the bar, others to the restaurant—just like in Ilya’s story ‘The Gallows’. In the morning no one remembered anything, neither screams nor sobs. Joy and fun continued.

Years will pass and Georgians will mourn just as indifferently and silently, without shedding a single tear, for the boys shot in the Gagra stadium, for the lost Abkhazia and the ‘white sanatorium’, consoling themselves with the fact that these two-week trips no longer exist, just as Soviet comfort no longer exists, so I will have rest in the Maldives, it will be even better.

Memory holds what is important to us. Memory connects us with what we loved and believed in, and what we loved, believed in, and cherished continues to gain clarity with time. So, what was Abkhazia for us—the sun, the sea, and a ‘white sanatorium’ full of Russians, or Galaktion’s exclamation: ‘My native land you welcome me, your old friend!’

This is what we have to answer for.