Author : Nana Kalandadze

No one truly remembers how they came into the world—how many grams of milk or spoonfuls of porridge they consumed each day. From early childhood, only a few vivid fragments remain, scattered across memory, preserved simply because they made a strong impression.

Yet as time goes by, you begin to realise that certain moments, objects, or situations from the past stay with you not just as memories, but as something you’re connected to in a more profound way. These fragments have been resurfacing in my mind for quite a while. Every now and then, one or another rises unexpectedly, tugging at my attention. So, I decided to give each of them its own ‘shelf’ in the archive of memory. The subject I want to begin with doesn’t belong to any specific time, place, or role in our lives. It is a physical and spiritual part of us, without which we simply would not exist in this world.

Yes, I mean parents.

In the past, death announcements were published daily on the fourth page of the Tbilisi newspaper. From the number of signatories, one could easily determine the circle of a person’s relatives, friends, or the sphere of professional activity of him and his relatives… On 26 March 1968, my aunt, at whose home I was temporarily staying due to my father’s illness, quietly placed the newspaper in front of me, folded open to the fourth page, where among many announcements I saw a single name, Grigol Kalandadze!

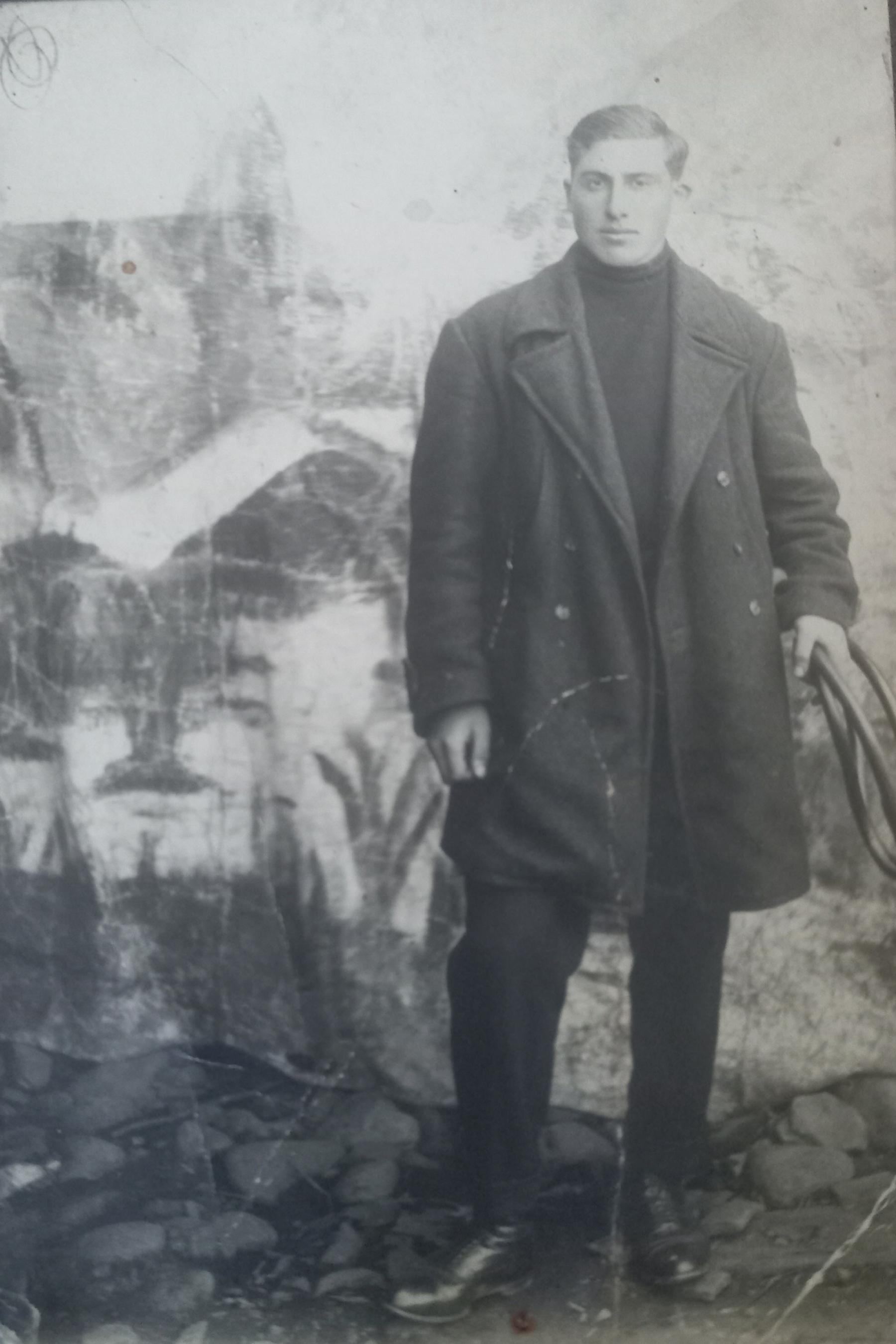

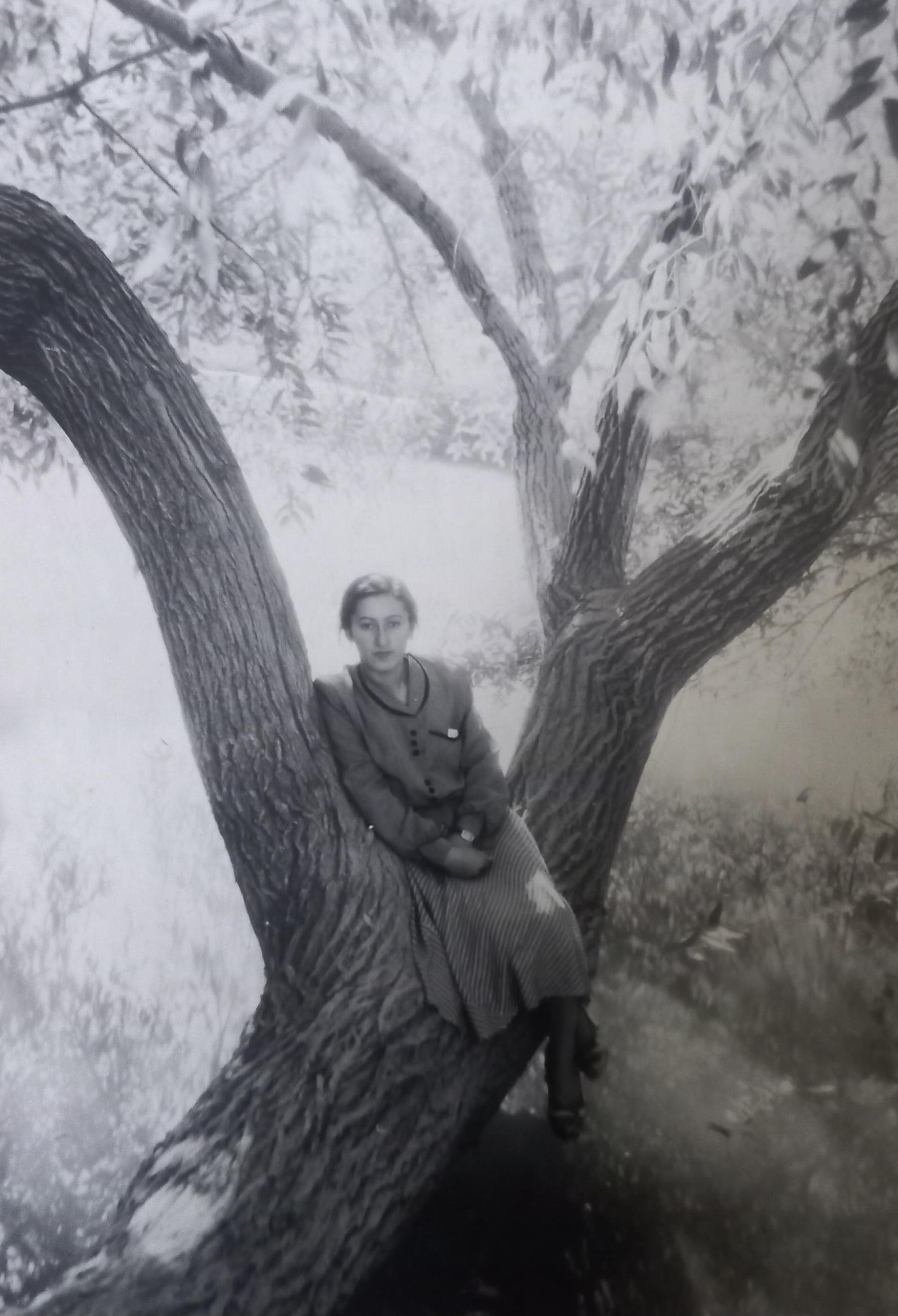

My father, Grigol (Grisha) Kalandadze, 18 years old,

a few days before his deportation to Siberia

Spouse... son... brother... sisters... friends... with deep sorrow...

I must have read those words ten times. Then the lines and letters began to blur, twist, and swirl until they all dissolved into one large, heavy drop that fell silently and painfully onto the newsprint…

I was only nine years old...

My father was tall, slim, and with strong shoulders... He had wheat-coloured hair with grey at the temples and green-khaki eyes (he often said he had also inherited the Zhgenti1 colours). He had a happy, pleasant laugh, was an excellent singer and a skilful performer of krimanchuli.

A classic Gurian — quick, hot-tempered, but soft-hearted, with a soul full of immense kindness and the capacity for boundless love. He was born in Chokhatauri and was absolutely crazy about the place. After returning from exile (what was he doing there? I’ll tell you later), he built an oda4 on the foundation of an old house with his own hands. He planted varietal hazelnuts along the path leading to Supsa and lined it with hornbeam trees. ‘The Odesa5 gets its special flavour from the kvevris buried at their roots,’ he used to say. He fenced the yard with climbing roses growing along a towering linden tree, made a winepress from an old chestnut cut down in the Bukistsikhe forest, planted rows of ‘black apple’ trees behind the pear tree known as ‘katsistava’, and even repaired the old kukhna-sakhli, the kitchen-hut.

This special love was deepened by a longing carried from childhood. To begin with, until the age of seven, he was raised in the village of Jvartsma, in the Bolkvadze family. Let me explain why: Our family’s close relative and irreplaceable helper, Iason Bolkvadze—father of eight daughters—was expecting his ninth child, while at the same time my grandmother was pregnant with my father. There were no ultrasounds or horoscopes back then. A person would be born and follow the path life set before them. No one knew in advance who was coming into the world. And since Iason never had the chance to fire a gun in honour of the birth of his son, he asked us: If you have a boy and I have a girl again, let me raise him at least to school age, I will not let a cold breeze touch him and apart for the maternal care of Pelago (his wife), the older girls will treat him like a brother.

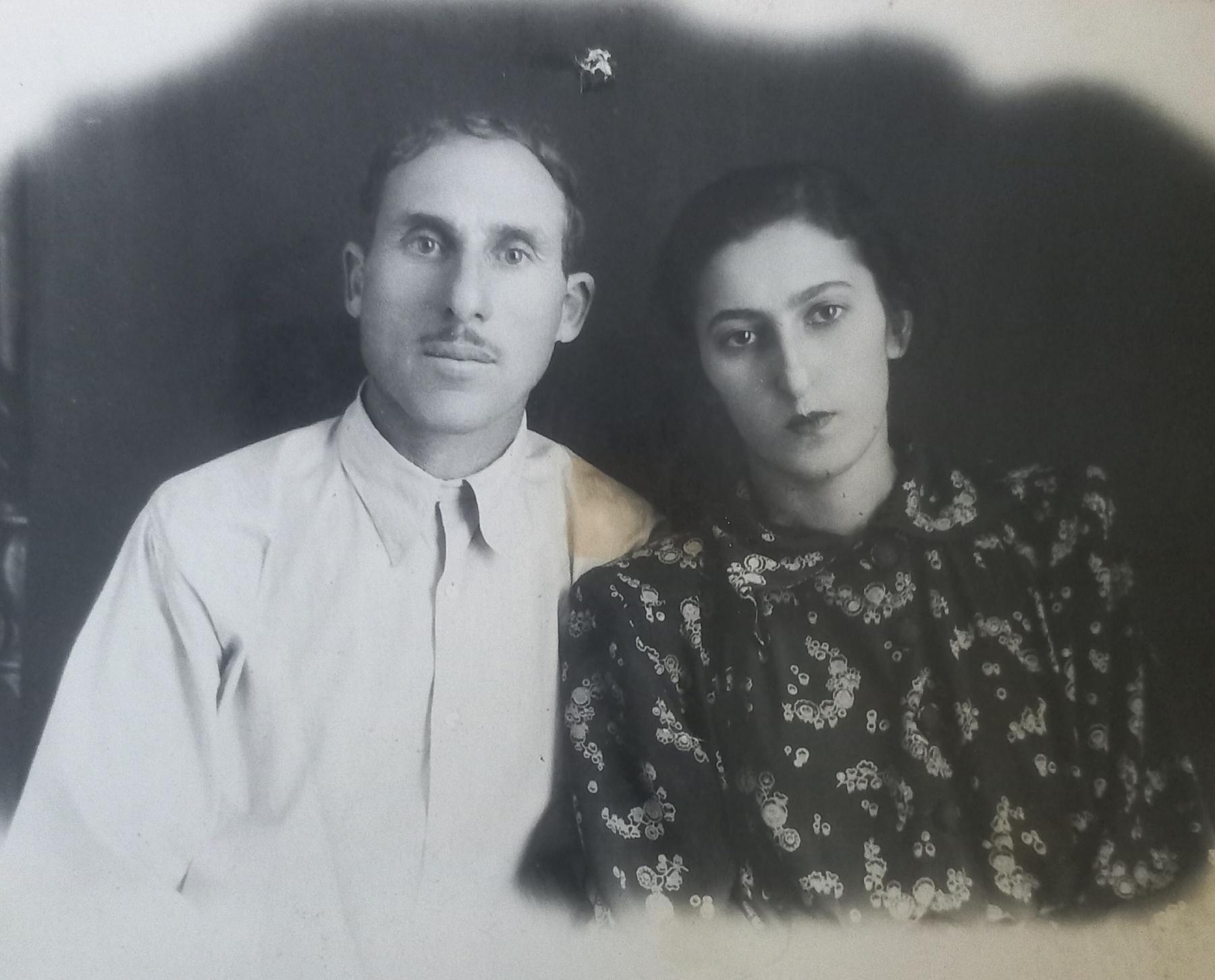

Mom and Dad’s “wedding” photo, Kazakhstan

There were already two boys and three girls in our family, but what did it matter for such a serious decision. They gave it careful thought… Neither my grandmother, Gulnara Zhgenti, was a nobleman’s daughter, nor had my grandfather, Alexander, grown up in luxury or with nannies. But for Iason—who loved our family deeply and had always been loyal—they saw the fulfilment of his long-held dream as a worthy deed and agreed: If a boy was born, Pelago would become his nurse. And so, without his knowledge, the fate of Grisha, that was my father’s name, was decided, which he did not grumble about until he was seven years old, spoilt by the care and love of his foster parents and newfound sisters. The time had come to return to the Kalandadze family. His parents embraced the longed-for boy, while his brothers and sisters kept a distance at first. But his older brother, Shalia, quickly bonded with him. They played together, studied and read together. Despite the difference in age, they had mutual friends and would often gather under a large linden tree in the yard talking, arguing, and exchanging ideas.

Grisha felt that Shalia and his like-minded friends were opposing some prevailing movement. But he was still too young, and his understanding was too limited to fully realise what was happening. His elder brother and his comrades, meanwhile, were in no hurry to involve him in their Federalist passions.

Georgians at the grave of one of the exiled Georgians in Kazakhstan. Kyzylkum 1952 (?)

He was never afraid of challenges. His determination and curiosity were clearly reflected in his passion for sports. He played Leloburti brilliantly, and by the age of fourteen or fifteen, he already had fans across all Guria. But Leloburti6 paled in comparison to the great passion and love that was football. At the time, Poti was the heart and soul of the sport in Georgia. Young and old alike, inspired by the legacy of English sailors and their ‘autograph’ on the game, spoke with awe about this magical sport. It was no surprise, then, that my father fell asleep and woke up dreaming of football.

He enjoyed playing ball with the Chokhatauri boys more than anything, but he knew that there was a completely different football life in Poti, and he felt drawn to it. Besides, he had heard that a guy from Onchiketi (a village in Chokhatauri district), Boris Paichadze, lived in that town, who had barely got off the ground and had already made the whole world crazy with his game. In short, Shalia fulfilled the dream of Gritsko (as brothers and sisters called my father) and took him to Poti. In one of the games my father was released ‘for a trial’ in the match and was even approved. There he got acquainted with Boris, and inspired by their common Chokhatauri origin, they once even ‘showed class’ together, despite my father being six years older than Boria. ‘In a year or two, we’ll take you to the youth national team, but in the meantime, don’t stop training,’ they told my father.

Well, a year passed, then two, three, and four… but Poti and football remained just a dream, and this time, for good… Our family became the focus of a thousand watchful eyes and listening ears. Even a simple trip to the vegetable garden was subject to scrutiny by the so-called guardians of the country’s well-being. The reason? Shalia, who had never accepted the Soviet regime, had emigrated. And what could have kept him in a country where injustice, indifference, betrayal, and cruelty met him at every turn? A country where his father had been killed under mysterious circumstances and where threats were the only response he received when he sought justice?

My aunt Ketevan (Chito) Kalandadze, a famous pediatrician, whose husband was shot in 1937 and who was then deported to Kazakhstan with her two children.

Shalia left for France, and with him, he took my father’s youth, his future, and his dreams… Shalia’s Tail, our relatives and close friends used to call my father affectionately. But that nickname was soon replaced by what is in Russian two devastating words: Enemy of the People. The label clung to his back like a heavy burden for more than twenty years.

The Siberian Gulag camps became his new address. He laboured there, forced to descend into rotting mines. One day, that cursed mine collapsed, but somehow, he crawled out with frostbitten legs (irony of fate, what else could you call it?). He loved life, but he was never allowed to enjoy that love. He survived. He returned. And soon after, he was exiled again, this time to Kazakhstan, along with his mother, sisters, and nephews. The biting cold of Vorkuta was replaced by the scorching heat of the Kyzylkum. Yet not once did he utter a word of reproach toward his brother, who at the time was walking freely through the streets of Paris. None of this, not even the harshest hardship, could overcome the kindness that defined him. And that kindness did not go unnoticed among the exiled Georgians scattered across the deserts of Central Asia, especially by one young woman who had been deported with her parents to a neighbouring kolkhoz.

This was my mother.

Mother especially could not stand two sounds: The loud and forceful ringing of the doorbell, and the clatter and rattle of cutlery. ‘Everyone has their quirks,’ you might have thought, but these were the ‘intrusive’ sounds that disturbed the peace of many families on 25 December, 1951. Yes, in the Varazi Ravine, in the settlement of the Udeli Winery, at midnight, the door of a beautiful red brick house was brought down with banging and the uninterrupted, hysterical ringing of the doorbell by uninvited guests, who came to inform that Alexi Peikrishvili, along with his wife and children, had to appear at the Department to answer a few simple questions.

‘We’ll help you find the documents to expedite the process,’ they said. Since they had to visit somewhere else, they kindly offered to help and started searching through the dresser, wardrobe, cupboard, and cutlery drawer. ‘Oh, we’ll even determine the age of these silverware. Let’s take them with us.’ There was no limit to their kindness.

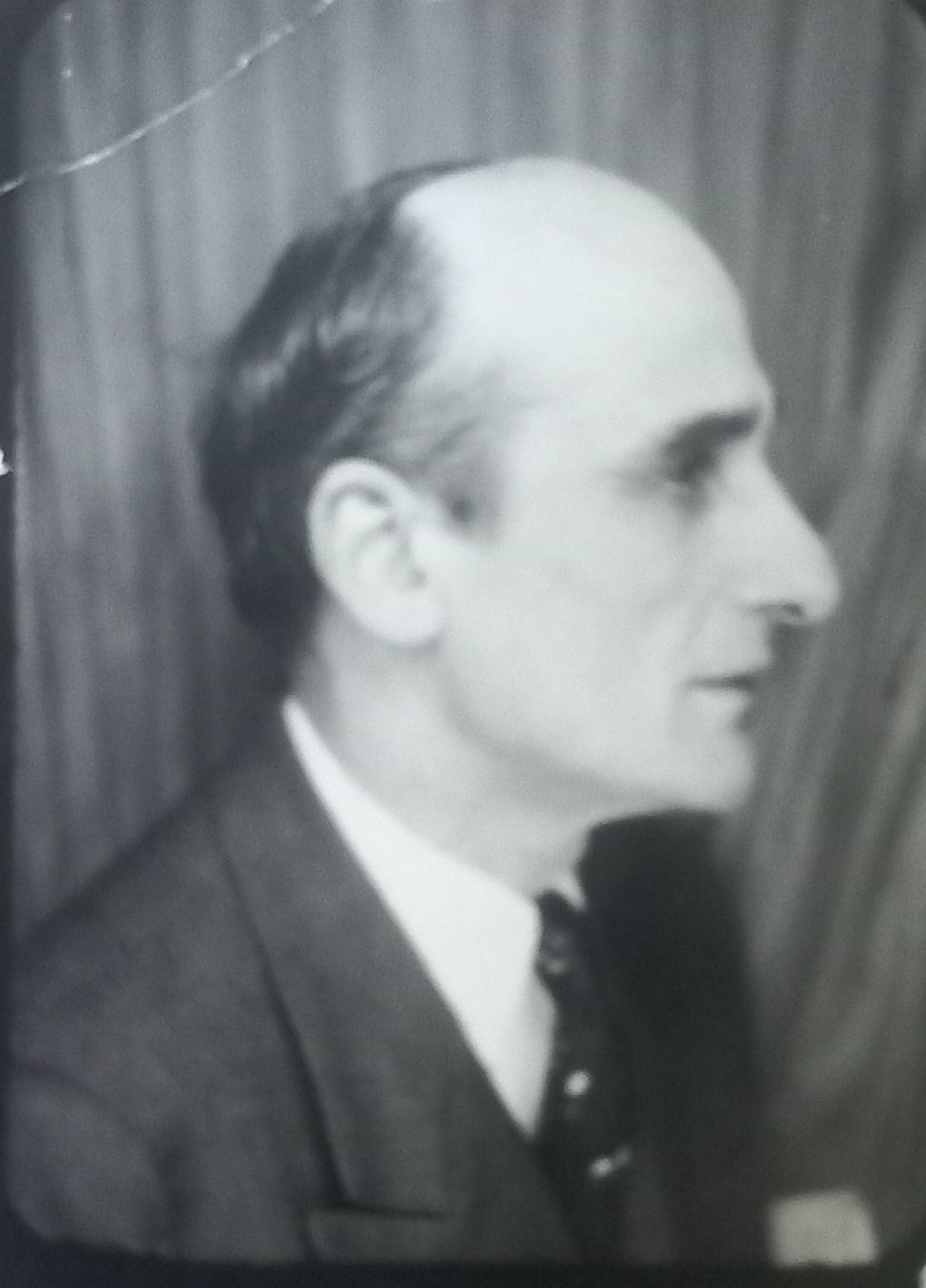

Shalva (Shalia) Kalandadze, whose father was deported to Vorkuta in Siberia due to his emigration to France (13 years apart), and then to Kazakhstan, my grandmother, my older aunt, my younger aunt with two children, and my father again.

The railway station was in complete chaos. The doors of the oily, blackened freight wagons gaped open like the jaws of a monster, greedily devouring the people sacrificed by men in military uniforms of unknown rank. Weeping, dazed, silent, deceived, or bitterly smiling faces vanished behind the doors, which were then slammed shut from the outside.

The train moved heavily, as if burdened by the weight of its cargo. In the carriages, packed with supposed enemies of the people like cattle, sorrowful moans and cries were drowned out by the rumble of the wheels. Mother, grandmother, and grandfather huddled silently in a corner. Even the merciless cold of December could not numb the unbearable pain and insult.

It was a relief to learn that Vakhtang was alive and had started working. His knowledge of German probably made life easier for him there... my mother thought to herself. Deep down, she was even glad that her only brother had not returned—who knows what misfortune might have befallen him after his return from captivity... I worry for my mother and father. How will they endure so much pain and horror? Will this road ever end? Are we to travel forever? Will this damned train ever arrive anywhere...? We’ll see.

Through the cracks in the carriage boards, we caught glimpses of endless stretches of water. Someone said it was the Volga River, and then we passed the Caspian Sea. The train continued to rush steadily eastward.

The development of northern Kazakhstan was a political and economic programme launched after the Second World War. What better solution could the regime of that time have found than the forced resettlement of people to these territories? There were constant labour shortages on the cotton plantations; most of the local population was dying of tuberculosis, so who would willingly choose to live in that hell? So, the enemies of the people and prisoners of war were seen as a godsend.

They lived in a dugout. Water was drawn from a canal where camels and donkeys came to cool their sand-scorched hooves—and, naturally, to relieve themselves. This putrid water was used by the locals to wash everything they owned, disgusting as it was. And they had to drink it too, boiling it several times over. For that, they needed firewood, which could only be bought at the bazaar in the neighbouring village. But to get there, they had to walk several kilometres across a desert crawling with snakes.

My mother Keto Peikrishvili in Kazakhstan, 1951.

Once, a young man with green eyes helped her fetch firewood. He had a limp in his right leg, but that didn’t stop him from carrying a heavy load. He was invited home as a gesture of thanks for helping their daughter. But before long, he excused himself, citing the approaching darkness, and set off toward his settlement with a heavy heart. All the way, he was tormented by a single thought—how to get this quiet, timid girl out of that terrible dugout. Her sad face had long haunted him. Then, one day, he heard that the school was looking for a Russian language teacher…

The job was followed by a move to a ‘better’ settlement.

‘May your joys be as deep as your sorrows,’ said a Georgian, and they continued to live by that proverb.

Vakhtang Peikrishvili, my mother’s brother, who was deported to Kazakhstan due to emigration to Germany. My grandmother, grandfather, and mother are buried in Bavaria.

‘That guy’ was happy, too, now that ‘that girl’ lived closer to him. Soon, in their shared archive—alongside ‘Vrag Naroda ’ and a thousand other vile documents—an important and auspicious document appeared:

‘Неке туралы куәлік’—a Kazakh marriage certificate. Written in Russian with a pen dipped in an inkpot, it read:

Kalandadze Grigory Aleksandrovich.

Peikrishvili Guguli Alekseevna.

Actually, her name was Ketevan. She was used to both names and didn’t particularly bother to correct it—she had far more serious concerns at the time. Who would worry about such trivialities in that situation, anyway? As my mother used to say, ‘Even if I had seven names, they would not make me renounce my Georgian identity or take away my love for my country.’

My mother and father even managed to have a ‘wedding’ while in exile in Kazakhstan, and my grandmother somehow found a way to give her daughter-in-law a gold brooch (this brooch, set with a fiery opal from the Pamir Mountains, is now mine—I cherish it like the apple of my eye). In short, those united by a shared misfortune became one large family, adding nine repressed souls to my biography: my grandmother (my father’s mother), two aunts (one of whose husband had been shot in ‘37), two cousins, my grandparents on my mother’s side, and of course, my mother and father—who, thanks to the cursed purges of 1937, had already spent thirteen years in exile in the farthest reaches of the country, a place called Siberia. As for my grandfather, who was ‘accidentally’ killed in Trabzon... well, let’s just say no more.

All right now, what are you so surprised about? Those were the times back then!

1. Zhgenti — A Georgian family name

2. Krimanchuli — A distinctively flowing, thin, high voice in Georgian polyphonic singing

3. Gurian — A native of Guria, a region in western Georgia known for its vibrant culture, quick-witted and humorous people. Gurians are often characterized in literature and folklore as sharp-tongued, spirited, and deeply kind-hearted.

4. Oda – A traditional wooden house common in western Georgia, especially in regions like Guria and Samegrelo.

5. Odesa – A type of wine traditionally produced in the Guria region of western Georgia, made from a specific local grape variety. Known for its distinctive flavor, Odesa is often aged in clay vessels (kvevris), which enhance its aroma and character.

6. Leloburti – A traditional Georgian ball game, often compared to rugby, played primarily during festivals.