Author : David Bukhrikidze

Thirty years have passed since the collapse of the USSR, and yet the bitter experience of the post-Soviet period – wars, economic, religious, and cultural alienation – constantly makes us think not only about the psychological traces of the terminated Soviet empire, but also about the historical, declared, or potential threat coming from Russia today and in the future.

The entire history of Russian-Georgian relations is full of negative “memory cards”, starting with the manifesto issued by Pavel I on abolishing the Kingdom of Kartli and Kakheti (which effectively ended the independence of Georgia) after the death of the last King of Georgia, Giorgi XII, in February 1801. It continued with the Red Army's occupation in February 1921 and ending with a bloody crackdown on peaceful demonstrators in front of the Parliament building on April 9, 1989 – which would formally herald the collapse of the empire.

The nearly two-hundred-year occupation, which as the classical poet [SB1] said “brought much blood and tears”, slowly and with great difficulty taught us the ways of regaining Georgia's independence and living with new awareness and hardships after gaining it. However, the colony-metropolis paradigm is full of historical traumas and dramatic mistakes and is much more nuanced, reflected in spheres of significant influence: economy, religion, language, and culture.

Obviously, it is impossible to discuss and analyze everything in one article. We shall therefore focus on the most fragile and, as my contemporary poet would say, “mined with perverted sophistication” culture, which proved to be the most flexible and indeed perverse form of the empire's soft power. However, language coupled with culture (Russian, as the mandatory language and language of communication of the Soviet era) is no less influential and takes on a negative meaning today, especially against the backdrop of the Russian-Ukrainian war. Nevertheless, the negative-language or negative-cultural context is still an instrument of politics.

If we travel back in time and look at the cultural kaleidoscope of the Soviet era, we will discover many important details that will give us a fuller picture, or gestalt. Our socialist past, all those trips to the cinemas and the theatres, the 37-ruble flights to Moscow, the MKHAT, the Lubimovka, the Bolshoi, the Tretyakovka or the Dom Kino (cinema house), plus the not-so-naive gastronomic – sensual – sexual appeal, created the illusion that Georgians were almost the most attractive and exotic sex toys of the Soviet system. Moreover, these pseudo-attitudes (prejudices) were formed over decades under the influence of sincere expectations and naïve perceptions of the nation.

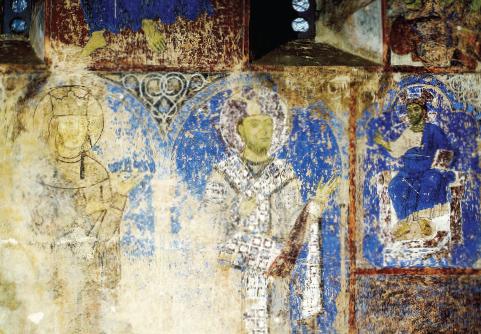

If we leave aside Soviet-era cultural contacts and all sorts of fondness of Bella Akhmadulina-Otar Chiladze type constructed with the sincerity of the early Christian era, we will find out that the Russian-Georgian “magnetic attraction” was most likely fueled by historical experience, cultural archetypes and orthodoxy... starting from the nineteenth century when Garsevan Chavchavadze and Grigol Orbeliani became real representatives of the Russian Empire in Georgia, while the marriage of Nino Chavchavadze and Alexander Griboedov was actually concluded as a political mesalliance, Russia completely conquered the political, religious, and cultural spheres in Georgia. The figure of Griboedov is a separate subject of research as details of his assassination in Tehran and his role in the security service of the then Russian Empire are still classified.

Behind corruption schemes in the 70s and 80s of the last century, a commendable cultural tradition was visible too, so much so that Georgian intellectuals set records in the number of theses defended in Moscow (although our neighbors, Armenians and Azeris, were not far behind either). Friendship+corruption+nepotism+pseudo-orthodoxy – this was roughly the mechanism of the USSR of the last century, which despite the anti-corruption and educational reforms of the Rose Revolution, the Georgian Dream government revived like an extinct archaeopteryx.

The paradox is that for most of the population living in Russia, Mimino is still a collective face of a Georgian, acceptable and natural. The image of a Georgian, leftover from Giorgi Danelia's popular film and Buba Kikabidze's hero, will probably not disappear from Russian consciousness for decades to come.

It is unfortunate that such an anti-Putinist fighter as, for example, film director Dmitry Krymov (the son of the famous director Anatoly Efros and theatre critic Natalia Krymova), who has visited Tbilisi very often since childhood and today is practically exiled from Russia, is unable to free himself from erroneous and schematic attitudes.

In the new production Everything is Here (2022), inspired by Mikhail Tumanishvili's “Our Small Town”, the Georgian is still portrayed as a stupid, pot-bellied, hairy, unreasonably arrogant and childish creature, who has never managed to learn Russian and tries to flaunt his pointless stupidity in every possible way. Well, what can one demand from an ordinary Russian (who has recently mastered the streets of Tbilisi to perfection), when even the famous director himself is unable to focus on reality.

Post-Soviet Russian cultural sentiments about Georgia have not disappeared from their consciousness. A Russian citizen still associates every possible and impossible image with wine, khachapuri, dancing and partying, and sometimes with Pirosmani. Probably those who come here for entertainment will be dissatisfied if they do not find this standard icon in Georgia. A separate issue is the different types of Russian language and culture centers in Georgia, and especially the Russian Club, which is not only an expression of “soft power”, but is also directly driven by open political messages from Moscow. However, the authorities do not respond to this fact in any way, instead they encourage a disgusting campaign “Gareji is Georgia”, which fits directly into the Kremlin's geopolitical narrative.

Another “weird” event of 2022 was the participation of the film studio Georgian Film in the alliance of film studios of the CIS countries. The decision to create this alliance was made at a forum of the CIS countries and Georgian Film Studios' Board of Directors, which was held online in the capital of Tajikistan, Dushanbe. An agreement on cooperation in the field of cinema was signed between representatives of various film companies and studios.

If it were not for the information published in the Russian and Uzbek press, nobody in Georgia would have known about it. Only after this fact became public, the members of the Board of Directors of Georgian Film released a statement on a social network. If one considers that holding the forum in Dushanbe and restoring creative ties in the post-Soviet space is first of all in the interest of Russia, everything becomes clear. The main figure among the forum participants is film director Karen Shakhnazarov, general director of Mosfilm Concern, one of Putin's active supporters, and a regular participant in Solovyov's political talk shows.

Clearly, Russia's culturally impregnated soft power presents a particular challenge in the context of the EU and Georgia. Russia actively uses the economic, political, informational and cultural leverages at its disposal as a weapon to achieve its geopolitical goals. The Kremlin is particularly active in the countries that are loyal to Russia or see themselves in its sphere of cultural influence. The Kremlin's propaganda and disinformation campaign poses a real threat to Georgia, especially against the backdrop of the Russian-Ukrainian war.