Author : Lasha Gabelia

There is no family in Georgia that was not scarred by World War II. Our country made the greatest sacrifice, with more than three hundred thousand dead and countless wounded and maimed—physically or psychologically. Many families ceased to exist, and many children grew up as orphans. After Ukraine, Georgia lost the most people as a percentage of its population in that meat grinder that Moscow propaganda called the ‘Great Patriotic War.‘ In Georgia, which had lost its independence, many truly saw it as a patriotic war, but the reality was that our country was once again crushed in the struggle between bloody empires.

‘For Georgians, being at the forefront of fighting is a rule!‘ This phrase, uttered by David Ulu in the 13th century, has served as a slogan for centuries, and in wars with the Mongols, Ottomans, Persians, and Russians, countless Georgian lives were lost in the defence and consolidation of those empires. The boundless energy and strength that should have been used for the prosperity of the homeland were lost and disappeared in distant battles.

The sons of a small country located at the crossroads of empires would be tossed by historical storms like a hurricane tosses small pieces of splinters at sea, throwing them from one shore to another. This is where the story of my grandfather, Samson Papiaashvili, begins, for whom World War II prepared the fate of such a splinter.

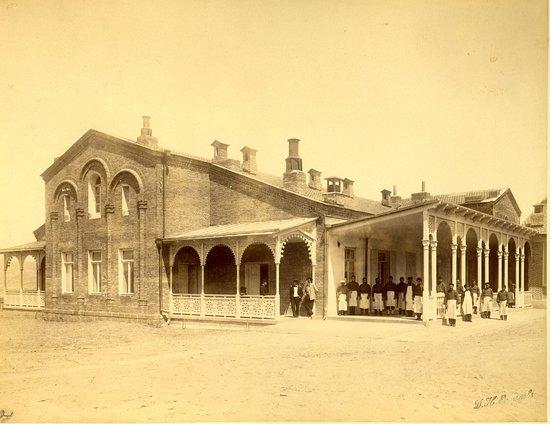

Samson was born in Sachkhere in 1913. From childhood, he showed an inclination toward art, especially singing, and he had a good voice and a good ear. He graduated from the Kutaisi Music School. He performed both Georgian folk songs and romances. In addition, he sang arias from operas (he had a wonderful tenor voice). He quickly became famous on a regional scale and even further. By 1939, he was already the director of the Sachkhere Culture House, the head of an ensemble, and a choirmaster. He was invited to Tbilisi, and his solo and ensemble songs were often played on central radio. also,he same time, he also engaged in pedagogical activities, and as his former students said, he taught not only singing and music but also, humanity. Samson already had a wife and two young daughters. ‘Not noticed‘ in dissidence, he lived the life of a happy Soviet citizen.

Samson Papiashvili, 1936.

Samson didn’t even protest: ‘If I do anything now, everyone will think I’m a coward.‘ It was December 1941. My grandfather took his panduri to the front…

He described what happened to him in a poem he called ‘My Short Adventure’. First, he ended up on the North Caucasus front, then in Crimea:

‘I still remember the merciless,

Fierce battles over Sevastopol,

The Black Sea—entirely stained with blood,

Groans and wails on the sea horizon.‘

The fight did not last long for him. In July 1942, right there in Crimea, his unit was captured by the Germans. Since Crimea was on the front line, they weren’t kept there for long. They were all transferred to a prisoner-of-war camp somewhere in the Carpathian Mountains, in western Ukraine (my grandfather doesn’t specify the location). Soon, a conspiracy was organized in the camp, and Samson tried to escape with fifteen comrades. They dug a tunnel under the fence and crawled through, but someone betrayed them. They were captured, and everyone was sentenced to be shot. One night, they were taken far from the camp to the edge of a forest. ‘And with our own hands, they made us dig the grave, to bury ourselves in,‘ my grandfather writes. They were made to stand by the graves they had dug, and a burst of machine-gun fire was aimed at them. By some miracle, as Samson himself tells it, a bullet did not hit him. But he jumped into the grave and feigned death. The Nazi punitive squad, it seems, performed their duty perfunctorily; they lightly covered the graves with soil and left.

When the sound of cars faded away, Samson crawled out of the grave and fled into the forest. He was the only one who had survived from those condemned to be shot. After wandering all night, he reached a village. Here, a family sheltered him, treated him, and helped him regain his strength. Samson does not specify their names or nationality, only mentioning a girl named Lina, for whom he developed ‘warm feelings‘, although he did not ‘betray‘ his ‘Mania‘ (his wife). My grandfather spent several weeks with this family, helping them with their village chores. They treated him like a family member; they grew very close and even took him as a guest to visit relatives in a neighbouring village.

The idyll could not last long, and during one of the Nazi’s next raids, Samson was captured again. This time, he was sent to forced labour—to a stone quarry, where they were made to work in harsh, open-air conditions. Interestingly, the prisoners were divided by nationality: There were many Georgians in Samson’s group, and there were Georgians among the overseers. My grandfather was not accustomed to hard physical labour, and it was very difficult for him, as he honestly writes in his diary poem:

‘Cutting trees, breaking stones,

It’s not my talent, it’s hard for me.

My business is merriment,

Dancing-singing, what a life.’

It was 1943. One day, as he himself writes, exhausted, he sat down on a large stone and started to sing: ‘They are late, they are nowhere to be seen‘... His song was so liked by the prisoners and overseers around him that they rewarded him with applause. The Georgian commander noticed this, and he reported the news ‘above’. They summoned him and told him: gather people like you, form an ensemble, entertain the prisoners and the administration, and you will be saved from hard labour.

Here, it is important to state the following: My grandfather was writing this poem-diary in Siberia, in the Gulag, under Soviet exile, and, consequently, much needs to be read between the lines. Clearly, the Nazis had seen in Samson not only the talent for singing but also potential that they could use. That’s precisely why they singled him out and gave him the opportunity to form an ensemble. The German authorities needed such activities for propaganda purposes, on the one hand: ‘Look how well we treat prisoners and conquered peoples, we take care of their culture, and so on.’ On the other hand, it was also to win over the hearts of the Georgian legionaries of the Wehrmacht. Thus, it was part of a political strategy. In addition to Samson’s ensemble, there were several similar groups, and not only made up of Georgians.

Samson’s ensemble ‘project’ was extremely successful. Soon, they were singing not just for prisoners of war but for the soldiers and officers of the Wehrmacht directly. Within a few months, they also began participating in regular civilian concerts, not only in Germany but almost all over occupied Europe. Samson describes the geography of their tours this way:

‘Every Frenchman, Italian,

Belgian, or Dutchman,

Everyone sends us off with glory and applause,

Hungarian-Pole and Austrian.’

That’s how my grandfather, born in Sachkhere, ended up on the stage of La Scala, where he performed Georgian folk songs and opera arias!

Samson Papiashvili (in the centre) with his choir. Neuhammer concentration camp, 1943.

They were not completely free, but they lived in better conditions than other prisoners. They had adequate living quarters, all kinds of musical instruments, and even Georgian national costumes (chokha-akhalukhi) for their concerts.

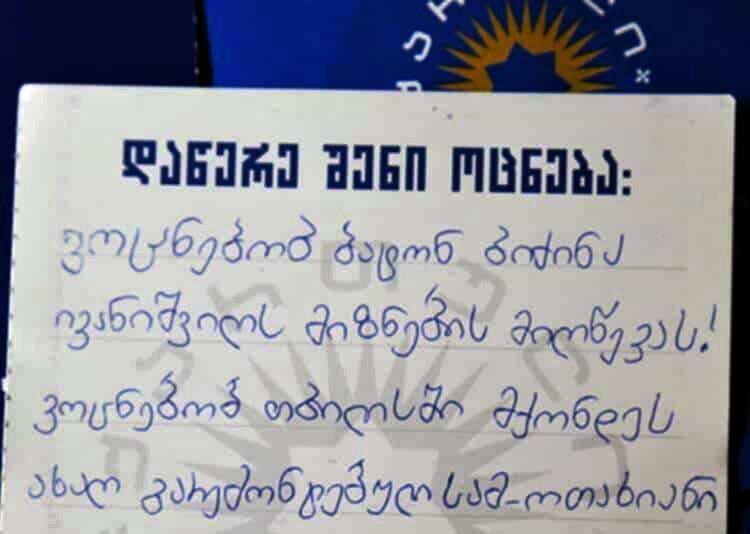

For example, on May 26, 1944, a solo concert by his ensemble was held in Berlin as part of the Georgian Legion’s events to celebrate Georgia’s Independence Day. The legion’s weekly newspaper, ‘Sakartvelo’, wrote about it: ‘In the evening, the city’s large theatre was packed with people. The choir of singers led by choirmaster S.P. (Samson Papiashvili) held a concert where old and new songs and dances were performed. The panduri playing was particularly good... Overall, the concert was a great success and was held with special acclaim.’

However, a dangerous situation arose several times afterward: For example, in France, Samson and the members of his choir made contact with the resistance movement. They were thinking of escaping. It’s not clear from the details what happened, but they were all immediately returned to Germany and threatened with being sent to a concentration camp. However, the threat was not carried out; they were placed in a military unit. Here, Samson was contacted by Davit (Datashka) Kavsadze (the father of the actor Kakhi Kavsadze).

‘They say that David Kavsadze,

He too has been captured as a prisoner,

His name all over Europe

Has become famous, just like mine.‘

David suggested to Samson that they merge their ensembles, and they did. A large Georgian ensemble was formed by the two groups, and their concert activity continued.

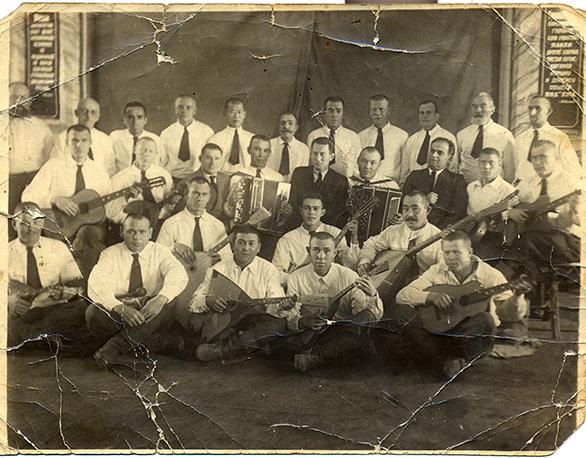

Datashka Kavsadze (third from left in the middle row) and Samson Papiashvili (fourth from left in the middle row) with Georgian singers. Germany, 1944.

Samson, for understandable reasons, does not write much about it, but it is clear that the Nazis’ lenient attitude toward him and his people was a result of the Georgian Legion’s protection.

The Nazis were already in trouble, and in the autumn of 1944, Hitler declared total mobilization. The mobilization of the captive singers’ ensembles, along with others, was on the agenda. This matter was led by Colonel Pridon Tsulukidze from the Georgian Legion, a former Menshevik who had fought on Franco’s side in the Spanish Civil War and was now an SS-Waffen-Standartenführer. My grandfather, with his ensemble, ended up under his command as part of the Georgian group of the Waffen-SS (SS-Waffengruppe Georgien)—they were first stationed in Hungary and then, from January 1945, in Northern Italy.

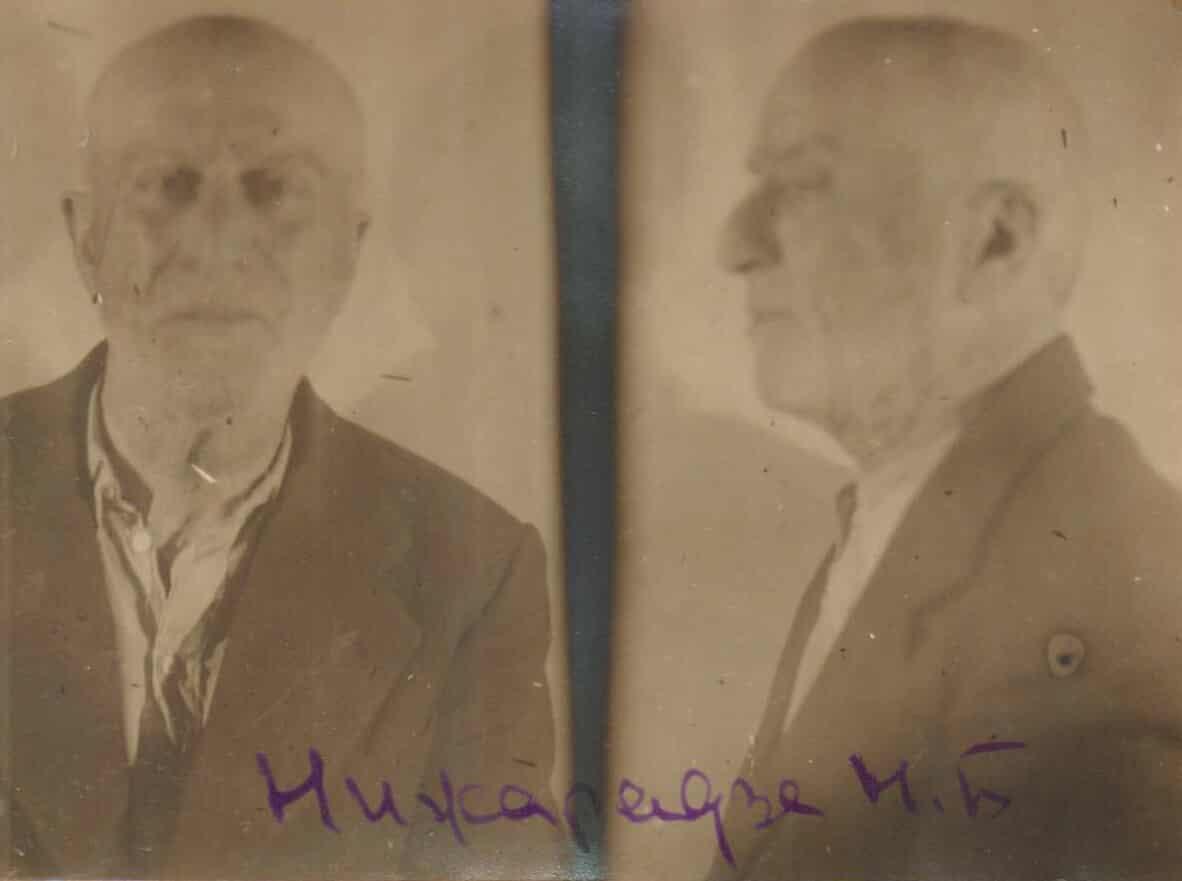

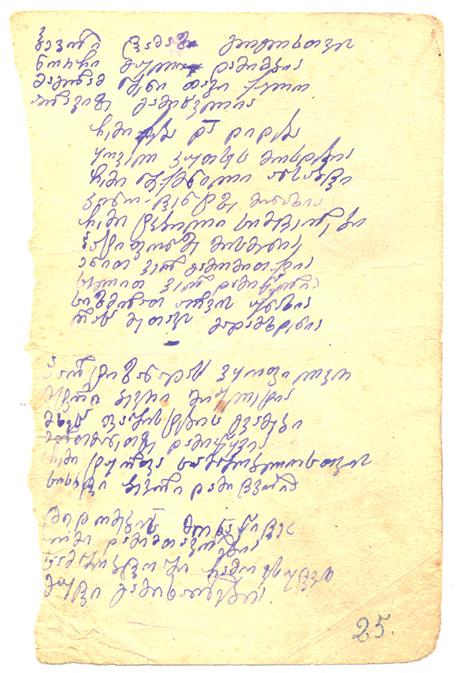

A page from Samson Papiashvili’s poem-diary

Everyone felt that the days of the Nazi regime were numbered. The Georgians conspired, and in March, everyone, including the leadership, defected to the side of the Italian partisans. It was here, in some village in Northern Italy, that my grandfather lived to see the end of World War II.

His first thought, of course, was to return to his homeland. Many advised him to stay, warning him that nothing good awaited him: he would either be exiled or shot. However, his love for his homeland and his longing for his family and loved ones prevailed. Samson and part of his ensemble surrendered to the Soviet authorities (some remained in exile). A severe sentence awaited him, of course, given his past as a prisoner of war, ‘singer for the fascists’, and, although only formally, a member of the Waffen-SS. The hope of returning to Georgia turned out to be in vain. He was first sent to a labour camp in Tajikistan (specifically, Leninabad), where he stayed for a year and a half. Then, his charges were made more severe, and in 1947, a tribunal sentenced him to 25 years in exile. He was first taken to Kolyma and finally ended up in Zabaykalsky Krai—in Ulan-Ude.

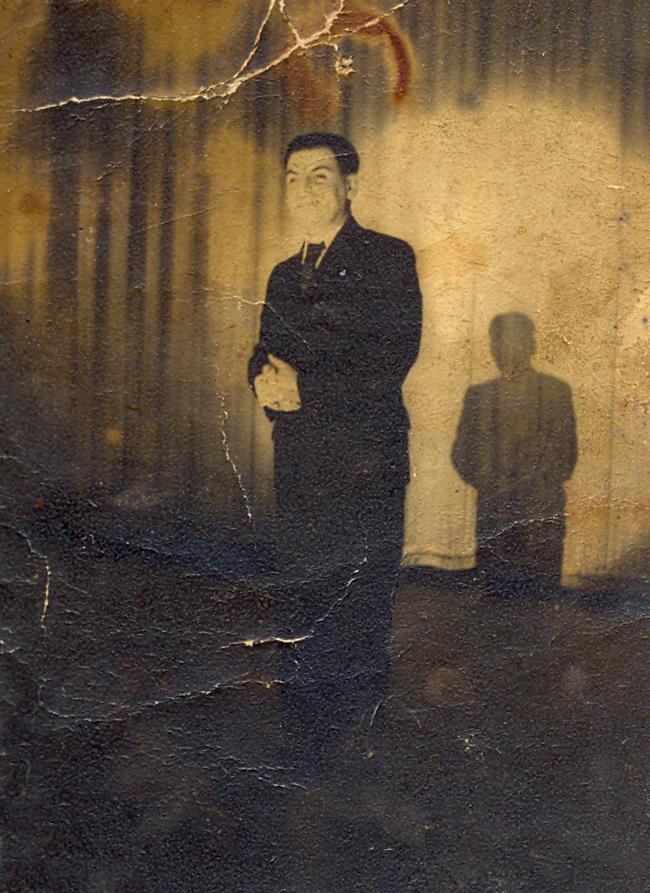

Samson Papiashvili (in a suit, right) with the ensemble formed in the Ulan-Ude camp. Circa 1950.

Life in the Soviet Gulag was much harder than life as a prisoner of the Nazis. There was frost, hunger, and violence. It was here, in Ulan-Ude, that Samson wrote his poem-adventure, which he dedicated to ‘the great Stalin’ in the hope of being released. He did not spare him any praise. Needless to say, this had no effect. Remarkably, Samson managed to form a choir of singers from among the prisoners in the Gulag. This choir was made up not only of Georgians; it was international and had an appropriate repertoire.

Samson spent six years in the Ulan-Ude camp, and his health gradually deteriorated. Only Stalin’s death granted him his freedom. At the end of 1953, he returned to his native land. People from Chiatura met him, and at the Sachkhere railway station, all Sachkhere was there to greet him. Everyone remembered him and his singing fondly. He was met by his wife and his now-grown daughters. Samson once again became the artistic director of the Sachkhere Culture House and continued his beloved work, although with his health in decline, he did not have much time left.

Samson Papiashvili on stage

Samson Papiashvili died of a heart attack on May 14, 1955, on the stage of the Krobouli village club, while singing. He left my grandmother—pregnant with my mother. He was only 42 years old at the time.