Author : Editorial Team

The peaceful revolution that began as a kind of fairy tale ends in a nightmare of bombing, broadcast live on Georgian television on the night of August 7. Tanks and soldiers that I thought I had negotiated out of the country (a kind of revenge for the past that my family had to go through when they were forced to leave Georgia as a result of the Russian army’s invasion) invade and destroy the center of Georgia.

Here Zourabichvili touches on the issue of the withdrawal of Russian military bases from Georgia and presents it as her achievement. In fact, the decision to withdraw Russian bases from Georgia was taken at the OSCE Istanbul Summit in 1999. It was precisely this summit that was the decisive factor in this case. During the many years of international diplomatic efforts, Zourabichvili represented Georgia only at the final stage of the negotiations, when the decision had already been taken and the negotiating process was practically over. One could say that her tenure as minister simply coincided with the withdrawal of Russian military bases from Georgia.

The question that everyone has been concerned with ever since is twofold: Whose fault is it? Could this war have been avoided? The culprits and perpetrators are many. First and foremost, it is the lack of a clear line in relation to Russia. Is the lack of a clear line towards Russia.

The very phrase “Whose fault is it?” in military aggression by one state against another implies that the target of the attack may itself be guilty of provoking the aggressor and waging war. It is doubly difficult to put the question in this way when we are talking about tiny Georgia on the one hand and a nuclear superpower, the heir to the Evil empire, on the other. The use of military force by another country against a sovereign state for the purpose of violating its territorial integrity and changing its government is a flagrant violation of international law. In such circumstances, the legitimacy of the target to defend its sovereign territory cannot be questioned. However, it is not true that “everyone is concerned” about whose fault it is for the outbreak of war, as if there were any substantial ambiguity about this: The international community unanimously recognizes that Russia carried out aggression against Georgia in August 2008 and that Georgia was the victim of that aggression. The victim cannot be blamed for starting the war. There may have been some questions in certain circles about the provocation of the Georgian government, but this position was never universally shared. In subsequent years, this position of Zourabichvili and of her political partners was “refined” and formulated in a new cliché – “Georgia failed to prevent the war from the very start”. Representatives of Ivanishvili’s government tried to use this cliché with regard to Ukraine as well, but only a small percentage of domestic users remained listeners in the context of a global consensus.

From the very beginning, two lines clashed: confrontation and normalization. Behind this declared policy of confrontation and toughness with Moscow, there is also a trend that contradicts it: Selling the country’s resources to the main enemy, trying to make secret deals. This blurring of the lines has made the purpose, and therefore the consistency, of this policy unclear.

Here Zourabichvili contradicts herself. On the one hand, she claims that the line of confrontation has prevailed over the line of normalization, but on the other, with a conspiracy unbecoming of a formally high-ranking diplomat, she claims that the Georgian government has made secret deals with Russia and handed over the country’s resources to it. It is unclear what secret deals Zourabichvili is talking about, and she does not provide a single example. Furthermore, the two claims are incompatible. Moreover, this is a well-known Russian propaganda cliché that Zourabichvili repeats for a French-speaking audience. It should be noted that these two lines are developed simultaneously by Georgian Dream and Georgian-language Russian propaganda in Georgia.

In fact, immediately after coming to power, Saakashvili sought to establish good neighborly relations with Putin as a matter of priority. His first visit in his capacity as President was to Moscow. However, it soon became clear that Russia was not interested in equal relations with Georgia, the so-called normalization was only considered at a subordinate level, at the cost of concessions to Georgia’s national interests. It is also worth recalling an episode when, after the expulsion of Russia’s proxy Aslan Abashidze from the Ajaria ASSR and the restoration of the jurisdiction of the Georgian central authorities in Ajaria, Putin told Saakashvili directly and unequivocally: “Don’t expect any more gifts from us”. It is telling that Zourabichvili does not mention this key nuance at all.

From Normalization to Confrontation

The outlines of normalization will remain incomplete. On the second day of the Rose Revolution, Ivanov’s visit to Tbilisi, facilitating the overthrow of Shevardnadze and Moscow’s official blessing of the ongoing revolution, is a gesture of reconciliation. Saakashvili, for his part, extends a hand of reconciliation to neighboring Russia in his inaugural speech. This is accompanied by a period of détente in bilateral relations, which I have successfully used to advance bilateral negotiations. But this normalization is in fact accompanied by serious counter-maneuvers.

Already in the summer of 2004, this détente almost suffered a serious blow as a result of the first “missteps” in Georgian policy: The escalation of tensions in the Tskhinvali region and the deaths during the attack in August almost brought us back to the past, to the period of confrontation. But the situation is calming down and relations seem to be getting back on track.

When reading this passage, one gets the impression that Russia was ready for full normalization of relations with Georgia and that this was only prevented by the actions of the Saakashvili government. The fact that this was not the case was known to any reasonable Georgian of average intelligence, and should have been known to an experienced French diplomat who, because of Saakashvili’s serious staffing error, continued her mid-level diplomatic career as a minister in Georgia. From today’s perspective, the inappropriateness of these attitudes and expectations is even more obvious.

At the beginning of 2005, the line of confrontation with Russia appeared at the most inopportune moment. Just when the first rounds of negotiations had given us a chance to sound out the ground, the Georgian parliament passed a resolution demanding the withdrawal of the military bases I was negotiating, as an ultimatum, without any warning or reason. This challenge, thrown at Russia just as the talks are under way, could derail them. It is unacceptable in its form, because I have not even been consulted on this issue, as Foreign Minister and the main actor in these negotiations. Everything is happening independently of me, and one day the President will summon me to Parliament to persuade the Majority Leader, Maia Nadiradze, to drop this ultimatum.

I had not yet arrived at the parliament when I was contacted and told to call off my demarche: “There is no need, the decision of the parliamentary majority is so unshakable. The resolution would be passed on March 22, accompanied by a series of punitive threats ranging from water and electricity cuts to harsher measures in case of non-compliance.”

At the time, I must have been too naive to believe that the president did not have enough power to subdue the majority. Nadiradze was, and still is, very obedient. In other words, I was lied to. It is even more absurd to think that he needed my intervention to stop an initiative that he disagreed with. Simply put, it was not Nadiradze’s initiative, like many others that have taken place in this Parliament.

In addition to destroying me politically, this ultimatum could also destroy the negotiations I was conducting. In general, any ultimatum is a “killer” in negotiations, because the other side will see it as a preconceived malicious act. I was fortunate to be able to take advantage of [the Russian side’s] trust and mutual desire to succeed, which saved us from a deliberate failure. The maneuver was designed to damage both my personal success and the popularity it would have brought me, and the normalization of bilateral relations that the agreement would have brought. Be that as it may, this time the attempt failed and the process of negotiations survived.

The most striking thing about this passage is the inadequate, bordering on comical, self-assessment of a middle-ranking French diplomat who appeared in Georgian politics by chance, if you like, at Saakashvili’s personal whim. It was probably intended for the same French-speaking readers, because this text reads too ridiculously in Georgia. It should be remembered that she became Georgian Foreign Minister at the request of President Saakashvili to the French President. Before that, she was the Ambassador of France to Georgia. Now imagine: Rose Revolution, Adjara Revolution, the government still at the height of its popularity, Georgia’s historic attempt to free itself from Russian influence... and in this context Zourabichvili brings her personal popularity into the picture as a factor. For any observer with the slightest understanding of Georgian politics of that period, Zourabichvili’s self-aggrandizement is laughable. The passage only shows the subjectivity and inadequacy of the author, who seems to have represented herself more than the state in the matter of withdrawing bases.

At the same time, Zourabichvili claims that the agreement she reached could have normalized bilateral relations, which is absurd. In 1999, at the OSCE Istanbul Summit, Western diplomacy, at a time of Russia’s historic weakness and wielding great economic pressure, forced Russia to agree to the closure of such important military bases in Georgia, significantly weakening Russian influence over Georgia and the region as a whole. Putin’s inauguration and subsequent presidency soon became a symbol of anti-Western revanchism in Russia. So the fact that it turns out that Zourabichvili was warming up Russian-Georgian relations, which Saakashvili thwarted in order to prevent her personal popularity, is a mockery of the intelligent reader.

However, this maneuver will be repeated again. In October 2005, more important talks began at a completely different level, as this time it was a direct discussion between the United States and Russia on the separatist conflicts. The dialogue on South Ossetia begins between the Bush administration and Putin during their meeting at the UN General Assembly in Washington DC in early September. It will soon be followed by a meeting between Lavrov and Condoleezza Rice on the same subject. The question is whether it is possible to work with Russia to resolve the conflict, the key to which lies in the hands of the Kremlin. The aim is to bring the issue to the attention of the OSCE at the Ljubljana Summit in December. The Bush administration is determined to move forward, and the Russians are not shying away from discussion. That is already enormous progress. For our part, we are ready to see concrete results from these bilateral talks. In the summer, when the Russians begin to leave the Batumi base, the Russian Foreign Ministry suggests that the Georgian side begin consultations on the situation in the North Caucasus.

Here, most likely, the conversation refers to the so-called joint anti-terrorism center, the opening of which the Russians demanded in exchange for the withdrawal of military bases. This meant that in reality the bases would remain, but under a different name and this time with a legitimate status.

This is happening for the first time! At the end of August there was the CIS summit in Astana, where Putin and Saakashvili met. They agreed to meet again and discuss the possibility of an official visit to Georgia once the vintage was over. On the plane ride back to Tbilisi, I reassured the President that it was essential to make the invitation official. On my return, my office sent a draft letter to the State Chancellery, but it was never sent! Someone had blocked it and replaced it with another letter full of Russian mistakes and with Saakashvili’s facsimile. Everyone who saw it, including the Russian ambassador in Tbilisi, wondered if this was not a deliberate attempt to disrupt a visit that could have brought progress in bilateral relations.

Zourabichvili deliberately continues to paint a false picture of Russia’s full political readiness for normalization, which is manifested in its civilized, constructive approach and behavior. The impression is given that the West has also spared no effort in normalization and that the only obstacle in the way is the Georgian government and its incomprehensible motives. Zourabichvili again mocks the self-respecting reader by claiming that the discussion on resolving this conflict was decided at the level of Bush and Putin and that Saakashvili blew it. In reality, there have been constant high-level meetings on the so-called conflicts since 1993, but there has been no breakthrough in resolving them, for the simple reason that Russia has created, instigated, used and frozen these “conflicts” as leverage over Georgia and would never give up this leverage of its own volition. In fact, there is one big conflict between Russia and Georgia and it affects the present the situation and the future of Georgia itself.

Instead of the expected breakthrough, the situation is deteriorating very rapidly. In mid-October, in parallel with my dismissal, the Parliament will consider a resolution containing a new ultimatum. This time the target is the Russian peacekeeping forces, who are urged to leave Georgian territory, the Tskhinvali region by mid-February and Abkhazia by mid-July. If this demand is not met, Georgia will denounce the agreements that give them legal status and thus declare them an occupying force.

It is true that the Russian forces had a peacekeeping status, which they were given virtually by force as a result of Georgia’s defeat in the war, but at no time was there any real sense that these forces were truly a neutral, peaceful contingent. In fact, they were the guarantors of the maintenance of the harsh reality created by Russia’s use of force on the ground. It was not an impartial peacekeeping force, as is required by good practice. Zourabichvili simply ignores this key fact and continues to refer to the Russian forces as peacekeepers, deliberately misleading the reader once again.

This double ultimatum, unlike the one issued in February, achieves its goal: it stalls the negotiations between the Russians and the Americans. The same goes for the OSCE plans that were due to start in Ljubljana in December 2005. Georgian-Russian relations are deteriorating. Tbilisi has never left an international meeting without condemning the bias of the Russian peacekeepers in statements and communiqués. My attempt to negotiate a ceasefire in this war of communiqués was unsuccessful. After I left, the new minister, Gela Bezhuashvili, engaged in a real verbal escalation. There is no room for dialogue at the Ljubljana Summit. This opportunity was missed.

Zourabichvili once again claims that it is all Georgia’s fault and that even the defense of Georgia’s own interests within the diplomatic framework is unacceptable. This time it is the so-called war of communiqués. The author herself recounts how Saakashvili’s government tried to make the international community realize that the Russian military was not in fact a peacekeeping contingent and was acting against the Georgian state, while Zourabichvili, who as a minister was obliged to be at the forefront of this effort, made no attempt to do so. She spared no effort to hide the truth and save face for Russia.

In January 2006, an explosion in a gas pipeline between Russia and Georgia, which left the country without gas in the middle of winter, sparked a war of words between the two presidents. Saakashvili had no hesitation in accusing Putin, whom he calls a “Lilliputin”, of being behind the terrorist attack. Russia denies any involvement in the incident and accuses Georgia of trying to damage relations. Tensions are rising and Georgian exports are under the first Russian embargo. Who is really responsible? Both parties are.

This astonishing paragraph deserves special attention. Let’s follow the facts: (a) Russia’s use of energy as a weapon of political blackmail against its neighbors is a common method of Russian foreign policy under Putin; (b) in January 2006, during the coldest days of winter, three power lines exploded simultaneously on Russian territory near the border with Georgia, knocking out all three facilities and leaving Georgia without electricity and gas; and (c) the probability that this was an accident and not deliberate Russian sabotage against Georgia is next to zero.

The purpose of the sabotage was probably to change Georgia’s independent, pro-Western policy and to halt successful domestic reforms. In this situation, Salome Zourabichvili is not talking about Russia’s aims, the leverage of Georgia’s response and the form of Saakashvili’s response! She is concerned that, as it turns out, Georgia blamed Putin “without hesitation” for this barbaric, inhuman sabotage (but maybe these three explosions were really a coincidence, as the Russians said, right?). Zourabichvili also repeats the Russian propaganda narrative that Saakashvili allegedly called Putin a “Lilliputin” (there are no facts to support this, apart from Russian propaganda rumors allegedly spread by the author), which was one of the causes of the problems between the states. Zourabichvili concludes that Georgia is to blame for subversive acts committed against Georgia on Russian territory (“Who is really responsible? Both parties are”), thus completely diluting the responsibility of the aggressor and shifting the conversation from the perpetrator’s motive to the victim’s reaction... Isn’t this exactly what Russia wants?

After that, both sides continue to aggravate the situation: On the Georgian side, insults continue unabated, which is the weapon of the weak. From the Russian side, there is an enormous range of possibilities that are allowed by force (distribution of Russian passports to the residents of Abkhazia, numerous border crossings by official Russian delegations without Georgian visas, direct investments on the Abkhazian Riviera without the permission of the Georgian authorities), and all this in contradiction with international law and the commitments signed by the Russian side, by which it recognized the territorial integrity of Georgia. Russia begins to pursue a policy of “creeping annexation” of separatist territories.

That same summer, President Saakashvili gives the order to open fire on Russian ships that violate Georgian territorial waters. Russia condemns this “criminal order”, accusing Tbilisi of threatening civilians and highlights Georgia’s bellicose attitude.

Under the pretext of violations of sanitary norms, the Russian blockade extends to the import of wine and mineral water, dealing a serious blow to the Georgian economy. Defense Minister Okruashvili challenges the Russians in front of the cameras: He responds to accusations of wine falsification with an aggressive formula, “Our wine, even if it is mixed with feces, is still good enough for Russians!” Russian society reacts painfully, taking it as a national insult. For Georgians, the wine embargo touches not only the vital nerve of the economy but also patriotic strings: In Georgia, the grapevine is a symbol of nationality and religion. With this confrontation we take another step into the realm of irrationalism and emotion.

September 2006 marks the beginning of another new phase – the arrest of four Russian intelligence officers. These agents are arrested and extradited publicly, with the accompanying anti-Russian rhetoric, that is not usual procedure in the disclosure of such cases. Moscow responds by deporting four hundred Georgians brought into the country on cargo planes. This is the most blatant form of racist campaign supported by the official authorities, which takes the form of a “manhunt for Caucasians” in the streets of major Russian cities. Add to this the blockade of air routes, the abolition of visas, the embargo on all kinds of agricultural products and finally the recall of ambassadors.

Note that Zourabichvili presented all of Russia’s criminal actions as a response to Georgian provocations. However, let us not go too far, the arrested spies were involved in subversive, destructive and terrorist activities in Georgia (remember the terrorist attack in Gori that they organized).

It’s not a war yet, but we’re getting closer to it.

Not to be outdone, the Georgian Defense Minister makes a loud promise: “I will celebrate the first of January 2007 in Tskhinvali”, which everyone sees as a major political breakthrough. Georgia is no longer ruling out a military solution to the problem. All the more so as no one is contradicting the words of the Defense Minister.

Both sides are involved in the escalation, each playing its part and effectively putting the ball in the other’s court. And both benefit from it. The Russian people are grateful to Putin for giving free rein to racism, which until now has been latent and unexpressed. Anything that looks like teaching Georgia a good lesson increases Putin’s popularity. Saakashvili, for his part, is also playing on patriotic sentiment, fulfilling the expectations of citizens and winning the local elections of October 5, 2006, thanks in part to Russian spies. In this war of nerves, any means are acceptable. Two non-democratic regimes are using symmetrical means to awaken the sleeping demons of their populations in order to gain popularity. The year 2006 marks the end of hopes for progress in the conflicts. And also the first serious crack in the calendar of Georgia’s rapprochement with NATO and the European Union.

Here Zourabichvili acts as a cynical “expert” representing a third party. With her feigned distance and moral neutrality, she places the aggressor and the victim on an equal footing. This is Russia’s aim – to show that Georgia is guilty too, that Saakashvili’s Georgia (which many in the world regard as a beacon of democracy and an example of successful reform) is just as much a regime as Putin’s Russia. Zourabichvili deliberately discusses Russia’s fascist policy of persecuting Georgians on the basis of their ethnicity, and even if it is a populist but legitimate attempt by the sovereign government of Georgia to expose the secret services of an enemy country on an equal footing... but no Russian official’s words can be as credible and convincing to the outside world as the text of a formally “Georgian” politician. It is precisely this role that Zourabichvili plays.

In 2007, we are one step closer to open confrontation. Russia is reinforcing its policy of applying double standards and gradually gaining a foothold in conflict zones. The Olympic Committee’s acceptance of Sochi as a candidate city for the Olympic Games is a new challenge for Georgia. Massive investment in Abkhazia’s neighborhood could push it towards Russia. Russia is increasing its presence in the separatist territories.

In this confrontation, Russia is emboldened by the change in the balance of power: It feels that Georgia is weak because of the divisions that have arisen as a result of the revolution, that its social and economic crisis is being exacerbated by the political crisis. Russia is particularly sensitive to changes in the global balance of power: Georgia’s main ally, the United States of America, is weakened. This is no longer the triumphant America of 2004, but the America of 2007, bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, with a president whose approval ratings are falling and who is no longer a reliable protector. Russia, on the other hand, is more confident in its own strength, and the rise in the price of oil and natural resources is increasing its revenues and strengthening it.

According to Zourabichvili, Georgia weakened after the Rose Revolution, which is not true, it is a lie and is not backed up by figures. According to all the data, Georgia was making significant, measurable, internationally recognized progress. The economy was growing, law and order was being strengthened, Georgia was being ranked as a progressive reformer in international rankings, the country’s international recognition and image were growing, which was reflected in an increase in foreign direct investment, investments were being made in defense and security, which was making Georgia more secure, and the so-called disagreements that arose after the Rose Revolution did not weaken Georgia. In the early years, President Saakashvili enjoyed a very high level of trust, which, although weakened in 2007, was still high enough to maintain a stable socio-economic and political environment in the country. So Zourabichvili is lying when she says that Georgia has weakened after the revolution. It is also absurd to claim that the seemingly diminished role of the US has had a negative impact on Georgia’s importance to the West. In fact, the Bush administration’s foreign policy at the time gave Georgia a prominent place because it was a successful example of reform and democratic transformation in the region. Based on the foreign policy of the USA, in which the spread and promotion of democracy in the world was of key importance, the American support for Georgia in this period was historically high, which Georgia also used. It is significant that in this paragraph Zourabichvili refers to the US as a “protector”, another Russian propaganda cliché woven into the text.

Russia is tempted to take advantage of Georgia’s weakness, to make a show of force and intimidation at lower cost, to regain a foothold in the Caucasus that it could not bear to lose, and to avenge its humiliation. It is looking for an excuse, it is organizing provocations. It wishes to push Georgia into making a mistake. It will achieve this more easily than it could have hoped.

Zourabichvili claims that Russia has lost the Caucasus, which is unfortunately a lie. Russia never completely left the Caucasus, it had its own military representation in the region and occupied territories, which in 2008 though they did not have the status of “occupied territories”, they were in fact occupied. Zourabichvili tries to show that Russia needs a mistake on the Georgian side in order to return. But Russia had a significant military contingent in both Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region.

Saakashvili is ahead of expectations and is entering the game. The more the Georgian president feels his popularity waning, the more he is tempted to play on patriotic motives, to use military rhetoric and to make promises about the return of territories.

The more the Russian president senses the growth of his own strength and the weakness of his neighbors, Ukraine and Georgia, or their patron, America, and the division in the Western camp over the admission of these two countries to NATO, the more he is tempted to take advantage of this division and raise his voice.

Zourabichvili again uses a Russian propaganda cliché when she says that Ukraine and Georgia (meaning the governments that came to power as a result of the color revolutions) have “protectors” in the West.

This dynamic of escalation leads to conflict, and neither side is willing to stop. At the beginning of 2008, the framework is in place, the script is written, and this is the script of the announced war.

The option of maximum confrontation is supported by the idea that the strategy of tension helps to gain maximum support from the American allies and increases the strategic importance of Georgia. So why not follow this logic to the end and try to get the discreet Americans to take action to protect Georgia, which is in open conflict with Russia – why not put Washington in a situation where it will no longer be able to abandon its small and loyal ally? Wouldn’t it be better to take the risk of cutting out the tumor rather than engaging in futile and time-consuming negotiations that will exhaust the country? What is a better way than war to show Russia’s true face and aggressiveness and make Georgia look like a victim?

Faced with Russia’s consolidation of its positions, its constant seizure of territories and its provocations, Saakashvili is trying not to fall behind and not to disappoint his people’s expectations. He made the return of the territories his main electoral promise, vowing that he would not leave the government without restoring Georgia’s territorial integrity; he had to show his people that he could stand up to Russia and achieve success.

Instead of real victories, false achievements and lies feed the propaganda. But this will come at a price in the future...

For example, the police operation has made it possible to regain control of Kodori Valley near Abkhazia, which had been held by local Georgian armed gangs for 15 years. The Georgian authorities have not stopped trying to portray the restoration of control as an annexation of territory. To support this view, the high mountain valley is called Upper Abkhazia. In fact, this is a lie, since the valley in question never belonged to the Abkhazians and therefore could not be taken away from them.

This lie will come at a high price: During the war of August 2008, Abkhazian and Russian troops will enter Kodori Valley, taking Georgia at its word. If the Kodori valley is part of Abkhazia, then its return is legitimate!

This paragraph would have been shockingly incompetent even if it had been written by a first-year political science student in Greenland. Given that it is written by a senior, experienced French diplomat, the version of incompetence here is hard to believe. There is only one explanation – that this is being done deliberately, on purpose, to mislead the world community, to point the arrows at Georgia and to justify Russia’s war of conquest. It is a fact that Kodori Valley was included in the administrative borders of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, Georgia, much of which was controlled by the Russians and their separatist proxies after the 1992-1993 war. The claim that the reason the Russians seized the Kodori Gorge during the 2008 war and expelled the Georgians from it was just because it was called Upper Abkhazia is such a blatant lie that repeating it would make even the most brazen Russian propagandist blush. But not Salome Zourabichvili.

A different kind of manipulation is taking place in South Ossetia, known in Georgian as the Tskhinvali region. Saakashvili decided to create an alternative separatist government loyal to Tbilisi in order to defeat the separatist regime of the Moscow puppet Eduard Kokoiti. In a show of generosity, he gives this loyal government the capital (Kurta), the administration, the budget (several million dollars), the president (Dimitri Sanakoev) and the territory (the Liakhvi and Akhalgori valleys, populated mainly by Georgians and under Tbilisi’s control since the 1992 war). Saakashvili will even hold presidential elections in the part controlled by Tbilisi in order to give his separatists the legitimacy they need. Thus, in order to consolidate the scheme of two separatist regimes with two presidents, Saakashvili is establishing the name of South Ossetia and legitimizing for the time being the borders that Russia will recognize tomorrow as the borders of an independent Ossetia.

Rather than showing generosity, the appointment of Sanakoev was a political move by the Georgian government, the wisdom of which is debatable. But the main point here is that Zourabichvili is once again blaming Georgia for Russia’s illegal actions, as if Saakashvili’s domestic decisions caused the Russians to occupy the Akhalgori region during the 2008 war. In fact, Russia was guided by Russian and Soviet maps, which showed Akhalgori as part of the former South Ossetian Autonomous District, and as such, for them subject to occupation.

Attempts at secret negotiations with Moscow

Saakashvili knows that his popularity is waning. He is increasingly dependent on patriotic propaganda built around the return of lost territories. He expresses impatience with the hopelessly frozen process of conflict resolution and the excessive caution of American and European allies. Expectations of rapid progress towards NATO membership, which he seeks more for his own popularity than for strategic vision, are receding.

As Zourabichvili’s narrative style is rather chaotic, it is difficult to tell which period she is talking about in which paragraph. In the previous paragraphs, the author is talking about the situation before the war. If this paragraph also refers to the same period, then Zourabichvili is lying when she claims that expectations of rapid progress towards NATO membership were receding. In 2007-2008, Georgia’s integration into NATO was at its peak. The first disappointment came in April 2008, at the Bucharest summit, when Merkel blocked Georgia’s and Ukraine’s accession to NATO, though it was written in the declaration that Georgia and Ukraine would definitely become members of the Alliance at some point. It is also a lie to say that Saakashvili’s decision to join NATO was driven by domestic rather than strategic considerations. Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations took on a systematic form during the UNM’s rule.

The attempt to negotiate with Moscow is understandable. Moscow holds the key to resolving the conflicts and, indirectly, to power in Tbilisi. Especially since democracy is paralyzed. Saakashvili knows his Western partners too well not to know that his move towards autocracy will one day end with the harshest criticism of him. For the moment, is he not tempted to move closer to Russia, from which lessons in democracy are less expected? Publicly, such a rapprochement is unthinkable because the threat of Russia is needed to feed the populism in which the regime reigns. Therefore, if an agreement is to be reached, it will have to be a secret one.

According to Zourabichvili, Saakashvili knew that the West would react with criticism to the move towards autocracy, and so it was logical that Saakashvili would try to get closer to Russia, from which lessons on democracy were less expected. The only thing that could bring Saakashvili’s government closer to Russia was the issue of the reintegration of Abkhazia and Tskhinvali. But even in this case, Saakashvili’s attempts to negotiate with Russia came to an end when he realized that there was no point in negotiating with Russia. Zourabichvili’s thesis that the Georgian government is tending towards Russia is unsupported, speculative and, in the style of Russian propaganda, designed to confuse the reader. Even more incomprehensible is the conspiratorial assumption about possible secret negotiations, for which there is no evidence.

Shortly before the August conflict, Saakashvili recalled that during his first and longest meeting with Putin in 2004, which lasted three hours, Putin asked him to give him some time to “digest” the revolution in Adjara and then he would deal with the South Ossetian issue “in a year or two”! But only on one condition: Saakashvili should not try to speed things up.

If this is true, then we can assume that Putin perceived the 2004 incident as a blow to this secret deal. This, in turn, raises questions about the reliability of commitments made by the Russian side, especially secret ones.

It is telling that Zourabichvili gives a high degree of credibility to Putin’s alleged words, the source of which we do not even know and which have no basis whatsoever, and confidently offers us the version that Saakashvili allegedly “dumped Putin”.

How can we trust the secret agreement with Russia? Why should we, when we know the history of Russian-Georgian relations?

Zourabichvili continues the same line. Let’s remember that the fact of a secret agreement has not been proven by any evidence. Not even by a single speculative argument. This conspiratorial version is based only on her assumptions and the rumors she herself spreads. Nevertheless, Zourabichvili is already selling this rumor as fact and attacking the phantom that she herself has created.

And how can we believe that Russia, eager to restore its great power credentials, would be willing to agree to the terms of a confidential agreement that the world would perceive as its withdrawal from the Caucasus, where it has been retreating for decades? The Ganmukhuri episode in October 2007 provides some answers to these questions. President Saakashvili, accompanied by several armed men, personally confronted the Russian peacekeepers and “pushed them back”. It is possible that this symbolic retreat convinces the Georgian president that the partial withdrawal promised to him by the Russians is real. He is seduced.

In this paragraph, Zourabichvili’s conspiracy theory takes on a new tone. In fact, the version is completely speculative and lacks any factual basis, as it is clear that she has no information about the issues discussed behind closed doors during the meeting of the two presidents. It is completely unclear what Zourabichvili is relying on other than her own imagination to accuse Saakashvili of a secret deal with Putin, when such a deal is not backed up by any facts.

Internally, after the demonstrations of November 2007 and the crackdown of November 7, which culminated in the raid on the Imedi television station, a movement towards authoritarianism is gaining momentum. After the elections and the partial opening of the media under American pressure, Saakashvili knows that the clock is ticking on his “forced democratization”. The presidential and parliamentary elections have failed to resolve the crisis facing the country. In order to restore his image abroad and his popularity at home, as well as to recover the money spent on the elections, bought at the price of gold, there is only one solution: war. The number of incidents in Abkhazia has increased since the spring. But a categorical warning from the US administration, accompanied by a visit by Condoleezza Rice in July 2008, temporarily halted this drive. Such a clear warning poses an acute dilemma for the Georgian regime: US calls for caution, growing criticism of the lack of democracy, lack of progress in the conflict zones, delayed expectations of NATO membership at the December 2007 ministerial summit and the April 2008 Bucharest summit leave little room for consolidation and strengthening of domestic authorities.

What are the frequent incidents to which the author refers? What proof do we have that these incidents are staged by the Georgian side and not a Russian provocation? The statement without evidence is speculative and aims to provide readers with false information in order to deliberately mislead them. The assumption that Saakashvili needed the war repeats the Russian propaganda message to justify Russian aggression. It is not supported by any evidence and is not shared by any (!) serious researcher, diplomat, or politician.

The scales are beginning to tilt towards the northern neighbor, who holds several keys: economic development, as it is the only potential market in the near future and one of the main shareholders in the privatization of Georgian assets; conflict resolution; and finally, Tbilisi knows that it is a partner whose advice on democracy is not to be feared. These are genuine arguments for some in the Georgian government, who are beginning to seriously consider the Russian option.

It is difficult for the Western mind to imagine how Saakashvili and Putin could hate each other and at the same time the interests of the two leaders could coincide. However, such interests do exist: Saakashvili wants to return at least a small part of the territories and regain the trust of his population in order to strengthen his position again. And Putin is trying to force Saakashvili into a move that would ultimately cut off his path to NATO and deprive him of unconditional American support. For each of them this is about consolidating their own power.

At the very least, it provides a better understanding of what happened in August 2008. It is difficult for us to imagine that Saakashvili would have embarked on this adventure in defiance of a publicly expressed call from Washington, knowing that he could not count on American and European support, especially from the French president, whose sympathies for Georgia were weak because of the traditional pro-Russian sentiment in Paris.

Relying on your own military might against the Russians is unbelievable! There is not even one chance in a thousand. The Georgian army is incapable of defeating the Russian Armed Forces, despite considerable expenditure on armaments and despite the progress made thanks to the American “Train and Equip Program”. Despite all this, the Georgian army is still in its infancy, unable to stand up to its large northern neighbor. Nor can it count on its reservists, since these young men have had only two weeks’ training. And he can’t count on the effect of surprise. The fact is that the number of incidents in the conflict zones has increased since the beginning of the summer, and everyone’s attention is riveted on them. And while official Georgian rhetoric makes no secret of its military ambitions, the constant Russian air strikes and the large-scale “Caucasus” military exercise held on the Russian side of the border in July, involving hundreds of tanks and thousands of troops, show that Moscow will go to any length.

How can we assess the operation carried out when it is clear that it cannot count on the effect of superiority, nor on the effect of surprise, nor on the help of others, and that the power ratio is one to thirty? Either it is a suicidal operation, in which only an insane president could involve his country, or it is an operation designed to cover up something else, such as a secret deal.

And in this paragraph, Zourabichvili again puts all the responsibility for the outbreak of the war on Saakashvili, who, as if with rational, personal motivation, planned and carried out the whole series of actions that culminated with the 2008 war. She still talks about the “secret deal” she invented, which remains a myth because its existence has never been confirmed by her or by any other circumstances. She calls the government’s response to the aggression against Georgia a suicidal operation and uses the traditional Russian cliché that the country has an insane president (remember – the same rumor was spread about Zviad Gamsakhurdia). They have not changed the cliché – why should they, when it worked the first time and Georgians have a memory of no more than 2-3 years? While she puts all the responsibility for the August war on Georgia, she makes no mention of Russia’s responsibility. She does not mention the West’s recognition of Kosovo in early 2008, to which Putin promised a disproportionate response. For some reason, she does not mention Russia’s withdrawal from the CIS agreement, the demonstrative introduction of railway troops into Abkhazia, the shooting down of a Georgian drone by a Russian military aircraft, Russia’s rejection of all peace proposals (including Steinmeier’s initiative)... All this not only raises doubts and questions about the author’s good faith, but also contains the only obvious answer to these questions: Zourabichvili’s book serves Russian interests.

There are many indications in the official statements that this is the case. For example, Deputy Defense Minister Batu Kutelia admitted in an interview with Figaro: “We warned the Russian forces that we would see to illegal formations. They gave us the green light to intervene (...) We didn’t think the Russians would go that far”. Other Georgian officials admit that they “did not expect” such a reaction from Russia. It turns out that they were waiting for something else!

We can also recall the surprisingly conciliatory address of the Georgian president to the Russians in his televised speech on August 7, when he offered to guarantee the ceasefire he had announced. The head of state addressed the commander of the Russian peacekeepers, Kulakhmetov, forgetting that for months Georgia had been questioning the legitimacy of the peacekeepers and demanding their withdrawal.

There may have been some agreement that if the Georgian operation was quick and limited to Tskhinvali, the Russians would not have an immediate response. This theory is supported by the fact that the Ossetian government cleared Tskhinvali of a significant proportion of the civilian population a few days before the Georgian attack, as if to create space to persuade the Georgians to enter. It is also reported that the commander Kulakhmetov has received 4 million dollars for his “non-intervention”.

Again unconfirmed rumors, again in the style of the Russian secret services. Zourabichvili offers no proof of the deal. The fact that Kulakhmetov allegedly took 4 million dollars in exchange for non-interference is also just a rumor. It looks like such actions are a usual modus operandi for Zourabichvili. Let us recall the bombing of the Tsiteluban radar by Russia on August 6, 2007, during the visit of U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, about which Salome Zourabichvili, already in the opposition, said it could have been staged by Georgian special services to “blacken” Russia. In this way, she tried to portray the Russian threat to the US as a provocation by the Georgians. No one has made such a claim against Georgia since the days of General Grachev, who said during the 1992-1993 war in Abkhazia that the Georgians were painting their military aircraft in Russian colors and bombing their own positions in order to blame everything on Russia. In reality, the Kremlin could not come to terms with the reforms that had begun in Georgia, leading to the rapid modernization and westernization of the country’s economy.

Whether these agreements were public or secret, one thing is clear: Russia did not keep its word. It managed to trap the Georgian president, known for his impulsiveness.

The scenario is catastrophic. In three days, Georgia loses everything: It loses 10% of its territory instead of regaining it; it has hundreds of casualties that have yet to be fully counted; the prospect of NATO membership is closed for a long time; it pays an economic price that affects the driving sectors of its economy (tourism, transit, foreign investment). It is also losing international credibility: In particular, the Georgian president’s belated and erroneous version that Georgia was merely responding to Russian aggression does not stand up to factual scrutiny. This damages Saakashvili’s personal credibility and his image as an unblemished democrat.

Of course, Russia is loudly condemned and criticized for its transgressions, for its illegal and unjustified advances into Georgian territory, but the mistakes of the Georgians mitigate its guilt somewhat.

Again, Zourabichvili’s attempt to bolster Russia’s narrative and mitigate its guilt by blaming Georgia is clear: What mistakes is Zourabichvili talking about when she accuses Georgia as a whole of starting the war? It is inappropriate to talk about mistakes on the part of Georgia, because we would not have been able to avoid war under any circumstances, as the war in Ukraine has amply demonstrated. And even if there were mistakes on the part of Georgia, none of these mistakes could have mitigated the guilt of Russia for invading and occupying the sovereign territory of Georgia.

Exaggerated statements lead to a loss of credibility for both protagonists: The destruction is not as brutal as the Georgians first claimed, and the accusation of genocide by the Russians first diminishes and then disappears.

The Russians wanted to impress and intimidate. They demonstrated a war from the last century, designed to shock the post-Soviet population, with tanks and an archaic scenario that they did not want at all, instead of the modern type of war, which consists of destroying the strategic and economic centers of a country. The Russians were careful not to target anything important except military facilities: Neither the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline, nor the main presidential residence in Shavnabad, nor the East-West railway and highway, nor Tbilisi’s civil airport, which would continue to function throughout the war and allow international delegations to arrive unhindered. They leave the country’s economic apparatus untouched. Is it not because they already own much of it?

In this paragraph Zourabichvili offers us two lies and a propaganda rumor: First, that the Russians bombed only military targets. The bombed civilian houses in Gori, the blown up theatre in Senaki and a number of other civilian objects prove the opposite. The Russians bombed the houses of civilians and peaceful people. As for the fact that the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline, railway and road were not bombed, there are other reasons. Bombing Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan would mean going beyond the framework of the Georgian-Russian conflict and would also damage other actors, spoiling relations with whom it was not in the Kremlin’s interest. It was also illogical to bomb the highways. The Russians needed the highways for unimpeded movement. As a rule, the highways are damaged by those defending themselves in order to limit the enemy’s movement on their own territory. The same logic applies to the railways. The Russians would only have bombed it if the Georgian army had been using it effectively for its logistical tasks. The second lie is that the international delegations would arrive without any problems. Representatives of delegations from various countries claim that the Russians caused them significant problems in the air, which made their safe arrival to Tbilisi questionable. As for the propaganda rumor, it is again about the Russians taking over the Georgian economy, which is simply a lie. However, the fact that Salome Zourabichvili’s knowledge of economics doesn’t even reach the level of a schoolchild is something that many remember from her TV debate with Lado Gurgenidze before the 2008 elections, in which Zourabichvili, a candidate for the post of prime minister (!), said that she didn’t know or care about certain economic terms and indicators. Of course, if all you have to go on are rumors and your opponent’s propaganda clichés, what need is there for facts and figures?

In short, this war will be the result of a labyrinth of lies in which, in the end, no one knows who is betraying whom and who is lying to whom. We do not know what is more real – the confrontation, the deals made and rejected, or the lies about the return of territories. This war, which began with lies, is ending with the apotheosis of lies: Convincing our own people that we have won the war we have just lost. And on August 12, Tbilisi celebrates a “victory” on Freedom Square that leaves a bitter aftertaste.

In this situation of mutual responsibility between Moscow and Tbilisi, I do not want the emphasis on the responsibility of the Georgian side to be interpreted as an exemption from the responsibility of the Russian side. Quite the opposite. But what Russia has done, inexcusable as it is, was not unexpected or surprising for those who know its nature, its history and the history of Georgian-Russian relations. On the contrary, the fault of the Georgian side lies in the fact that the Georgian government, knowing that Moscow was trying to deceive it, did not resist the temptation until the end.

Although in this paragraph Zourabichvili tries to present herself as an objective and noble arbiter, she repeats the Russian propaganda message that, despite Russia’s actions, Georgia should not have succumbed to the provocation, as if it had any other choice. In the first sentence of the paragraph, Zourabichvili says that the Georgian side, along with Russia, is responsible for starting the war. Even in this paragraph she is inconsistent, because in the previous pages she argued that Saakashvili planned and unleashed the war because it was in his own interests.

There is a shared responsibility beyond these two actors. And first and foremost, it is the responsibility of the Bush administration. But not in giving the green light to any kind of military operation, as the Russians and some people close to Saakashvili have claimed. On the contrary, I witnessed repeated warnings that were the leitmotif of all the American visitors. Nor do I have any doubt that there has never been any encouragement or pressure on the Georgian authorities to consider military solutions to conflicts, or to hope that they would be supported. This has not prevented them from perceiving their own wishes for reality. Just as after the war, while hosting his Polish counterpart, Saakashvili dreamed that by provoking the Akhalgori incident he could involve Europe in protecting Georgian territory.

The actual responsibility of the Americans does not lie here. The responsibility is political: It lies in their silence about other misdeeds and failures immediately preceding the war. The lack of democracy is at the heart of Georgia’s chaos. The democratic regime would not go to war: The decision of the President on August 7 would have become the subject of discussion, it would have been published in the press, questions would have been asked in the parliament, obstacles would have been created. In the absence of a democratic system of checks and balances, no one dared protesting against this personal decision. No meeting of the Security Council, no discussion in the parliamentary committee. It is an isolated and total power (authority) that decides on issues of war and peace, conducts negotiations and is accountable to no one. That’s exactly what the Americans should have prevented since they were engaged in the promotion of democracy in Georgia.

There is also a functional weakness of the American system: How is it that despite an embassy with several hundred personnel in the country, military advisers under the Train and Equip Program, a USAID hired consultant close to the president (Daniel Kunin), despite frequent visits by Matthew Bryza, no one raised the alarm when the military was mobilized, when the presidential address was broadcast? Why did no one denounce the military budget, which was about a third higher than in 2007? Why hasn’t Washington used its influence to more clearly curb the military ambitions that have become increasingly apparent over the past two years? We are dealing with a systemic error, caused by negligence (when one foresees consequences and does nothing to prevent them) and weakness, when it chose to support individuals rather than the country’s institutions. The Americans seek stability more than they seek democracy. Democracy and stability have paid a price.

In this paragraph Zourabichvili says that the increase in the defense budget was an indication that Saakashvili’s government was going to start a war with Russia, but the increase in the defense budget only indicates that the government was trying to increase its defense capabilities. What is very important in this passage is that here Zourabichvili is repeating and elaborating the main messages of Russian propaganda. She portrays Georgia’s main strategic ally as complicit in the war. At the same time, in order to belittle the US state and security system, she presents it as incompetent, failing to recognize the true intentions of their ally. Finally, the author is traditionally inconsistent when she claims that the Americans saw no danger of war, while a few paragraphs above Zourabichvili speaks of a series of warnings from the Americans, which she says she witnessed personally. What this is – getting lost in her own lies, incompetence or acting in the interests of the enemy – the reader can determine for themself.

The European and international institutions, including the OSCE, the Council of Europe, the European Parliament and the ODIHR, which failed to speak out and recognized the elections as democratic enough for Georgia, also bear their share of responsibility. The suspension of Georgia before the second round of the presidential elections is also a missed opportunity to avoid war. If President Saakashvili had been elected in a democratically conducted second round, he would not have been the same president, nor would he have participated in the reckless gambling that his illegitimate victory rendered inevitable.

In this paragraph, Zourabichvili undermines the reputation of international democratic institutions (which, in light of the 10-year rule of Georgian Dream, is no longer really surprising) and casts doubt on their objectivity (which suspiciously coincides with the consistent policy and rhetoric of Putin’s Russia on the same issue). Zourabichvili still blames everyone, except Russia.

The Americans clearly wanted to pardon their protégé. The surprising silence of President Bush during the first three days also explains the Russian advance towards the capital. The Russian plan to mislead Tbilisi and then use force to teach Saakashvili a lesson, certainly did not go beyond asserting control over Tskhinvali in the name of the peacekeeping mission. However, as the red light was not switched on by the Americans as a sign of prohibition, the Russian war machine, happily engaged in its favorite pastime, had no reason to stop its advance towards the capital.

Europe once again stood up to the challenge and acted swiftly, combining adherence to principle and conciliation. Sarkozy showed flexibility and firmness, and the results were achieved largely thanks to him. Europe’s entry into Georgia not only marks the end of the offensive, but also delivers a real blow to Russia’s ambitions to regain the zone of exclusive influence in the Caucasus. Some have criticized the agreement for being ambiguous on some issues... The negotiations could not prevent a war, eliminate its immediate consequences, or regain lost territories. They saved the main thing: Georgia and its independence. The rest needs to be done.

Here Zourabichvili is trying to distance the US and Europe from each other, presenting the US as an incompetent partner in the adventure and putting Europe in a better position, thus trying to bring dissonance to Euro-Atlantic unity. At the same time, it is unclear if the US showed mercy to its protégé, as the author describes it. Then by what logic did it not help him to avoid war, moreover – “turned on the green light” for the Russian offensive? Furthermore, what is the explanation for Moscow stopping and not advancing towards the capital after Bush’s call? Finally, and here it is important to emphasize that Zourabichvili still talks about the responsibility of everyone except Russia, whose responsibility she mentions once or twice and in a casual manner. But nowhere does she refer to this state as an aggressor and occupant. A whole page is devoted to the responsibility of the USA and democratic institutions, and a whole chapter to the responsibility of the Saakashvili government. There is virtually no mention of Russia’s responsibility.

However, the idea of a deal with Russia, or rather the idea of division, has not gone anywhere. It appears again, this time in connection with Abkhazia, and implies division of the territory according to the Cyprus model. A division that would have given Georgia the southern part with the Gali district, so to speak, leaving the northern part to the Abkhazians. Saakashvili would later confirm that he had indeed sent a letter to his Russian counterpart in which he hinted at such a solution.

Trying to make a deal with Moscow is just beating the air. It is a last-ditch attempt to find a way out of the situation. There is a widespread belief among Georgians that Russian soldiers are corrupt and can be bribed. We will not win the war with Russia, but maybe we can negotiate the limitation of the conflict with them through a deal to which both protagonists will agree: Georgia will get the territories and the Russian side will benefit from the fact that the prospect of Georgia joining NATO will be reduced to zero and its ties with the West will be severed (territories returned to Georgia, NATO membership prospects reduced to zero, and ties with the West severed for the Russian side).

Fourteen years have passed since the publication of this book. In 2014 and again in 2022, Russia launched unprovoked and unjustified attacks on sovereign Ukraine. After open military aggression, Russia was recognized as an aggressor attacking neighboring states because of their Western vector and Euro-Atlantic aspirations. The Russian president has been recognized as a war criminal and Putin’s regime has been condemned as terrorist by many countries. All doubts that the then Georgian government was responsible for the August war have been dispelled. Instead, it has been proven that Russia was the aggressor, that it planned and started the war, that Georgia was defending itself against an illegitimate aggression in order to protect the freedom and independence of the state. There is no evidence of a secret deal between Putin and the then Georgian authorities even now 14 years after the book was published. Moreover, even under the conditions of the Georgian Dream government, not a single international document mentions anything about Zourabichvili’s accusations of a secret deal between the Georgian government and Putin and the disregard of national interests. The results and facts show the opposite. They show that Zourabichvili deliberately lied and acted against the interests of the Georgian state.

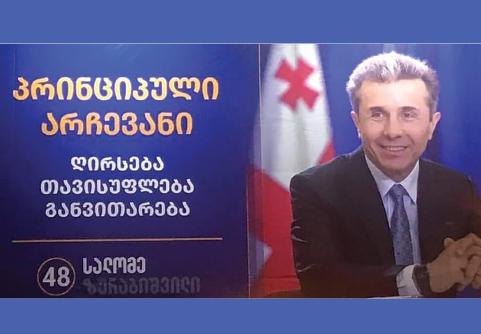

Today, Salome Zourabichvili is the president of Georgia. Formally, she ran as an independent candidate, but after her defeat in the first round of the 2018 presidential elections, the oligarch Ivanishvili showed his cards and declared that Salome Zourabichvili was his “principled candidate” for the presidency. In line with this choice, the special operation, called the second round of the 2018 presidential elections, was carried out with a full mobilization of state, administrative, financial, criminal and other resources. The OSCE/ODIHR international observer mission assessed these elections as “free but unfair”.

Translation by Davit Natroshvili