Author : Keti Kurdovanidze

At the end of the 18th century, shortly after the fateful Treaty of Georgievsk came into force, the Georgian man’s dream was somehow based on the Russian narrative, the main characteristics of which were: autocracy, sentimentalism, presenting the past as an idyll, inaction, passive social self-awareness, and the animalistic enjoyment of a simple, stable, and dull everyday life. The Georgian man soon turned this dream into a way of life: he created a conformist’s quiet existence in a society where there is no struggle, no work, no critical thought and debate, where a good horse and a rifle determine human status, learning and education are branded as enemies of happiness, and a book is considered a woman’s job, taking into account the discriminatory context.

I hope you recognize the living environment of the central figure of this era—Luarsab Tatkaridze1. It is a world in which change threatens not only the policies of the conqueror but also the entrenched, almost beastly, daily life of the conquered—those who remain unconsciously loyal to Russian rule. In this context, the dream of a Georgian of that period becomes fully absorbed into the Russian narrative: Russia as master and guarantor of peace, the wealthy and invincible sovereign who will mercilessly hang anyone daring to speak of abolishing serfdom. Even the fantastical tree of diamonds and rubies that Luarsab imagines grows only in the court of the Russian sovereign—guarded by a mighty army, forever beyond the reach of men like him, and therefore attainable only in dreams.

Luarsab thus embodies, in literature, the decline of critical thought under the demeaning embrace of Russian protectorate rule. If Oblomovshchina2 captures the paralysis of the Russian soul, then Tatkaridze is its Georgian counterpart—a reflection of passivity, dependency, and submission to the empire.

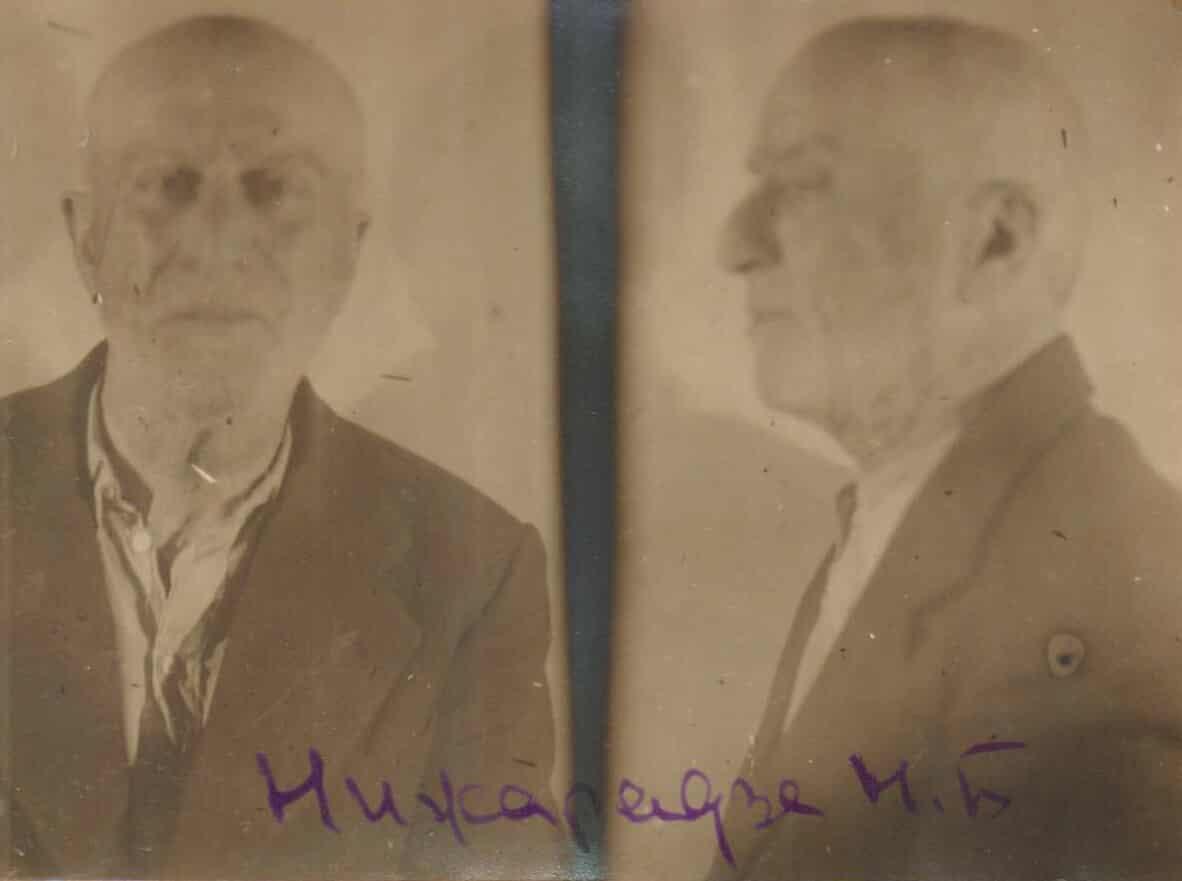

The dream of the Georgian of the Stalinist era is even more closely connected to the Russian narrative, which was conditioned by the revolution, wars, and the sense of collective victory, especially in the Second World War, under Stalin’s leadership. Collectivism, hatred of the intellectual elite and everything different, and the disappearance of individual freedom were connected to the dream of the Georgian of the Stalinist era. The triumph achieved through the Georgian with an imperial identity—’our Soso (Jughashvili)’—was translated into a national victory and still lives on today in Stalinist groups that have turned into a sect.

The destruction and repression of the old intellectual elites led to the emergence of new social strata—the red intelligentsia and the working class. Accordingly, a new dream emerged—for the intelligentsia to receive privileges through loyalty and obedience to the government, and for the working class and peasantry to receive the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, which, on the one hand, would free them from the innate fear and responsibility of independent existence, and on the other hand, would impose a perpetual obligation before the party.

If we look closely, the dreams of Soviet people in general did not differ from the desires of ordinary people, although the scale of these desires was so meager, petty, infantile, and sometimes even humiliating that it left the Soviet people with no chance of being affiliated with the civilised world.

For example, doesn’t everyone dream of a stable and secure life? But what did the average Soviet citizen mean by such a life? Above all: no war, no famine, no shortage of bread or kerosene, and at least some clothes, shoes, and shelter. For the Georgian of the Stalinist era, the nature or quality of these things hardly mattered, because his overriding goal was simple physical survival. This explains why people who had been repressed, scarred by war, and stripped of dignity could still mourn the death of the very leader who had executed their parents, spouses, and loved ones, deported them, or sacrificed them to someone else’s war. More shocking still, for decades many even longed for the return of the Stalinist era, driven by a grotesque belief: ‘After the war, Stalin made everything cheaper. Had he lived longer, everything would have been free.’ Such was the boundless poverty of imagination, born of despair and ignorance. And yet, can we really be surprised that a peasant later believed the promises of a billionaire who, with the help of well-known actors, assured them that every village would receive $5 million?

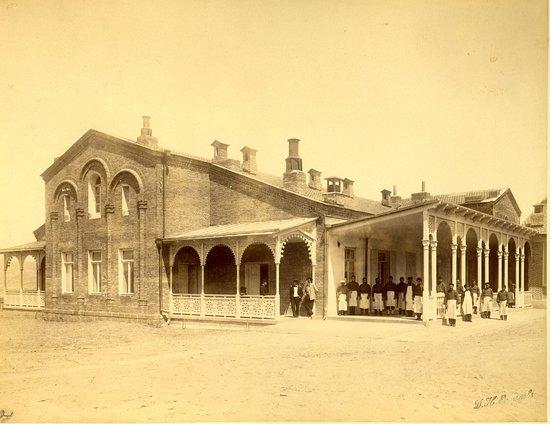

The post-Stalinist era gave way to the so-called ‘stagnation’ period—years of political and social stability, or rather, a stable swamp. To the Georgian’s dream was now added a new mercantile element—‘Soviet happiness’—carefully molded in accordance to the Russian narrative. And what did this happiness consist of? Above all, an apartment that the Georgian worker had waited years to receive. Yet even this reward was not his private property: it belonged to the state, which could evict him at any moment. In truth, it was never a home of one’s own but merely a temporary shelter, granted conditionally and revocable at will.

Soviet architecture reflected the same ethos, manifested in thousands of drab and graceless projects: the Khrushchevkas, Czech, Moscow, Lviv, Kavlashvili blocks, and countless others. Within these cramped shelters, the Soviet citizen arranged and rearranged the objects of his modest dreams, struggling to fit them into narrow, uniform spaces. Later, the advent of cooperative housing introduced the illusion of private space—an ostensible symbol of wealth and freedom. Yet such apartments remained the privilege of the Soviet elite; for the ordinary person, they were not merely unattainable but scarcely imaginable.

For example, owning a car such as a Volga or a Zhiguli was a symbol of success. People would save money for years to join the queue and buy their dream car at the official price. Zaporozhets and Moskvich were the only cars sold without a queue, intended for the working class. Often, the car would become more expensive, meaning that the accumulated money would only be enough for a Moskvich or a Zaporozhets. A proud Georgian wouldn’t even get into one of those as a taxi, let alone park one in his own yard.

For Soviet Georgians, the issue of vacationing was a thorny one. There were elite sanatoriums: Sinopi, the Borjomi Plateau, Litfond, and the Artists’ House in Bichvinta, among others. Only the Soviet elite could afford to holiday here; ordinary mortals and their children had to make do with vouchers for cheap holiday homes with rooms for ten people and pioneer camps. The real dream for complete Soviet happiness was travelling abroad, achievable in socialist countries but unattainable in capitalist ones. Only the elite party nomenklatura and the red intelligentsia travelled to capitalist countries, accompanied by security officials.

Nevertheless, the average Soviet citizen did not lose faith in justice. He sincerely believed that his work would be appreciated, that people would be equal, that he would have a house and a car, that he would be able to travel abroad and that he would be accepted into university without connections or bribery. He believed in this falsehood that was publicised and was waiting for a better future. And so it came: The so-called perestroika or transformation era. The Russian narrative spread the myth that the system could be changed from within, and people believed in Gorbachev’s ‘new thinking’ and the farce of democracy.

The restoration of national identity and the achievement of independence became the dream of the Georgians. However, this could only be achieved through war, bloodshed, and Russian tanks. The overthrow of the first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, and the arrival of Shevardnadze brought the corrupt post-Soviet elite, crime, informal control by the state bodies, nepotism, bribery and economic hardship back to Georgia for ten years. The Russian occupation continued with the de facto loss of Samachablo and Abkhazia. Nevertheless, the dream of the Georgians was to get closer to the West, albeit with a passive approach: ‘Europe, look at us; America, help us; Mother of God, save us.’

Shevardnadze’s position fit the Russian narrative well: A pro-Western policy infused with the rules of the Russian game. The Rose Revolution once and for all separated the post-Soviet symbiosis of these two antinomies and overthrew the myth of two Russias and two Wests, which proved fatal for the Russian regimes in Georgia. Today, when the Ivanishvili regime is trying to restore this Russian narrative and its entire propaganda machine is working on the rehabilitation of the legend of two Russias and two Wests, everyone but the regime’s propagandists and the feeble-minded scoffs at this nonsense.

And yet, from a historical perspective, the Ivanishvili regime adapted to the Russian narrative most successfully, convincing Georgians who dreamed of Western prosperity with almost no effort that the oligarch would use the millions he earned in Russia for the well-being of Georgians; that Russia, unlike the West, ‘will not take away our Georgianness’ and will only limit itself to (!) seizing territories; that the West wants to drag Georgia into a war and is therefore orchestrating a coup against the Ivanishvili regime, which saved the country from war by refusing to join the European Union and saved Georgian men from getting married. Thus, the image of a philanthropist was gradually replaced by that of a peacemaker, who doesn’t need to spend money, bribe the intelligentsia and voters, or get too worked up.

The other day, my nephew recalled the papers that Dream distributed before the 2012 elections, asking voters to write down their dreams. I remember with what enthusiasm and inspiration the Dream supporters wrote down their dreams on these flimsy papers, then took photos and shared them on their personal pages as a given that would surely come true. What a kaleidoscope of dreams they had: apartments, cars, jobs, high salaries, plots of land, tuition funding... There were also more naive and simple dreams, but none of them expresses the economic, mental, and psychological state of our poor people as accurately and meticulously as this card:

Write down your dream.

‘I dream of achieving Mr. Bidzina Ivanishvili’s dream, I dream of having a newly renovated three-room apartment and a car in Tbilisi.’ (The author’s style, spelling, and punctuation are preserved).

I wonder where or how the author of this card is now, is he lying on a couch in Georgia and watching Nadezhda TV, or is he, having survived Mexican adventures, working tirelessly—separated from his family and loved ones—to fulfil his second and third dreams, just like the first one. Oh well, who knows, the ways of the Lord are unfathomable.

This small piece of paper reminded me not only of the misfortune that occurred in my country in 2012 but also prompted me to consider the issue more broadly. It made me consider how the Soviet dream remained in the consciousness of the post-Soviet person and how it became the political programme of the so-called Georgian Dream. The Georgian Dream, as both a political force and a cultural phenomenon, seems to be a natural continuation of this unformed post-Soviet mindset. Consequently, we have a state in which citizens fear change and progress, preferring to live under the protection of a powerful patron despite the violence, injustice, repression, and economic hardship they endure at his hands.

Today, in this time of trial, we must understand that neither independence, nor integration into the European Union, nor democracy can be a guarantor of freedom, because freedom begins where dreaming no longer means relying on others, inaction, fear, and conformism. And so, as long as this dream exists, the country is not destined for development, and people are not destined for peace and well-being.

1. Luarsab Tatkaridze: A fictional character created by the Georgian writer Ilia Chavchavadze in his satirical story ‘Is That a Man?!’ ( 1858-1863). Tatkaridze symbolizes the passive, ignorant Georgian noble loyal to Russian rule, embodying stagnation, dependence, and the decline of national consciousness.

2. Oblomovshchina: A term derived from the protagonist Ilya Oblomov in Ivan Goncharov’s novel Oblomov (1859), denoting apathy, inertia, and social stagnation. It came to symbolize the broader cultural and moral paralysis of the Russian gentry in the 19th century.