Author : Zaza Bibilashvili

When a Georgian sits down at the table, the first thing he does is raise a toast to peace—or so we are told by those who, before corrupting the very idea of peace, first stole the words ‘dignity’, ‘hope’, and ‘dream’ from us.

In reality, before a Georgian sits down at the table and toasts to peace, he greets his nearest and dearest with the word ‘Gamarjoba’.1 In this manner:

Gamarjoba to you!

‘Gamarjoba’.

Gamarjveba.2

For peace to prevail, victory must first be celebrated.

This is what our history, common sense, and our genetically encoded memory have taught us.

One must come to the table proud, joyful, and with head held high, to afford the luxury of toasting to peace—peace on your terms.

And for that one must be in the spirit of feasting and toasting.

For the defeated do not feast.

The defeated have no peace.

The defeated have only shame and fodder.

Those who seem to rejoice in defeat, those who justify submission to the aggressor, or profit from the mercantile slavery they chose for themselves are condemned, along with their shame and fodder, to live under the sincere contempt—a contempt that is an inherent part of enlightened patriotism, basic human dignity, and the civic virtue of ordinary citizens.

‘We are on our land, and you will be in it’—with this inscription, Ukraine greeted its barbaric enemy. It is with this spirit that Ukraine has fought and buried the enemy since.

And that is why Ukraine will prevail.

At a high price? — Of course!

This is precisely what the Georgian language Russian propaganda exploits: rubbing salt into historical wounds, awakening fears buried deep in our consciousness and feeding us dark conspiracy theories.

Yet it seems absurd to argue about the price of freedom in a country where sacrifice for freedom is the very flesh and blood of national identity—a country that has survived to this day without ever fearing such a price. It is indeed shameful to debate the cost of freedom with those whose worldview has been moulded since childhood by Rustaveli’s immortal words:

‘Death with dignity is better than a life of humiliation.’

If it had not been so—if we had not taken this path, if we had not prevailed—Georgia would not exist today, and the Gruzin Mankurts3 would formally be in the service of some other foreign power (not that they would mind or care).

Today, the petty peddlers who have lost all sense of shame speculate on the legacy of 100 thousand martyrs,4 Erekle II, and other glorious—or not-so-glorious—episodes of Georgian history. Some conceal their Russian epaulettes beneath clerical robes, preaching religious unity with the enemy. Others, disguised in civilian clothes, hide their motives behind false arguments of pragmatism.

Those are the ones who seek to base their legitimacy on heroic stories while simultaneously despising the very idea of self-sacrifice. They treat as objects of scorn the heroes who gave their lives for keep their motherland free—as shown by the vile remark of one notorious neo-Bolshevik about Giorgi Antsukhelidze,5 dismissing him as being ‘senselessly doomed for someone else’s PR stunt.’

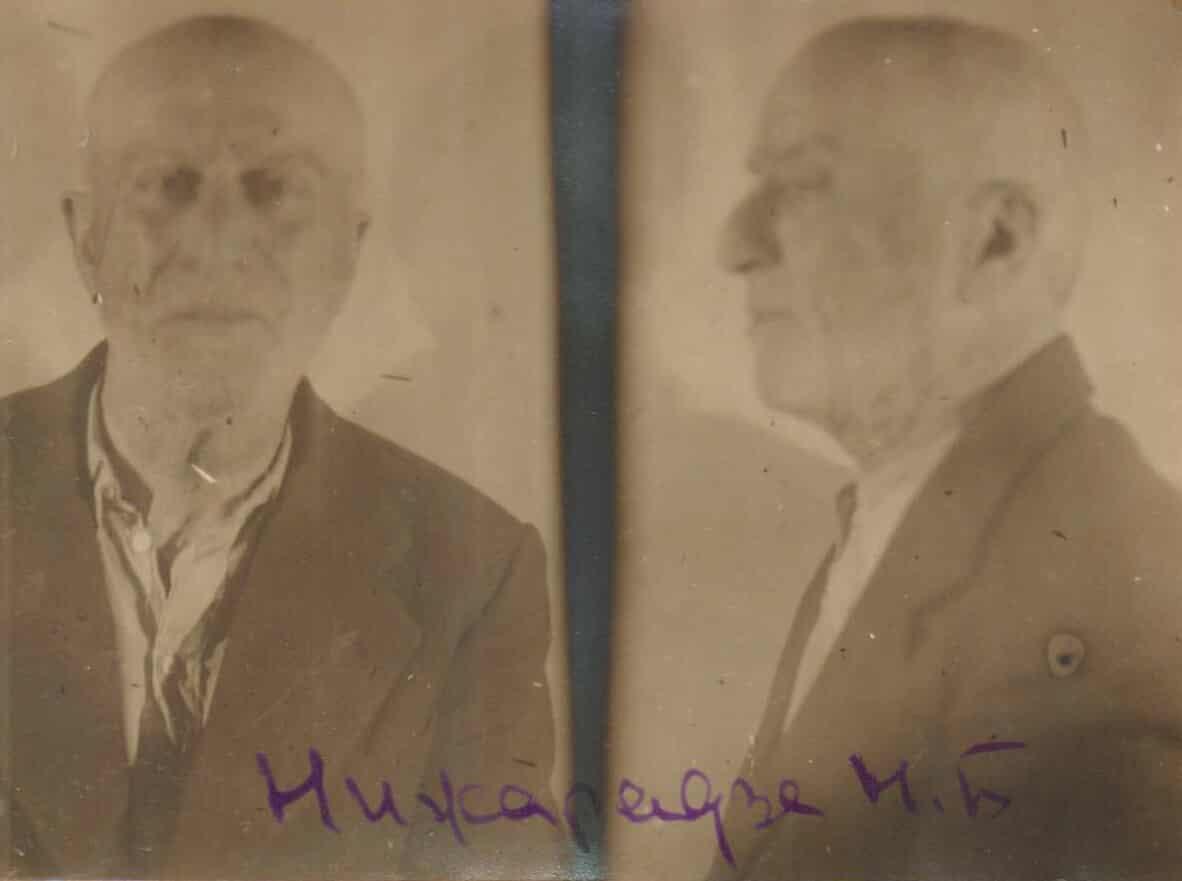

Those who created the Treason Commission.

Those who are in complete sync with Georgia’s only modern-day enemy, which occupies 20% of our country.

Those who fulfilled this enemy’s dream—not the hollow promises like ‘5 million for every village’, ‘free money’, or ‘a solarium for every family in Ureki’ (promises given by bidzina Ivanishvili during his 2012 campaign), but the real, rotten, anti-Georgian dream: by humiliating the Georgian state, exalting the most unworthy to positions of power, and apologizing to those who have committed a genocide of Georgians in Abkhazia.

Those who tell us that defending our homeland and attempting to expel the occupying state from our territory—even if we were to believe that we really did start that war – is a crime.

Those who have earned daily praise from the Russian proxies in Tskhinvali and their cynical patrons in the Kremlin.

...Have you ever wondered what price David the Builder6 paid for the unification of Georgia?

And Giorgi the Brilliant?7

And how many “beardless young men” did “Little Kakhi”8 put into the ground during his eighty battles before paying the price of not knowing Russia and trusting it?!

For us, free citizens of Georgia, the tragedy lies in the fact that those deprived of freedom alongside us feel no shame as long as there is enough fodder on their plates.

This is precisely why we must speak about this in Georgia, where dignified life and victory have always been, and still are, the only preconditions for real peace.

‘I will die, but I will not surrender!’—Have you ever noticed how much Georgians love to say that? How beautiful, how poetic it sounds! It is indeed a sign of an indomitable spirit.

But have you ever thought that those who sacrificed themselves have in fact lost their battles? They left us with heroic legends, but more often than not, they were defeated (of course, had we not fought and sacrificed ourselves, we would have disappeared, but that’s a whole different story).

And what we need, as much as air today, is victory.

Gamarjveba.

We must no longer idealize the notion of sacrificing ourselves for a noble cause. Our destiny is not to fall for glory, nor to measure our worth in the praises of those who wage war upon us. Let the enemy’s chroniclers compose their epics about how valiantly they fought against Georgians. Our task is greater. We must change our mindset. We must praise courage not from the ground of defeat, but from the height of victory. Let us be the ones who, from a position of strength, acknowledge the bravery of the defeated. For only then will we step out of the shadow of endless sacrifice and stand as the true authors of our own history.

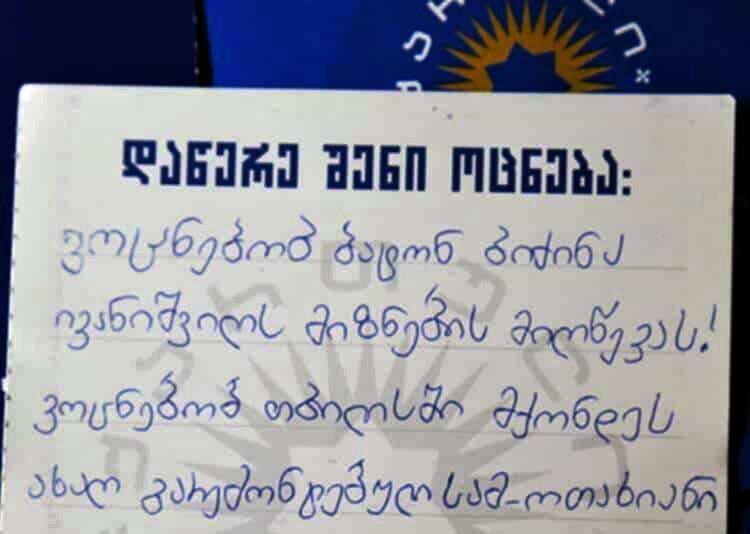

The tenth issue of New Iveria magazine is being released at a time when the illegitimate regime, acting on orders from the Kremlin, is waging a virtual war against Georgia’s most loyal friends, at a time when the entire opposition—both genuine and dubious—is in prison (in the best traditions of the KGB), the non-governmental sector is virtually paralyzed, the free media is on its last legs, and repression against the liberation movement is ongoing, all while the Georgian Dream party is carrying out a Bolshevik-style internal purge.

Is it any surprise that, by the 13th anniversary of the Georgian Dream’s takeover of Georgia, words have lost their original meaning or that reason has lost its appeal, giving way to primal instincts? And here, in the realm of instincts, the only thing that matters is victory in the struggle for survival. So, my dear Georgians, let us no longer think about poetically “sacrificing ourselves”, but instead prepare – and choose – to WIN.

1. The Georgian word ‘გამარჯობა’ (gamarjoba) is a common greeting that literally means ‘victory’. Its etymology is deeply rooted in the historical and cultural context of Georgia. This word is a noun derived from the verb ‘მარჯვება’ (marjveba), which means ‘to be victorious’ or ‘to win’. The greeting likely originated from a wish for victory, reflecting the country’s long and turbulent history filled with invasions and conflicts. By saying ‘gamarjoba’, Georgians were essentially wishing each other success and triumph over challenges, a sentiment that eventually evolved into a standard greeting of goodwill.

2. Gamarjveba means victory.

3. Gruzin, a Russian term for a ‘Georgian’ is used in Georgian as a word to describe those who fit the stereotypical Russian image of a Georgian who lacks civic virtue, social culture and personal ambition. Mankurts are unthinking slaves in Chingiz Aitmatov’s novel The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years. After the novel, in the Soviet Union the word came to refer to people who have lost touch with their ethnic homeland, who have forgotten their kinship. This meaning was retained in Russia and many other post-Soviet states.

4. The 100,000 Martyrs of Tbilisi were Christians massacred on 31 October 1227, during the Mongol invasion, when Jalal ad-Din, the Khwarazmian ruler, demanded that the citizens of Tbilisi renounce Christianity and embrace Islam. Refusing to betray their faith, they were executed en masse on the banks of the Kura River. Their martyrdom is deeply rooted in Georgian historical memory and is commemorated annually by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

5. Giorgi Antsukhelidze (18 August 1984 – 9 August 2008) was a Georgian sergeant who fought in the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. Captured during the Battle of Tskhinvali, he was tortured and executed by Russian and South Ossetian forces after refusing to kneel before his captors. His bravery and steadfastness became a national symbol of sacrifice and dignity. In 2013, he was posthumously awarded the Order of the National Hero of Georgia.

6. David IV, known as David the Builder (დავით აღმაშენებელი, 1073–1125), was King of Georgia from 1089 to 1125. He is celebrated as one of Georgia’s greatest monarchs, noted for unifying the fragmented Georgian lands, expelling the Seljuk Turks, and leading the kingdom into its political, military, and cultural golden age. His victory at the Battle of Didgori in 1121 is regarded as one of the most significant triumphs in Georgian history.

7. Giorgi V, known as Giorgi the Brilliant (გიორგი ბრწყინვალე, reigned c. 1299–1302 and 1314–1346), was a medieval King of Georgia. He restored the country’s unity after a period of Mongol domination, reasserted royal authority, and revived Georgia’s international prestige. Under his rule, Georgia regained much of its former strength, fostering political stability, economic growth, and flourishing cultural life. His reign is often considered the last great period of Georgia’s medieval monarchy.

8. Patara Kakhi was a nickname of King Erekle the Second of Kartl-Kakheti (Eastern Georgia), who ruled in the second half of the 18th century and was a feared military commander. He fought more than eighty battles against Persian and Ottoman forces, becoming a symbol of bravery and resistance. Surrounded by three major empires of the time, he managed to keep Eastern Georgia independent, until being lured into a diplomatic trap by the Russian Empire, leading to the loss of sovereignty three years after his death.