Author : Keti Kurdovanidze

“At a time when the entire Republic of Georgia has been turned into a prison, it is easy to imagine what the prison itself, set up within this larger prison, will be like. Almost 80% cannot be charged—what could they possibly be charged with? Under these conditions, political prisoners are treated more harshly than criminals. Not only does the administration not meet any reasonable demands within its capabilities, but it deliberately provokes us because it is rewarded for oppressing political prisoners. The prison administration is assisted by up to 150 communists imprisoned for different crimes. These thieves, bribers and bandits are trying to make up for their dark past by denouncing and informing. From this description you can easily imagine our situation.”

This is an extract from a letter written by a political prisoner from Metekhi prison in 1921. And yet how shockingly modern it sounds today, when Georgia’s prisons are full of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience...

It all began in 2012, when the Georgian Dream party came to power through a Russian special operation. At that time, many could not even imagine that inspired by the hope of a better future, they would soon have to fight against repression, violence, unheard-of corruption, shifts in the country’s Western orientation and Russian dictatorship, and that because of this they would face persecution, violence, dismissal from work and even imprisonment. They didn’t foresee it when the leaders of the former government, who had gone over to the opposition, were imprisoned; when the third president of Georgia was put on trial for buying jackets and soap; when young people’s eyes were gouged out on Gavrilov’s night; when the Russian law was supposedly withdrawn forever.

And yet this society has always claimed to be literate, educated, progressive and educated in humanitarian values. This is what happens when, for many, these values are not organic but formal, due to a lack of critical thinking and deep self-awareness. What kind of result can come from an education system that is focused solely on memorizing facts, rather than on analysis, solving moral dilemmas, or developing social skills? On top of that, there is a lack of individual responsibility, meaning that people often base their decisions on group conformity or populist narratives. This is why the humanism in our society is so fragile and false, rather than universal and genuine. The situation created in Georgia today is so obvious that many of these people have distanced themselves from the Russian regime. However, the vast majority of them refuse to acknowledge their role in bringing about this regime. Moreover, like Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, they try to justify their fatal mistake, believing that by supporting the Russian regime they were fighting for democracy and a better future. Raskolnikov himself thinks this way; in his eyes, the pawnbroker woman is a useless member of society, and her death can be justified if it serves a “great cause”.

With this motive, a significant part of our society became involved in the existential “process” that Putin’s Russia initiated against Georgia through Georgian collaborators. Indeed, we found ourselves in the reality of Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial: we are being arrested without knowing why, accused without understanding what for. And when there is no crime, there are no arguments to refute the accusation. This is the very absurdity of Kafka’s justice and the court—an invincible weapon in the hands of the system. And this justice is very similar to the Russian justice established in Georgia, which has long gone beyond the institutional framework and, one might say, even beyond the borders of the country, because today trials in Georgia are conducted by sanctioned judges, who also carry out the orders of an oligarch sanctioned for cooperating with Russia, and the oligarch, in turn, carries out the orders of a dictator recognized as a war criminal by the Hague Tribunal. It is precisely this kind of labyrinth that now holds captive all those awaiting their sentences in or outside the cells, because under the Russian regime “deprivation of liberty” as a legal concept and the prison as a penal institution have lost their institutional meaning and taken on an existential character.

Was it really so difficult for our educated society to realize that an Orwellian dystopian reality awaits us? On the one hand, Orwell’s popularity among Georgian youth far exceeds that of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin”, but on the other hand, the oligarch’s admiration for Orwellian totalitarian rule had been openly declared from the very beginning, without any metaphorical hints. And yet, what was so unbelievable? That he wouldn’t dare, wouldn’t let himself, or did the people really believe that if they didn’t like him they would vote him out? No, of course not. Almost everyone knew in advance who was coming to power, but they thought it wouldn’t affect them, that the pension the oligarch gave them would be permanent, that as supporters of the Georgian Dream they would have every right, while the restrictions and persecutions would apply only to members of the National Movement.

This is what happened in the first stage, but to establish a dictatorship it is not enough to discriminate against opposition parties; total censorship and the elimination of anything different, the destruction of potentially threatening factors to the regime and total obedience are required.

As for the young, they could not even imagine that the National Movement, vilified by Russian propaganda, and the demonized third president were being unjustly and illegally persecuted. They sincerely believed the fabricated stories of 26,000 raped men, the president’s wife trafficking in human organs, a man-eating wolf chained to the balcony of the law enforcement minister, Abkhazia “handed over” by the former government, and “sleeping Tskhinvali” awakened by the roar of Georgian machine guns in 2008. They believed it because no one had ever explained to them what happened in 1991-1992, what kind of country the government inherited after the Rose Revolution, what challenges it faced, what mistakes the reformers made, and why they paid such a bitter price. Some heard these myths at home, others among their friends, and the “opposition to the opposition” began to reinforce these compromising narratives, and it even made them trendy—“supporting the National Movement and Saakashvili was considered ‘mauvais ton’”.

We have arrived at this point under this paradigm, and despite veering off the Western course, establishing a Russian dictatorship, and filling prisons with political prisoners, we still inevitably hear the same refrain—from civil activists and political leaders who have now joined the opposition and lead the protests, from arrested and tortured demonstrators, from newly formed opposition movements, and from the fifth president, who has become a symbol of democracy: “Dream is acting in a way that will soon make it resemble the National Movement government.”

In other words, it’s not quite that brutal yet, but soon it will be. And if those who have been beaten and tortured think this way, it’s hardly surprising that viewers of Imedi TV, comfortably settled at home and favorably disposed towards the Russian regime, are basking in bliss. One thing is clear—this is an era of great repression. Those who once despised the National Movement now find themselves labeled by the Russian regime as part of a collective National Movement and treated exactly the same way as the original members. Today, we are experiencing the personal and societal consequences of the Russian regime’s violence: unlawful imprisonment, blatant violations of human rights, and the disregard for the principles of justice, freedom and equality.

What should be the ethical attitude of society towards prisoners of conscience when it is obvious that the system violates human dignity and freedom? One part of society is silent out of fear or indifference, and the other part is fighting against this injustice, but it is obvious that what is happening now in Georgia does not only concern and harm an individual, but also society as a whole, because justice is everyone’s responsibility, and every unjustly imprisoned person is a burden on the public conscience.

Perhaps the most striking example of the importance of collective responsibility was given by Rustaveli: People who live successfully and comfortably abandon their personal ease, leave everyone and everything behind and unite for a greater purpose. Tariel, Avtandil, Pridon, Patman, and Asmat fight together to free Nestan-Darejan, the prisoner of conscience in “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin”, from the fortress of Kadjeti. Nestan’s imprisonment takes on new significance today as we witness how the system turns people into both moral and physical prisoners simply because they remain true to their ideas and values.

Being a prisoner of conscience means bearing moral responsibility—being willing to endure pain, suffering, separation from loved ones, violence and isolation, yet refusing to surrender the right to free choice. Nestan-Darejan faces precisely such a moral dilemma: She must either submit to her father’s will and marry a foreign groom she has never even seen or defy his wishes and fight for her freedom. She knows from the very beginning what opposing Parsadan might lead to—leaving her homeland, persecution, separation from her beloved, tears and suffering. Yet, preserving her individuality on the one hand and upholding justice on the other are so vital to her that she chooses the path of confrontation over conformity. For her, love is a matter of freedom and dignity, not merely an expression of romantic feelings or the fulfillment of her father’s desired political or social aspirations.

Particularly significant are Nestan’s two letters sent from Kadjeti. One is addressed to Patman—a letter of gratitude for her solidarity. The other is meant for her beloved, revealing that imprisonment is, for her, a challenge that will ultimately strengthen their love even more. The suffering she endures in captivity becomes a sacrifice offered for hope and a greater purpose.

Nestan-Darejan’s story has become a moral lesson for contemporary Georgia, teaching us that freedom and dignity are such fundamental values that any sacrifice and suffering in their defense is justified. Today, our prisoners of conscience affirm this truth through personal self-sacrifice for the common good, preserving the very principles upon which any nation’s freedom is built.

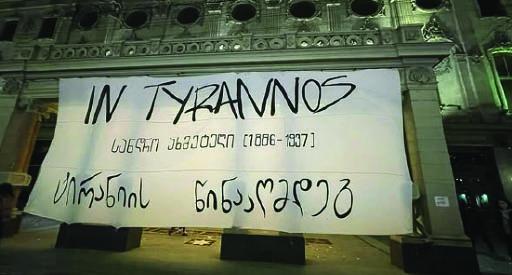

And finally, as Merab Kostava once said: A bird in the sky is merely an abstract symbol of freedom—true freedom is born within prison walls, in the struggle with them.