Author : David Khvadagiani

Nizharadze was a counterintelligence officer in the General Staff of the Georgian People’s Guard who carried out several important operations and became a real rage to the local satellite of the Russian Communist Party and Georgian Bolshevik underground. He was mentioned fragmentarily, only by surname, in various publications of the Democratic Republic of Georgia period, including the newspaper Kommunisti. His traces were erased by the Soviet occupation and emigration in 1921.

A century later, deciphering his identity became a difficult task for historians, as this common surname did not reveal his first name, position, or other identifying information. However, the important events in which a certain Nizharadze, shrouded in mystery, took an active part were such key and successful operations of the Georgian special services that gathering and tracking down information bit by bit made it possible to reconstruct the identity of this man, full of heroic and tragic adventures.

According to some reports, Nizharadze took part in the crackdown on a Bolshevik rally in Alexander Garden on 10 February 1918. The emigrant and former Social Democrat Porfiry Mekhuzla wrote about Nizharadze in his memoirs: ‘N. Nizharadze participated in the rally in the Garden of the Communards on the day of the salvo firing during the years of Georgia’s independence.’ It is therefore highly probable that he was assigned by the Guard’s General Staff at this time to coordinate with the Transcaucasian Commissariat’s special detachment, which carried out this punitive operation and thwarted the attempted Bolshevik coup.

From these fragmentary glimpses in the republic’s press and archives, we knew that, in 1918, Nizhradze arrested Budu Mdivani in Kutaisi. In the same year, he also arrested Tengiz Zhgenti in Tbilisi; Zhgenti had been living illegally in his cousin’s house near Alexander’s Garden. Also in 1918, he arrested Efrem Eshba, an Abkhaz Bolshevik who had come to Tbilisi to carry out illegal activities and was hiding at his girlfriend’s house.

The press also preserved the story of the robbery of road engineer Chkheidze, who was transporting 1,200,000 roubles in wages for workers on the Georgian Military Highway in the town of Pasanauri and was robbed by bandits on 9 March 1920. The investigation of the case was entrusted to the head of the criminal police, Platon Pachulia, to whom the General Staff of the People’s Guard sent Nizharadze as an assistant. Pachulia and Nizharadze solved the crime in the shortest possible time, arresting all the robbers and returning the stolen money.

Who was Nikoloz Nizharadze?

Nikoloz (Kolia) Nizharadze was born in 1888 in the village of Maghlaki, Kutaisi province. In 1903 he graduated from the Kutaisi Classical Gymnasium.

In 1904-1907 he studied pharmacy at the D.M. Kandelaki pharmacy in the city of Batumi and became a pharmacist.

In 1904, he became a member of the Social Democratic Party and was actively involved in political activities, and personally knew Noe Zhordania, carrying out his party assignments.

From 1908 to 1910, he worked as a pharmacist’s assistant at E.K. Okrinsky’s pharmacy in the city of Poti. From 1911 to 1913, he served as the manager of the pharmacy at the Supsa station in Guria. In 1914-1915, he worked as a pharmacy manager in Khashuri. From 1915 to 1918, he worked as the head of the pharmacy at the Lazaret of the Transcaucasian Union of Cities in Tbilisi.

While working in various parts of Georgia, Nikoloz Nizharadze continued his party and political activities. Following Russia’s February Revolution, the collapse of the empire, and soon after, the declaration of Georgia’s independence, due to his political experience, he was appointed as the head of counterintelligence in the newly formed People’s Guard.

The year 1919

Nikoloz Nizharadze was actively involved in one of the main counterintelligence operations carried out by the security services of the Democratic Republic of Georgia in 1919. The Bolshevik uprising of November 7, 1919 against the Democratic Republic of Georgia, which was directed from Soviet Russia, was defeated before it began. The Special Unit (Security Service) of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Democratic Republic of Georgia had successfully infiltrated one of its agents, Corporal Estate Pichkhaya, into the insurgent illegal headquarters, the so-called Garrison Military Council, which included 22 military personnel from Georgian army units stationed in Tbilisi who had defected to the Bolsheviks’ side.

Pichkhaia provided crucial information to the head of the Special Detachment, Melkisedek (Meki) Kedia. The secret headquarters, led by the Georgian Bolshevik Ilia Mgeladze (“Khoroghli”), who had arrived illegally from Soviet Russia, was arrested two days before the uprising was set to begin. The arrests took place in Room 15 of the Hotel Avrora on Vorontsov Square, where they were to give final directives to the military to incite an uprising in the Tbilisi garrison. Along with him, 22 military personnel were arrested. For the sake of conspiracy, Kedia also arrested his own agent, Estate Pichkhaia, who was released a few days later on the grounds of ‘lack of evidence’.

The arrested Bolsheviks smuggled a backup plan for the uprising and contacts for the ‘second echelon’ of illegally operating Bolsheviks out of prison with the help of the freed Pichkhaia. This resulted in the attempted uprising ending in complete failure. All the Bolsheviks involved in preparing the uprising were arrested. A similar situation developed in Akhaltsikhe and Poti, where the secret headquarters of the uprising was infiltrated by Georgian secret service agents and all Bolshevik leaders were arrested before the uprising could begin. However, the political leader of the Georgian Bolsheviks and of the uprising, Filipe Makharadze, managed to escape and continue his illegal activities underground.

The press box of the Founding Assembly, where Nikoloz Nizharadze sits with journalists and representatives of the nation.

On 30 November 1919, an interesting scene unfolded on Kojori Street in Sololaki, Tbilisi. After a secret meeting on Rtishev Street, Filipe Makharadze, who was disguised in a wig and a priest’s robe, was on his way to a conspiratorial apartment when he was arrested by Nikoloz Nizharadze, head of the counterintelligence department of the People’s Guard’s General Staff, and Mikheil Chkadua, a counterintelligence officer of the Guard. The operation was led by Levan (Leo) Rukhadze, who was a member of the People’s Guard’s General Staff and the head of the Information and Political Section.

From Filipe Makharadze’s safe apartment, the Guard’s counterintelligence unit seized all the important documents related to the Bolsheviks’ planned uprising. These papers directly linked the uprising to Moscow and revealed that it was financially supported by millions of roubles. The Minister of Internal Affairs of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, Noe Ramishvili, later presented a detailed report to the Constituent Assembly and provided significant information to Georgian and British journalists about the preparation and failure of the Moscow-organized uprising.

The year 1920

On March 1, 1920, on Andreev Street in Tbilisi, Nikoloz Nizharadze, head of the counterintelligence department of the People’s Guard’s General Staff, and other counterintelligence officers arrested the Bolshevik terrorist Pavle Mardaleishvili. Mardaleishvili had been wanted since September 13, 1919, when he and fellow Bolshevik Arkadi Elbakidze attacked General Nikoloz Baratov, a representative of the Russian Volunteer Army, on Vera Hill. Elbakidze was killed during the pursuit after the attack, while Mardaleishvili managed to escape. When he was arrested by the Guardsmen in 1920, a large quantity of explosives was found on him. Both Nizharadze and Mardaleishvili were originally from the village of Maghlaki, and the head of the Guard’s counterintelligence likely used his acquaintance with the terrorist as an additional means of surveillance.

Levan (Leo) Rukhadze - Member of the Constituent Assembly of Georgia, member of the Main Staff of the People’s Guard.

With this operation, the Georgian special services severed a highly important link in the detailed chain of war and sabotage planned by the enemy, Soviet Russia, which contributed significantly to saving Georgia from occupation.

In 1920, Soviet Russia was able to gain a decisive advantage on the front of the civil war. On January 2, 1920, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of Soviet Russia, Georgy Chicherin, appealed to the governments of Georgia and Azerbaijan asking to jointly fight against the Russian Volunteer Army. He was refused. On January 14, 1920, the Chairman of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, at a solemn session of the Constituent Assembly dedicated to the de facto recognition of Georgia by the Supreme Council of the Entente, stated directly that he had refused a military alliance with Russia because it would be a deviation from Georgia’s European path.

The Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan also responded in the negative to Russia. Since 1919, Azerbaijan had been party to a military cooperation agreement with Georgia, the purpose of which was to enable both states to defend themselves against the aggression of the Russian Volunteer Army.

Consequently, Azerbaijan refused to ally with Soviet Russia without the consent of Georgia. In March 1920, the Soviet Russian Red Army defeated parts of the Russian Volunteer Army in the North Caucasus, which were commanded by General Ivan Erdeli, and pursued them to the Georgian border. The Georgian government allowed the Volunteer Army units to enter only after they surrendered their weapons to the Georgian armed forces, in accordance with international regulations, and then let them pass abroad. The Democratic Republics of Georgia and Azerbaijan once again found themselves bordering Soviet Russia.

On April 28, 1920, Soviet Russia began its intervention in the Transcaucasus. Red Army units started an offensive towards Baku from the Samur River border zone. Azerbaijan found itself in a difficult situation. A large part of its army, about 20,000 soldiers, had been deployed in the Ganja-Karabakh direction to repel the invasion of the army of the Democratic Republic of Armenia, commanded by General “Dro”—Drastamat Kanayan. The Azerbaijani government could only send about 3,000 soldiers to the border battles against Soviet Russia, and a similar number of soldiers were stationed in Baku.

Bolshevik terrorist Pavle Mardaleishvili.

A significant number of high-ranking Georgian officers served in the Azerbaijani army, and the Georgian government was informed about the difficult situation in Azerbaijan. In accordance with the terms of the alliance agreement, certain units of the Georgian army advanced in the direction of Baku. However, the sequence of events unfolded with such speed, partly due to the Bolshevik uprising in Baku, that by May 1, Baku had fallen without serious fighting. In a matter of days, the Soviet Russian Red Army had advanced to the borders of Georgia.

The Georgian army and the People’s Guard successfully repelled the attack by the Soviet Union and subsequently initiated a counteroffensive. Notwithstanding the stipulations set out in the Russo-Georgian Treaty of May 7, 1920, which called for the cessation of military operations, hostilities persisted. The Georgian government’s emissaries, along with Georgian officers within the Azerbaijani army, were successful in their endeavours to incite an uprising in Ganja.

Concurrently, an uprising erupted in the Zakatala region under the leadership of a Georgian military intelligence officer, Major Ilya Ebralidze. This officer had assumed the guise of a trade agent, a tactic that enabled the Georgian armed forces to regroup. The Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, General Giorgi Kvinitadze, with six battalions of the People’s Guard and artillery, commanded by the Guard Commander Valiko Jugeli, successfully repelled the South Ossetian Partisan Brigade that had invaded from the rear, from the borders of Georgia.

Georgia survived. It is crucial to note that the Georgian government had advance knowledge of Soviet Russia’s extensive plans. Following the Soviet occupation of the North Caucasus, plans were made to proceed with the occupation of Georgia and Azerbaijan in a single move. In order to achieve this objective, preparatory work was conducted across the entire South Caucasus region. This included the planning of an attack on the military school in Tbilisi and the capture of the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia.

It was precisely within the scope of these preventive operations that on March 1, 1920, Nikoloz Nizharadze neutralized the Bolshevik terrorist Pavle Mardaleishvili in his apartment in Tbilisi as he was preparing a terrorist act. Mardaleishvili was storing explosives and living illegally under the false passport of Kirile Zhorzholiani.

Mardaleishvili’s plan was as follows: When the Soviet Russian Red Army occupied Azerbaijan and then attacked the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, he and his created terrorist group, which included Bolsheviks from Maghlaki, were to blow up the railway bridge at Rioni station. This would sever the Georgian armed forces’ connection with western Georgia and the seaports.

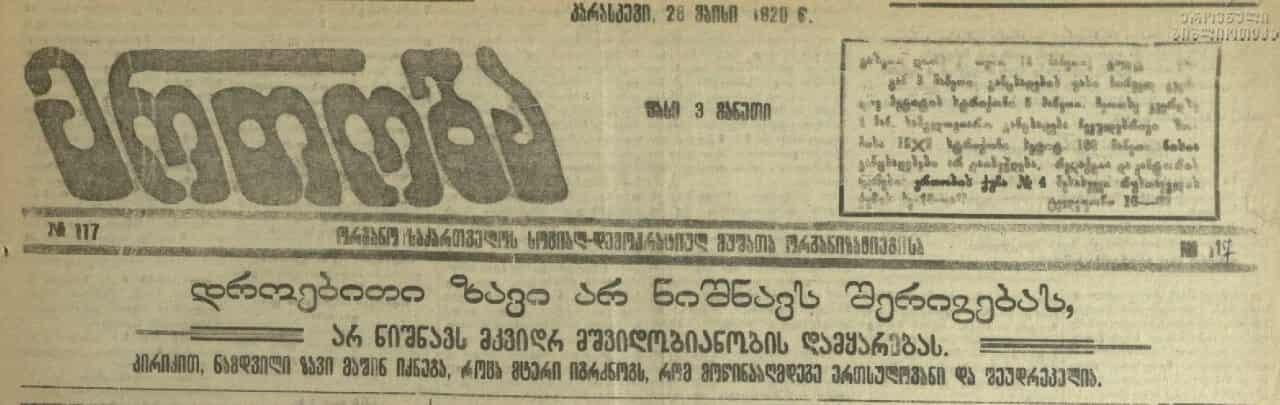

The newspaper “Ertoba” of the Georgian Social Democratic Party – May 28, 1920.

The Bolshevik Pavle Mardaleishvili was in Metekhi prison for only two months. He was released on May 14, 1920, along with other imprisoned Bolsheviks who were serving sentences after the failed uprising of November 7, 1919, based on the May 7th treaty. He then began working for the legalized Communist Party of Georgia’s newspaper, Komunisti.

The Soviet Russian propaganda mouthpiece, the newspaper Komunisti, which was first published on June 3, 1920, did not last long. The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Democratic Republic of Georgia shut it down after its 10th issue was released due to its declared support for the so-called South Ossetian uprising. In reality, this was a raid by the “South Ossetian partisan brigade” from Vladikavkaz, which was pre-planned in Moscow, a diversionary tactic against the Georgian armed forces during the war with Soviet Russia.

The first issue of Sakartvelos Komunisti (Communist Georgia), published on June 18, 1920, instead of the newspaper Komunisti, provided readers with comprehensive information regarding the closure of Komunisti by the Georgian government.

On Monday, June 14, from 11 a.m., employees of the Special Detachment of the Ministry of Internal Affairs surrounded the building in Sololaki that housed the editorial office of the newspaper Komunisti, as well as the bureaus of the Central Committee and the Gubernia Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia. They blocked all entrances and exits. Everyone was allowed to enter, but no one was allowed to leave. When Tumanov, the editor of the Komunisti asked what this sudden attack meant, the answer was: “We have orders from Kedia.”

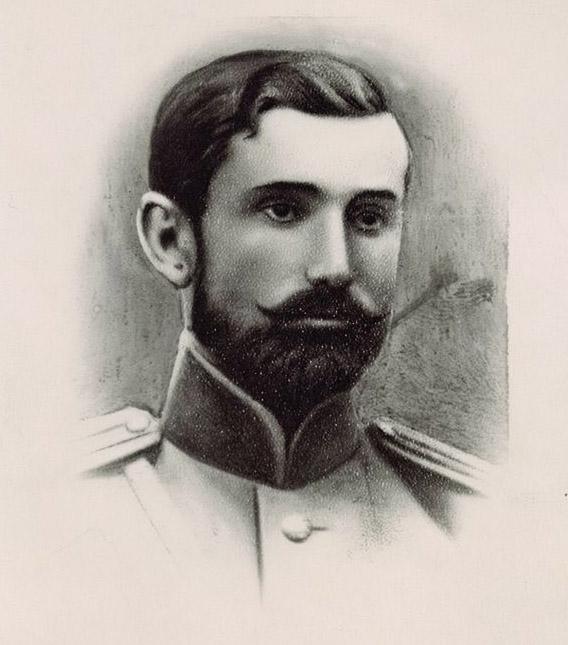

Colonel Nikoloz Ivanov

An hour later, Meki Kedia appeared and presented the editor with an order from Governor-General Sulakvelidze, which authorized Kedia to search the Komunisti editorial office and printing press and then shut down both. Additionally, he was to transfer the detained editor and staff of Komunisti to the Special Detachment.

Prior to the closure of the Komunisti editorial office by Kedia, he and Nikoloz Nizharadze, the head of the counterintelligence department of the People’s Guard’s General Staff, visited the Komunisti printing press. The press was closed down and the arrested employees were transferred to the Special Detachment of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The prisoners were released soon afterwards, but those who were not Georgian citizens were immediately expelled to occupied Azerbaijan, which was by then under Soviet Russian control.

On 23 June 1920, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Democratic Republic of Georgia issued an order for citizens who continued their illegal work in favour of Soviet Russia to leave Georgia within three days. Otherwise, they would be arrested again. The Bolshevik Pavle Mardaleishvili did not comply with the demand. He was arrested again by Nizharadze and returned to Metekhi prison.

The year 1921

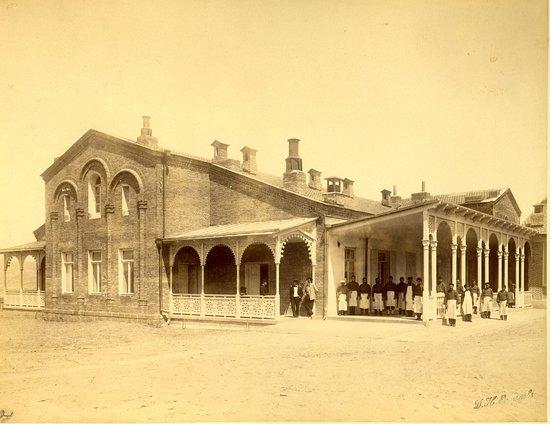

In the autumn of 1921, the Georgian government became aware of Soviet Russia’s plans. Georgia’s ambassador to Soviet Azerbaijan, Gabriel Khundadze, personally brought the 11th Army’s combat plan to Noe Zhordania via diplomatic train. The plan had been obtained by Georgian intelligence officers in Baku. The Georgian government, anticipating a Soviet attack, declared mobilization and began taking pre-emptive measures. This included the evacuation of 950 Bolsheviks who had been arrested in the summer and autumn of 1920 to Kutaisi Gubernia Prison, away from the front lines. The Bolshevik Pavle Mardaleishvili, who had been in Metekhi prison in Tbilisi since June 1920, was transferred to Kutaisi Gubernia Prison in early January 1921.

On February 11, 1921, Soviet Russia attacked the Democratic Republic of Georgia. After bloody battles, the capital, Tbilisi, fell on February 25.

A few days before the capital was abandoned, an arrested officer of the General Staff of the Georgian Ministry of Military Affairs, Colonel Nikoloz Ivanov, who was working for Soviet Russian intelligence, was transferred from Tbilisi to Kutaisi prison. On March 10, 1921, the Georgian government and armed forces retreated in the direction of Batumi. Before the evacuation, some of the Bolshevik prisoners from Kutaisi Gubernia Prison were transferred to Batumi prison. The Bolshevik prisoners learned of the Red Army’s approach and adamantly refused to be sent to Batumi, which made it necessary to transfer them by force. The evacuation of the Kutaisi prison inmates was assigned to Vladimir Sulakvelidze, the Head of the Rear, to whom the Special Detachment and all units of the People’s Militia were subordinate during the war.

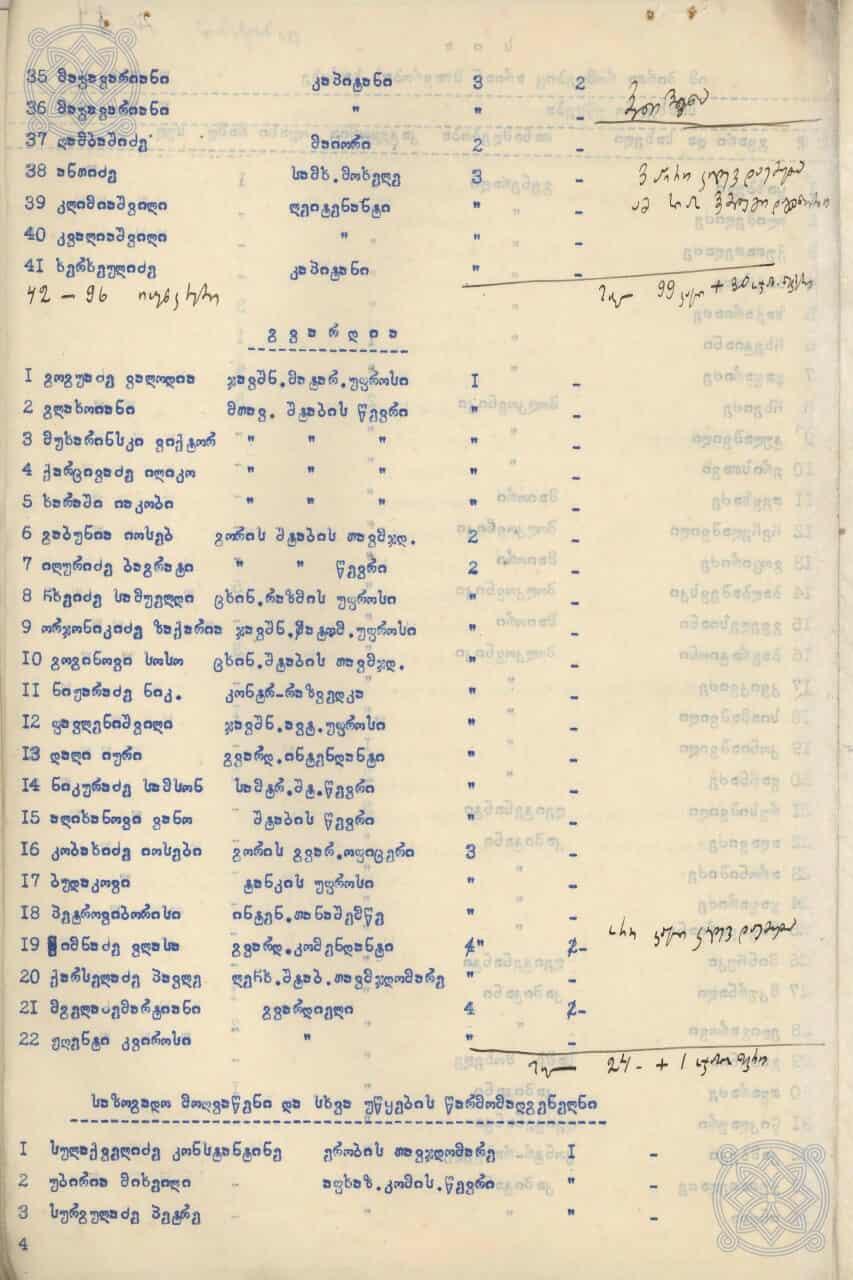

Fragment of the list of soldiers and guardsmen who emigrated in March 1921 - National Archives of Georgia.

On March 8, at noon, the Head of the Rear, Vladimir Sulakvelidze, the Head of the Kutaisi People’s Militia, Silibistro Maghnaradze, his deputy Valiko Pichkhaia, the Head of the Criminal Police, Platon Pachulia, the Head of the Kutaisi Criminal Police, Amberki Adeishvili, and the Head of the Counterintelligence Department of the People’s Guard’s General Staff, Nikoloz Nizharadze, arrived at the Kutaisi Gubernia Prison. Accompanied by employees of the Special Detachment and the People’s Militia, they severely beat the stubborn Bolshevik prisoners, forced them onto railway echelons, and transferred them to Batumi prison. On the night of March 9, Volodia Sulakvelidze and his companions arbitrarily took Pavle Mardaleishvili, Nikoloz Ivanov, and the criminal Davit Ukleba from the Kutaisi prison. They killed all three in the Saghoria forest, doused the bodies with gasoline, and burned them.

On 17 March 1921, the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia went into exile. They were accompanied by military and security personnel who faced an immediate death threat from the Russians, specifically from the 11th Army’s Osoby Otdel (Special Section), led by the sailor Vasiliy Pankratov, who was notorious for his cruelty. Among them was the head of the Guard’s counterintelligence, Nikoloz Nizharadze.

Like many other emigrants, he left his family – his wife and young child – behind in his homeland, with the hope that Georgia would soon be liberated from Russian occupation and they would return home.

Emigration

Nikoloz Nizharadze settled in Paris, France, and during the 1920s and 1930s, he lived the ordinary life of a Georgian political emigrant. At the same time, presumably like other colleagues, he continued to informally carry out special tasks for the legitimate Georgian government in exile.

In August 1942, Nikoloz Nizharadze, an emigrant residing in Leville, Paris, received a letter from his son, Akaki Nizharadze, who was then held in a German prisoner-of-war camp. Akaki Nizharadze informed his father that he had been taken prisoner during the Kerch disaster in May 1942 and was asking for help. Nikoloz immediately contacted Mikheil Kedia, the head of the Georgian Liaison Staff in Berlin. Mikheil, son of Meki Kedia, was former head of the Special Detachment and had worked there during the years of independence. Following the occupation, he went into exile, where he graduated from Heidelberg University. During World War II, he collaborated with the Germans with the aim of liberating Georgia from Russia. Mikheil Kedia facilitated Akaki’s release from the concentration camp, and a Georgian officer of German intelligence, Sinjikashvili, brought him to his father in Paris.

Akaki Nizharadze was born in the city of Poti in 1909. He graduated from school in Tbilisi and went on to receive a higher education. He was a journalist and worked as an editor of a regional newspaper. In 1929, the Soviet security agencies expressed an interest in him. In 1942, he was conscripted into the war, serving as a captain, political officer of the 509th Separate Anti-Aircraft Artillery Division, and head of the club. On 15 May 1942, he was captured in Kerch. The Germans subsequently sent him to the Galati concentration camp No. 3 in Romania.

While in Paris, Akaki became close to Mikheil Kedia and the Georgian officer of German intelligence, Givi Gabliani, and became involved in daily emigrant life. He managed to secretly contact Soviet intelligence and started playing a double game.

After France was liberated from Nazi occupation, Akaki began working at the Soviet Consulate in Paris, where he collaborated with Soviet agents sent from Georgia—Ilia Tavadze and Petre Sharia—who were tasked with convincing emigrants to return to their homeland.

In 1946, Ilia Tavadze was summoned to Moscow. Akaki Nizharadze decided to go with Tavadze, despite his father’s pleas not to, as his father believed a difficult fate awaited a former prisoner of war due to Stalin’s and Beria’s brutal policies. Akaki did not listen to his father and went to Moscow, hoping that after “filtration”, he would return to work with Tavadze in Paris. However, as expected, he was not allowed to return. After this, Akaki came to Tbilisi to be with his mother, wife, and child. They had learned from the first wave of emigrants who returned to their homeland that Akaki was alive and living with his father in Paris.

After returning to his homeland, Akaki Nizharadze wrote numerous letters to his father, urging him to return and guaranteeing his safety. He even travelled to Moscow specifically to speak to his father by phone. The experienced 60-year-old intelligence officer Nikoloz Nizharadze understood the situation, but despite knowing the fate that could await him and motivated by the desire to save his son from his dire situation, received permission to return to the USSR in April 1948 and travelled to Moscow.

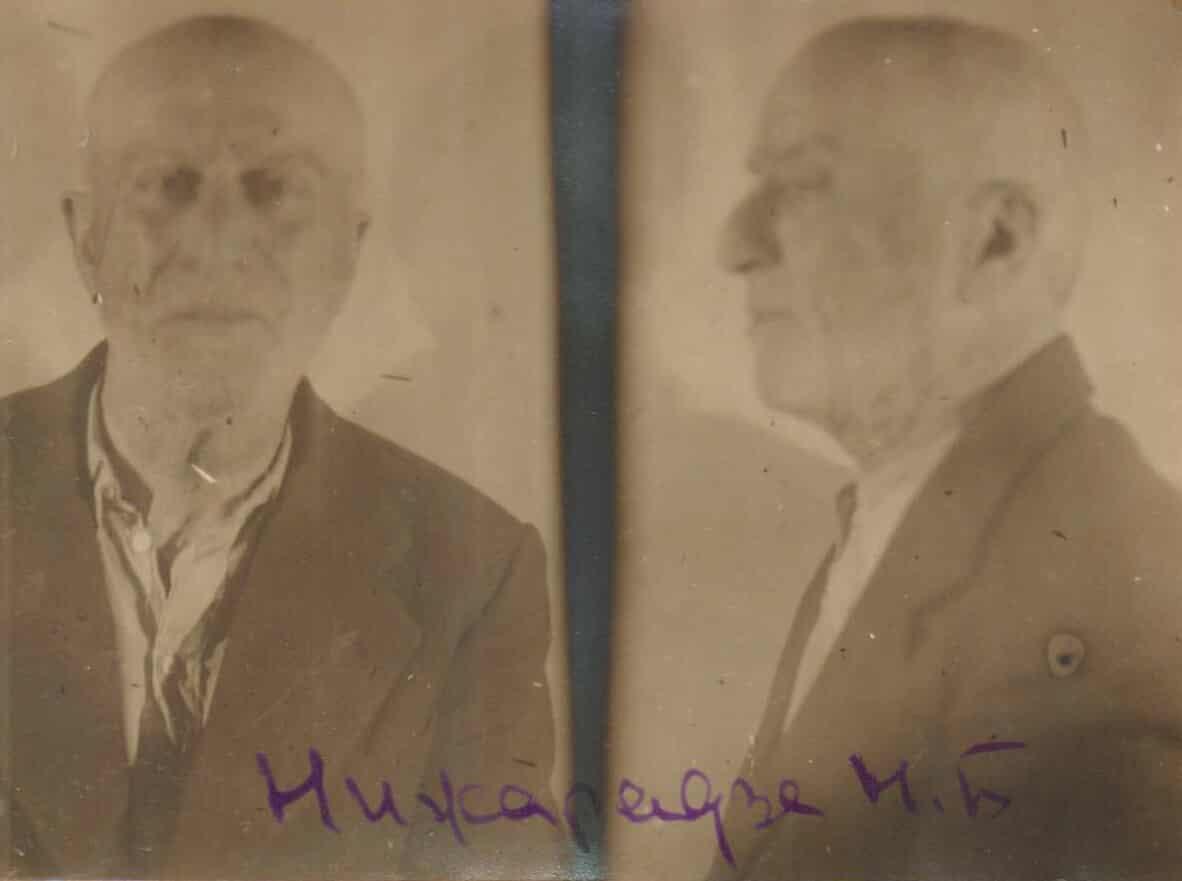

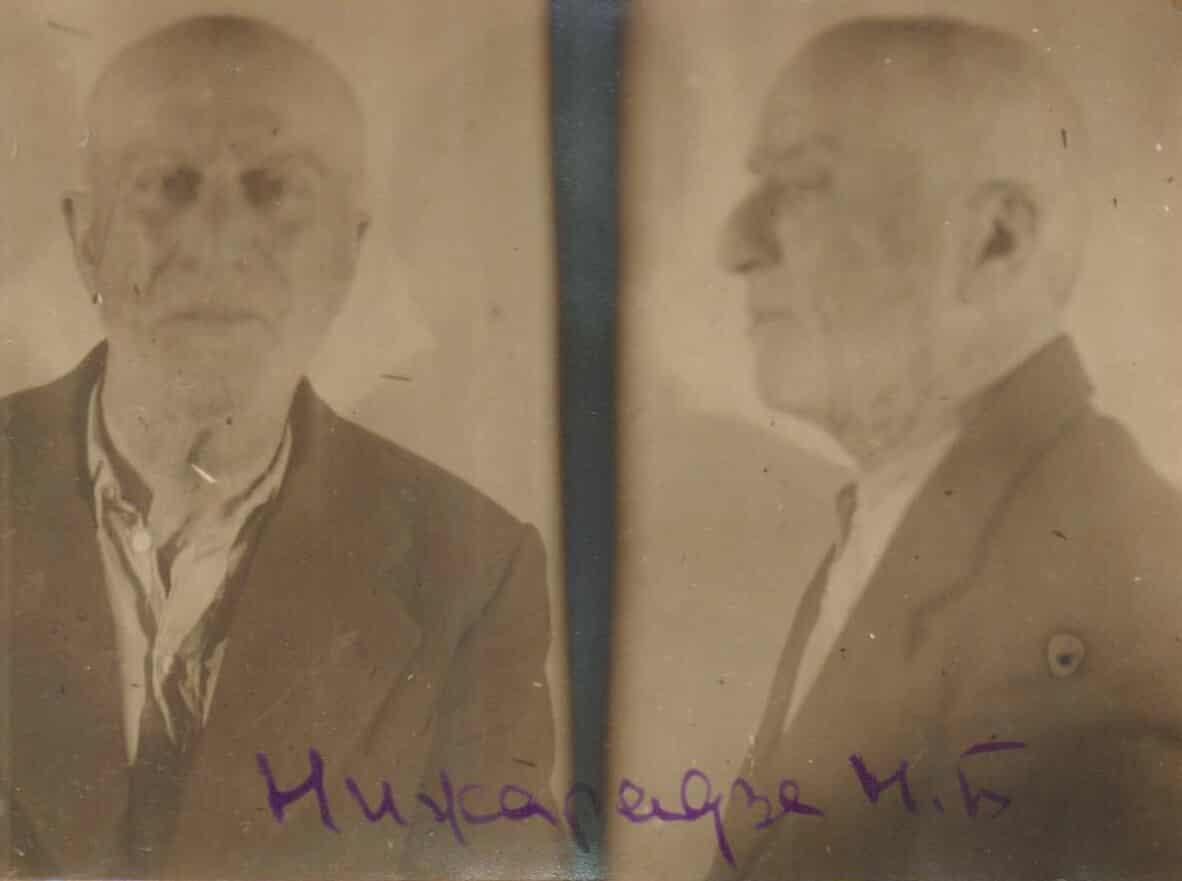

Nikoloz (Kolia) Nizharadze. Photo taken during his arrest on May 1, 1950. Archive of the Academy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (former archive of the State Security Committee)

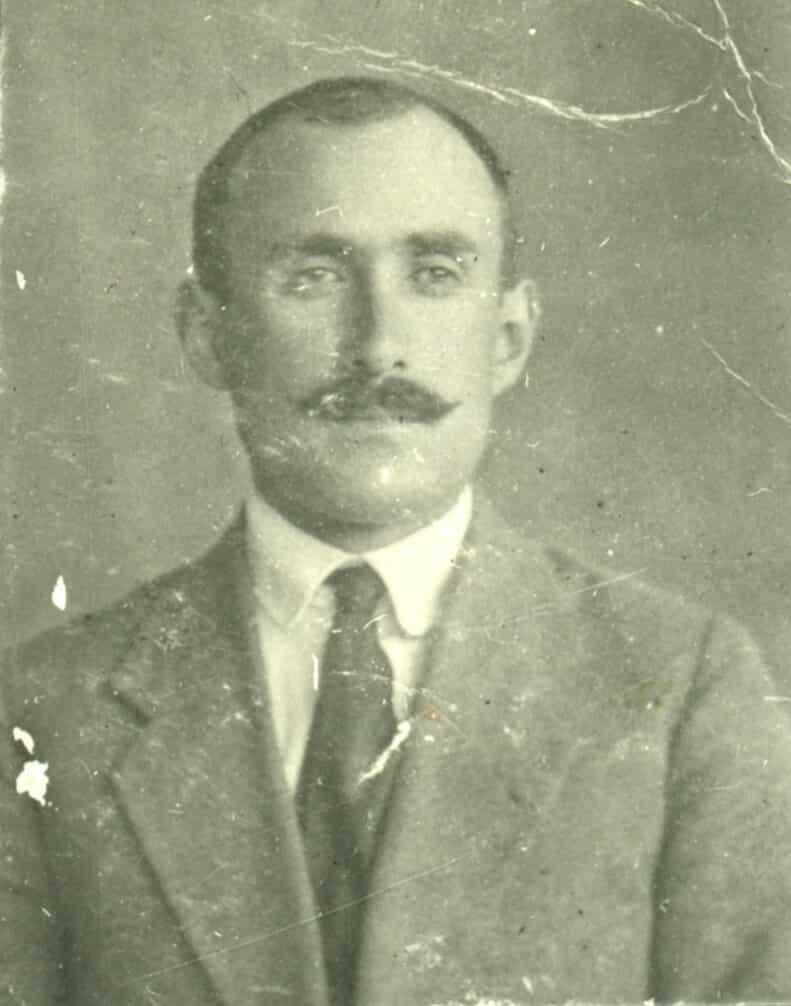

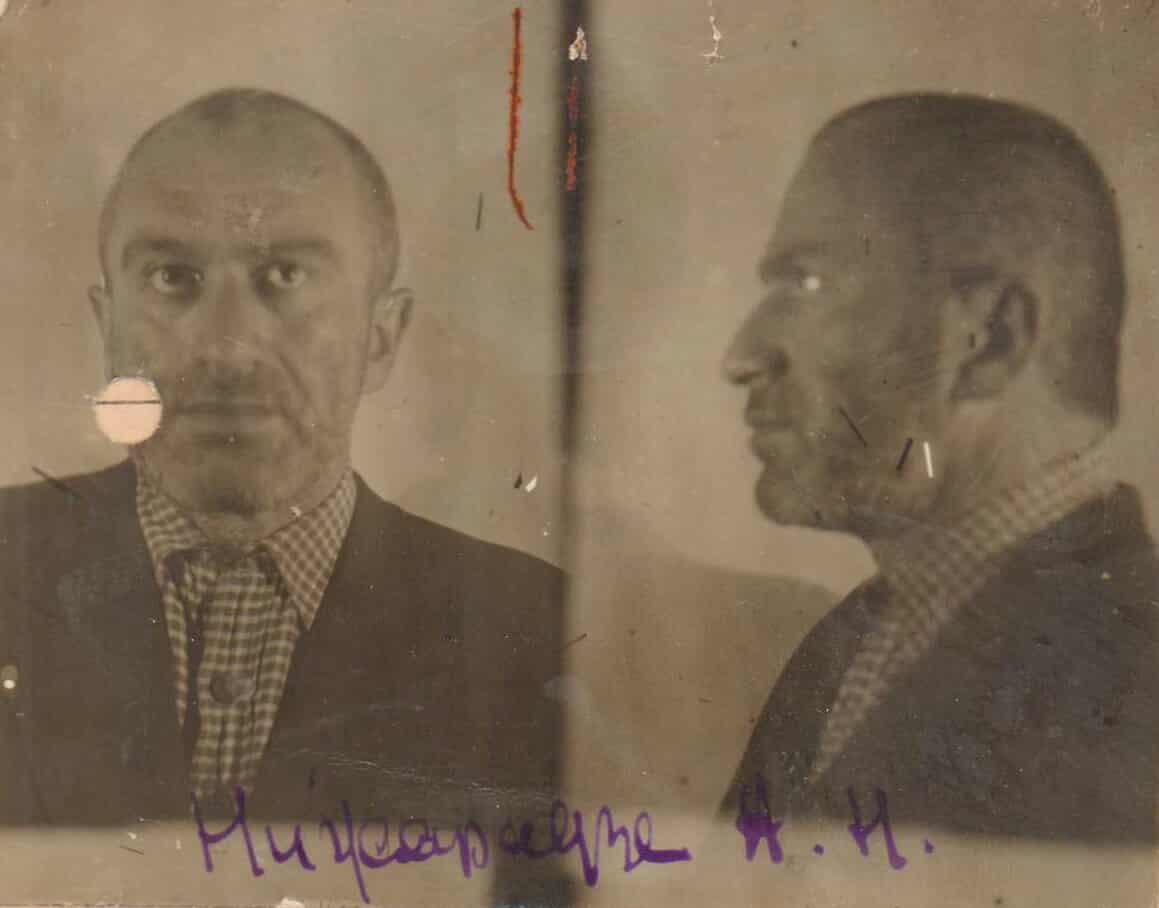

Akaki Nizharadze - photo taken during his arrest in May 1950.

Akaki arrived in Moscow to meet his father. He took Nikoloz to dinner at the Aragvi restaurant, where he introduced him to men who seemed to be employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs but were actually high-ranking Soviet foreign intelligence officials. Gusakov, Natsvlishvili, and Martirosov. The Soviet spies, disguised as diplomats, praised the elderly opponent, who had fought against them for 44 years, for his decision to return to his homeland and give up his anti-Soviet activities. Nikoloz Nizharadze went back to Tbilisi, reunited with his wife, whom he hadn’t seen in 27 years, and started working in his original profession at the city’s pharmaceutical department.

As expected, the Soviet security services constantly monitored the Nizharadze father and son. On January 27, 1950, the head of the Ministry of State Security’s First Department (Intelligence), Colonel Menabde, forced Nikoloz Nizharadze to agree to secret cooperation. He was given the operational pseudonym “Tevzadze” and was soon sent to Batumi to handle a person of operational interest to the security services. Nikoloz Nizharadze did not carry out the Chekists’1 assignment, which led to his arrest on May 1, 1950. His son, Akaki Nizharadze, was also arrested.

Later, on October 9, 1950, Colonel Menabde reported to Nikoloz Rukhadze, the Minister of State Security of the Georgian SSR, with the highest level of secrecy:

‘...after recruitment, “Tevzadze” was directed to cover re-emigrants, including to expose agents of the Menshevik Bureau abroad and foreign intelligence. During his period of collaboration with our agencies, “Tevzadze” provided nothing of interest, despite having very extensive connections among re-emigrants as well as among a part of the Georgian intelligentsia who are of operational interest to our agencies. When he was sent on a special assignment to the city of Batumi to work on a very important target, he got drunk, talked too much, the target became suspicious, and the assignment was foiled. On May 1, 1950, “Tevzadze” was arrested and charged with a criminal offense.”

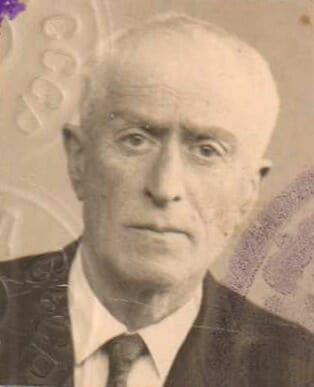

Nikoloz (Kolia) Nizharadze. 1949. Passport photo, which made it possible to identify him at the session of the Constituent Assembly on March 12, 1919.

The interrogation of Nikoloz Nizharadze was personally conducted by Nikoloz Rukhadze, the Minister of State Security of the Georgian SSR, for months. During the interrogation, Rukhadze confronted Nikoloz Nizharadze with his son, Akaki, who asked his father to do everything the Minister of Security demanded of him. Akaki confessed to collaborating with the Germans and also admitted that after the war, he was recruited by Georgian emigrants.

He urged his father to confess everything, which he believed would lighten their sentence. However, Nikoloz Nizharadze denied all accusations. Rukhadze was particularly interested in the exiled head of the Georgian government, Noe Zhordania, his plans, and what tasks he had given to the Nizharadze father and son and other re-emigrants who had returned to their homeland after the war as a result of Soviet agitation. Among them was Polikarpe Rukhadze, the brother of Leo Rukhadze, a member of the People’s Guard’s General Staff, who was arrested along with the Nizharadzes after returning from exile.

Rukhadze kept asking Nikoloz Nizharadze, a prisoner, for information about the connections Noe Zhordania made with the British and Americans after the war. What’s especially interesting is what he said to Nizharadze during his interrogation. It was threatening and he made it clear that he meant to do something about it. “If you think that the Americans... you’re wrong!”

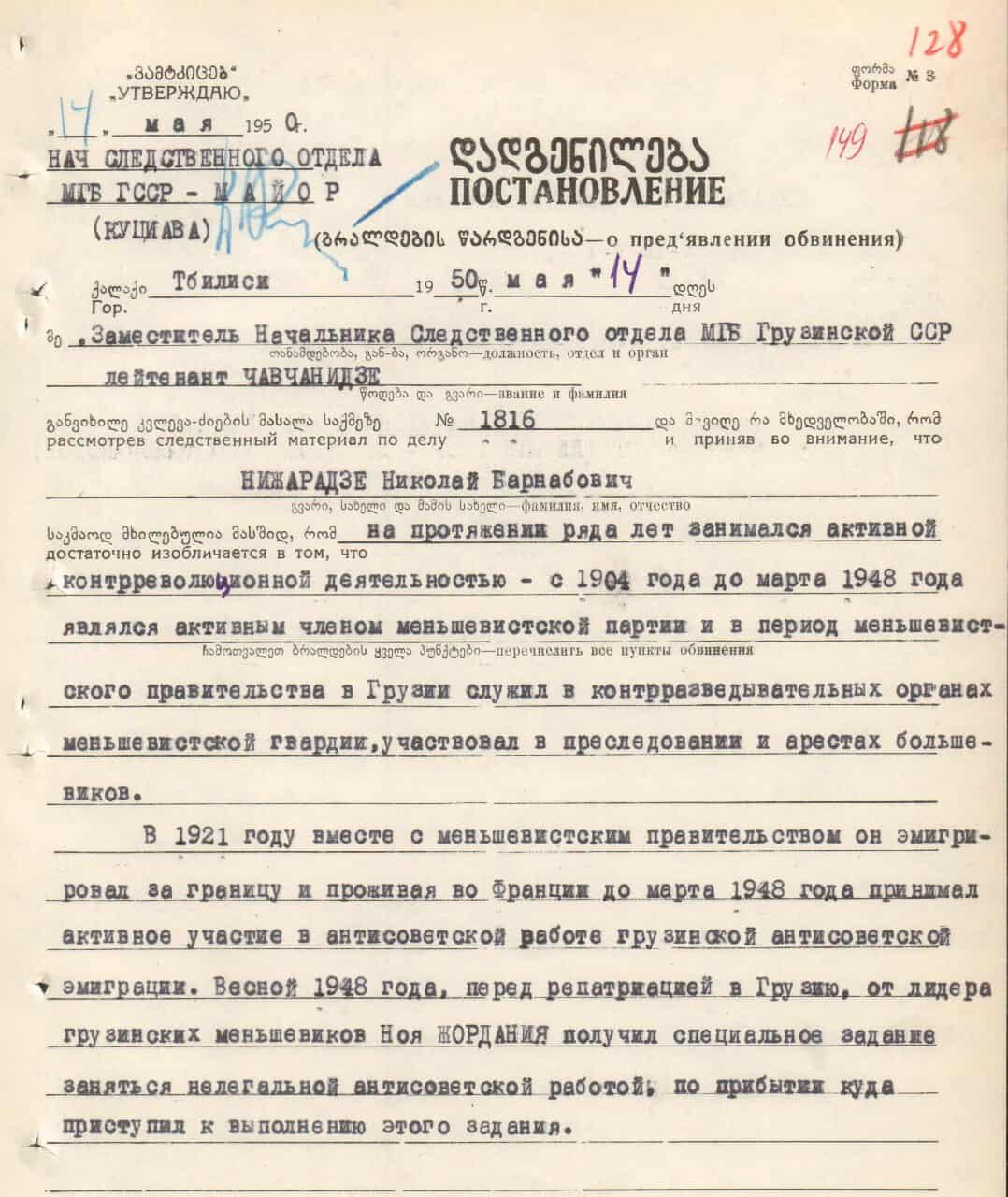

Resolution from the case of Nikoloz Nizharadze. Archive of the Academy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (former archive of the State Security Committee)

After several months of interrogations, psychological pressure, and physical torture, Nikoloz Nizharadze admitted that before legally returning to his homeland, Noe Zhordania had instructed him to campaign about his personality as a national leader and the legitimate representative of the Georgian people, and to convince people that the Democratic Republic of Georgia would soon be restored with the direct assistance of the United States and that Georgia’s legitimate, national government would return.

During the interrogation of Nikoloz Nizharadze by Minister of State Security Rukhadze, it is noteworthy that Rukhadze was primarily interested in the plans of the Americans and Noe Zhordania. He paid little attention to Nizharadze’s past, relying almost entirely on what Nizharadze himself admitted about his ‘service during the Menshevik government’—and even then, only on the most minor details. In Nizharadze’s multi-volume case file, there is no mention of the dispersal of Bolsheviks in Alexander’s Garden, the failed Bolshevik uprising of November 7, 1919, or the Ivanov-Mardaleishvili case.

Nikoloz Rukhadze, who was born in 1905 and began his service in the Chekist agencies in 1927, along with the other Chekists of his generation, possessed almost no detailed information about the secret battles between the Georgian and Russian special services from 1917 to 1921. That generation of Georgian Bolsheviks and Chekists, who were involved in this ruthless struggle themselves, became victims of the Great Terror and mass repressions of the late 1920s and 1937–1938, which completely wiped out all the knowledge and experience of the past.

Throughout the investigation, the Chekists tried to find information about Nizharadze’s past in the state archives, but all they could find was that Nikoloz Nizharadze was listed as a member of the Menshevik Party in 1916. They also found information about a certain Nikoloz Nizharadze, an officer in the Tsarist army, who, of course, had no connection to their prisoner. The Georgian Chekists turned to “the Center”—Moscow—for help. From there, on October 11, 1956, they received a single but very interesting document.

Nikoloz Rukhadze - Minister of Security of the Georgian SSR.

The Second Department (Counterintelligence) of the Committee for State Security (KGB) under the Council of Ministers of the USSR informed its subordinates that the materials of the KGB’s First Main Directorate (Intelligence) contained a copy of an intelligence report (source unknown) that arrived from Warsaw on January 9, 1924, with the following content:

‘...On December 22, 1923, Nikoloz Nizharadze and Giorgi Suladze, with documents issued by the Second Department of the Polish General Staff, left for Georgia via the Sniatyn Station, Bucharest, Constanta and Constantinople to obtain a mobilization plan. The Second Department issued the documents by order of the officer of the French mission in Warsaw, as Nizharadze was registered as his agent. From Constanta, they arrived in Poti on a ship of the Lloyd Trestino company... Upon arrival in Poti, Nizharadze and Suladze went to the Nabada Pier, where ships are loaded with coal. They asked for Milorava at a booth, but the guard told them that he was not there at the moment. After walking a short distance, Nizharadze approached a worker and said, “Adieu, madame,” after which the three of them went to the barracks. There, the whole Poti underground committee, except for one person (whose surname is unknown) who was hiding from the Soviet authorities, were met with fire. The chairman and secretary of the committee are the Milorava brothers. As far as we could tell, the committee has friends on a ship and sends officers and information abroad. Nizharadze said that he and his comrade had come to learn about the plans for the Georgian Naval Commissariat (Tbilisi). He was told that the head of the Naval Commissariat’s mobilisation department had taken the plan back to add something to it. After that, Milorava would bring the plan from him to Poti, along with a comrade who had escaped. The next day, Nizharadze and Suladze went to Kutaisi and stayed at Nizharadze’s brother’s house at 17 Samto Street. There, Nizharadze met his father, and Suladze met his brother.

...

‘Our materials also include a copy of a letter from Salakaia, the chairman of the Georgian Committee in Warsaw, to the Menshevik leader Noe Zhordania in 1924, which partially states: “...Citizen Nizharadze, who was sent to Georgia to obtain a mobilisation plan, received 31 American dollars from us...” We have no other data on Nizharadze’s espionage and intelligence activities or his affiliation with foreign intelligence agencies.

Deputy Head of the Operational Registration Department of the KGB’s First Main Directorate; Lieutenant Colonel Zaitsev

Head of the Second Department; Sokolov”

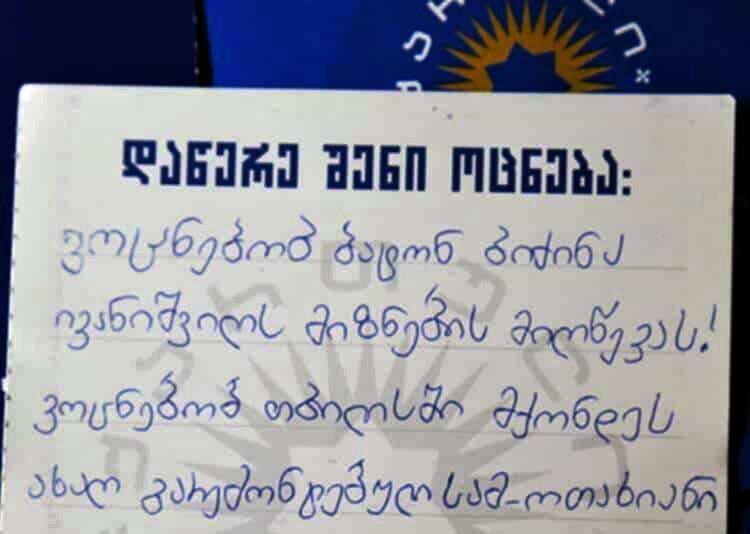

While in the Ortachala prison hospital, weakened by months of physical and psychological pressure, Nikoloz Nizharadze wrote a letter to Joseph Stalin on April 25, 1951, requesting a reduction of his sentence. The letter was written in Georgian, and, of course, it had no effect.

On April 28, 1951, Nikoloz Nizharadze was sentenced to 10 years of prison in Ozerlag (Озерный исправительно-трудовой лагерь, Ozerny Corrective Labor Camp). His sentence emphasized that even after returning from emigration he had not ceased his anti-Soviet activities. His son, Akaki Nizharadze, was also imprisoned.

The multi-volume case file of Nikoloz Nizharadze shows that he was brought back to Tbilisi several times for the review of his appeals. It appears that due to his serious health condition, he was held in the hospital of Ortachala prison during his time in Tbilisi. However, his appeals were rejected by the Transcaucasian Military District Prosecutor’s Office. The last entry in Nikoloz Nizharadze’s case file is dated November 14, 1956, when the Transcaucasian Military District Prosecutor’s Office reviewed and rejected his appeal. Nikoloz Nizharadze died in the camp, and his trail was lost. Unconfirmed information about his death is contained in the aforementioned memoirs of the re-emigrant Porfile Mekhuzla.

In 1954, Nikoloz Nizharadze’s wife, Elizabeth (Vardo) Nizharadze-Chikvaidze, died prematurely from grief over her husband and son. Akaki Nizharadze was released in 1953, after Stalin’s death, and began working at the Radio Committee in Tbilisi. According to some sources, Akaki died in the late 1960s.

Leo Rukhadze, a member of the General Staff of the People’s Guard of the Democratic Republic of Georgia and head of its information and political section, was executed in 1937 after many years in prison and in the camps. He was considered an uncompromising anti-Soviet fighter whom the Chekists found impossible to break or recruit.

Nikoloz Rukhadze, Minister of State Security of the Georgian SSR, was arrested on July 11, 1952. On September 19, 1955, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced him to death by firing squad in Tbilisi. He was executed on November 15, 1955.

Prior to his physical liquidation, the Soviet regime stripped him of his rank of Lieutenant General and all state decorations. He was never rehabilitated during the existence of the Soviet Union.

P.S. The trail of the direct descendants of the Nikoloz and Akaki Nizharadze family is lost after the 1970s. Consequently, we have not yet been able to obtain their family archive and oral histories.

The photographs of the father and son Nizharadze are kept in their criminal case file at the archives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs Academy of Georgia, which is currently closed. By comparing a passport photo issued in 1949 with a famous photograph taken on March 12, 1919, at the opening of the Georgian Constituent Assembly, we assume that a young Nikoloz Nizharadze is sitting in the press box with journalists and representatives of the zemstvo2, wearing a tuxedo and a bow tie.

The details of the adventures of Nikoloz Nizharadze still require much clarification. The forgotten history of an entire generation of his comrades-in-arms awaits the light of day—those who often fought for Georgia’s independence, freedom, democracy, and European future at the cost of their own lives. The Soviet regime erased their faces from our society’s collective memory, and Russian propaganda continues to benefit from the consequences of Georgia’s lost history.

1. Chekist (Rus. chekist, чекист): Originally a member of the Cheka (VChK), the Bolshevik secret police created in December 1917; later used for officers of its Soviet successors (GPU/OGPU, NKVD/NKGB, MGB, KGB), and more broadly for state-security personnel.

2. Zemstvo (Rus. zemstvo, земство): A form of local self-government introduced in the Russian Empire in 1864. Zemstvos were elected district and provincial councils responsible for local economic and social affairs such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, and taxation. They were abolished after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

P. s We would like to thank Valeri Tevdoradze, Merab Chonishvili, and Tamaz Nizharadze for their help in working on Tatia.