Author : David Khvadagiani

On 10 February 1918, the first session of a representative body, the Transcaucasian Sejm, convened by the Transcaucasian Commissariat, was held in Tbilisi, in what is now the Opera House. The convocation of the Sejm was an important political act: it was the culmination of disagreements with Moscow after the Bolshevik coup in Russia in October 1917. The Transcaucasian Sejm legalised secession from Soviet Russia and paved the way for the creation of the Transcaucasian Independent Democratic Federative Republic, which was proclaimed later on 22 April 1918.

The Georgian Social-Democrats, the Armenian Dashnaktsutyun, the Azerbaijani Musavat, and other parties opposed to Bolshevik Russia had ambitious objectives against the backdrop of global events. They aimed to establish the Transcaucasian Democratic Federal Republic, with Tbilisi as its political center. For Tbilisi, left without an ally amid the ruins of the Ottoman and Russian empires, the integration of Transcaucasian countries into the United Republic and control of the Baku-Batumi highway were crucial factors. This strategic move aimed to draw the attention of powerful European states and secure a strong protector and ally.

However, the local Bolsheviks, a Moscow stronghold, did not sit idle. On the basis of a directive received from Moscow, they organised a large demonstration in Tbilisi’s Alexander Garden against the Transcaucasian Sejm, protesting against the secession of Transcaucasia from the Soviet Russia. The famous Bolshevik and “teacher of Stalin” Arakela Okuashvili wrote in his memoirs about this Bolshevik rally on 10 February: “On this day was the opening of the Menshevik Sejm. We gathered under the leadership of our committee from each district. Among us were; Filipe Makharadze, Seryozha Kavtaradze, Kamo’s sisters: Petrosyan Javaira, Arusiaka, Lusika, Sandukhti, iason Dzhorbenadze, Giorgi Chkheidze, Nestora Tsertsvadze,Stefane Shaumyan, Nikolai Kuznetsov, artillerist Petrenko (Navtlukh) Kivkutsani, Malakia Toroshelidze, Parmen Sabashvili, Iason Dzhorbenadze from the 3rd district came with his comrades, Anton Mgaloblishvili held the banner. Stefan Shaumyan and Nikolai Kuznetsov were in the former Armenian seminary, they had to come to the opening of the rally”. The Bolsheviks’ official pretext was the legalisation by the Transcaucasian Sejm of secession from Russia and the protest against the closure in the previous days of the Bolshevik publications “The Caucasian Worker” and “ The Struggle” by the government However, in reality, their plan mirrored the Russian model. Just as the previous year saw them successfully storm the Winter Palace in Petrograd to capture the government, they aimed to attack the former Viceroy’s palace and destroy the Transcaucasian Commissariat.

Filipe Makharadze at the opening of the memorial to the fallen Bolsheviks, 1922

Filipe Makharadze at the opening of the memorial to the fallen Bolsheviks, 1922

The Georgian Bolsheviks had once already failed in their plan to seize power when on 12 December 1917 the newly formed Guard disarmed the Bolshevik garrison of the Tbilisi arsenal. They were driven by a desire for revenge, but their plans were foiled again. A special detachment of the Transcaucasian Commissariat, commanded by Georgian officer Vlas Imnadze, opened fire on the Bolshevik rally and dispersed it by force. Arakela Okuashvili recalled: “... I turned my face towards the bell tower, one bullet hit me in the lapel of my coat, I managed to get out safely to the Treasury building, there was a fierce firefight, rifles and machine guns were firing. I turned round and saw Philip Makharadze running away. He had a hat in his hand, his coat was dusty. He must have fallen. I grabbed his hand and rushed him into the Zemel shop to Gabo Okoyev. We entered the back room of the shop from the courtyard. Filipe was given a chair, Gabo’s wife Satinika cleaned his coat. Filipe was very excited, calling out in Russian: “Eto k luchemo, eto k luchemo.” (meaning – this is for the better ).

Arakela Okuashvili

Arakela Okuashvili

At that time even Arakela Okuashvili did not understand what was meant by the first Bolshevik of Georgia – Makharadze, who after the Russian February Revolution of 1917 was brutally defeated by the leader of the Georgian Social Democrats, Noe Jordania, in a political discussion who also thwarted Makharadze’s efforts to bring the Russian “Bolshevik Revolution” to Georgia. But fact was, that day marked the onset of a continuous three-year struggle between Georgia and Russia.From the declaration of Georgia’s state independence on 26 May 1918 until 1921, the Bolsheviks, backed by the funding and support of Soviet Russia, orchestrated three uprisings against Georgia. These events were accompanied by assaults from the volunteer army of the “Second Russia,” participating in the Russian Civil War, as well as two full-scale invasions by the Soviet Red Army. The second intervention in 1921 proved fatal for Georgia, leading to 70 years of Soviet-Russian occupation and terror.

Before this tragic outcome, significant battles unfolded. In one such battle, the Georgian Bolsheviks were rightfully branded as “agents bribed with Moscow’s gold.”

The Bolshevik “Agrarian Terror” of 1918

On 3 March 1918, under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Russia recognised the Batumi district, Kars and Ardahan lands as the property of the Ottoman Empire, but the Transcaucasian Democratic Federal Republic and the Transcaucasian Sejm, convened on 10 February, did not accept these conditions. after which the Ottomans began to occupy the territories by force of arms.

The Ottomans were given an opportunity to take revenge for their defeat on the Caucasus front, which was met by duly mobilized Russian satellite Bolshevik forces in the Caucasus, who tried to implement a small model of the Leninist course in the Caucasus and turn the global “imperialist war” into a Bolshevik revolution.

From late 1917, the Bolsheviks contributed greatly to the collapse of the Transcaucasian front and, supported by a mass of Bolshevised soldiers, attempted for the first time to proclaim Soviet power in Tbilisi, although the Transcaucasian Commissariat and the Executive Committee of the Tbilisi Council of Workers’ and Soldiers were able to defend the city and the railway. The Tiflis Red Guard (later the People’s Guard) thwarted these coup plans by seizing the Arsenal and disarming its garrison.

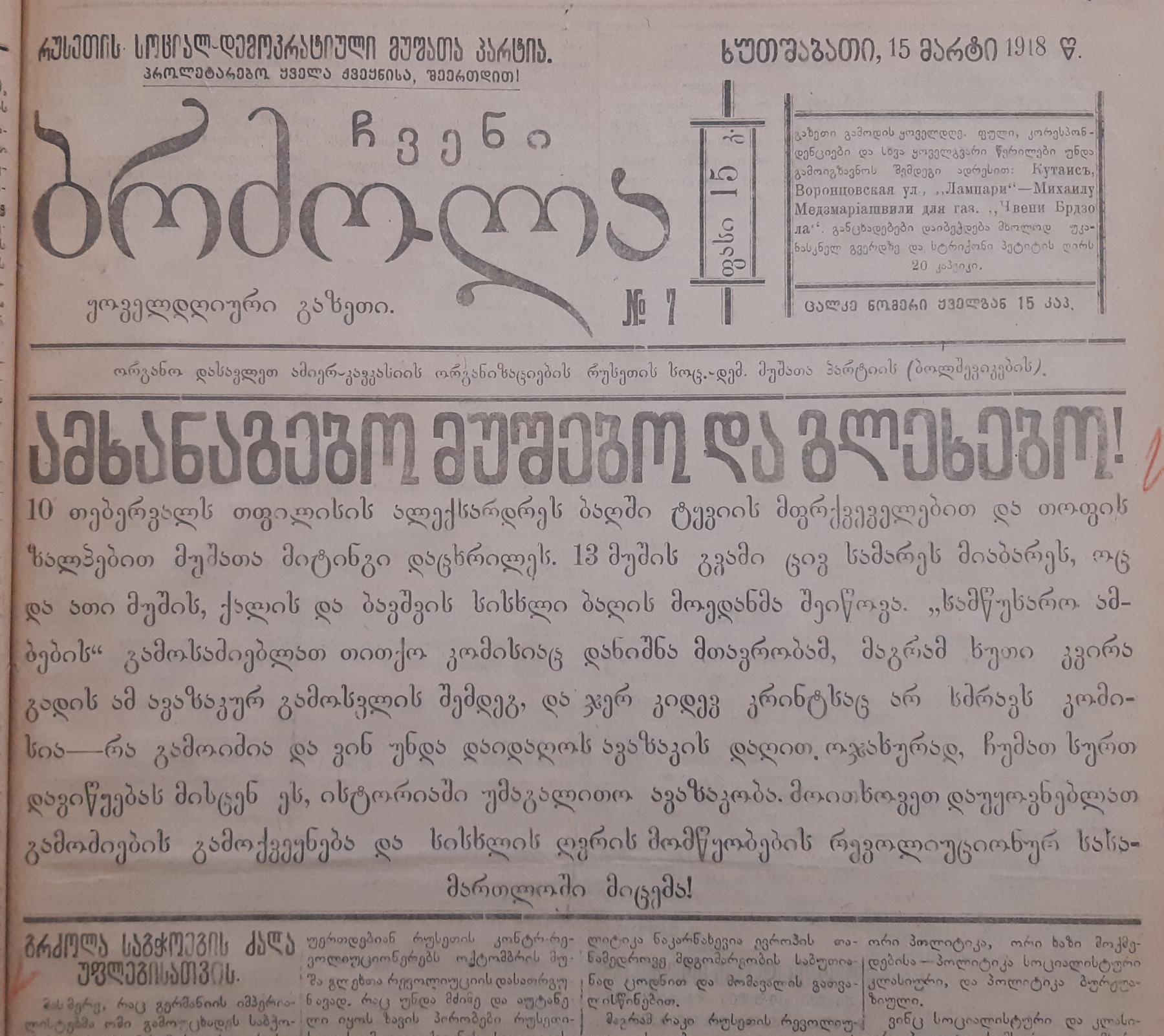

The newspaper “Our Struggle” March 15, 1918

The newspaper “Our Struggle” March 15, 1918

In the spring of 1918, the Bolsheviks stirred up a series of uprisings in Georgia. The uprisings were organised from the Kavkaz (Vladikavkaz), the main city of the “Soviet Republic of Terek” in the North Caucasus: Bolshevik uprisings broke out in Kakheti, the mountains of eastern Georgia and the mountainous part of Imereti. Alexander (Sasha) Gegechkor’s units were particularly active in the counties of Samegrelo and Racha-Lechkhumi, followed by the declaration of Soviet authority in Lechkhumi and the loss of the Transcaucasian government’s de facto control over the region.

On 26 March 1918 the Bolsheviks seized power in Sukhumi and proclaimed Soviet power in the whole district.

Events were particularly dramatic in the Dzhava and Tskhinvali districts of the Gori district, populated by Ossetians. Contemporaries assessed the armed uprisings that broke out there as “agrarian anarchy” and pointed out that the inclusion of a significant mass of the Ossetian peasantry in them was also conditioned by their difficult socio-historical background.

Artillery of the People’s Guard in Sochi, 1918

Artillery of the People’s Guard in Sochi, 1918

The resettled and landless Ossetian peasantry didn’t wait for the development of a new land reform after the revolution, as the majority of the peasantry in other regions did. Spontaneously and arbitrarily, they began seizing the lands and property of former landlords, and, in some cases, physically liquidating them. The brutality of the rebellious peasants, including former soldiers and deserters, was also influenced by the well-crafted agitation of the Bolsheviks. They conducted covert agitation among the peasantry, suggesting that “the Mensheviks and the Guard had sold out to the nobility and were planning to restore serfdom.”

The anarchy in Gori district (Mazra) presented a special threat to the Transcaucasian authorities, as it jeopardized the central railway line. The defense of Batumi would have become impossible if the group of deserters operating in Gori district, led by Isak Kharebov, a former lieutenant colonel of the Russian Imperial Army, had succeeded in taking over Tskhinvali and Gori. To address this, the Transcaucasian government had to reorganize the armed forces, albeit at the expense of weakening the Batumi District front. Guard commander Valiko Dzhugeli managed to defeat the rebels and restore order within a few days, but this was enough time for Batumi to fall without outside help.

On 1 April 1918 (April 14 in the new style), Batumi fell, and the Ottoman army gained control over Adjara. On 17 May 1918, the Guards occupied Sukhumi, and Valiko Dzhugeli triumphantly entered his hometown. Subsequently, the Georgian army, along with the Guards, successfully cleared the entire region of Abkhazia of Bolshevik forces.

Following Germany’s offer of protection and alliance, Georgia declared its state independence on 26 May 1918. With the support of the Georgian authorities and the People’s Guard, all pockets of rebellion were neutralized during the summer, initiating a process of stabilization in the country.

The 1919 Dream of a Russian “ Coup”

From the autumn of 1919, following the Bolsheviks’ success in the Russian Civil War, they resumed activities in Georgia. However, unlike the previous year, they no longer possessed ample resources to organize an uprising in the region. The self-government and land reforms implemented by the Georgian government, along with informational efforts, fostered loyalty to the republic among the rural population and mitigated the potential for a social upheaval. Additionally, the effective operations of military counterintelligence and the special division (security service) of the Interior Ministry further contributed to stabilizing the situation.

The Caucasian Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Russia changed tactics: this time the uprisings were not organised spontaneously, but involved surprise attacks and the establishment of control over the state administration, post and telegraph and other important facilities by well-organised groups in virtually all districts of Georgia and in the capital Tbilisi. They were also planning to arrest members of the government and, by neutralising them, to exert decisive influence on the Georgian armed forces, which would be virtually left without leadership.

Noe Ramishvili and Noe Zhordaniaა

Noe Ramishvili and Noe Zhordaniaა

Particular attention this time was paid to the capture of the Transcaucasian railway and the Tsipi tunnel, which would give a significant advantage to the organisers of the uprising. The committee sent the Georgian Bolshevik Ivan Dzhejelava to the district of Gori to lead the uprising. The plan was as follows: armed detachments were to occupy the town of Khashuri; Arsen Lomidze was to attack from the Ali side, Znaur Aidarov from the Khtsisi side, and Tate Buhrikidze from the Surami side.

The Bolshevik uprising of 1919, which was supposed to start on 7 November, was doomed to defeat: Georgian security services knew their plans in advance, and the Bolshevik, illegal military-revolutionary headquarters, in which a Georgian counter-intelligence officer was embedded, was detained by a special unit of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in the “Aurora” hotel on Vorontsov Square.

Among those arrested was the chairman of the so-called Garrison Military Council, Ilia Mgeladze (pseudonym “Korogli”). The center of the rebellion was liquidated , the RCP(B) of the Caucasus Regional Committee canceled the preparations, but due to the lack of information, rebellions still started in Kakheti, Guria, Abkhazia and Gori districts, although the units of the People’s Guard met the demonstrations prepared and had no problems in liquidating these hotbeds.

“The Republic of Georgia newspaper”, November 12, 1919.9

“The Republic of Georgia newspaper”, November 12, 1919.9

The failure of the November Uprising dealt a severe blow to the Bolsheviks. Soon after, the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia released a statement by the Minister of Internal Affairs, Noe Ramishvili, in which he detailed the Bolsheviks’ plans. In an interview with a British correspondent, Ramishvili also revealed that the Bolsheviks had brought 87 million manats from Soviet Russia, which they had spent on bribery and propaganda. However, he emphasized that the Georgian government had been aware of their plans from the beginning and had no difficulty neutralizing them.

After the liquidation of the uprising, the military field command sentenced to execution several Bolsheviks arrested in Guria, Gori district, and other places. According to the decision of the military field court, the Ossetian Bolshevik Znaur Aidarov, who had been imprisoned, was also shot (in 1938 the Soviet occupation authorities gave the name of Znaur Aidarov to the Kornisi district in Shida Kartli).

On 30 November 1919 counter-intelligence officers of the People’s Guard arrested Georgian Bolshevik leader Filipe Makharadze, disguised as a priest, on Kodjori Street in Tbilisi.

The Guards seized secret documents from Makharadze, wherein it became known how the Bolsheviks planned to seize state institutions in Tbilisi and other cities.

1920 - “Red Vendée.”

In 1920, at the instructions of Sergo Ordzhonikidze, head of the Caucasus Bureau of the Russian Communist Party, extensive preparations were undertaken in the Caucasus. In April, a “South Ossetian Partisan Brigade” was created from Ossetian militant Bolsheviks who had fled Georgia in previous years, and Razden Kozaev, an old Bolshevik, was appointed its political commissar. However, Kozaev had no time for work in the brigade, more important things were awaiting him. In May, the 2nd conference of the newly created South Ossetian organisation of the Communist Party of Georgia elected him a member of the district committee and brought him to Moscow to present the “Appeal of the workers of South Ossetia” to Vladimir Lenin. Kozaev was received by Lenin during the Second Congress of the Comintern in Moscow and was given the promise to help the “rebellious workers of South Ossetia”.

May 1920 was a difficult start for the countries of the Transcaucasus:

Soviet Russia took advantage of the conflict between the republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan. As most of the Azerbaijani army had been mobilised in Ganja and Karabakh against the Armenian army, it occupied Baku almost without a fight and continued its offensive directly towards Tbilisi. But this attack was not the result of inertia. Bolshevik combat units were already prepared to operate in the rear, both in Georgia and in Armenia, and immediately tried to seize power, which manifested itself in a Bolshevik uprising in the Kars district, an attempt to attack the military school in Tbilisi and to capture members of the government, but this operation also failed. Nikoloz Nizharadze, a counter-intelligence officer of the People’s Guard headquarters, uncovered and arrested a group of terrorists led by the Bolshevik Pavle Mardaleishvili.

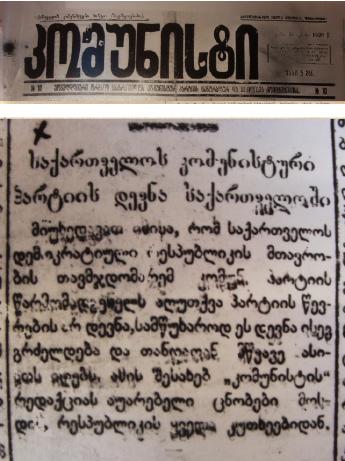

“The Communist” newspaper June 13, 1920

“The Communist” newspaper June 13, 1920

The plan was as follows: when the Red Army attacked Tbilisi, the Bolshevik terrorists, who had a secret base in the village of Maghlaki in Imereti, were to blow up the railway bridge at Rion station, thus cutting off supplies to the Georgian army and the People’s Guard. A similarly dangerous military situation was created in other parts of the country: the Georgian army and the People’s Guard had to repel the Red Army division in the east – from Piolio, Sadakhlo and the Red Bridge. A tense situation was also created in the Batumi region, from where the British were already withdrawing, and a covert battle was under way to recapture the region.

The Georgian authorities were aware of the British withdrawal plan and began moving military units from Ozurgeti as early as January, and from the end of April Georgian troops became more active in the Artvini and Khulo directions. On 2 May Georgian units occupied Artvini, but serious problems arose in the direction of Khulo. In the Batumi district, where the volunteer army had considerable influence, there was a strong Bolshevik underground and a pro-Ottoman and then pro-Turkish organisation, the Batumi Islamic Council, aka “Sedai Mileti”. Establishing control over the Batumi district by the Georgian government was not in the interests of either of them. This coincided with secret negotiations between Soviet Russia and Kemalist Turkey, and armed units of the “Sedai Mileti”, linked to the Bolshevik underground, put up serious resistance to the Georgian army on the Kobuleti and Khulo roads. Bolshevik terrorists Akakii Surguladze and Germane Dzhibladze, on the instructions of Sergo Gubelia (Medzmariashvili), head of the Batumi Bolshevik Committee’s combat groups, blew up the railway bridge over the Kintrishi River on 23 April to stop the Georgian army’s advance.

On 5 May 1920, the Red Army finally took up positions opposite the Georgian coastal forces near the Psou River. Military intelligence agents became active on the Abkhaz side. At a time when the Georgian Democratic Republic was under pressure from Soviet Russia, the authorities had information from the Georgian intelligence network in the North Caucasus about the invasion by Ossetian Bolshevik units that would again threaten the rear of Tbilisi and the main roads and railways of Georgia, which soon became a reality and the “South Ossetian Partisan Brigade” broke into the rear of the Georgian army and the People’s Guard in the direction of Java-Tskhinvali.

Ilia Mgeladze

Ilia Mgeladze

The commander-in-chief of the Georgian armed forces, Giorgi Kvinitadze, was forced to regroup his troops and send battalions of the People’s Guard from the eastern front in the direction of Tskhinvali. The beginning of anti-Soviet uprisings in Ganja in early May and in Zakatala district on 9 June gave him such an opportunity: in Zakatala district protests of Azerbaijani beys – Galadzhiev, Kardashev and Abasov – began with the support of agents of Georgian military intelligence, and according to unconfirmed information Georgian special services supported the Ganja uprising – it was controlled from the office of Noe Ramishvili. The Red Army command was forced to send significant units against the rebellious Azerbaijanis.

The underground struggle continued in the rear of the Georgian armed forces: on 6 June, Georgian counter-intelligence arrested the Bolshevik Sofia Pressman at Natanebi station, who was carrying a huge number of proclamations against the Georgian government and the British, printed on behalf of the Batumi Committee of the Russian Communist Party, from the editorial office of the newspaper “Communist” in Tiflis to Batumi. The proclamations consisted of two parts: one was directed against the Georgian government, accusing it of “intending to retake the Batumi region by force of arms”, the other against the “British imperialists”.

In June 1920, six battalions of the People’s Guard, artillery, and cavalry units completely cleared the Gori district of rebellious Ossetian Bolshevik units and averted the danger of a blockade of Tbilisi.

On 13 June 1920, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Georgian Democratic Republic closed the newly opened newspaper “Kommunist”, published on the basis of an agreement of 7 May 1920 “for the rebels of South Ossetia”, because of its support to the “right to self-determination” and proclamations printed for Batumi.

“The Devil’s Whip” newspaper #31, 1920

“The Devil’s Whip” newspaper #31, 1920

On 25 June Georgian Telegram Agency reported that a conspiracy against the Democratic Republic of Georgia was disclosed in Sukhumi and Gagra. The plot involved communists: Kukhaleishvili, Vigryanov, Svanidze, and others. The investigation found weapons, grenades, explosives, and military maps in their possession. Together with them, Georgian counter-intelligence arrested Bolshevik terrorists who had escaped from Batumi – Akakia Surguladze and Germane Dzhibladze, who had been serving their sentences before the Russian occupation in 1921.

Melkisedek Kedia and Platon Pachuliaია

Melkisedek Kedia and Platon Pachuliaია

In July 1920, the British left the Batumi district and handed Batumi over to Georgia. The Georgian army and the People’s Guard entered the city. Muhammad-bey Keskin-zade Kiknadze, commander-in-chief of the Ajarian army and leader of the Batumi Islamic Council, was secretly linked to the Georgian government. Although Keskin-zade held out hope for his allies, the Bolsheviks of the Batumi district, he did not resist the Georgian armed forces. He disbanded his army and moved to Khopa. After two years of fighting, Batumi was returned to the Georgian Democratic Republic.

The year 1921 – Dusk

Soviet Russia and its leader Vladimir Lenin, recognising the global political order of the new world based primarily on the principle of self-determination of nations, viewed the restoration of the Russian Empire in a new form with caution. His policy did not initially involve direct intervention and occupation. He preferred to take over targeted countries by organising internal coups and uprisings. From 1917 through 1920, all Russian attempts to overthrow the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia through rebellion and the expenditure of vast financial resources failed.

Valiko Dzhugeli

Valiko Dzhugeli

In early 1921, the de jure recognition of Georgia by the Supreme Council of the Allies and the arrival of the Georgian-friendly Aristide Briand in the French government was the precipitating factor for Soviet Russia to launch a direct intervention against Georgia, which Lenin did after the persistent persuasion of the Russian People’s Commissar for Nationalities, Joseph Stalin, and the head of the cabinet, Sergo Ordzhonikidze. Although Soviet propaganda for decades built a myth that in February 1921 in Georgia there was an uprising and overthrow of the “Menshevik government”, in fact it was a direct intervention and occupation. The famous historian Firuz Kazemzadeh in his book “The Struggle for Transcaucasia 1917-21” (published in the United States in the early 1950s) noted that the already weak Communist Party of Georgia disintegrated after the failed coup attempt in 1920 and “fell in spirit”. By 1921 it no longer had the resources to organise an uprising.

Giorgi Kvinitadze

Giorgi Kvinitadze

(The clearest example of this is the secret report of Filipe Makharadze, Chairman of the RevCom of Georgia (06.12.1921), which was published in full in Istanbul in 1922 by the émigré journal of the Social Democratic Party “Free Georgia” with the inscription: “Copy taken from the report kept in the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party”. This emphasised that, despite the military defeat, Georgian politicians and intelligence agents still had great influence and opportunities, even in terms of obtaining secret documents in Moscow. Filipe Makharadze wrote to Moscow:

Vlasa Imnadze

Vlasa Imnadze

“The following happened: when the Red Army offensive began, none of the party cells, imagine, not a single member of the party in Georgia knew anything about the purpose and intention of this offensive and did not even have any suspicions. Therefore, no preventive measures could be taken on the part of our organisations, as it was unknown that they were still alive. Obviously, this circumstance made it even easier for the Mensheviks, during the Red Army offensive, to settle the scores with our organisations left here and there and to capture not only Communists but also, to a greater or lesser extent, those who sympathised with them.” Thus the following took place:

● The entry of the Red Army into Georgia and the proclamation of Soviet power took on the character of an obvious invasion from outside, since no one inside at that time had thought of organising an uprising

● At the time of the proclamation of Soviet power in Georgia, not a single party cell was found, and even less a single party member who could have organised the establishment of power, so that in most cases this work could have been taken up by dubious or downright malicious elements.

People’s Guardsmen who died in the battle with the Bolsheviks in 1921

People’s Guardsmen who died in the battle with the Bolsheviks in 1921

In the 1920s and 1930s, as a result of party purges and mass repressions organised by Stalin, the majority of Bolsheviks who had fought selflessly in 1917-21 “for the establishment of Soviet power in Georgia” were liquidated.

For decades, the Soviet regime deliberately erased, wiped out, and falsified the most important events of Georgia’s twentieth-century political struggle. The erasure of Georgia’s “lost history” and political identity from the memory of generations is the most reliable tool of the aggressive Russian Empire to subjugate Georgian society.