Author : David Khvadagiani

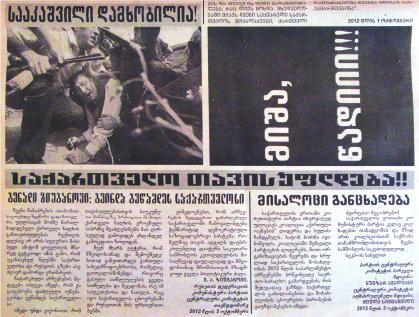

A few years ago, in my village in Racha, I accidentally found a scrap of a ten-year-old newspaper with no date or cover, although I easily understood that it was one of the 2012 or 2013 issues of the Asaval-Dasavali newspaper.

The remaining piece informed readers that “Saakashvili has been overthrown” and “Georgia has been liberated”. Below this text, with the enlarged headlines and the manipulated picture out of context, the Chairman of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation Gennady Zyuganov and the leaders of the United Communist Party of Georgia, absolutely unknown and unidentifiable to the public, congratulated the Georgian Dream coalition and its leader Bidzina Ivanishvili on their “brilliant popular victory” and expressed hope that all political forces would take their place in a “renewed Georgia” under conditions of peaceful labor and prosperity.

Ten years ago it was almost impossible for a significant part of society, deceived by Russian propaganda, to notice dangerous symptoms – the complete overlap between the worldview of the Communist Party, a remnant of the Russian imperial past, and a new political force that had come to power – and to discern their linkages. The active part of society opposed to the government of President Saakashvili and the then ruling United National Movement political party perceived such anomalies as frivolous. They persisted in convincing themselves and their opponents that the coming to power of a Russian oligarch and the expected change in the foreign policy vector was a political manipulation and an attempt to create a sham reality. However, the difficult and destructive political process that has unfolded over the past decade has repeatedly shown us the pernicious influence of Russia on the ruling political party that came to power, and has prompted an informed section of society to look for parallels with events of the recent past. But clarifying the processes of the past and discerning the logical chain linking it to present-day events has been difficult due to the ignorance of important historical and political processes that have been deliberately pulled out of the Georgian society’s collective memory over the decades.

Georgia and Russia

Almost two and a half centuries of Russian-Georgian relations unfolded against the backdrop of the most significant events in the history of mankind. The beginning of the 19th century, when the expanding Russian Empire was conquering and annexing one Georgian kingdom after another, coincided with the peak of the development of big empires. The empire, according to international law and the political system of the time, had a completely legal right and means to conquer and annex small nations and to abolish signs of their sovereignty and statehood. In the first half of the 19th century, the numerous attempts by the Georgian royal family and elite to shake off Russian influence failed and ended in repressions and the destruction of its fighting force, which was left face-to-face with the mighty empire. In the second half of the 19th century, when Russia finally consolidated its position in the Caucasus, the struggle for the preservation of Georgian identity and self-government began to develop through the activities of Georgian educators and social movements. However, the struggle of the active Georgian society and political parties that emerged at the end of the 19th century – for even a limited local self-government and political autonomy – ran blind into a wall erected by the Russian imperial government. In 1905-1906 revolutionary processes were ongoing throughout the entire Russian Empire, and contributed to much of the active development in Georgia, although the reaction of the Russian authorities was harsh and ruthless, which brought very serious consequences.

The seemingly hopeless and desperate situation was changed by one of the biggest and most dramatic events in the history of mankind. The great war that began in 1914, which was then called by various epithets such as the “International War”, “Industrial War”, and is now known as the First World War, completely changed the political map of Europe, especially its eastern part, as well as the course of world history. The war, which brought unimaginable human casualties and the destruction of the infrastructure and economy of all of Europe, also put an end to the era of great empires and opened a historical window and opportunity for freedom for small conquered nations, including Georgia. Despite decades of disinformation and myths propagated by Soviet propaganda, the Georgian political elite met that historic opportunity prepared. At that time there were four strong political parties in Georgia, which had the experience of almost two decades of political struggle:

● The largest and most popular Social-Democratic Party, which after a split as a result of the processes unfolding in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, unlike Russia, left the Bolsheviks in a marginal minority and fully adopted the so-called Menshevik views when their leader Noe Zhordania returned to Georgia in the early twentieth century. He had been studying and traveling in Europe and opted for a European social democratic platform in opposition to the backward Russian “narodnik” platform.

● The Social-Federalist Party, which was created in Geneva in 1904 by a group of Georgian nationalists, raised the issue of political independence and freedom of Georgia for the first time.

● The Party of Social Revolutionaries, which, unlike its popular Russian counterpart, had little support in Georgia

● The National Democratic Party, which was created in 1917 by the union of various nationalist groups.

Shortly after the Russian February Revolution of 1917, following the civil war and the Bolshevik coup that began on the ruins of the empire, the Social Democratic Party in power in Transcaucasia, which found itself amid the disastrous processes that had emerged on the ruins of the Ottoman and Russian empires, intended to position itself in the new political process by seceding from Russia, creating a Transcaucasian Federal Democratic Republic and trying to control the Baku-Batumi strategic highway, which led to the first confrontation and bloody clash with the Transcaucasian Bolshevik Organization. On February 10, 1918, the opening day of the Transcaucasian Sejm, local Bolsheviks sharply criticized the secession of the Transcaucasus from Russia with a protest demonstration, leading to their persecution by the authorities and several casualties. In the following decades this story became a landmark event for Soviet propaganda.

On May 26, 1918 the collapse of the Transcaucasian Federative Democratic Republic, caused mainly by the mutual incompatibility and permanent conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, led to the state independence of Georgia. Georgia's reformist government and political opposition, which agreed to the main rule of the game that Georgia should be an independent, sovereign, and democratic republic, brought great success to the newly established modern state. Equal elections of city and local self-governments were held, in which all Georgian citizens, regardless of gender, ethnicity or religious affiliation, had the right to fully participate. In the national elections, a woman from Karayazi became the first Muslim woman in the world to ever be elected as an MP, winning a seat on the Tbilisi Constituent Assembly. In February 1919, elections to the Constituent Assembly were held, in which the Social Democratic Party won and five women MPs were elected to the multi-party Constituent Assembly, which was a very progressive event globally at the time. For the first time judicial reform was carried out and the institution of jury trials was established. Agrarian reform and other reforms were carried out, creating a solid foundation for the existence of the newly established independent, democratic state of Georgia. The newly created state, with its regular army, people's guard, and special services, was able to repel direct attacks both by the Russian volunteer army in 1919 and an attack by the Red Army of the Soviet Union after it had won the Russian Civil War in 1920 and occupied the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan. The Georgian authorities managed to eliminate several Bolshevik uprisings and prevent Russian provocations, but in the full-scale Russian-Georgian War of February-March 1921, which lasted almost six weeks, Georgia was defeated and the authorities who, despite the efforts of the occupation government, did not capitulate or legally hand over power to the aggressor, had to go into exile.

The Era of Breathing Freely

“After three years of being in shackles, the workers and peasants of Georgia were freed from the tyranny of the treacherous Mensheviks. On February 25, a red flag flew over the Georgian capital. On February 25, the long-suffering and oppressed workers breathed freely for the first time.”

This is how The Communist newspaper announced the arrival of a new reality to half of Georgia in one of its first issues on March 4, 1921, when the occupying Red Army of Soviet Russia entered the capital of Georgia.

In the middle of March 1921, the last battle between the troops of Georgia and Soviet Russia took place on the outskirts of Guria. At that time the Revolutionary Committee, which again arrived in Tbilisi summoned several members of the Constituent Assembly who had remained in the capital to the Palace of the Constituent Assembly of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. They were asked to mediate negotiations with the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, which had relocated to Western Georgia. Upon leaving the palace, Geronti Kikodze, a member of the Constituent Assembly, witnessed the first step of the new information and propaganda policy of the self-proclaimed government: “... We saw photographs of mutilated corpses displayed on a large board, an illustration of the violence that the Menshevik Guards and militiamen used against Communists, a clear call for revenge.”

On April 11, 1921, the Chairman of the Georgian Revolutionary Committee Filipe Makharadze arrived in “liberated” Kutaisi and the Chairman of the Kutaisi Revolutionary Committee David Lortkipanidze and local Bolsheviks showed him photos of the burnt bodies of famous Bolshevik terrorist Pavle Mardaleishvili and the Soviet Russian intelligence agent, Colonel Nikoloz Ivanov, “tortured and murdered by the Mensheviks”.

“’The twelfth-century Inquisition is nothing compared to this, just nothing!’ said Comrade Filipe in a low voice,” reported The Communist newspaper.

The Chairman of the Georgian Revolutionary Committee did not miss the significance of such evidence, which would “hang on a pillar of shame” their political opponents and told his fellow party members that such materials could not be left “behind closed doors” and ordered the photos to be enlarged and posted in the streets so that people could see the “butchery of the Menshevik inquisitors”. Makharadze's order was immediately carried out and enlarged photographs of the dead Bolsheviks were displayed for months on the main streets of Kutaisi and Tbilisi.

The Ivanov-Mardaleishvili case was the first and most powerful propaganda action of the occupational government behind which in fact was an episode of the tough and ruthless struggle between independent Georgia and the security services of Soviet Russia, although Georgian Bolsheviks for a long time portrayed the dead as “innocent victims” of the brutality of the former authorities who suffered only for political reasons.

After the occupation, from 1921 to 1924, anti-Soviet uprisings were declared “a Menshevik venture and revenge organized from abroad with the help of European capitalists”, and the exiled government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia the “restless enemy of the Georgian people”. The Government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia was accused by the Bolshevik propaganda of the following:

· Secession of Georgia from Russia;

· Selling the country to Western capitalists;

· Intention to hand Adjara over to Turkey;

· Launch of war with Soviet Russia;

· Bringing in troops from foreign countries;

· Theft of Georgia's national treasures.

Most importantly, they were declared “butchers of Georgian workers and peasants”, for the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia brutally suppressed a number of Bolshevik uprisings financed and organized by Soviet Russia, and arrested or expelled many “agents bribed with Moscow gold”.

Also of interest is the recollection of Geronti Kikodze when he met Mamia Orakhelashvili, a member of the Revolutionary Committee of Georgia, in the former Palace of the Constituent Assembly, and Orakhelashvili accused the Chairman of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia Noe Zhordania of waging war with Soviet Russia:

"So many healthy young men died due to Noe Zhordania's reckless policies. When I looked into the trenches of Kojori and saw the corpses of beardless soldiers and cadets, my heart nearly broke," Orakhelashvili told Kikodze.

Never-Ending Occupation

In the 1920s and 30s, amidst the resistance front in occupied Georgia, the destruction of political opponents, and the devastating results of World War II, a complete information vacuum and the concept of Georgian independence, as well as elements of a free political and public culture, finally disappeared from the memory of the new generations born in Soviet Georgia.

Following the processes unfolding in the late 1980s, the collapse of the Soviet Russian Empire, and the restoration of Georgia's state independence on April 9, 1991, the legitimate government of independent Georgia and the first President Gamsakhurdia faced exactly the same challenges and reactionary Russian revenge that were taking place almost a century earlier. However, unlike the Tsarist Russia, the political leaders, who grew up under total pressure and closed doors in Soviet Russia, for a long time did not find the ability to struggle. Resistance, followed by a military coup, was organized from Moscow and supported by the Transcaucasian Military District, overthrowing the legitimate government and president.

On January 8, 1992, after an armed coup organized by Russia, the newspaper The Republic of Georgia, on behalf of the so-called military council and similar to the events of seventy years ago, announced in its January 8 issue that “a dictatorial regime was overthrown” and that it had manipulated the people in the name of “freedom”. Similar to the Soviet-Russian occupation, which for a long time claimed that Soviet Russia had nothing to do with it and that the “despotic Menshevik government” was overthrown by Georgian workers and peasants, the illegitimate and military coup government also denied any connection to Russia for almost the entire 1990s and presented itself as “a response to the destructive actions” of President Gamsakhurdia.

Although President Shevardnadze reversed his pro-Russian course from the second half of the 1990s and took the first steps towards integration with the West, Georgia remained a non-existent and failed country. The situation changed dramatically with the peaceful Rose Revolution of 2003, which brought to power a reformist team that made Georgia's sovereign rights a reality. Along with making reforms, it started to get rid of Russian influence and made integration into Western structures a viable option. This was followed by Russian aggression and full-scale war in 2008. Despite the fact that the Georgian armed forces managed to resist, which was soon followed by the reaction of the West, the suspension of the war, and Russia’s failure to achieve its main goals of seizing the Georgian capital, destroying the political government, and establishing a proxy regime. A few years later the Russian hybrid war machine, financial support, and the concentration and pressure of a large number of military forces around Georgia, along with some other factors and conditions of an external environment, brought to power in Georgia the political team of Russian oligarch Ivanishvili. After 2012, it took decisive steps to hinder Georgia's integration with the West and again linked Georgia closely to Russian influence in economic and political terms.

Based upon the tragic experiences of the Georgian history of the last century, the Georgian Dream government also began to actively persecute and demonize the previous government. It is important that after the foundation of the modern state of Georgia was laid on May 26, 1918, its three prominent political figures, Noe Zhordania, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, and Mikhail Saakashvili, despite their ideological and political differences, were moving in the same direction in the main and most important issue: Getting rid of Russian influence and developing a separate political agenda. The reaction of the Russian imperial policy to all three of them was one and the same. Noe Zhordania was expelled from Georgia by the Russian occupation army and died in exile. Zviad Gamsakhurdia was first expelled by a military coup organized from Moscow and then physically liquidated under unclear circumstances. Mikheil Saakashvili, who was forced to flee Georgia due to political persecution after Russian-influenced groups came to power and returned to his home country illegally years later, was arrested on absurd charges and his life and health are still in danger.

The attacks of Russia on Ukraine in recent months, its occupation and its attempts to restore its empire have not achieved their goal. The Ukrainian Armed Forces have not only succeeded in repelling the attack at the capital city of Kyiv, but have launched a counter-offensive and are methodically liberating the Russian-occupied sovereign territories of Ukraine. The heavy losses of the Russian army and Western sanctions have raised hopes that the failure of the historically-experienced-in-big-wars Russian military machine will lead to the final collapse of the empire, and that the countries under its influence and occupation will gain freedom forever.