Author : Timothy Blauvelt

The concept of a national archive that preserves the records of a state for the benefit of society is a relatively modern one. With the evolution of bureaucracies as institutions of state administration, records were preserved and accumulated at first for administrative use by the state’s bureaucrats. The first national archive was created during the French Revolution by the National Assembly shortly after the storming of the Bastille, and the concept of institutionalizing the preservation of at least a portion of state documents for the use of the public and of future historians spread around Europe in the course of the 19th century. Together with concepts of constitutionalism, democratic governance, the rule of law, and freedom of belief and expression, the state archives represented a public space in which memory and knowledge could be directly shared between the government and the governed. In the words of Canada’s Keeper of Public Records, Sir Arthur Doughty, in 1924, “Of all national assets, archives are the most precious, they are the gifts of one generation to another, and the extent of our care for them marks the extent of our civilization.”

For the same reasons of “knowledge is power,” 20th century authoritarian and totalitarian states severely restricted access to their archives and purposefully manipulated the historical record. As O’Brien tells Winston Smith during the latter’s interrogation in Orwell’s 1984, “We, the Party, control all records, and we control all memories. Then we control the past, do we not?” Hence the Party slogan, perhaps the most famous line in the book: “Those who control the present, control the past and those who control the past control the future.” This was nowhere more thoroughly reflected in practice than in the Soviet project, where the official archives were created by a decree of Lenin on 1 June 1918. The Bolsheviks, perceiving themselves as reshaping history, documented their activities meticulously. Yet they viewed their archives as repositories for the exclusive benefit of the party and the state apparatus, protecting this valuable knowledge from the public and controlling its interpretation.

With Gorbachev’s new “openness” under perestroika and glasnost’ and then the fall of the Berlin Wall and ultimately the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, one of the most remarkable aspects of the post-Cold War “wave of democratization” was the opening of the state, party and secret police archives in many of the newly democratizing states of Eastern Europe, and to some degree in the newly independent republics of the former USSR. The “End of History” seemed to inherently involve a return of history. Yet despite the aspirations of the archival goldrush of the 1990s, when the major state and party archives in Moscow and St. Petersburg threw open their doors to researchers and began publishing (and, in some cases, selling) their catalogues, the new archival opening in the post-Soviet space was in many ways not only ephemeral, but also uneven and partial. The most complete archival opening took place in the Baltic states, where today the degree of access and transparency rivals that of any western European or North American country. Most Central Asian republics never deemed to open their archives at all, or at best opened them only slightly. Some major central historical archives in Russia remained closed to researchers, such as those of the Soviet military and the secret police. And even before access started to again become restricted with the return to authoritarianism in the Putin era, the mentality of most of the archivists remained fixed in the old Soviet mold, viewing their role as one of protecting the documents – and hence, knowledge of the past – from the people, rather than of facilitating researchers’ and the public’s access.

During the later 2000s and into the 2010s, other independent states of the former Soviet periphery became the new epicenters of archival openness, such as Armenia, Moldova, and especially Ukraine briefly following the Orange Revolution of 2004-5, and then more conclusively after the Euromaidan of 2013-14. The Ukrainian Institute of National Memory was created as a non-political public entity for archival preservation, and the fully opened archives of the Ukrainian KGB (Haluzevyi derzhavnyi arkhiv Sluzhba Bezpeky Ukrainy, known as the SBU Archive) became a major resource for understanding the Soviet secret police and the functioning of the system as a whole. Even during the current war, although the main SBU Archive reading room in Kyiv is closed to researchers because it is a military target, they send scans of any documents requested to researchers anywhere in the world for free. Ukrainian archivists have also made heroic efforts to preserve their archives from Russian aggression and to relocate those from the regions under Russian occupation.

After the Rose Revolution, Georgia showed signs of becoming a model of archival openness in the region. The Georgian National Archives are under the Ministry of Justice and comprised of the Historical Archive holding the records of state institutions, most notably of the Tsarist regime and of the 1918-21 Democratic Republic, and the Contemporary History Archive which holds the state (commissariats and ministries) records of the Soviet period. They were simple and straightforward. In my experience over a number of years, within 10 minutes of delivering the application letter I was already working in the reading room, requested files were delivered the same day, and there were no restrictions on what files could be viewed. By a presidential resolution in 2007 the massive archive of the former Georgian communist party was formally opened to the public and relocated from the basement of the IMEL building, where it had been deteriorating, to a newer facility in a telephone exchange building in Mukhiani. New boxes for the files were provided, and restoration work was undertaken on damaged materials, with the help of experts from the National Archives. By the same decree, the archive of the former Georgian KGB was made accessible to the public, though these remained stored in the Interior Ministry “Moduli” building and were then transferred to the Police Academy. Both the party and KGB materials were organizationally consolidated under the Archival Administration of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Resources were provided for their conservation, and also for their public dissemination. Under the inspired leadership of Col. Omar Tushurashvili, the Archival Administration sought to bring public attention to these national treasures, through issuing the journal arkivis moambe / The Archival Bulletin and other publications in Georgian and English, producing documentary films, organizing programs for high school pupils and university students and welcoming local and foreign researchers.

Even during this “golden period” of archival openness in Georgia, there was still considerable areas for improvement, especially compared to the Baltic countries. The majority of the Georgian KGB archive was destroyed by fire in the course of the conflict in Tbilisi in 1991-92. The official tally was that only approximately 20% remained. And according to the official line, all of the informant files were destroyed in the fire, leaving behind mostly criminal case files. Although lustration laws were passed in Georgia as they had been in other former socialist countries, this had little impact on society as the general consensus was that all the informant files and card indexes had been destroyed. Never mind that fire is rarely so selective and that the KGB likely had similar dossiers stored in its offices in other parts of the country. In all of the state archives – the National Archives under the Justice Ministry and the party and KGB archives under the Interior Ministry – photography and scanning of documents with one’s own equipment, something that in most western archives is allowed and free as long as regulations are followed and ownership rights observed, remained forbidden and/or prohibitively expensive, especially for local researchers and students. The passage of laws restricting access to personal data in archives less than 75 years old threatened to obstruct research on more recent history, although these were not applied consistently.

Despite these issues, however, for a number of years Georgia truly was something of a beacon of archival openness in the region, and the period was one of a particular flourishing of research on the history of Georgia and the Caucasus by both local and foreign scholars. Then things began to change in the National Archives, with a reversion to Soviet-style access procedures requiring a 10-day processing of a researcher’s request for access (though in practice this often extended for weeks and months), a two-day waiting period before ordered files could be provided and a restriction on the number of files that a researcher could request. More ominously, according to reports of former employees, requests for access by foreign researchers had to be forwarded to the Ministry of Justice for informal review and approval or rejection. An increasing number of such foreign researchers were denied access, although never directly: they were told instead that the National Archives did not possess the materials relevant to the researcher’s topic. This was the case even if other scholars had already used such documents. They might also be told the relevant materials were unavailable because of restoration or digitization, including in some cases where the researcher did not indicate specifically what files they wanted to use. In some cases, it was known that these materials had even already been digitized. In one particularly egregious case, a document that a researcher was told was unavailable in any form turned out to have been already posted for several years on the archive’s website. Often foreign scholars’ request letters were reported to be “lost” when they arrived in the country to start their research, and in some such cases the eventual appro¬val (entirely coincidentally) came just in time for their scheduled departure from the country.

In addition, researchers recently photo¬graphed a list held behind the reading room attendant’s desk of the Historical Archive that were apparently off limits to foreign researchers, including some of the major collections related to the Tsarist administration of the Caucasus. Recently as well the period of validity of approval for researchers to use the National Archives was changed from the end of the calendar year (thus permission granted from the start of January would be good until the end of December) to just three months, giving the administration more frequent opportunities to deny access. In some cases, researchers applying for renewal of permission were told the materials they had been using just the previous day were now unavailable. There was no clearly discernable logic about who was to receive such treatment and why, though it may have related to topics that are potentially politically controversial in Georgia, such as Islam and state borders, and scholars from Turkey seemed particularly likely to receive de facto refusals (though this has happened as well to American, Russian and German scholars).

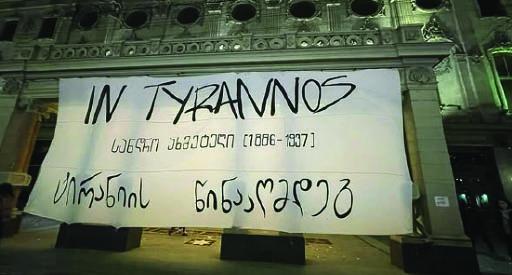

Until recently, and somewhat paradoxically, access to the Georgian party and KGB archives under the Ministry of Internal Affairs had remained open and unobstructed. Application letters had been approved rapidly, usually on the same day, and files were brought within minutes of ordering them. In my own experience, I was never refused access to any file that I requested. All of the inventories for the major fonds (finding aids that list the titles of the individual files) were available in PDF form on the Archival Administration website, a great boon to researchers allowing them to save a great deal of time in preparatory work before arriving at the archive. However, in 2021 the Archival Administration website was taken down for reconstruction, and remains offline today. Then in late 2023 both the party and KGB archives were suddenly closed to the public. Vague explanations were proffered related to the security of the website and a supposed “re-inventorization” and about potential plans to unify these archives with the National Archives. Even the archives’ staff seem perplexed as to the reasons for the closure and unable to speculate as to when and how they might reopen. Publications and other activities of the Archival Administration have nearly ceased, and several grant projects of international donors that would have assisted them in publications, restoration and digitization were blocked and apparently cancelled.

Thus, at the current moment in early 2025, access to the National Archives remains precarious, especially for foreign scholars, and the former Georgian party and KGB archives – major resources for the study of 20th century Georgian history – are entirely inaccessible to the public. Appeals from local and international scholars, non-governmental organizations and foreign embassies have fallen on deaf ears. Foreign researchers have had to cancel long-planned research trips, and some of my Georgian MA students have had to postpone their thesis projects. One can only speculate as to the precise motivation behind these obstructions to access and at what level such decisions are taken. History and, it seems, particularly the Soviet past, seem to be considered dangerous by somebody somewhere in a decision-making position.

Compared with things like the falsification of elections, unconstitutional restrictions on freedoms of speech and assembly, and extrajudicial detentions and punishments, hurdles to archival access might seem relatively mild. And yet they are a subtle yet powerful indicator, a canary in the coal mine. In the words of the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, “Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation.” Recently in Georgia there has been much discussion lamenting the fact that despite all of the efforts at state reform over the past 30 years, the judicial and internal security structures have remained politicized pillars of the ruling party. The direct subordination of the main Georgian archives to the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Internal Affairs – despite the continuing and well-intentioned commitment of the archivists and the administrative staffs of these archives – has meant that they remain vulnerable to the political vicissitudes of whoever is in power. As with the state structure as a whole, a non-political and independent agency or institution for the archives is essential in the future in order for them to fully serve their potential role as a public space in which memory and knowledge can be directly shared between the government and the governed in a functioning democracy.