Author : David Khvadagiani

Never forget that what was, is the same, and what is, will be the same forever. Be absorbed in the contemplation of all the dramas or individual scenarios that you know through

personal experience or the accounts of historians. Imagine, for example, the palaces of Hadrian, Antoninus, Philip, Alexander or Croesus: the performance is always the same,

only the actors change.” Marcus Aurelius, Meditations (X, 27)

Millennia have passed since the Meditations of the deceased Marcus Aurelius were found in his military camp, but not only has the ‘performance’ of the Enlightened Emperor retained its significance, no one has since been able to describe with such precision and depth the essence of history and historical memory.

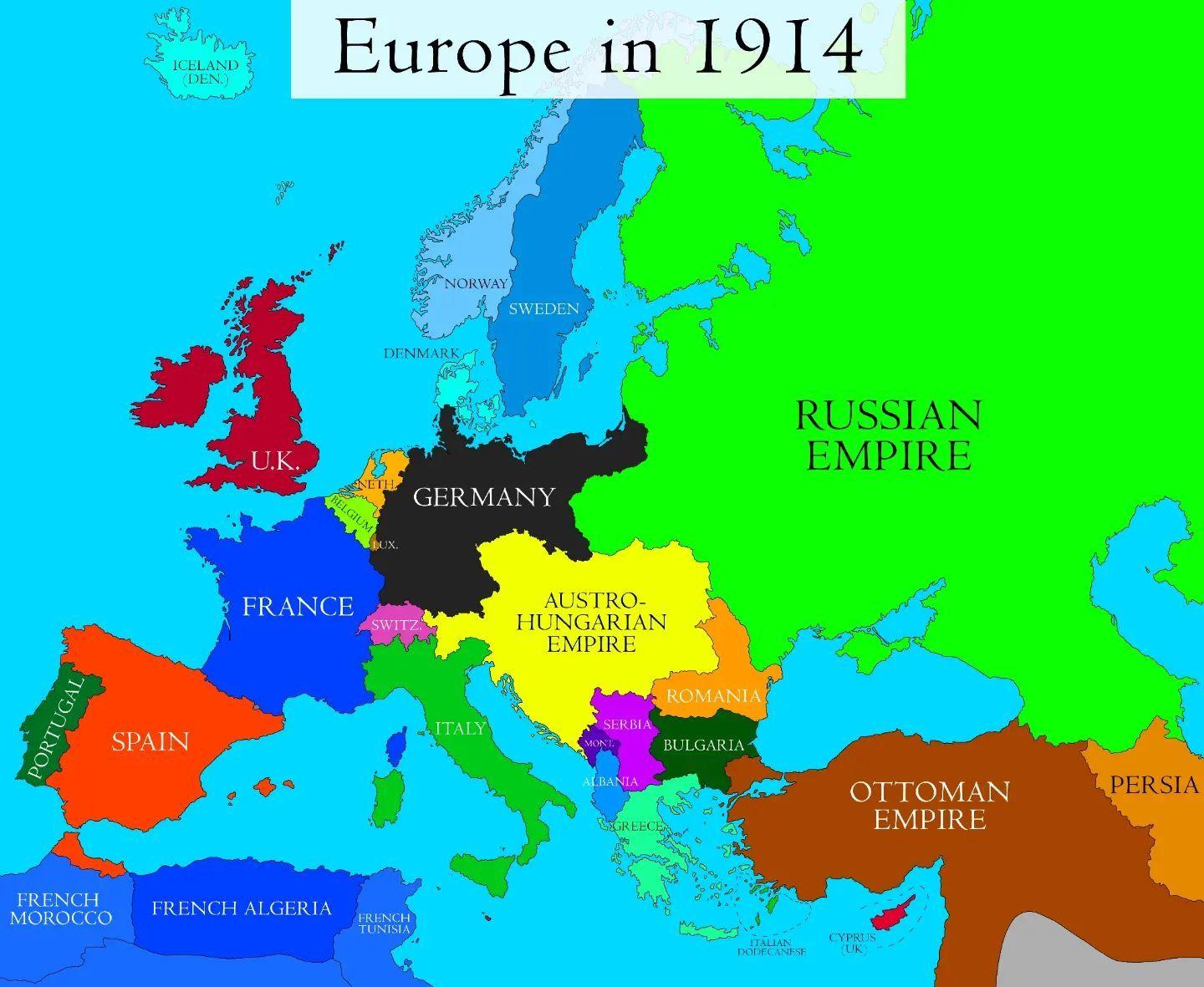

Historical memory, especially the study and understanding of recent history, is a characteristic feature and advantage of European societies. From 2014 to 2018, the 100th anniversary of the start and end of the First World War (then referred to as the “Great War” or “World War”) was marked. Almost every country in Europe was involved in the global conflict, which changed the course of mankind’s development. This war marked the end of the era of great empires and gave rise to the political order of the modern world. A century later, these countries commemorated the war appropriately, holding numerous scientific conferences and events.ს.

Europe at the beginning and end of World War I

Europe at the beginning and end of World War I

For Georgia, as for many other countries, the 1910s and 1920s were associated with very important commemorative dates, although the Russian regime in Georgia never thought to start the process of restoring historical memory—on the contrary, from 2012 onwards, the regime methodically began to restrict access to archival spaces, which remained constantly out of the public eye and posed a problem for small groups of researchers.

In 2023, the constant deterioration of the archival policy reached its logical end when the Russian regime closed the archive of the Academy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which combines the archives of the KGB and the Communist Party of Georgia, without the study of which it is impossible to expose the Soviet past and the crimes committed by Soviet Russia in Georgia.

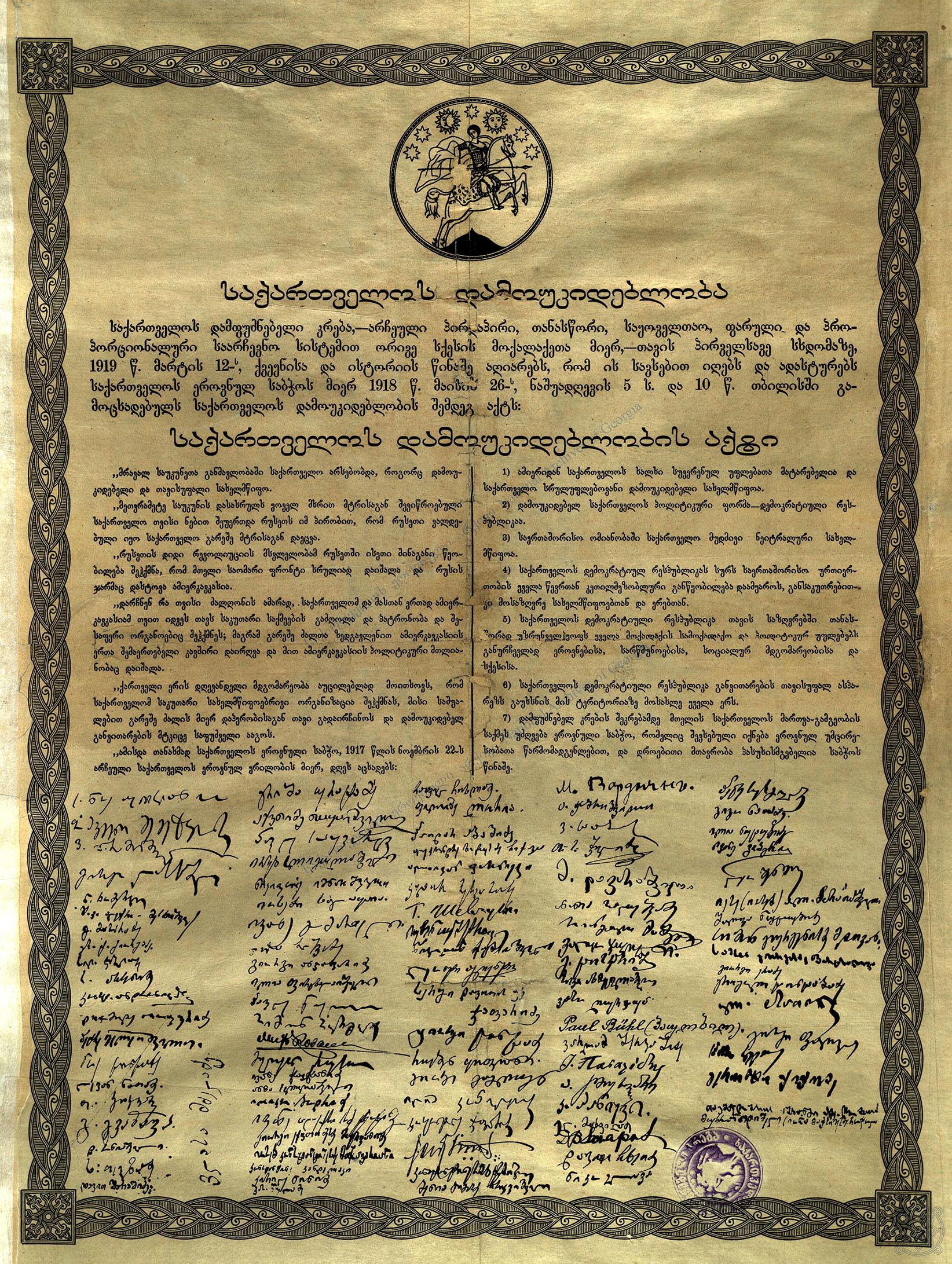

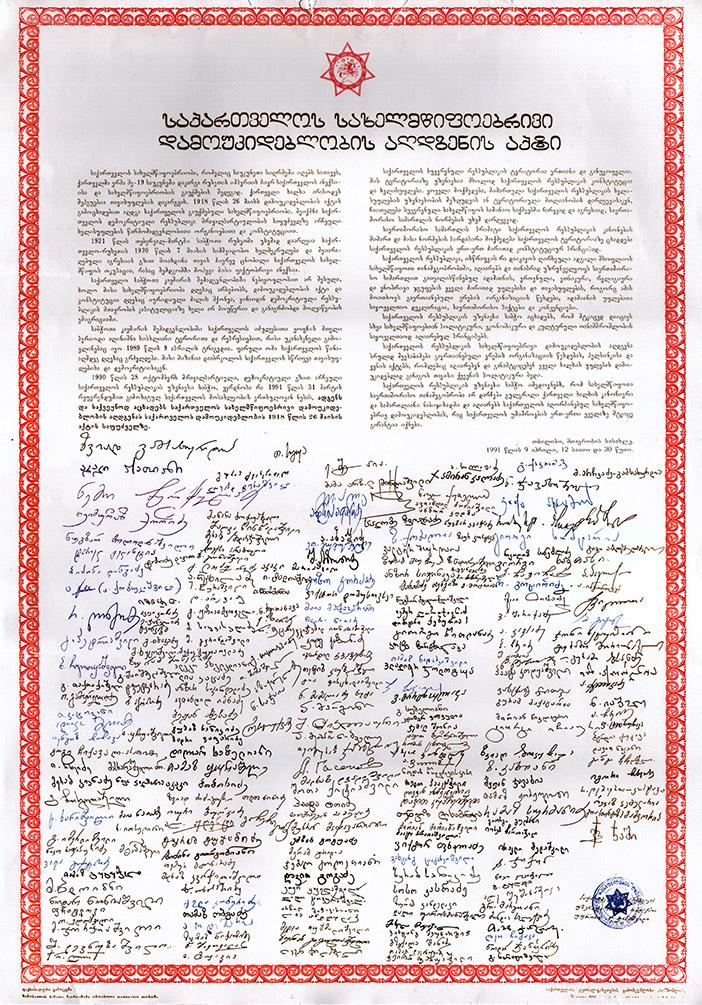

Act of Independence of Georgia 1918 and Act of Restoration of State Independence

of Georgia 1991

Access to the National Archives of the Ministry of Justice, especially the Archives of Recent History, also became extremely complicated. Most importantly, in October 2023, under unclear circumstances, the film repository of the National Archives burned down, which was a huge loss for the research perspective of recent history. To this day, the system remains silent on the matter, and the cause of the fire has not been investigated.

It is noteworthy that the most significant archives of the KGB and Communist Party lack proper infrastructure and dedicated facilities, not to mention clear structural affiliation. In any developed country, particularly in Eastern Europe—such as Poland and the Baltic states where they have experienced a totalitarian past and Soviet occupation—archival funds are typically managed by national memory institutions. These institutions operate within a transparent system and conduct essential research. In contrast, in Georgia, these archival funds remain under the control of the least transparent and most repressive entities—the Ministries of Justice and Internal Affairs.

The first coalition government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. From left to right: Shalva Alexi Meskhishvili,

Noe Ramishvili, Noe Zhordania, Giorgi Laskhishvili and Giorgi Zhuruli

The most significant phase of our modern history was in the teens, twenties and thirties of the last century. This period still has a fatal influence on modern socio-political processes and can be called the starting point of our modernity. This story begins with the course and consequences of the First World War; Georgia, as part of the Russian Empire, was involved in one of the largest military theatres of the conflict, the Transcaucasian Front, which passed through the historical territory of the country. On both the Transcaucasian and Western fronts, tens of thousands of Georgian soldiers and officers conscripted into the Russian army took part in the war, suffering unimaginable casualties, although today this colossal loss has been completely erased from our collective memory and can only be found in yellowed print media or archives. Society still remembers only the catastrophic human losses of Georgia in World War II. However, this oral and superficial memory is also on the verge of oblivion and erasure due to inadequate research and lack of a memory policy.

The history of the First World War is of paramount importance for Georgia as an independent state, because it was the result of the First World War and the subsequent Paris Peace Conference that decided the fate of the independence of small nations, which was impossible before. For example, it is interesting to try a little experiment: if we search for maps of Europe in 1914 and 1918 using the Google search engine, we will find two completely different political maps of Europe; in 1914 with large empires, and already in 1918 with many democratic republics, especially in Eastern Europe, including in the South Caucasus.

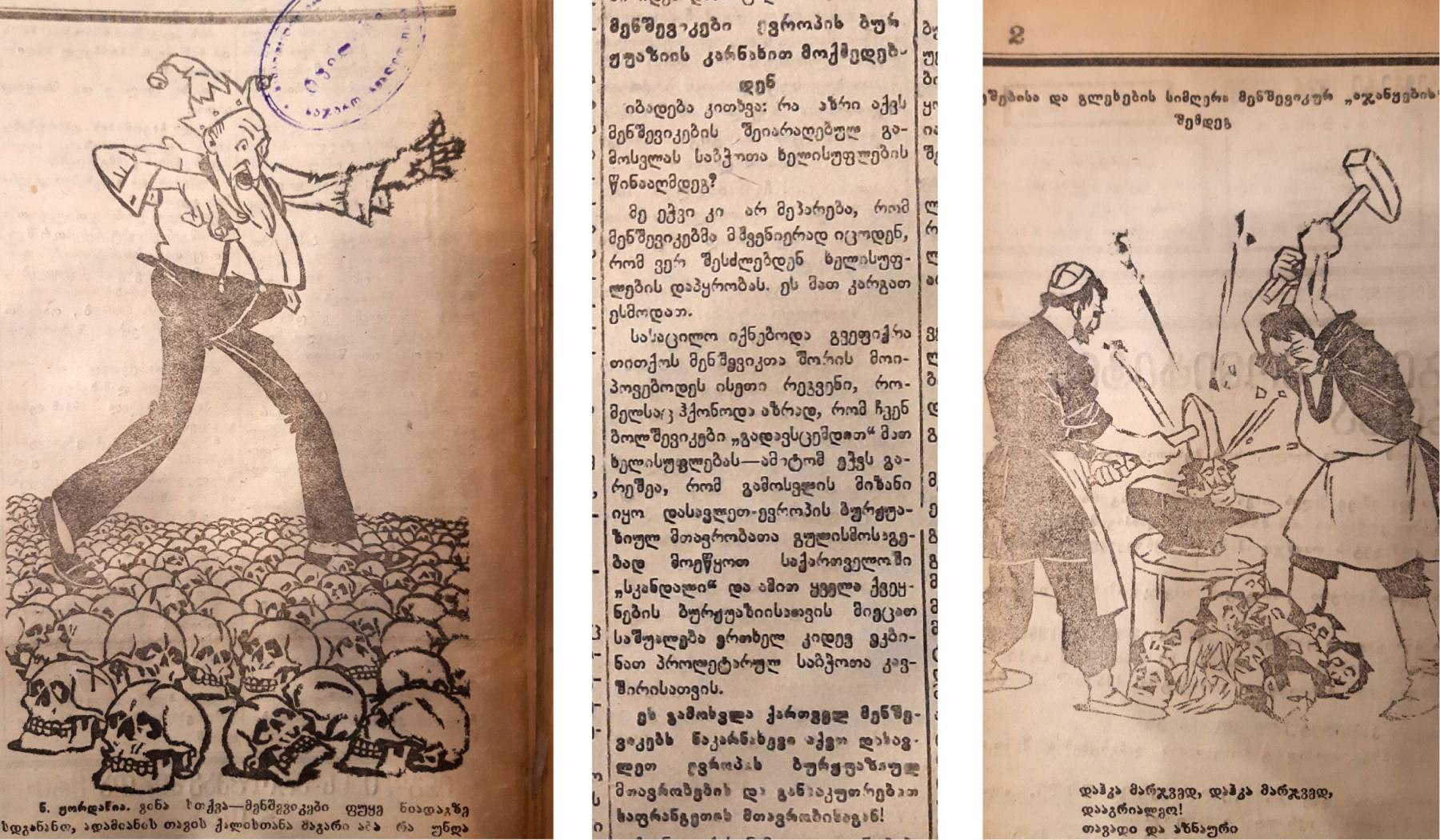

Newspaper “Communist” N3, March 4, 1921

The most important period of Georgia’s recent history is connected precisely to the end of World War I and the collapse of great empires, when the February Revolution of 1917 overthrew the Russian Empire, and soon Georgia became an independent democratic republic. The history of Georgia from 1918 to 1921 was thoroughly erased and falsified by Soviet Russian propaganda. As a result, several generations, even their educated and intellectual segments, either have a superficial understanding of this most important period in our country’s recent history or have a distorted and falsified version imprinted in their consciousness. Even today, the wider society is completely unaware of the history of 1918-1921, when, on 26 May 1918, the first modern, contemporary, democratic Georgian state was established after the feudal era—the state of which we are the legal successors today.

To this day, there are often pointless debates in social and other discussion forums about which is the real Independence Day of Georgia, 26 May or 9 April? Do we have a 100-year-old state or a 34-year-old state? If we visually perceive both acts of independence, the answer becomes simple: the modern Georgian state was created in 1918, which was forcibly ended in 1921 by the Soviet-Russian occupation. The capitulation was not signed or recognized by the legitimate representative government of the Georgian people and the Constituent Assembly, who fought for decades in exile for non-recognition of the Russian occupation, on the basis of which the state independence of Georgia was legally restored on 9 April 1991.

he political processes that developed in the South Caucasus in 1917-1918, related to the convocation of the Transcaucasian Sejm on 10 February 1918 (which legally formalized the secession of Transcaucasia from Russia) and the creation of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (DFR), which united Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, have also been forgotten or distorted. According to myths and legends, later fueled of course by Soviet propaganda, the Transcaucasian Republic was supposedly created by the leaders of the then-dominant political party, the Social Democrats, because they were in no hurry to declare Georgia’s independence. But the reality is quite different, because the political center of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic was in Tbilisi, and Georgian Social Democrats dominated the government—the Chairman of the government was Georgian Akaki Chkhenkeli, and the Chairman of the Sejm was also a Georgian, Nikoloz (Carlo) Chkheidze. The Transcaucasian Federative Democratic Republic was a highly significant state and political project aimed at the unity of the South Caucasus and the maintenance of the strategic Baku-Batumi corridor, which ensured the continuous interest of major Western European powers in the region. However, the intense conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan quickly rendered its functioning impossible, leading to its swift dissolution.

The main challenge for independent Georgia was finding a foreign protector and orientation that would shield the newly established Georgian democratic state from external aggression amid a turbulent international environment. Germany emerged as such a protector, making the declaration of independence and the halting of the Ottoman army’s aggression a realistic prospect. However, in November 1918, World War I ended, and Germany was defeated, once again placing the Georgian government and diplomatic corps before a significant challenge. Here emerges the concept of “neutrality in international warfare”, as stated in the Act of Independence. In reality, this meant non-alignment in the wars of the great European empires rather than neutrality concerning Russia—a misinterpretation that persists to this day. In this very context, victorious Britain viewed Georgia, the former ally of its defeated adversary, Germany, with disfavor. The tragic 1918 Armenia-Georgia war was a reflection of this geopolitical reality, as the independent Democratic Republic of Armenia was a British ally, and its interests aligned with those of the British.

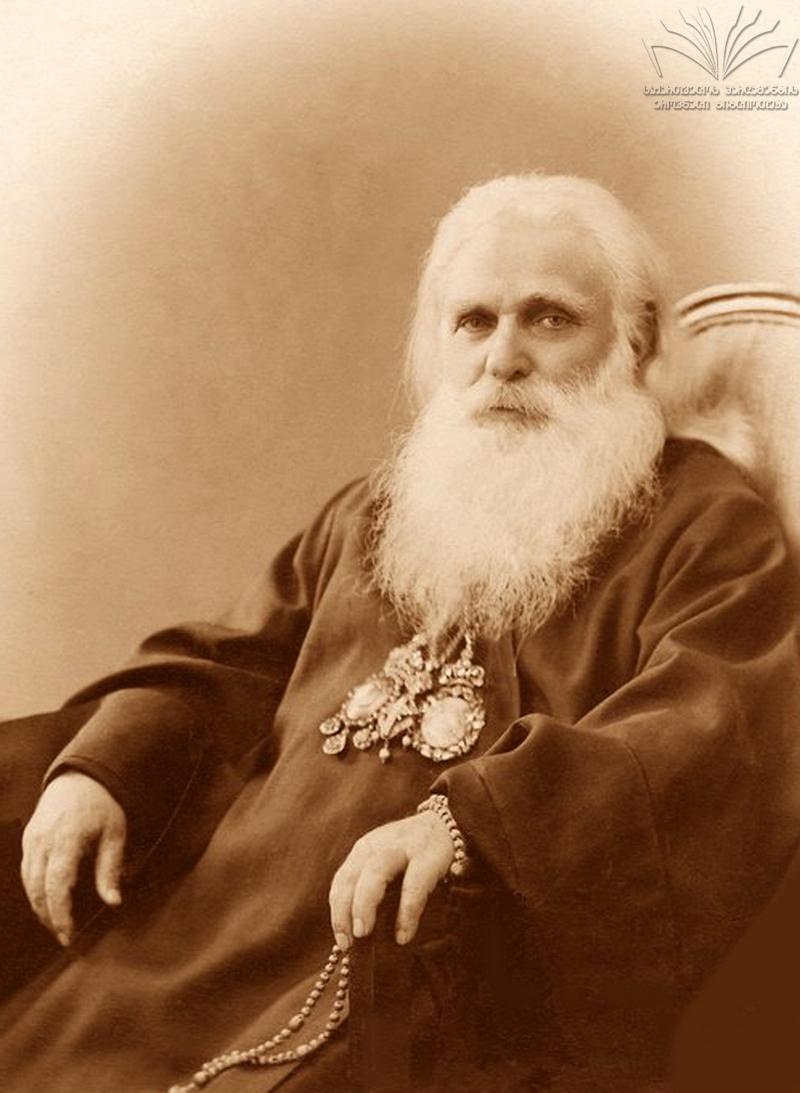

Kote Andronikashvili

Chairman of the “Damcom”

The breakthrough of the blockade and Georgia’s de facto recognition as an independent state in January 1920 should be credited to the efforts of the Georgian government, political elite and diplomatic corps of the time. This achievement was followed a year later on January 27, 1921 by the full legal—de jure—recognition of the Democratic Republic of Georgia by the Supreme Council of the victorious states of World War I, where Britain and France played leading roles. A significant contribution to this process was made by France’s newly elected Prime Minister, Aristide Briand, who actively considered the threat posed by Russia and saw the support of nations liberated from the Russian Empire as a “sanitary cordon” to contain it. He viewed the strengthening of their statehood and the supply of arms as key measures to achieve this goal. Once legally recognized, Georgia’s admission to the League of Nations became a realistic prospect and only a matter of time—something that Soviet Russia, Vladimir Lenin, and especially the People’s Commissar for Nationalities, Joseph Stalin, understood well. Georgia’s independence and its pro-European course posed a personal threat to Stalin in the midst of the life-and-death political struggles unfolding in Moscow. At this critical moment, Stalin succeeded in persuading Lenin to launch a military intervention against Georgia. The decision for intervention was taken in Moscow on the same day, 27 January 1921, that Europe granted de jure recognition to Georgia.

Catholicos-Patriarch Ambrose Khelaia

Before the Russian-Georgian War of 1921 and Soviet Russian occupation, democratic Georgia successfully repelled several threats. Together with the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan, with which it signed a military cooperation agreement in 1919, Georgia managed to halt the advance of the Russian Volunteer Army (“White Russians”). It also repelled an attack by Soviet Russia (“Red Russians”) in 1920, while continually suppressing Bolshevik-orchestrated uprisings and fighting a relentless battle against Soviet espionage and subversive activities. However, in the fateful war of 1921, Georgia was defeated—Russia was one step ahead of Europe. Although France had already begun supplying weapons to Georgia following its de jure recognition—and even provided artillery support from its naval fleet in the Black Sea during the Russo-Georgian war, assisting Georgian forces in Abkhazia against Russia’s Kuban 9th Army—it was not enough to prevent the Soviet occupation.

Parallel to the Russian-Georgian War, on February 21, 1921, a momentous event in Georgia’s statehood history took place. After two years of continuous work, the Constituent Assembly of Georgia adopted the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia—a document whose progressive nature is still acknowledged by international experts today. The constitution abolished the death penalty, a symbolic step toward Georgia’s development and Europeanization. However, in reality, it remained in effect for only a few weeks. Shortly after, under Soviet Russian occupation, the opposite became true—death and mass extermination of people became a common occurrence.

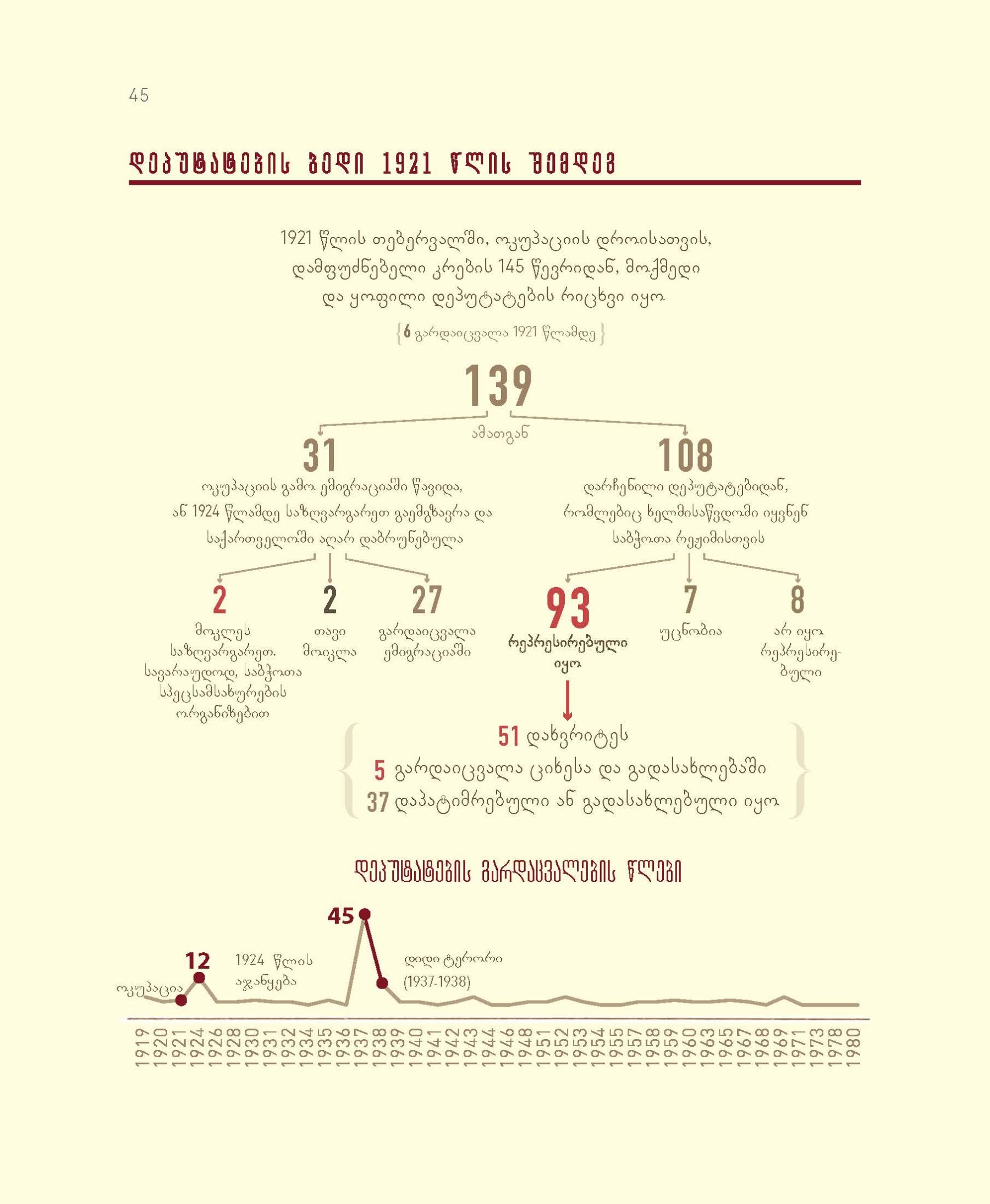

Newspaper “Musha”, September 1924

According to the myth created by Soviet propaganda, which later became a widespread legend, “the Georgian government fled and abandoned the country”. In reality, only a small part of the then government and the Constituent Assembly went into exile, as decided at the last session of the Constituent Assembly held in Batumi on 17 March 1921, so that the enemy would not achieve its main goal of forced legitimization of the occupation by capturing the head of the government. It should be noted that during the ceasefire negotiations in Kutaisi, the representative of the Georgian government, the deputy chairman of the government, Grigol Lortkipanidze, did not sign the capitulation. The majority of the government and the Constituent Assembly remained in Georgia and joined the resistance movement. For example, 51 members of the Constituent Assembly were physically destroyed (shot) by the Soviet-Russian repression, 11 of them during the 1924 uprising, others during the Great Terror of 1937-1938, while the majority of the rest were repressed—repeatedly arrested and deported (see the chart).

In 1921, following large demonstrations that were repeatedly suppressed by the Russian occupying regime, resistance movements began to gain momentum, starting with the uprising in Svaneti and continuing with the rebellion in Khevsureti in 1922. These movements gradually grew stronger, became more organized and multiplied. This resistance was further consolidated with the formation of the Independence Committee (Damkomi) in 1922, where Georgian political parties—Social Democrats, Social Federalists, Social Revolutionaries, National Democrats, and others—agreed to join forces in the fight against the Soviet Russian occupation regime.

In 1922-1923, several historical events took place which played a decisive role in the political life of the time, but have since been carefully forgotten and erased from our collective memory. These include the process of “self-liquidation” of Georgian democratic political parties, which was forcibly organized by the occupying authorities and their terror machine, the “Cheka” (Bolshevik secret police); the split within the Communist Party of Georgia, known as the National Uklonist Movement, when the elite of the Georgian Communist Party rebelled against the de facto informal rule of Sergo Ordzhonikidze and the KavBureau (the Caucasus Bureau of the Russian Communist Party, later the Transcaucasian Regional Committee), which Sergo Ordzhonikidze neutralized with the help of Stalin from Moscow. This led to the resignation in protest of the entire Soviet Georgian government, which was subsequently ‘purged’ by the regime.

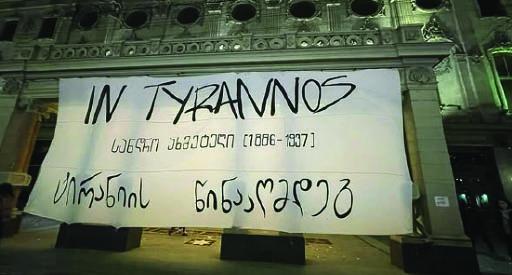

The political crisis reached its climax with the anti-Soviet national uprising of 28 August 1924, which, although defeated, significantly shook the occupying regime. The uprising was followed by harsh repression by the Russian occupation regime. Around 5,000 insurgents were killed, a significant loss for the resistance movement. However, the resistance did not cease; the surviving fighters and activists continued to fight for the restoration and strengthening of illegal organizations.

Since 1926, the internal split within the Communist Party of Georgia continued, primarily taking the form of a Trotskyist movement. Former National-Uklonists were actively involved in this movement as well, which again ended with mass reprisals, arrests, and deportations.

“Such a catastrophic event as collectivization has been erased from our collective memory, and there is not a single fundamental work dealing with it. Collectivization changed the entire model of economic development after the New Economic Policy introduced in the 1920s, and indeed we are still reaping its negative consequences. The fierce resistance to collectivization from the late 1920s to the mid-1930s, when the population revolted en masse against the establishment of collective farms, has been completely forgotten. This process led to no fewer casualties and clashes than the resistance of the 1920s.”

In reality, the mass repressions and terror of 1937-1938, aside from purging the old cadres of the Communist Party and the intelligentsia, and eliminating the remnants of political opponents, primarily targeted the prosperous peasant class that opposed the predatory policies of the Soviet regime, which was most evident in the collective farming process. The terror of 1937-1938 ended an entire era, one that began with independence and continued through the Russian occupation, physically destroying the generation of people who created independent Georgia, as well as even those who participated in its destruction and occupation.

The history of the years 1917-1921 and then 1921-1938 can be considered a textbook example of the process of independence and Russian occupation, a process that has been forgotten to this day and is carefully locked away in archives. Due to the aforementioned problems, countless historical documents are facing the threat of destruction—documents that could guide us in understanding how the historical process began in 1918, a process that continues to this day. These documents would help us fully grasp what the beginning was like, understand where we stand today, and identify the challenges we face in the future. For modern active citizens, this would serve as a form of social immunity, enabling them to easily avoid and neutralize Russian propaganda hooks. Russian propaganda, primarily based on the falsification of recent history, often manages to disorient and manipulate opponents through the control of this process.