Author : Keti Kurdovanidze

If we say that time has the highest price today, we would not be mistaken, because we want to manage everything, although sometimes we don’t even know what that “everything” is. The fact is that there is nothing vital here, because we exist perfectly well without it, and we do not deprive ourselves of particularly enjoyable activities, because we always find time for them. However, we are invariably good at one thing: Looking into our smartphones at every peep, finding out who is texting us or making suggestions, and then using the “delete button” to erase forever the accumulated useless information of our lives. But what we read is still involuntarily remembered, regardless of whether we will ever use the information or not.

If a short text message is so impressive, imagine how it works when it comes to the opinion of influential, nominated or recognized individuals, especially as we purposely try to remember it so that we can use it later to show off.

However, the memory is characterized by the ability to remember only subjectively, so our space is gradually filled with a thousand interpreted bits of information, and therefore, coping with it requires much more time. Since we don't have this time, we start using the delete button to free up space. So, what do we delete and what do we leave?

We delete what we have re-evaluated, that is, we forget what we once defended fiercely. We give free space to something that grips us even more strongly. A prime example of this is the biblical story of Saul, who was called the Apostle Paul and whose epistles were made into table books.[SB1]

We delete the things that prevent us from reaching our goal. Mostly they are feelings. Think of Hamlet, who begins to arrange his own space by erasing his feelings, he gets rid of all the hindering instincts that will get in the way of his main goal – revenge.

We erase all unpleasant memories, including those the remembering of which would make them less likely to happen again, because we know that no one cares about how difficult our lives have been. An example of this is the biblical story of Thomas of Manasseh.[SB2]

Furthermore, we also delete snapshots in which we do not like ourselves, where our flaws and blunders are visible, like in unprocessed photographs that have not yet been touched by the omnipotence of editing programs. At this time, we are very much like Joseph K by Kafka, who realizes that he has been arrested, that is, his personal development has been stopped, because he depends on other people's opinions and tries to please them, to live for them and not for himself. This is the manifestation of our authoritarian consciousness – to succumb to what is imposed on us and to erase the reality that requires us to make efforts to correct it.

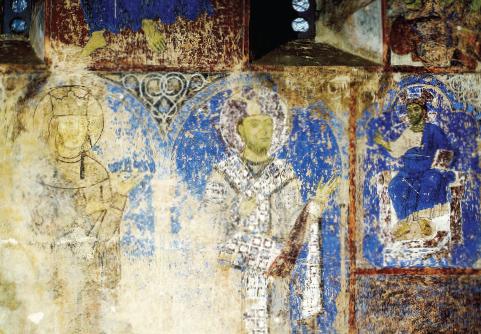

In ancient times, the delete system was adapted to myth. What could not be dealt with by human effort was preserved in a myth. This system worked for quite a long time and successfully, almost until the Baroque epoch, when the society had another social responsibility to the existing cultural context – that of the Renaissance crisis. And a radical modernization began in the epoch of Realism, when life was no longer a dream but reality, and the chance of its disappearance, of its erasure, was reduced to a minimum. Since then almost nothing has changed, except for the forms of perception of reality. Growing social pressures and political cataclysms had become an everyday occurrence, so the delete system was in full swing.

This is well seen in postcolonial literature, where writing has taken over the correlation of memory and history in order to bring public consciousness out of a traumatic, stagnant state. It believed that erased, or deformed, memory affected, distorted reality and contributed to the degradation of social perception, as well as the personality. Faulkner for one devoted his entire oeuvre to the relationship between memory and reality. In his novels, the erased memory and, therefore, the identity of the characters are unable to perceive the reality of the present. Here, even Yoknapatawpha is a fictional city, the time is fictional because it doesn't really exist and is as old and ritualistic as Quentin's stopped watch (The Sound and the Fury). This is how personal deconstruction begins, which, according to Faulkner, can only be reconstructed by restoring memory.

From this viewpoint, Salman Rushdie's novels are absolutely outstanding. Here memory is seen as a means for bringing the marginal man out of his crisis situation, a man who has no uniform sense of the past with the existing society, and in order to adapt he begins erasing the historical past and replacing it with a new one.

But he is so strongly attached to his own invented history that it replaces his memory, and even more so, the mythology of his country. According to the writer, the synthesis of memory and history is the only solution for those people or nations who have had a long break with their past. Rushdie is unique in that he tries to change the general discourse of postcolonial literature, which has separated memory and history from each other, that is, divided them into archaic and personal fragments – that which is experienced by ancestors and that which draws on subjective experience – and is focused exclusively on subjective memory. Though Rushdie did also leave room for archaic memory in his novels.

And how have we as a society, more or less associated with the above processes at all times, acted? With a kind of cultural infantilism and civic nihilism, the only reason for this is that we have let into our zone of existence all those infected files that break the system, and we have deleted the protection program, now we are struggling to get out of this reality and are waiting for it to be fixed, and occasionally lightly touch the delete button, which insistently responds that it cannot be done.