Author : Konstantino Jiaquinto

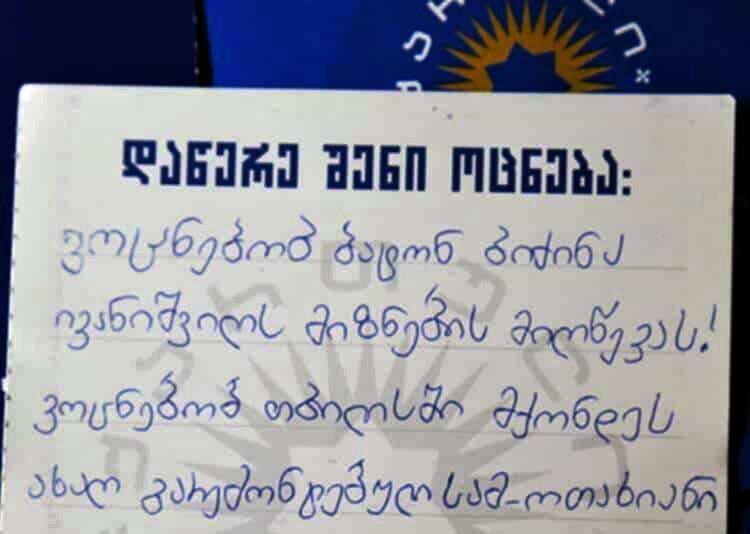

With minor morphological and syntactic modifiers “inclusive” turns into “inkluziuri”, “stakeholders” turns into “steikholderebi”, and “initiation” turns into “dainitsireba”—seemingly Georgian words, but their meanings remain foreign and incomprehensible to most Georgians not belonging to the urban elite or the NGO sector.

Languages are living organisms. They are constantly evolving, borrowing, and adapting. The natural pace of change is typically slow and gradual, with significant changes occurring over three or more generations. Lexical borrowing, which happens because of prolonged contact with a foreign language due to foreign-subjected administration or cultural and trade relations, is part of the natural language evolution process. Ordinarily, about 2 percent of the vocabulary shifts over the course of a century due to language borrowing.

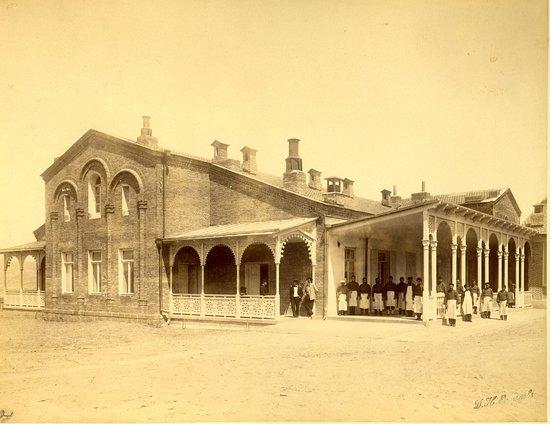

Georgia, a country with a unique language not belonging to any of the major language families, like Indo-European or Semitic, has experienced its share of foreign language influences throughout centuries of foreign conquests and cultural exchanges. Historically, language change due to the borrowing of foreign words has occurred over the span of centuries. Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Russian words have all entered the Georgian vocabulary at significant rates, but their borrowing was gradual.

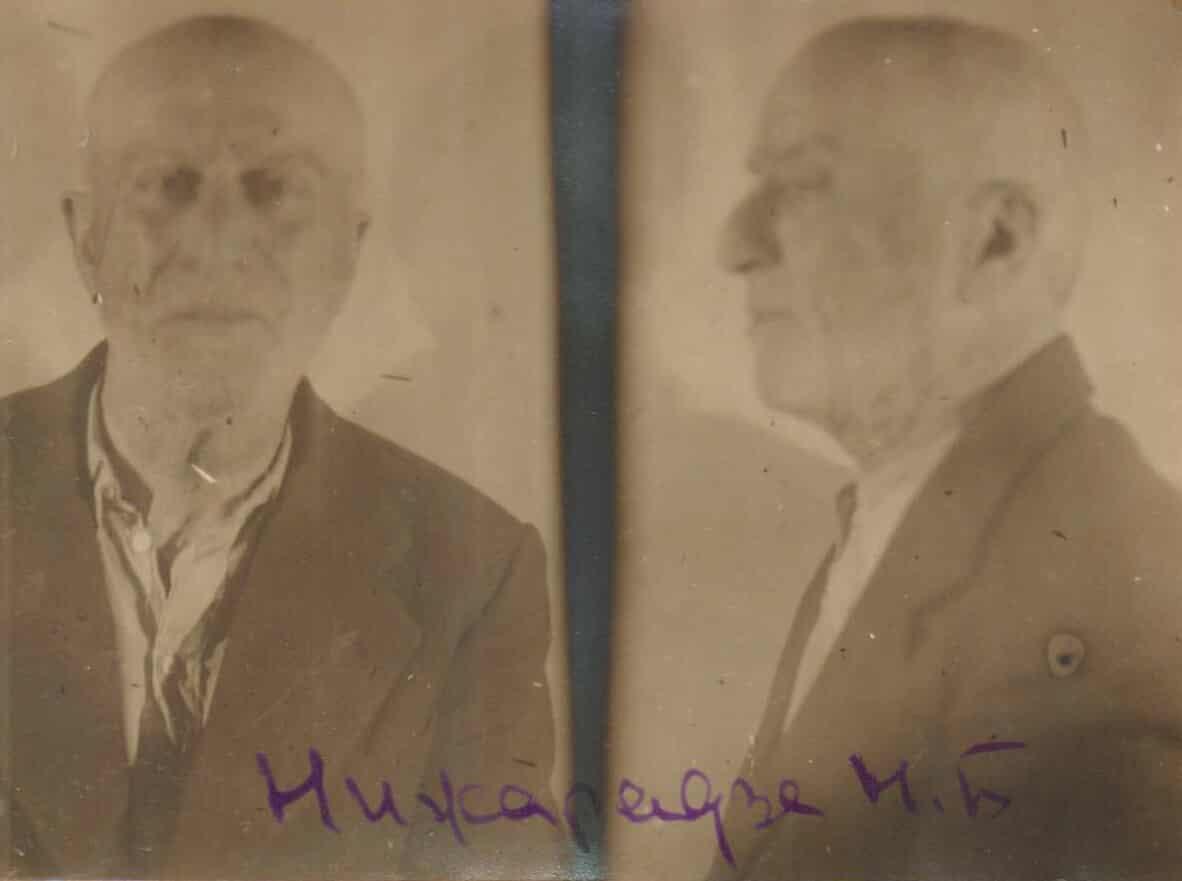

Georgia has navigated waves of foreign influence by a powerful tradition of translation. From Arsen Ikaltoeli’s 11th-century philosophical terminology to Vakhtang VI’s localized adaptations of European and Middle Eastern scientific texts, Georgian scholars acted not as passive conduits, but as cultural mediators. They sought to convey foreign ideas in forms intelligible and meaningful to Georgian audiences, adapting terminology while anchoring it in local epistemological frameworks. This tradition extended through the 19th and 20th centuries, with figures like Arnold Chikobava and Ivane Kaukhchishvili developing technical lexicons and standardizing vocabulary to support Georgian-language science, administration, and education—even under Soviet Russian influence.

However, in the post-Soviet era, Georgia witnessed an unprecedented influx of English loanwords, especially in civic, political, and NGO discourse. While such lexical borrowing can be a sign of openness and modernization, the unchecked and maladapted nature of this process has begun to erode the accessibility of public discourse, deepening social divides.

Since the 1990s, as Georgia has pivoted westward, a new wave of language borrowing has emerged. Some concepts of democracy and the market economy, previously unknown to Georgians, arrived in unfamiliar linguistic packaging, limiting their accessibility and popular comprehension. Unlike the prior period, during which linguistic adaptation was institutionally moderated, today’s inflow of English terms—particularly in the realms of politics, NGO work, and media—occurs in a largely unregulated linguistic space. The terms lacking native equivalents are primarily understood only by urban elites, academics, and those working in the NGO sector.

A massive influx of terms like სეკულარული (secular), იმპლემენტაცია (implementation), ინკლუზიური (inclusive), and გენდერული (gender-based), creates what scholars describe as ‘semantic alienation’ for wide swaths of the population. Field studies suggest that 10–20% of vocabulary in public-facing NGO reports consists of untranslated or semi-transliterated Anglicisms. While this reflects their alignment with global standards and donor expectations, it often distances these organizations from the very populations they intend to serve.

Citizens without Western education, particularly the older generation and rural residents, are increasingly finding the civic language opaque. The result? A language of governance that is unintelligible to much of the governed, weakening civic participation and undermining democratic legitimacy. When terms vital to understanding democracy, rights, or governance are incomprehensible to large groups, it creates a democratic deficit.

Opponents of liberal democracy, such as ultranationalist and populist actors, have seized upon this linguistic disconnect. By framing NGOs and rights advocates as elites who ‘speak the language of foreigners’, they recast technocratic language as evidence of foreign control and cultural erosion. Progressive values—when expressed in borrowed or unfamiliar terms—are easily reframed as foreign impositions rather than organic societal evolutions. For example, instead of ‘gender equality’, populists rally support under slogans like ‘protect family values’; instead of ‘secularism’, they call for a ‘defence of tradition’. These simplified, emotionally resonant terms allow them to present themselves as defenders of Georgian identity against a lexicon they portray as alien and elite.

Democratic backsliding rationalized by ultra-nationalistic ideological narratives is becoming increasingly evident in Georgia by the day. Democratic values are regularly presented as threats to Georgian traditions. Anti-Western rhetoric is no longer propagated solely by openly pro-Russian groups; it has permeated the narratives of government officials and populist talking heads on state-sponsored TV channels. They portray NGOs and civic activists as vehicles of foreign influence.

Many agree that today Georgia is at a crossroads. The country’s pro-Western trajectory and its aspirations for Euro-Atlantic integration enshrined in its constitution are now being seriously threatened. While decades of civil society-building efforts have yielded results as manifested by individual and group activism against the growing authoritarianism, shortcomings of broader civic education work are evident in the dwindling degree of citizens’ unequivocal support for the country’s democratic development. Some parts of the society, especially the older generation and the rural population, appear to be easily influenced by populist ideology. These are the same segments that are particularly prone to alienation from the civic discourse because of comprehension gaps created by the excessive use of foreign-derived vocabulary.

While Georgia’s politics is affected by a myriad of geopolitical factors, forces, and resources at play, ultimately the key determinant of the country’s trajectory will be the attitudes and the will of the Georgian people. Therefore, the democratic discourse must be made accessible and understandable to all segments of the society through a language that is not merely a tool for expression but a foundation of a shared understanding. In this regard, meaningful translation of democratic concepts and terminology adaptation is not just a linguistic task—it is a democratic imperative.