Author : Gia Gotua

Giorgi Beridze was twelve years old when tanks did not enter Tbilisi. He was born in 1980. His father was an engineer who worked at the Institute of Metallurgy, and like seven hundred thousand other citizens of Georgia, he was a member of the Communist Party. His mother was a teacher of Georgian language and literature and sympathised with the national movement. Giorgi’s parents often argued about politics; consequently, he disliked it.

In actual history, an armed coup d’état, instigated by Russia, took place in Georgia in December 1991, and the state collapsed. In the alternative history that we’re telling here, however, this event unfolded differently, to everyone’s surprise. Patriotism and reason overcame rivalry and greed.

In January 1992, in this alternative history, Georgia faces a backdrop of almost the same tension as in real history. Part of the former Communist elite and some activists of the national movement oppose Zviad Gamsakhurdia’s government. Traces of Russian activity are visible everywhere—the capital is slowly filling with weapons.

But something unexpected happens. In the first days of January, Eduard Shevardnadze and several influential members of Gamsakhurdia’s inner circle secretly meet in Moscow. Historians still argue about what happened and why the parties decided to de-escalate the situation. Some point to intrigues within the Russian government, suggesting that forces opposed to Shevardnadze were gaining the upper hand. In a bid for revenge, he decided to start his own game. Some analysts point to the role of Ukrainian mediators.

In short, the fact is that some kind of agreement was reached. The issue of privatization was probably the most important part of this deal. The nomenklatura received certain guarantees for the preservation of their property.

For Giorgi, this was good news. Life was already getting harder. Many things had disappeared from the store shelves and, consequently, from the dinner table. His parents were finding it increasingly difficult to make a living. Against this backdrop, there was one less reason for his parents to argue.

The agreement that was reached was not ideal. Later, many of the problems faced by the country would be attributed to it. However, it was definitely pragmatic. Gamsakhurdia was to remain in power until the elections at the end of 1992.

The privatization process was entrusted to the National Property Council, which had equal representation from politicians, economic leaders, and the so-called intelligentsia. It was no surprise to anyone that the majority of the property ultimately ended up in the hands of the nomenklatura.

However, the country was experiencing economic difficulties. Most factories had closed, and operating enterprises were producing far fewer goods. Against this backdrop of hardship, two television shows became particularly popular: Latin American soap operas and parliamentary debates. Parliamentary debates, which often seemed rather pointless, instilled some hope for the future in the weary audience.

By 1995, the Second Republic had taken on a distinct form. Zviad Gamsakhurdia’s supporters won the elections. In accordance with a previously signed agreement, they were able to enshrine several provisions in the constitution. Orthodoxy was declared the state religion. According to one of the articles of the constitution, protecting the rights of Georgians became the goal of the state. The basics of the Orthodox faith became a compulsory subject in schools. Social and demographic policies aimed to increase the number of ethnic Georgians and encourage them to settle in regions populated by ethnic minorities.

However, Gamsakhurdia and his supporters were unable to consolidate their power. According to the new constitution, Georgia became a mixed parliamentary-presidential republic. In the proportionally elected parliament, the ruling party faced strong opposition from two factions: the Democrats’ bloc, a complex and contradictory union of nomenklatura and activists, and the Regions Bloc, consisting mainly of MPs representing local elites who were elected by the populations of Abkhazia, Adjara, and Javakheti. According to political observers, both forces received support from Russia.

The regional elite’s representation in parliament often prevented useful reforms from being implemented on the ground. However, the presence of ethnic minority representatives in the same union also prevented ethnic and regional conflicts from being incited. Behind the scenes, Eduard Shevardnadze acted as an influential figure. The war in Samachablo came to an end, however a final settlement between the opposing sides was not possible, and the Tskhinvali region continued to exist as an unrecognised quasi-state under the ‘protection’ of Russian soldiers.

In 1995, Zviad Gamsakhurdia unexpectedly passed away. Despite the widespread reverence for his figure, his supporters lost the elections held the following year. The time had come for Shevardnadze.

The economy was improving. Trade with other countries was slowly expanding. In addition to Russia and other post-Soviet states, the country gained new trading partners. Tourism was also gradually growing. The discovery of new oil reserves on the Caspian Sea shelf became a significant turning point. The country came to the attention of the United States and Europe. Shortly before losing the election, Gamsakhurdia’s government had signed an agreement with the U.S. that involved building an oil pipeline through Georgia. Shevardnadze, who had secretly promised the Russians he would reconsider this agreement, was in no hurry to do so. Russia, too, was slowly approaching an economic crisis and didn’t have time for Georgia.

The ageing Shevardnadze no longer had the energy or willpower to do much. He was unable to cope with the widespread corruption within his inner circle and throughout the state apparatus. Controversy within his inner circle was commonplace—one might even say it was one of the levers of governance at his disposal. However, a confrontation was slowly brewing that he could no longer control. It was the clash between the team of so-called young reformers and the nomenklatura.

In 1996, Giorgi entered the university. He chose International Relations as his major, probably due to his mother’s influence. His father’s connections and financial resources were insufficient to secure him a place at Tbilisi State University. However, the private university he enrolled at had a good reputation. Many honest and qualified academics and staff found their way to Tbilisi Independent University. Rumour had it that the university was financed by one of the wealthy Georgians living in Moscow.

New players were also emerging on Georgia’s political and economic scene. From the early 2000s onwards, ethnic Georgians who had made their fortunes in Russia became increasingly involved in Georgian politics. In this context, five individuals in particular were mentioned, and their relationships were periodically tense. Shevardnadze was becoming increasingly powerless in the context of these developments. Many oligarchs were buying up land and properties at minimal prices from bankrupt or cash-strapped nomenklatura.

At that time, the opposition had been weakened. Regional leaders played only a nominal role within it. The Round Table coalition was weakened by sharp internal divisions. Nevertheless, Round Table structures played an important role in Georgian public life. They created a powerful network of activists, especially in the regions. These activists played an essential role in all local and national protests, becoming a formidable force for the local and national elite. This forced the elite to reconsider many of their decisions. It could be argued that the opposition also represented a Georgian version of civil society, playing an important role in public life.

The political landscape changed in 2002. The democratic bloc disintegrated. With the support of Western-funded NGOs, young reformers left Shevardnadze’s camp. The Round Table also finally split. Some of its activists joined the coalition with the young reformers. Dissatisfaction with the deteriorating economic situation and corruption was growing. A series of protests were held in the regions and in Tbilisi. Following the 2003 elections, the coalition of young reformers and Round Table supporters won. The coalition took two-thirds of the seats in parliament. This victory was not only determined by broad public support. Behind the scenes, the winning bloc had also gained the support of the regional elite and some of the oligarchs.

The new government was faced with many challenges. On the one hand, many issues required swift and radical intervention. On the other hand, the government relied on a broad coalition of supporters and had to consider the interests of the various groups within it. One such disagreement concerned the tough policy of combating crime and the planned changes to law enforcement structures. Despite the coalition’s broad consensus on the need to tackle organised crime, heated discussions took place regarding democratic control of law enforcement agencies. Implementing a zero tolerance policy caused some tension, particularly in the regions. Against this backdrop, opposition sentiments emerged not only among the general public, but also within the ruling coalition and among local activist groups.

Following several high-profile incidents and public discussions, a compromise was reached in early 2006. Within the coalition, a decision was made to shift the focus of efforts towards strengthening the independence of the judiciary. According to the agreement, the judiciary was to play a pivotal role both in overseeing law enforcement and in combatting crime.

Ultimately, reforming the police and criminal justice system became one of the new government’s most popular and widely supported moves.

Reforms in other areas did not proceed at an acceptable or pleasing pace for everyone. Thanks to the efforts of the new government, much of the country’s economic activity emerged from the shadows. Tax reform and policies aimed at attracting foreign investment also proved effective.

However, both the opposition and some members of the ruling coalition resisted reforming the state apparatus and privatisation. The government’s plans for saving and creating jobs were unclear. In the fight against corruption, some small entrepreneurs and state sector employees found themselves outside informal security mechanisms, causing dissatisfaction.

Ultimately, this debate also ended with a certain compromise within the government coalition. A strong component for small and medium-sized businesses was added to the economic policy. Relatively small but robust social safety mechanisms were included in the social policy. The issue of land privatization also moved forward, with politicians agreeing to consider both economic efficiency and the interests of local communities in the process.

Relations with the oligarchs were not simple either. Some of them supported the new government and preferred to operate behind the scenes, sometimes competing and sometimes reaching agreements with one another. One oligarch openly opposed the government and spearheaded the creation of a new opposition coalition, aided by his own television station. However, the opposition was not monolithic either. Gradually, opposition and civil groups that had emerged from within society also developed, including political parties, trade unions, community organizations, and others.

The new government pursued an active policy of decentralisation. Alongside the development of local self-governance, it began to decentralise the state apparatus. Some ministries were relocated to regional centres—for example, some were placed in Kutaisi, Batumi, and Sukhumi. This step was also part of a nation-building policy. The new government was trying to encourage ethnic minorities, including the Abkhaz, to play a more active role in the new, civic Georgian nation.

In terms of foreign policy, although allied relations with the West were strengthening, the main problem remained the relationship with Russia. The Kremlin was dissatisfied with losing its leverage inside the country, as well as with the new government’s active policy towards the Tskhinvali region. In 2007, an alternative administration for the Tskhinvali region was created with Tbilisi’s support. Some Ossetian villages came under the supervision of this administration. This presented a real possibility for the peaceful reintegration of the region into Georgia.

Confronted with this prospect and Georgia’s growing rapprochement with the West, Russia became concerned and began to develop invasion plans. Russia started to prepare the necessary infrastructure and conduct military exercises. Experts in Russia, Georgia, and Western countries actively discussed possible invasion scenarios. There was a broad discussion on this topic in the country, including on opposition channels. The first footage of Russian tanks entering via the Roki Tunnel on 1 August 2008 was shown on one of these small, independent opposition channels. From there, it spread to news channels worldwide, overshadowing the start of the Olympic Games in Beijing. Amidst the ongoing small-scale clashes between Georgian and Russian forces, an emergency meeting of NATO leaders was convened. Subsequently, French President Sarkozy first visited Moscow and then travelled to Tbilisi. The hostilities were halted.

In August 2008, Giorgi went to the recruitment office and volunteered for the army. However, by the time he was ready to go, the military action had already ended. At the time, he was working as a history teacher. After graduating from university, he had initially worked for a non-governmental organisation before moving to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. However, two years prior to these events, he realised that the most valuable thing he could do for his country was to be a teacher. Moreover, due to a successful education reform, the school had become a prestigious and financially secure place of employment. According to an ambitious plan developed by the Ministry of Education, by 2020 schools were supposed to have fully transitioned to a new model. Taking local specifics into account, this model resembled the Finnish school system.

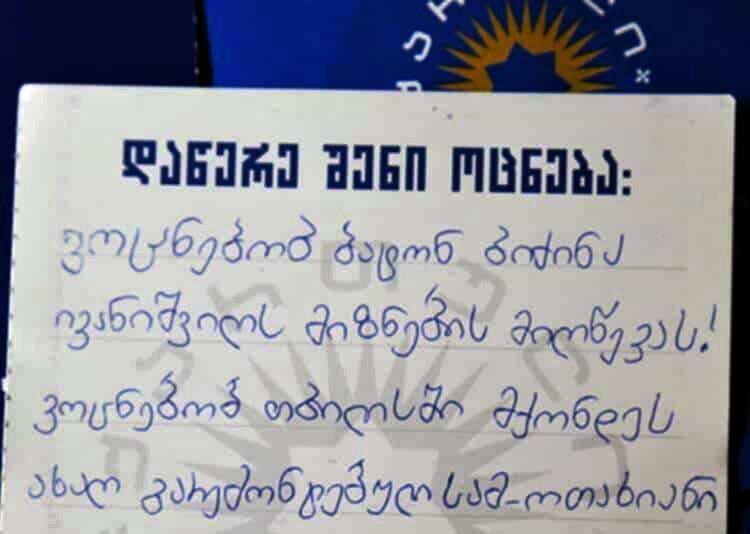

In September 2008, teacher Giorgi set an essay task for his eleventh-grade homeroom class. Students were asked to answer the following question in their essay: How would you assess Georgia’s development since 1992? One evening, Giorgi was sitting in the staff room. He was surprised and delighted to read an essay by Mari, a student who had recently joined the class. The essay ended like this:

‘It’s true that we lost a lot of time, but I believe that we still became a state. This happened because, at the right time, the citizens of Georgia stopped fighting for power and chose to serve the country instead.’