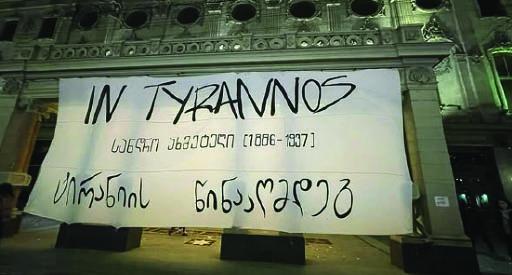

Author : Buba Kudava

The land was in turmoil, and Giorgi II, seeing his strength wane, laid down his crown and placed it upon the brow of his son, who was but sixteen years of age. From his earliest days, young Davit showed great promise, and thus did his feeble father, lacking the will to rule, anoint him king. And lo, fortune smiled upon this deed—for of all his days upon the throne, this alone did weak Giorgi accomplish with wisdom: he passed the scepter unto him who would be known as the Builder. Long have men spoken of this as the dawn of Georgia’s proudest age. Even now, many hold it to be true. Yet as the years unfurl, questions arise, doubts stir—was it truly thus? Or does some shadow lie hidden within this tale?

Like many theses rooted in our beings, this version of Davit the Builder’s accession to the throne also originates from the Life of Kartli. But there is one question we must ask ourselves every time we turn the pages of the chronicles: was it really so or rather did the author of the stories want us to believe it so.

Let us begin with this—such a precedent we do not have. A man, healthy and whole, removed the royal crown and, with his own hands, set it upon his son’s head. He did not name him co-king or co-emperor, as had been done before. He did not take the monastic vows, as others had. Nor did he lie upon his deathbed, bidding farewell to the world. Nay, he simply awoke one day, beheld his own weakness, and surrendered the throne. He stepped down and departed. Departed, and left the kingdom to his son—a man of fifty years yielding power to a boy of but sixteen!

Let us go on to say that there are not many such cases in the history of the world. Tradition and experience have it that a king either appoints an heir as a co-ruler, dies, is assassinated or banished or chooses an ecclesiastical office and leaves the country. Why is it that aging or fatigued kings do not quietly and voluntarily leave the throne to vigorous heirs? This is a separate question. Of the many reasons (lust for power, the fragile security of the uncrowned monarch and his cronies) the most important is perhaps the following: precedents are a dangerous thing, they can become a trend that whets the appetite of each successive prince. So be kind and wait your turn and your fate—that was the royal philosophy.

Let us turn to the sole (!) surviving account of young Davit’s ascent to the throne and lend our ear to the Chronicler:

“At that time, Davit was sixteen years old, and the Chronicler was three hundred and nine (that is, the year 1089). And his father himself crowned him king. Yet it would be truer to say that the heavenly Father Himself found Davit and blessed him.” What follows are verses from the Psalms, along with subtle and overt allusions to the notion that just as the Lord anointed the biblical Davit, so too did He lay His hand upon our Davit. In other words, it was divine will, and Giorgi was but its humble instrument—something of that nature.

That’s all it is. And yet, how so much this blessed anonymous person knew and how stingy he was with his words! There are so many details we’re interested in, which he remains silent about: What exactly led Giorgi II to this decision? What forced him, who forced him? Where did the former king go? Where did he live afterward and what did he do? Did he help his son to govern the state or did he distance himself from the royal court? What kind of relationship did father and son have after this? How long did Giorgi live and where was he buried in the end?

One gets the impression that Davit’s chronicler skillfully avoids these and other questions by quoting Scripture. Suspicions are further aroused by the fact that the author of the Life of Davit never mentions Davit’s father after Davit’s accession to the throne! He is writing a royal history about the king and is not even interested in the death of the father who blessed his crown. He devotes an entire passage to the death of Giorgi of Chqondidi, the king’s right-hand man. And there he adds, “King Davit put on mourning clothes and mourned him like a father, and more than a father.” Those who study subtexts will not fail to notice that this “more than a father” is written here not merely to honor his mentor and fellow warrior.

And yet, in the commemorations appended at the end of the famous monument (decree) of the Ecclesiastical Council of Ruis-Urbnisi, Giorgi II is mentioned not only among the living, but at the head of the living, even before Davit the Builder! Davit holds the Council 15 years after his accession to the throne, and imagine, during this time his father is alive, and Davit’s chronicler nowhere mentions this fact, not even in passing. Moreover, according to another source, it seems to be confirmed that Giorgi, the former king, died in the 23rd year after abdicating the throne!

So why would Davit’s chronicler not mention Giorgi’s existence? This silence does not seem coincidental, so what is the news from the royal court hiding from us?

It is not that Giorgi was forced; it is not that the king did not want to go anywhere and was simply deposed or forced to resign; it is not that there was a conspiracy and a coup d’état.

He placed the crown on his son’s head with his own hands—that might be the truth, albeit beautifully packaged. “With his own hands” doesn’t mean by his own will and decision. If Giorgi II had been forcibly removed from power, they would probably have taken the matter to its logical conclusion and even demanded that the ceremony of the transfer of the crown be carried out officially. They wouldn’t have given him any choice, because the young king would need legitimacy, and the conspirators would leave no room for any talk or thoughts that he was not a king but a violent usurper of the throne.

Today, more and more historians are skeptical about the story of his voluntary abdication, and the version of a coup d’état is slowly gaining ground, but according to this theory, the conspirators are good, progressive and concerned about the country’s ills. They see Davit as the path to salvation, so they take the initiative. They continue to stand by him afterwards, and you know what happens next. According to one view, this group is led by the Grand Chancellor, Giorgi, who was later given the title of Chqondidi by Davit and became Davit’s first Vizier and supporter and leader of all major affairs.

It is worth reflecting on Davit’s role and significance in the upheavals of 1089. Although a 16-year-old of that time differs from today’s 16-year-old in terms of maturity perception, especially when it comes to a noble raised for the throne, Davit still seems too young to have spearheaded the rebellion on his own. It is only natural to assume that more seasoned and influential figures stood at the forefront, guiding events with their experience and authority. Yet, Davit’s admirers might argue—why should we dismiss the possibility that Davit revealed his true nature even in his youth and took the reins of the movement himself? Would that be surprising from a person of Davit’s ability?

Finally, let us delve into the matter and ask—who truly stood in Davit’s circle, and was this circle truly his own? What is there to dispute? They were feudal lords, and the very nature of power whispers that the mighty of this world sought not a sovereign but a puppet, a ruler to serve their own ambitions. Yet, such designs do not always unfold as intended. Thus, Davit grew strong, and in accordance with that same immutable law, he first turned against those who had placed the crown upon his head. If we follow this thread, we shall find among the architects of his enthronement the very figures whom he would later crush without mercy in the earliest days of his reign.

Oh my God then, should we truly count Liparit Bagvashi and his kind among Davit’s initial circle? Should we be grateful for their insatiable ambition and miscalculations that hastened Davit’s early coronation? The questions are endless. And new ones will certainly arise, each as unresolved as the last. Yet history does not dwell on uncertainties—it judges by results, weighs by outcomes.

Thus, whether the father crowned him willingly or unwillingly, whether Davit himself reached for the crown or was lifted to it by his entourage, whether they placed certain hopes upon him or entirely different ones—all of this fades before one undeniable truth:

The 16-year-old boy proved himself right—and what a triumph it was. A triumph beyond the imagination of those times, be they opponents or supporters, skeptics or optimists, short-sighted schemers or far-seeing strategists. Even the conspirators, who thought they were shaping the future, could not grasp the true nature of the ruler they had placed on the throne. Nor could the young king himself yet fathom the great battles that awaited him.