Author : Nana Kalandadze

As long as I can remember, I’ve lived in Mtatsminda, Tbilisi, and even if I ever change my house, I will still live in Mtatsminda in heart, mind, and spirit. But I was almost born in Vera. Here’s how the story goes:

My mother’s surname was Peikrishvili. According to history, most of the Three Hundred Aragvians1 were from this family. As an example of their fighting spirit, Tina of Tsavkisi, who was also a Peikrishvili, is worth mentioning. This surname is also common in Kakheti, and many people mistakenly believe that the Peikrishvilis are Kakhetians. However, they actually originate from the beautiful, dignified region of Meskheti, specifically the village of Khizabavra in the Aspindza area. There is also a toponym with this name near Lagodekhi, which the Peikrishvilis probably brought with them from Samtskhe. In short, some of the family settled near Tbilisi in Tsavkisi and devoted themselves to farming, primarily growing flowers, trees, and other plants. They transformed Tamar’s former summer residence and the Tsitsishvilis’ estates into a paradise.

The reasons why the Peikrishvilis relocated and became scattered across Kartli and Kakheti are probably recorded somewhere in history. The people of Tsavkisi were, to say the least, surprised by the ‘different’ nature of the new family. These Georgians wore crosses but did not go to church. If they did, they would make the sign of the cross in reverse. They prepared food a little differently. They grew flowers using a ‘different method’. But what’s so surprising about that? Every region has its own way of life and customs. But here, the influence of ‘non-local’ religious traditions could also be felt in daily life.

Georgia’s contact with the Catholic world dates to the 6th century (perhaps even earlier) and was quite close and businesslike. The Catholic Diocese of Tbilisi was founded in the 14th century, and the influence of Italian and French missionaries from the 17th century even changed the political pulse in Georgia. However, this is not my topic. What I want to say is that, under the influence of European missionaries, a significant part of the population of Samtskhe-Javakheti became adherents of Catholic Christianity, not to mention Giorgi XI and Sulkhan Saba Orbeliani... This fact had a significant impact on the lifestyle and character of the Meskhetians. They were even called ‘Frenchmen’. Moreover, European influences could be seen in their cuisine and cooking. I will never forget the cakes that my Aunt Maro used to send to her daughter Guliko (whose surname is Zubashvili, like Zubalashvili, and who is Catholic) from Akhaltsikhe in a huge box, when she lived with us as a student. It was then that I first tasted a croissant, which this extraordinary woman baked using a French recipe. No one knew the name of this culinary masterpiece, so they called it razhok or ragalik, having passed it through the Russian ‘filter’…

In this regard, I have my own theory about the famous Borjomi cakes, which were truly unique in terms of their content and quality compared to other confectionery products in Georgia. Perhaps the Samtskhe-Javakheti recipes and the French-European tradition of preparation also made it there? It’s not that far away... But I don’t know... Today, the descendants of these cakes are called ‘Lovika’s cakes’. I got sidetracked, but what I wanted to say is that, as a descendant of the Meskhetians, my grandfather was also baptised a Catholic. However, unlike his siblings, he converted to Orthodox Christianity. I strongly suspect he took this step because he was in love with my grandmother. By the way, there is a small basilica in Tsavkisi at the village crossroads. My mother said it is called the Peikrishvili Church, which suggests that the people who settled in this village were gradually adopting the ‘local’ way of life.

The people of Tsavkisi continue to engage in the gardening activities that have been passed down to them by their ancestors. A huge share of Tbilisi’s flower market comes from Tsavkisi. It’s true that this activity has become over commercialized, which has created a lot of reproach towards the locals, but in this beautiful village, you will also definitely meet real, professional gardeners who have elevated the cultivation and care of flowers to the level of art. So, it’s not surprising that my grandfather, a descendant of these people, was passionate about gardens and flowers—especially since he was apparently good at painting, too, and had impeccable taste.

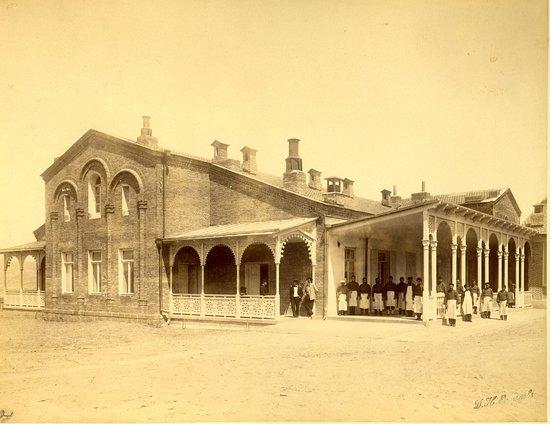

In 1896, when they decided to build the Udeli wine cellar for the royal estate, their attention was drawn to what was then a suburb of Tbilisi—now Melikishvili Street—and soon the idea was brought to life. Alexander Ozerov, an architect in Tbilisi at the time, who was very fond of this elevated location, designed the building using traditional Georgian church architecture. Who else but David Sarajishvili could finance the construction of such a project?

The building was quite large for a cellar, so soon the first winery was built there, where Georgian wine was subsequently produced for many years. The winery worked perfectly, but the building stood somewhat isolated on a hill, looking sadly at the Varazi Ravine. The area needed to be landscaped, which is how my grandfather ended up at the factory. In modern terms, my grandfather, a landscape designer, created a beautiful garden. However, it required a permanent caretaker. Traveling ‘so far’ from Sololaki every day wasn’t easy, so my grandfather almost moved to the factory. Later, an order was issued to develop the outskirts of Tbilisi. Plots of land were allocated to factory workers nearby where houses were planned to be built, and the area around the Varazi ravine, where jackals howled, was to take on an urban appearance.

Meanwhile, the construction of the Noblemen’s Gymnasium (later the first building of the State University) was in full swing on the opposite side. My grandfather, as a factory worker, was also allocated a plot of land for a homestead, but building a house would not happen overnight. Therefore, the family lived in Sololaki. My mother and her siblings also grew up and finished school in that neighbourhood.

Then the Vera house was built and the Peikrishvili family moved from Sololaki to the Varazi Ravine. My grandmother complained, ‘I lived wonderfully in the city. Now, how can I endure riding the tram for such a long distance?’ But she quickly got used to the new neighbourhood and neighbours. My grandfather worked at the Udeli factory and took care of every seedling, tree, and bush. Later, when my mother and I would walk past the factory, she would often say, ‘When the trees in that yard rustle, I think I hear my father breathing...’

The Varazi Ravine neighbourhood was slowly filling up with buildings and taking on a city look. Across from my mother’s house (where Nikoladze and Sharashidze streets are today), new construction was underway. Later, the members of my father’s family settled in one of those houses, although at the time, they had no idea that a girl living nearby would one day walk through the door of their apartment as a daughter-in-law.

The main residence and base of my father and the Kalandadzes was Chokhatauri. Then, a large part of the family moved to Tbilisi. After returning from Siberia, my father started building a new house in Guria. He probably wanted to settle there, but he returned from his second exile married and chose to stay in Tbilisi instead. Those who returned from Kazakhstan, however, were not met with good news. The government had settled another family in the Peikrishvili house and allocated a room at the back of the yard and a tiny corridor on the first floor to our family. Who’s talking about furniture and belongings? While the owners were away, everything was scattered and distributed. They were left with this dark ‘apartment’ and the two or three things that remained there.

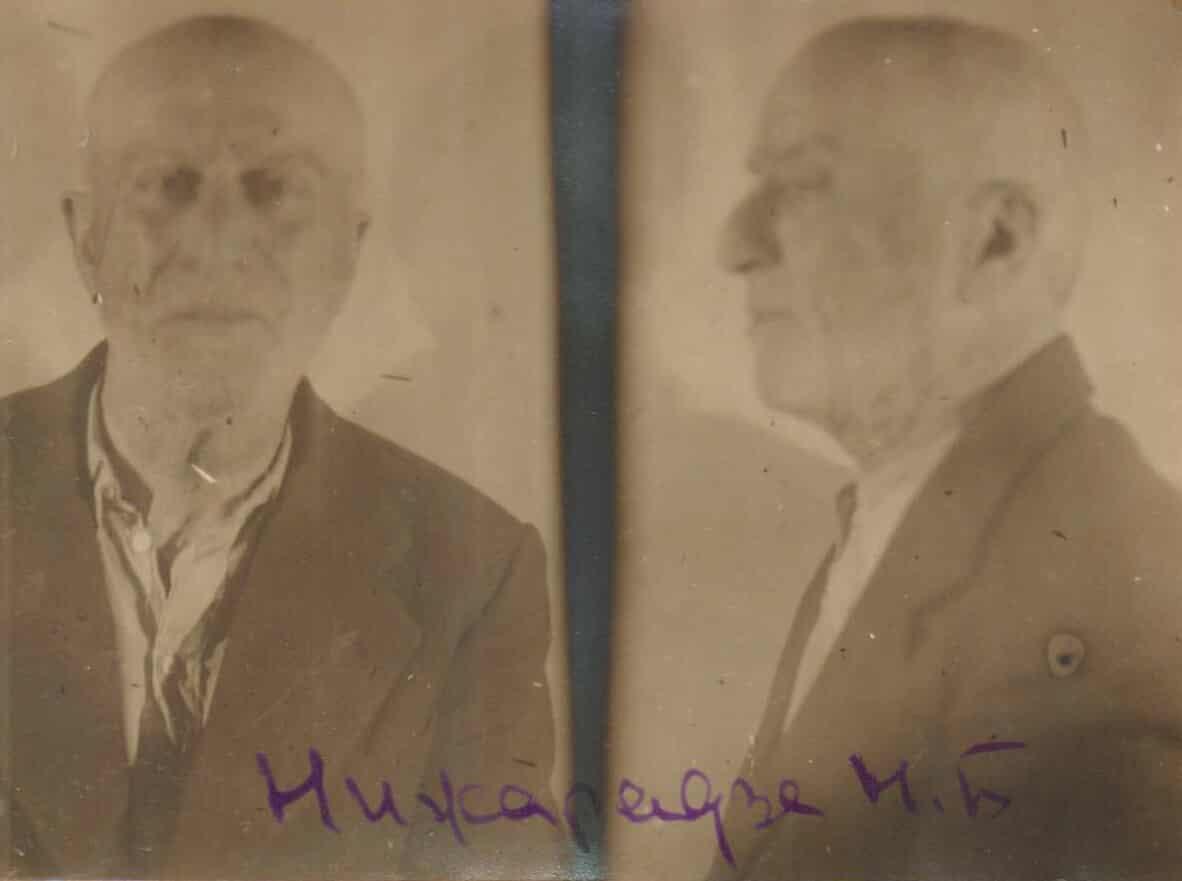

My grandfather approached the factory administration to see if they could help him on behalf of their organization. The factory authorities shrugged and said, ‘We allocated the land to you,’ (land that there is evidence had belonged to my grandfather), but what right do we have to interfere in domestic affairs? The reason was clear. After Stalin’s death in 1953, returning to Georgia did not mean people were fully rehabilitated. Who would grant them the status of a full-fledged citizen until their documents were re-examined and their lives were chewed over once again? I think they begrudged them even that measly room and reminded them that other “enemies of the people” would dream of having it. Meanwhile, my grandmother and grandfather, having endured so much stress and insult, passed away almost one after the other….

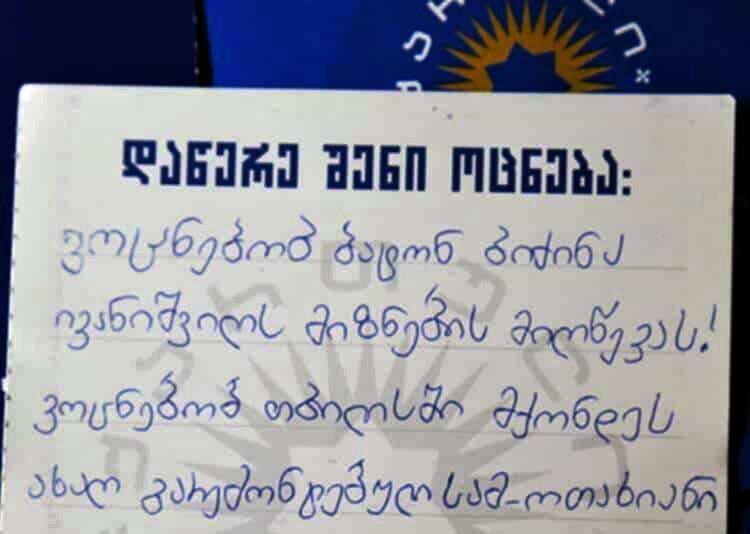

In 1956, they finally got a break, and my mother and father received a rehabilitation paper that contained two very important words: ‘Fully rehabilitated’!

My parents continued to fight vigorously to get their house back, or at least a couple rooms. But, in the meantime, the situation turned out completely differently. The government decided to ‘clean up’ the area and build a new five-story building on the site of our house and that of our neighbours’. They planned to compensate the residents according to the space they possessed. As you might have guessed, I’m talking about the arched building next to the former Tea House. That building doesn’t just have a façade, does it? The inner courtyard also belongs to it. So, they were given two rooms on the inner side that were dark and built against a solid rock wall.

Instead of receiving a proper homestead, albeit perhaps not large, the family was dealt another blow when they were given two dark rooms. They had to bear the name ‘enemy of the people’ for a long time because of family members who had exchanged the great Soviet Union for ‘rotten capitalist’ countries. Who knows what sorrow and pain swirled in the hearts of the ‘criminals’ roaming freely in France and Bavaria? A ruined house could not be restored, but my parents still hoped that they would gain better conditions.

One day, my father was informed that he was summoned to the executive committee. It was quite normal for him to be summoned to various authorities for questioning, checks, warnings, etc., so he went there as he would if he were going to work. To his surprise, he found himself in the office of a distant relative. This man had learned that a family was looking for an apartment, and he had an idea: a large family on Alexander Chavchavadze Street in Mtatsminda wanted to expand, and perhaps he could help him get this apartment through a double exchange. He said it was an old house, but it had large, bright rooms, and, most importantly, its own bathroom and storage rooms. The latter fact was particularly emphasized because, as is well known, living in so-called ‘communal apartments’ was common at the time.

Of course, my mother would have preferred a newly built house. However, she was so bothered by how narrow and dark the rooms were that the government had bestowed upon them that the Mtatsminda apartment seemed like a palace, and the deal was made. If you ask me, this apartment is the other extreme when it comes to lighting. It was once a school building, which explains the sheer number of doors and windows. In short, the apartment had two large rooms, one small room, a four-meter ceiling, a tiled stove, its own kitchen and bathroom, and a private, non-corridor entrance from the stairwell, which was even enviable at the time.

They settled and established themselves. Then, on October 12, 1958, I came into their lives.

1. The Three Hundred Aragvians were a detachment of soldiers from the Aragvi valley who, alongside King Erekle II’s army, fought at the Battle of Krtsanisi in 1795. This battle was fought against the invading Persian army of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar. The Aragvians are celebrated in Georgian history for their courage and sacrifice, as they fought to the last man to defend their capital, Tbilisi.