Author : Gigi Gigineishvili

In Abkhazia, five kilometres from Gudauta and just fifty metres above sea level, lies the village of Likhni (Abkhaz: Лыхны). At its centre stands the 10th-century cross-domed Church of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary, where numerous fascinating Georgian inscriptions have been preserved. Among them is one of particular interest—the inscription, “On the Appearance of the Comet”. Although well known to Georgian historians, this inscription is not widely known to the general public.

This is a one-line inscription, executed in a distinctive and aesthetically refined manner: The initial letter of each word is written in the Asomtavruli script1 and is enlarged, while the remaining letters of each word are smaller and extended horizontally. The script features rounded forms, and in some cases—such as the letter ან—smaller letters are inscribed within the “belly” of the larger letter. The entire inscription is rendered in red cinnabar pigment. The text reads as follows:

„Ⴕ. Ⴉურთხეულ Ⴞარ, Ⴖმერთო, Ⴗოვლად Ⴗოველსა Ⴘინა. ႤႱ Ⴈქმნა Ⴃასაბამითგან Ⴜელთა ႾႵჂႧ (ხქჲთ — 1065 წ.), Ⴕორონიკონსა ႱႥႮ (სვპ — 1066 წ.) Ⴋეფობასა Ⴁაგრატ Ⴂიორგის Ⴛისასა Ⴈნდიკტიონსა ႪჁ (ლჱ), Ⴀპრილსა Ⴇვესა Ⴅარსკვლავი Ⴂამოჩნდა, Ⴐომელ Ⴋისსა Ⴜიაღსა Ⴀღმოლიდის Ⴃა Ⴜინა Ⴋისსა Ⴅითარცა Ⴘარავანდედი Ⴃიდი, Ⴋოკიდებით Ⴋასვეა. Ⴄსე Ⴈქმნა Ⴁზობითგან Ⴀღვსებამდის.“

“Blessed art Thou, O Lord, in all things. In the year 1066 from the creation of the world, in the 38th year of the reign of Bagrat, son of Giorgi, in the month of April, a star appeared—rising from the depths and going before him, surrounded by a great radiance that touched it. This occurred in the period from Palm Sunday to Easter.”

Halley’s Comet inscription, 1886.

In 1848, the inscription was first studied by the academician Marie Brosset. It is believed that the inscription in the Church of the Dormition in Likhni describes one of the appearances of Halley’s Comet within the Earth’s visible sphere, which occurred in 1066. Based on the beginning and duration of Bagrat IV’s reign, the dating corresponds to 1065, while the astronomical chronology points to 1066. The text states that the comet appeared in April, from Palm Sunday to Easter (in 1066, Easter fell on 16 April, making Palm Sunday 9 April), thus the date of the inscription should be considered as 1066. Accordingly, the comet was observed in Georgia between 9 and 16 April of that year.

Other Georgian inscriptions can also be found on the Likhni Church: the inscription of Vache the Protospatharios and Peter the Patrician; the inscription of Giorgi Kuropalates; as well as about ten inscription fragments dating back to the 11th century. Additionally, more than ten inscriptions from the 14th century accompany the frescoes of that period, identifying the figures and scenes depicted.

The Likhni inscriptions are among the most important sources for the history of Georgia, though much transpired later in Abkhazia, and likely many comets have since passed by. As Vakhushti Batonishvili2 reported in the 18th century, “There was a great plague in Odishi, as we have described, and it came particularly from the Abkhazians, for they came by boat and by land, capturing and settling as far as the River Egrisi, and there were no more bishops of Dranda and Mokvi.” The situation turned bitter for Georgia due to internal wars and the actions of traitors within the country.

On 18 March 1989, in the village of Likhni, Abkhazians no longer wrote inscriptions about Halley’s Comet or Giorgi Kuropalates, but about secession from the Soviet Republic of Georgia and unification with Russia, and those inscriptions they wrote in the Russian language.

18.03.1989. Village of Likhni

In parallel with the revival of the national movement in Soviet Georgia, the Abkhaz People’s Forum—Aidgylara (Abk. Aԥsny Zhalar Rforum ‘Aidgylara’—Unity) was established in Abkhazia with the support of the Russian security services. It was a socio-political movement founded on 13 December 1988 as an Abkhazian nationalist movement. In the initial stage, Aidgylara’s main function was to show Georgian communists and ‘informals’ the threat of Abkhazia’s secession and, in general, to make Abkhazia a deterrent to the Georgian national movement, but later it was assigned other, more destructive tasks. ‘Aidgylara differed from other similar organisations (except for Adamon Nykhas, which was established in South Ossetia by the Russian security services in the same period) in that party workers, officials, police, and security officers of Abkhazian origin represented the real, albeit shadowy, driving core of the organisation. It was on the initiative of Aidgylara that on 18 March 1989 a congress of thousands of Abkhazians was held in the village of Likhni.

The rally was officially authorised—a rare occurrence for such gatherings under the Soviet system. Notably, it was attended by the entire Abkhaz segment of the party elite of the Abkhaz Autonomous Republic.

18.03.1989. Village of Likhni

The meeting adopted a document known as the Likhni Appeal, which was sent to Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and other top Soviet officials. In recent years, this fact—and the document itself—has been filtered through layers of Russian disinformation and presented to Georgian society in a distorted form. It is important to set the record straight: The claim that the Abkhaz population allegedly demanded independence at Likhni is far from the truth. In reality, the authors of the Likhni Appeal clearly called for remaining within the Russian Soviet empire.

Such demands were not isolated. Prior to the Likhni Appeal, a similar letter from the Abkhaz ‘red intelligentsia’, dated 17 June 1987, was sent to Moscow with nearly identical content. Later, on 23 March 1993, the Abkhaz delegation of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia sent another appeal to the Russian Duma, requesting the annexation of Abkhazia into the Russian Federation—under any form that Russia deemed beneficial. In addition to the Likhni Appeal, Aidgylara actively participated in the 17 March 1991, referendum aimed at preserving the Soviet Union and promoted loyalty to Leninist ideals within Abkhaz society—not the idea of freedom, as it is often misleadingly portrayed today.

The text of the appeal consisted of the following main demands:

1. To approve the letter addressed to the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Mikhail Gorbachev and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR Nikolai Ryzhkov;

2. To request that the Supreme Soviet and the Council of Ministers of the USSR restore the status of the Abkhaz Soviet Socialist Republic in the form it held during the Leninist era;

3. To reconsider all transformations that had constituted a gross deviation from principles of national equality in the USSR.

On 24 March of the same year, the Likhni Appeal was published in Sovetskaya Abkhazia and other regional newspapers of Abkhazia, including the newspaper Bzip.

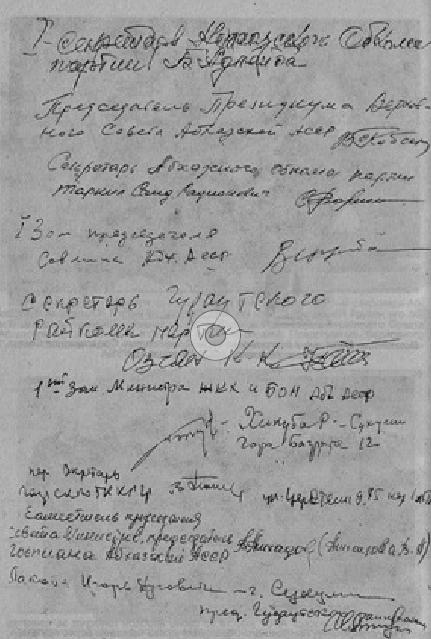

Signatures of the Soviet elite of Abkhazia on the appeal of 18.03.1989.

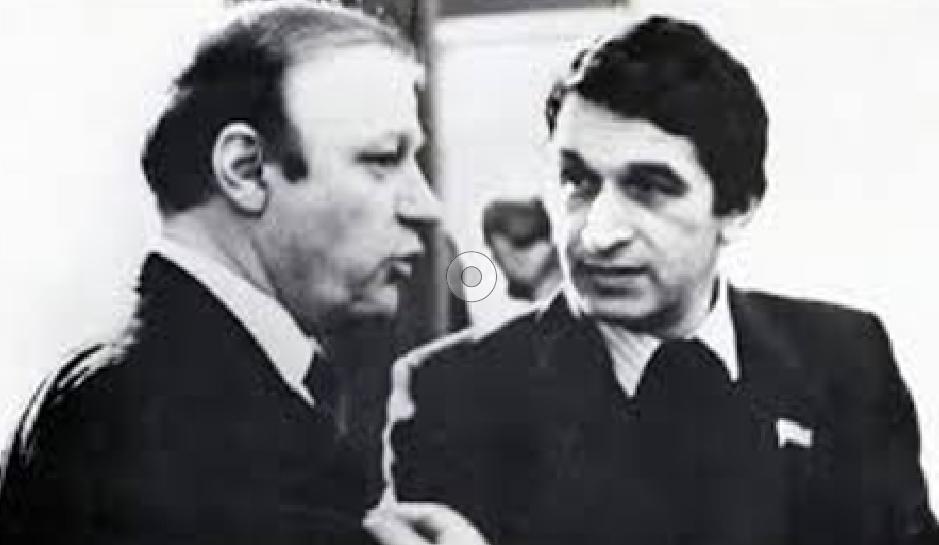

The Likhni Appeal was signed by: Boris Adleiba, First Secretary of the Abkhazian Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia, Member of the Supreme Council of the USSR, Member of the Abkhazian Regional Committee Bureau; Valerian Kobakhia, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Abkhaz ASSR, Member of the Supreme Council of the Georgian SSR, Member of the Abkhazian Regional Committee Bureau; Konstantin Ozgan, Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Abkhaz ASSR, Member of the Supreme Council of the Abkhaz ASSR, First Secretary of the Gudauta District Party Committee; Alexander Gvaramia, Rector of the Abkhaz State University, candidate for People’s Parliamentary Deputy of the USSR; and others. It was the signature of the latter that caused particular resentment among Georgian students at Sukhumi University, as Georgian students felt special affection for Aleko Gvaramia and it was from him that they could not bear this signature, which was seen as a betrayal.

The appeal was accompanied by the signatures of over 30,000 people of various nationalities—Abkhazians, Georgians, Russians, Armenians, Greeks, and others. Beginning on 19 March, information about the appeal was relayed directly to Georgian communist officials from Moscow, often with threatening undertones and veiled warnings. The content of the appeal sparked widespread outrage in Tbilisi, Gagra, Sukhumi, Gali, Kutaisi, Zugdidi, and other cities across Georgia. Protests and demonstrations erupted. Georgian students at Sukhumi University refused to continue their studies and, among other demands, called for the resignation of the rector, Alexander Gvaramia.

Few in Georgian society remember that it was the Likhni Appeal that set in motion the chain of events leading to the tragedy of 9 April, 1989. Protests against the appeal began in Tbilisi in March of that year, but starting from 4 April, they became more organized and soon evolved into broader anti-Soviet demonstrations.

A. Gvaramia and V. Ardzinba

Moscow responded to these demonstrations again: on 9 April 1989, at dawn, Soviet airborne units, including the 345th Independent Guards Airborne Regiment, deployed in Tbilisi, surrounded peaceful demonstrators and violently dispersed them using sapper spades and toxic gas. The brutal crackdown resulted in the deaths of twenty-one civilians—most of them women—and left hundreds more injured. This tragic event became a pivotal moment in Georgia’s struggle for independence from the Soviet Union.

In response to the barbaric actions of 9 April 1989, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Council of Ministers of the USSR issued a statement attributing the incident to ‘riots provoked by extremist, anti-social elements.’ They claimed that during the suppression of these riots in Tbilisi, a number of people, including civilians and military personnel, were injured, stressing that none of them had cut or stab wounds. This statement was an example of the traditional Soviet tactic of deflecting blame by blaming the violent deaths of people on the Georgian side.

At that time, Georgian society was unaware that the Likhni Appeal was merely the initial phase of a broader conspiracy against Georgia—a catalyst that triggered a series of devastating events orchestrated by Russia.