Author : Ilia Nikolaishvili

‘Considering the many experiences I’ve gained from the world, if I know anything for sure about morals and obligations, it’s all thanks to football. The little I understand about morality, I learned on football fields and theatre stages—the football field and the theatre stage were my true university.’ After this interview with Albert Camus, a journalist asked him, ‘And still, which was more important to you, football or the theatre?’ Camus replied without hesitation, ‘Football.’

Today, I would like to talk to you about the moral dilemmas that exist in Georgian football. Sometimes people avoid starting an article with a quote, but when it comes to morality and football, how can we not mention Albert Camus, a talented goalkeeper and a great man?

Camus said that football taught him life lessons that he did not learn anywhere else. He believed that football, unlike the hypocritical rules of politics and public life, is based on very simple and clear moral laws: fairness, loyalty to the team, and teammates, and, most importantly, solidarity and the ability to take responsibility.

In Camus’s football, there is no God and no ideological manipulation, but there is a kind of Sisyphus myth that the boulder must be delivered to its destination every time. And this is impossible without compassion, solidarity, support, and respect for your teammate.

Let’s recall those brutal days when, last spring, on Tbilisi’s central avenue, a Russian government with Georgian surnames used merciless force and cruelty to crack down on young people who were protesting against the Russification of Georgia, beating, injuring, and physically and morally abusing innocent, righteous people.

When widespread injustice prevails under an oppressive Russian rule, most people naturally seek sympathy and solidarity. In those days, we saw immortal examples of such solidarity directly among the beaten and repressed people. But this was not enough. Given the government’s brutality and the complexity of the task, freedom-loving people expected broad national solidarity from various layers and spheres of society. People particularly expected solidarity from Georgian football players, who had achieved unprecedented success for Georgia just two weeks earlier. They expected it because the people, the so-called 12th player had made a significant contribution to this success. In interviews, practically every player on the national team said that the victory would have been impossible without the energy they received from the people. The value of fan support was best described by Nika Kvekveskiri, who scored the decisive penalty. He recalled how the people’s energy entered his body and how great a part the fans played in his scoring of that historic penalty.

When the football players’ voices were becoming unbearably late, Giorgi Kochorashvili was the first to express support for the people. It wasn’t with a clear, resonant statement, but with just a banal Instagram Story showing a child and a European Union flag. But both the people and the government understood that this could be the beginning of a very important wave.

The authorities pooled all their malice, employed all their cunning, and, with the help of the dirtiest political manipulations, introduced into the national team, recently proclaimed as uniting the nation, a vile narrative developed in the Kremlin’s laboratories. The entire state mobilised to discredit the name of Giorgi Khochorashvili, the author of this very weak Instagram Story. Who could be quicker than neo-Bolshevik Kakha Kaladze (whose body, even in modern Balenciaga and Margiela trousers, resembles that of Dynamo Tbilisi footballer Chichiko Pachulia in breeches, a Chekist from the Beria era) in joining this shameful act? It was he who took on the dirty work of calling his colleague, a national team football player, ‘politically biased’ and a ‘UNM member’ because of his father’s political activities. In Russian-Georgian Dream propaganda, this is a synonym for a bloodthirsty villain.

This very fact became the first moral dilemma in the national team after that great victory. A dilemma that, instead of ending with a clear, dignified, and morally upright response, ended in shame. The team’s players responded to that dirty ideological manipulation, which, in Albert Camus’s opinion, has no place in football, not with solidarity, support, or the sharing of Sisyphus’s burden, but by burying their heads in the sand like ostriches. Just when we thought that the neo-Bolshevik Kaladze’s incredible vileness would be met with sharp statuses from ‘our boys’, the exact opposite happened: even Giorgi Kochorashvili deleted that Instagram story.

This was the first moral fall and shame for the football players hailed as ‘golden boys’. Except for one man, everyone remained silent. But that one man, Solomon Kvirkvelia, turned out to be the smallest of them all. He not only buried his head in the sand but publicly declared his support for Kaladze. With that, he truly threw himself into the garbage dump, if not of Georgian football, then certainly of humanity.

One of the main goals of violent Russian regimes is to prevent society from consolidating around values like freedom, independence, equality, and democracy. In just a few hours, that great football victory united the people in a way we hadn’t seen since the dawn of the national movement. This unity proved to be a deadly threat to the regime.

In more or less democratic countries, football success doesn’t necessarily mean a change in the existing political reality. But for regimes like the Georgian Dream, a nation united even for the sake of football is a real threat. In this happiness, the voice of propaganda and moral relativism is no longer heard as loudly as is necessary for a dictatorship. That’s precisely why the regime started using force. That’s why it needed to shed the mask it had worn since 2012 and openly set out on a Russian path.

In the context of new opportunities for European integration, national rapprochement and the weakening of polarization would have significantly diminished Russian influence on political processes. For this reason, the Kremlin’s Georgian emissaries pursued targeted escalation, as they needed to put an end to the country’s movement toward the free world. It so happened that at this point in history, football was found to have an important role. Therefore, the regime subjected the national team to a terrible moral test, which not a single player passed. From a moral standpoint, the failure to publicly support Giorgi Kochorashvili was the first fall for this generation of the national team. This was followed in the coming months by even greater cowardice, superficiality, heartlessness, and now, turning their backs on their own fans. The national team players violated the most important rule in the divine world of this game: the rule of reciprocity between fans and players.

In 2004, I went to Paris on a work trip to prepare a report on a match between Paris Saint-Germain and Saint-Étienne. The PSG fans had displayed a huge banner for their club’s players that read: ‘LE SOUTIEN VOUS L’AVEZ, ALORS RESPECTEZ NOUS’ (‘You have our support, now show us your respect!’). I wondered what they meant by ‘respect’ in return for their support. I asked a French colleague, ‘Let’s say Paris Saint-Germain loses the game despite the fans’ support; would that be considered a sign of disrespect? What exactly do they mean?’

He explained that respect meant playing with dedication, being loyal to the club’s values, and supporting the fans if someone treated them unfairly.

This is the main rule of the football world—reciprocity between players and fans. When you need support, I’m by your side, but you must respect me. There are countless great examples in football history when players, through their words and actions, defended fans who were victims of violence. The story of Zvonimir Boban, for example, is worth telling. During a fight between the fans of Zagreb’s Dinamo and Belgrade’s Crvena Zvezda, he physically confronted Serbian police to protect Dinamo fans. Instead of separating the sides and stopping the fight, the Serbian police attacked and began beating the Croatian fans. Boban was a great footballer, but he became an immortal legend and a hero that evening when he physically fought to protect his own fans.

In 2017, the Catalan Parliament illegally declared independence, in violation of the Spanish constitution. This move was followed by heavy clashes in Barcelona between pro-independence supporters and Spanish riot police. The police visibly used excessive force and brutally dispersed the crowd (though this brutality is a humane act compared to the methods of the Ivanishvili regime). At that time, the entire Barcelona Football Club stood up against this brutality and violence. There wasn’t a single player who didn’t demand an end to the violence with an explicit statement or who didn’t hold the Spanish government responsible for beating the people. Some of Barça’s Catalan stars didn’t even shy away from swearing. The ethnically Spanish Andrés Iniesta, who is by no means a supporter of Catalan independence, was one of the first to stand by his fans, regardless of his political views. Even Leo Messi, who had never spoken publicly about anything other than football before, had to speak out. All of Barça’s stars were saying the main message: they are beating innocent people in the Catalonia stadium, they are beating our fans. They are beating our fans, our people in Barça jerseys—the same people we’re supposed to meet tomorrow at Camp Nou. We will not allow anyone to beat our people. Either stop the violence, or come to Barça’s training ground and beat us too. This is the world of football, this great game!

But what did we see when the Georgian Dream’s Russian-style riot police were bloodying innocent people? We saw cowardly texts that were written and then quickly deleted. We saw even more cowardly Instagram Stories that didn’t even need to be deleted, as they vanish on their own without a trace after 24 hours. We saw the shameful silence of the team captain, Guram Kashia. I don’t know what he can do to wash away this shame. We saw four football players hired to participate in the Russian regime’s election video. We saw that in such a large team, not a single person was found who would refuse to take money from a modern-day Sergo Ordzhonikidze1.

The entire team watched as executioners bloodied their fans wearing their team’s jerseys. Every day they watch as a Russian oligarch cuts off their country from the free world, how he overthrows its sovereignty and independence, and how they are sinking into a Russian peat swamp, but, astonishingly, not a single person among them will say no!

Unfortunately, the fans are also to be blamed. There is no such thing as unconditional support. It’s surprising when you take on debt to follow your team to Germany, and when you return home, your idols turn their backs on you, ignore you, don’t support you when you shed blood defending your country’s freedom, and all when you need their support the most.

The sports media is a world of its own, never lacking in flattery but rarely asking critical questions.

I have no hope for the football players or the media. They will never change on their own. We, the fans, must change. You can’t ask anyone to act heroically like Boban. It’s also pointless to explain that sports and politics cannot be separated. They don’t understand, but we must at least make them understand that when their fans are having their bones broken, being crammed into torture machines, beaten to death, and spat on in the face, they shouldn’t be taking money from the creator of this hell. On the contrary, they should distance themselves from him in every way and scream until they lose their voices for the torture of their innocent fans to stop. This is the foremost rule of football!

It’s a bit late, but what can you do? Unconditional fandom must be replaced by the condition, “LE SOUTIEN VOUS L’AVEZ, ALORS RESPECTEZ NOUS”— “You have our support, now show us your respect!’”

And finally, a big thank you to Giorgi Tsintsadze and Tornike Okriashvili for doing the exact opposite of their colleagues and standing by their fans on those bloody days—on Rustaveli Avenue, where the fate of Georgia is often decided!

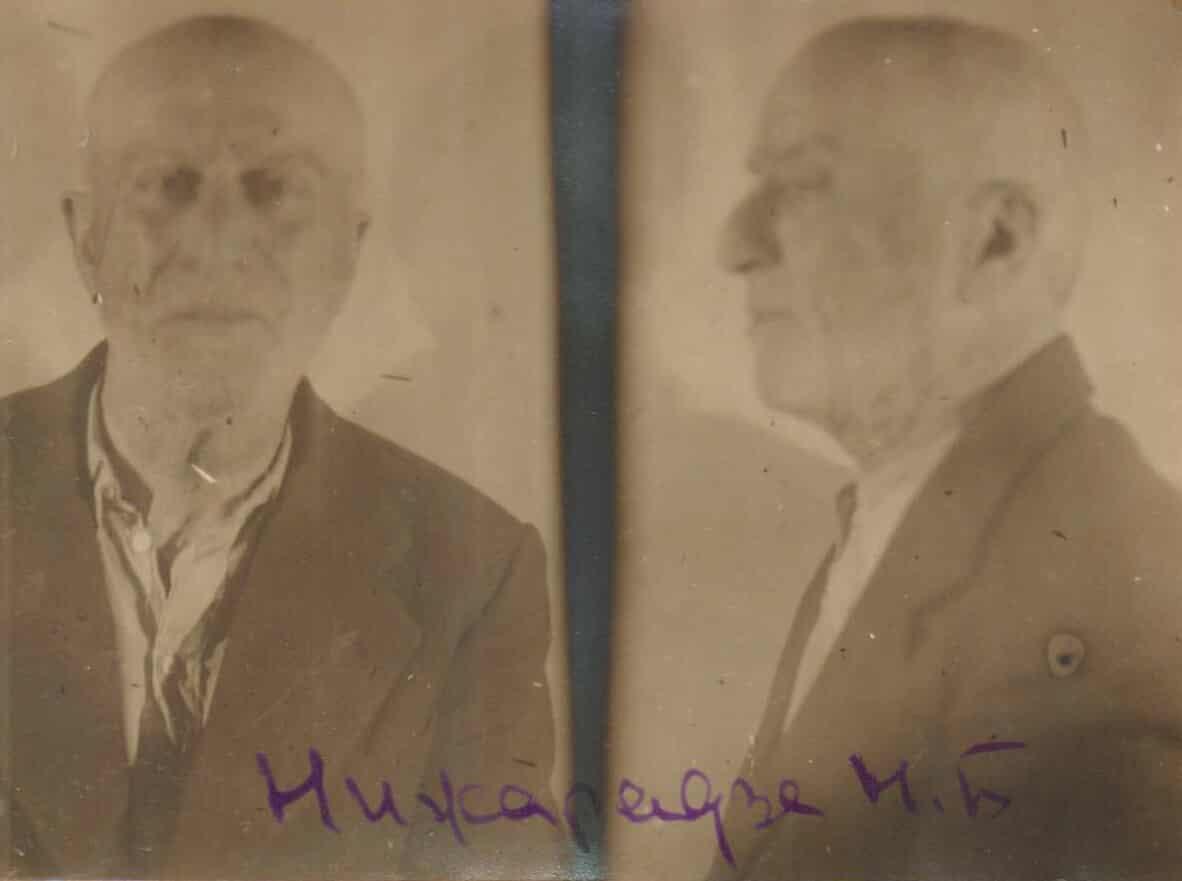

1. Sergo Ordzhonikidze (1886-1937) was a prominent Georgian Bolshevik and a high-ranking official in the Soviet Union. He was a close associate of Joseph Stalin and played a key role in the Bolshevik takeover of Georgia in 1921. He was known for his ruthless and uncompromising methods and was directly involved in the suppression of opposition and the implementation of Stalinist policies. He later died under mysterious circumstances, with some historians believing he was forced to commit suicide by Stalin. In the context of the provided text, his name is used as a historical parallel to an individual who serves as a tool for a modern, pro-Russian regime.