Author : David Bukhrikidze

Indeed, theatre has always been a political, social, and contemporary art form—from Greek tragedy to Molière’s itinerant troupe, Shakespeare’s Globe, and French classical drama. In the twentieth century, theatre became even more incisive, political, and relevant as the works of Bertolt Brecht, Antonin Artaud, and Samuel Beckett radically transformed its language, meaning, and message.

The humanitarian crisis after the Second World War made the existence of a bold and experimental form of theatre even more relevant. This demand was based on overcoming the classical textual framework and getting closer to the people, talking about intense and concrete stories and empathy. It is somewhat paradoxical that such a theatre was born in America after the wars and traumas that Europe had gone through.

We are a group of actors striving to spark a non-violent and beautiful anarchist revolution… The audience responds: Yes, the world is in turmoil! Wars rage on, political and social conflicts persist and disasters unfold everywhere. But who am I? Where do we stand? And what can we do to change the world? It is precisely to awaken this understanding and empower people that we create Living Theatre…

This is a fragment from the manifesto of Judith Malina, an actress, writer and director born in Germany to a Polish Jewish family and a student of the renowned Erwin Piscator. Together with her husband, the American artist and performer Julian Beck, she founded a radical political theatre company, The Living Theatre, in New York in the 1950s.

This was a completely new direction in theatre that moved away from traditional buildings and into different spaces: bus stops, abandoned buildings, squares and public gardens. Julian Beck and Judith Malina wrote texts that corresponded to the political and social reality and tried to revive public and social impulses through this form. Indeed, in the early 50s, The Living Theatre became one of the most distinctive and experimental theatres, and not just in the United States.

By its very nature and concept, The Living Theatre aimed to transform the organization of power within society. The destruction of the hierarchical system and the establishment of horizontal relationships with the audience by provoking their own problems was one of the main ideas of The Living Theatre. Beck and Malina’s troupe was clearly opposed to the commercial nature of Broadway shows. Given the location, they staged performances with social, expressionist or political content and were constantly involved in demonstrations and protests in New York.

Georgian theatre had little experience of anything like The Living Theatre. Cemented in the Soviet system for decades, it remained confined to performing the works of Shakespeare, Molière and Kldishvili within a rigid, nomenklatura-approved framework.

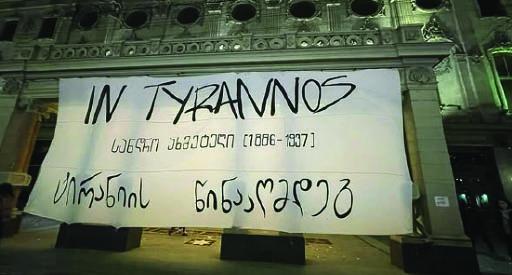

So, when the musical “I Will Swim Across the Sea”, directed by David Doiashvili, who originally staged it at the New Theatre in 2023, was performed in the streets outside the theatre during the January protests, the audience witnessed not just a performance, but a modernized fusion of protest manifesto and theatrical expression.

It was a performance inspired by clear political messages, impressive civic stance and social theatre. Irakli Charkviani’s music and lyrics, which form the basis of Basa Janikashvili’s dramaturgy and Davit Doiashvili’s directorial accents, take on a completely new, lively and political resonance. It can be said that the New Theatre that took to the streets, with its boldness and specific messages, was very similar to the social and political statement of Julian Beck and Judith Malina’s The Living Theatre.

The social and political events taking place in the country, in particular the arrest of the members of the theatre troupe as well as Andro Chichinadze, forced the actors to leave the building and resort to a form of protest.

Propaganda media and trolls have spread false claims that the New Theatre was renovated by Cartu Foundation. In reality, the renovation was funded by the Ministry of Culture’s budget—that is, by our taxes. Therefore, any discussion of Ivanishvili’s so-called charity is irrelevant. Moreover, the funds the Cartu Foundation spent on the rehabilitation and repair of various theaters have long been reimbursed through various means.

The project to renovate the New Theatre was approved during the time of former minister Mikheil Giorgadze. However, the honor of inaugurating the renovated theatre fell to Tea Tsulukiani, who never visited it again. The invisible tension between the Ministry and the New Theatre was always felt during Tsulukiani’s time, and after the adoption of the Russian Law and the ensuing protests, this tension became undeniable and fully exposed.

“We are launching the manifesto of the New Theatre! This has been our fight, but friends, other theaters and actors will surely join us. And I’m announcing that the New Theater is heading to the regions! We will go everywhere, speak to everyone, expand across different areas, and then go and try to chase Georgian theater!”

This loud and passionate declaration by the theater’s artistic director, David Doiashvili, seemed to serve as a direct signal for the government’s troll factory to spring into action. In a coordinated attack, they unleashed a wave of insults and abuse against the theater’s actors and director—as if they weren’t the same people who had been begging for a couple of tickets just a few months before.

As part of the “Protest Manifesto”, performances were held in Batumi, Zugdidi, Kutaisi, Ozurgeti... The improvised musical, performed in the open air, was attended by many people, although the government’s mobilization was also considerable. But the most moving part was the letter written by Mzia Amaglobeli from prison, read on stage by her relative, a young girl... The uplifting refrain of the actors, dressed in colorful cloaks and warm clothes, of “I will swim across the sea!” was delivered like an electric current to the audience of both old and new generations. The artistic and musical energy of the performers seems to force us to look anew at The Living Theatre as an expression of impressive, sincere protest.

Energetic movements and gestures, slightly tired but unbroken voices come together in the finale with the main message: “Freedom to Andro Chichinadze! Freedom to the prisoners of the regime!” which sounds even more impressive against the backdrop of total political madness and police violence police.

It is symbolic that the musical “I Will Swim Across the Sea” is a kind of summary of Irakli Charkviani’s music, and today it sounds in the streets, on the squares; it sounds bold, on the protest stage, and alive... It would be an irony of fate if the ghost of Irakli’s grandfather, Kandid Charkviani, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Soviet Georgia in the 1950s, would appear mockingly as the Commander to the oligarch of the Georgian Dream government and lead him exemplarily to where “no traveler has returned from” (don’t think anything bad, it’s just a quote from “Hamlet”).

The musical is also interesting in that it accurately reflects the signs of Soviet Georgia in the 1980s, that is the era of “stagnation” (“Zastoi”). It is noteworthy that the performance begins with a reference to a specific time, the preparations for the parade of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, and also ends at a specific time, 1989, the period of the awakening and manifestations of the national movement.

In David Doiashvili’s interpretation, the main characters of the musical do not so much carry the signs of the “stagnation” period of Soviet Georgia, but rather the protesting gaze of today’s youth with their personal dramas and problems. Irakli Charkviani’s music and Ketato Popiashvili’s compositions seem to be the main accelerator of this “stagnation”, a kind of aesthetic catalyst of the past time, which includes about twenty musical pieces and songs and, moreover, dictates the main plot lines to the director and playwright.

Strange as it may seem, The Living Theatre has been recreated after nearly 70 years depicting events in Georgia much more eloquently and correctly than works of Brecht and Shakespeare, which were deemed dissident at the Rustaveli Theatre, since converted into a museum space. Because the accumulated fear of past generations has turned into a reactionary social swamp there, and “fear eats the soul” (this is the title of a film by the great German director Rainer-Werner Fassbinder).

Fortunately, the protest manifesto of the New Theatre and the new generation no longer acknowledges fear, because a return to the past is impossible and unacceptable. The Living Theatre not only breaks the boundary between conformism and rebellion in our imagination, but also concretely points to the crisis and death of the system... Andro Chichinadze and many other artists, painters and writers are still in prison. And the New Theatre is still on the streets, trying to encourage the prisoners of the regime with live performances and to finally free them...

We shall swim across the sea, and fear shall no longer eat our souls.