Author : Guga Sulkhanishvili

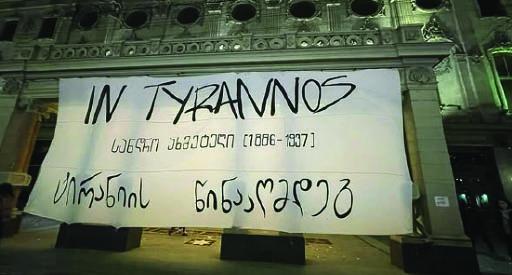

I read a book titled Зима тревоги нашей back in my childhood. It was lying by my brother’s bedside, I got curious, and he recommended it to me. Forgive me, but back then, such books were only available in Russian. The Winter of Our Discontent—in English if you insist. John Steinbeck’s novel was published in Georgian in 2023 under the title The Winter of Our Anxiety. To be honest, the novel deals with entirely different anxieties, but its title perfectly suits this winter of ours.

Anxiety and turmoil have never truly left us—neither in winter nor in any other season. Yet, this winter feels different. And I’ll tell you something: political events and protests have never felt as personal to me as they do now, not even in April 1989. I have always been there (and I say this without any self-praise) whenever I felt that Georgia’s path toward the West was being obstructed by the government’s missteps. I stood there believing that governments would come and go, but the country’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations would eventually regain momentum. Just like that, in a general way, I was thinking about the political future of the country.

This winter the parent in me awakened. First, a very real threat emerged—violent beasts operating under the name of ‘Spetsnaz’ could physically harm my children, so I could not stay at home. Second, I refused to let my children grow up in a country deprived of freedom and dignity, like the one I lived in until I was 17. When I say I won’t allow it—who am I to wield such power? But I do know this: I must do everything, exhaust every effort, to prevent it.

Winter is long, cold, and often wet. You just want to stay in a warm house, watch films, football—or simply do nothing at all. I’m tired of going to Rustaveli as if it were a job. That, too, is human. It has taken more and more effort to push myself forward. My own will and parental instinct had become no longer enough.

And then, the instinct of my descendants awakened in me. I had never stood at rallies thinking about my grandfathers, my parents, or my brother. I stood on behalf of myself, regardless of what they had done. But suddenly, that changed. A wave of shame washed over me—shame before them. Every one of them had fought against Russia, each in their own way, yet without exception. And this gave me a new, absolutely inexhaustible energy.

My grandfather, Sulkhan Sulkhanishvili, was born in Telavi in 1904. Our family was noble, holding estates in Atskuri, and the nobility there were very close-knit. Kakutsa from Matani, it seems, used to visit our family often. In 1991, my father wanted to buy a house in Atskuri, in our ancestral lands, and we would often go there on weekends to search. One day, we met an elderly man. When he learned that my father was Sulkhan’s son, he told us the following story: In February 1921, there were many guests in the family, including Kakutsa. The weather was fine, and they were sitting on the balcony. Sulkhan came to them and started speaking harshly: “The Russians are coming and you’re sitting here idly, drinking wine.”

Kakutsa called out, “Boy, come to your senses! What are you talking about?”

Sulkhan left, gathered boys of his age, and said, “I’m leaving to fight the Russians.” Kakutsa and the elders couldn’t help but laugh. My grandfather was just 16 or 17 years old at the time. Back then, guests would usually stay for several days. My grandfather came back after 3 or 4 days, head down, clearly embarrassed. Kakutsa asked, “Well?”

“Have you chased the Russians away?”

“They keep coming like ants,” my grandfather replied.

Then, my grandfather stood by Kakutsa during the 1924 rebellion. These stories are well told by Zaira Arsenishvili in her book, Wow, the Village (ვა, სოფელო), and I won’t tire you with all the details.

Telavi historian Tengiz Simashvili showed me the prison cell from which my grandfather, who had been sentenced to death, managed to escape. In Kakheti, they took everything from him—his house, yard, and land. He couldn’t stay there anymore and began posting proclamations in Tbilisi. There, too, they pressured him heavily. Along with his close friend Elizbar Makashvili, he decided to flee the country via Batumi. But the evening before their departure, they arrested him on Besiki Street while he was posting another proclamation. I also have the interrogation protocol from the same Tengo Simashvili. In short, my grandfather was exiled to Kazakhstan for life. He married there, and my father was born in Kazakhstan as well. Somehow, he managed to return later. He passed away on November 7, 1987. My father would often laugh, saying he died on the birthday of those he had hated most throughout his life.

A frame always hung on the wall of his room with four photos: Kakutsa Cholokashvili, Sasha Sulkhanishvili, a photo of Kakutsa and Sasha together and Kakutsa’s grave in France. If you believe me, displaying Kakutsa’s photo in those times was no small matter.

Yes, on that evening in 1924, when my grandfather was arrested, Elizbar Makashvili managed to escape. He eventually settled in Paris. The first letter from him arrived for my grandfather in 1986. I was there when he read it, and tears streamed down his face.

My father worked as the head of a department at a scientific institute. In Soviet times, it was understood that if you wanted to get ahead, you had to join the Communist Party. That, however, was out of the question for my family. My mother, too, kept a stash of banned books hidden here and there: Solzhenitsyn, and a book about the Six-Day War with Israel.

One summer, we were vacationing in Sioni. My family had rented a house, and some close friends visited us there. I must have been around 5 or 6 years old. They put me to bed, but I remember being woken up by my father’s loud voice: “Why can’t we if Holland, Belgium, and Denmark can?!” The next morning, I found out that the guests had expressed skepticism, saying that we, as a small country, could not live independently from Russia. Yes, this was the prevailing thought at the time. It was this mindset that made my father so bitter.

The other grandfather, my mother’s father, Datiko Purtseladze, was the grandson of Anton Purtseladze. His father, Levan, was a lawyer, and grandfather also enrolled in law school in 1919 at the newly opened university. When the Russians came, he joined the resistance, and his closest friend was Shaliko Makashvili, Maro Makashvili’s brother. When grandfather was going to Kojori, Shaliko was ill and couldn’t join him, and he asked my grandfather to keep an eye on Maro if possible, saying, “You know how reckless she is.” We all know the tragic end to Maro’s story. By the way, Niko Ketskhoveli was wounded in his left hand next to my grandfather. He could never use his left hand again afterwards.

Grandpa Datiko didn’t get a proper job until the 1950s. He didn’t try either—he wasn’t that kind of person. He was arrested in ‘38. In early spring of ‘37, when he realized he wouldn’t survive, he fled to Tusheti. He stayed there for a year, and as soon as he returned, they arrested him. They released him in 1940. My mother would tell me, with tears in her eyes, how he returned home. He remained silent about it but expressed his protest in his own way: in the sixties, he refused to become an academician. He also turned down an apartment in the academicians’ building near the Tea House.

When my brother perished in Abkhazia, grandpa was 90 years old and in good health. But after that, he broke down. “How can I be alive and he’s not? I can’t understand that,” he once told me. He passed away in 1994. He stayed friends with Shaliko until the end, as long as Shaliko was alive. I also remember Uncle Shaliko—a tall, stately man with good looks.

So now they want me to call Russians the good guys? That’s not going to happen. This won’t work, period. It’s in my DNA. Fighting Russia is part of my identity. Moreover, if something happens to me, I know for sure my children will fight. They are already fighting. It’s like the saying, “A leopard can’t change its spots.” It’s just not going to happen.

The other day, a friend came over. He’s very active in these protest movements of ours, much more than I am. I rarely tell this story, so it doesn’t come across as bragging, but that day I shared these stories with him in detail. Unexpectedly, he asked me if it was a weakness to not have such ancestors. I told him quite sincerely that they are our common ancestors. All of them! Everyone who fought against Russia is our common ancestor. They created our identity. They were defeated, but they created it. And now we stand! And we will not be defeated. And that’s why we want Europe — so it doesn’t matter anymore who is whose child and grandchild. Regardless of this, together we can create a modern, free, civilized, European state. We will stand until the end.

P.S. Uncle Shaliko was an artist. Once, he gifted my grandfather his painting for his birthday. It was a detail of Uplistsikhe. Just recently, probably two or three years ago, I turned it over and found this inscription on the back: “Endure, as this one has endured. Sh. Makashvili. ‘Kvakhvreli’, Uplistsikhe.”

We will not endure, Uncle Shaliko. We will win.